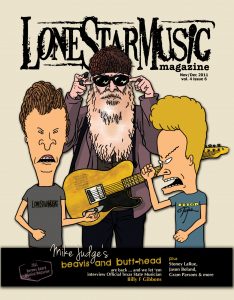

By Richard Skanse

(Nov/Dec 2011/Vol. 4 – Issue 6)

In the 2006 Mike Judge film Idiocracy, ordinary average guy and cryogenics guinea pig Joe Bauers (Luke Wilson) wakes up 500 years in the future to find himself the smartest man alive in an alarmingly stupid world. Alarming, that is, because as outlandishly over the top as Judge took the satire, there were aspects of his vision of America in 2505 that looked a lot more familiar and feasible than the gleaming utopia of say, Star Trek. No matter how far it’s set in the future, the Austin-based writer/director’s third feature film was less a work of science fiction than a scathingly funny commentary on modern society’s dangerous trajectory towards a dumb and dumber new world. Honestly, are we even 50 years away from hit TV shows like Ow! My Balls! and politicians flaunting their corporate sponsorships as shamelessly as NASCAR drivers?

If that seems a stretch, consider this: It’s the fall of 2011, and Judge’s two most famous caricatures of habitual imbecility, Beavis and Butt-head, are back on the air after a 14-year hibernation of their own — and they’re no longer the biggest idiots on MTV. Compared to the likes of Snooki and the rest of the Jersey Shore gang, the moronic cartoon duo might as well be the McLaughlin Group.

Or something like that.

“This is like a family tree, if like, your family was made of whores,” observes Butt-head in a clip from one of the new episodes in which the pair watches the Jersey Shore girls map out a “hook-up” chart on a blackboard. “If they like, did this chart long enough, they could find out where Herpes began.”

Go on, admit it: Whether you loved or hated these two incorrigible bungholes during their mid-90s heyday, you’ve missed them – even though they kinda sorta never went away. Bill and Ted and Wayne and Garth all had their 15 minutes of fame back in the day, but Beavis and Butt-head plopped their skinny short-pants-wearing-asses down in the middle of the Clinton decade and stayed, leaving an indelible impression on American pop culture even long after Judge put the original MTV series (which also spawned the hit ’96 movie, Beavis and Butt-head Do America) on ice in 1997 to pursue other projects. King of the Hill, the Texas-centric animated series he co-created with Simpsons veteran producer/writer Greg Daniels, ran for 13 critically lauded seasons on Fox, and his first two post-Beavis feature films, 1999’s Office Space and Idiocracy, have found an estimable level of cult-hit status that belies their modest returns at the box office. (His latest film, 2009’s Extract, isn’t quite there yet, but give it time.) But there’s just something about those two melon-headed losers that first put Judge on the map that’s always kept them near and dear to his heart.

“I’m really proud of Office Space and King of the Hill,” he says over coffee in East Austin in early October, “but I guess Beavis and Butt-head, when I go back to it, it’s the kind of stuff that can make you laugh over and over again. I don’t know … it’s hard for me to talk about my own stuff, but it just kind of feels good to me.”

Judge fans Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the creators of South Park, once likened Beavis and Butt-head to the blues — an analogy that says as much about the show’s legacy as part of the primal heritage of modern animation as it does the almost trance-like effect one can feel after watching several episodes in a row. Like a 12-bar blues song married to the right mood or beer buzz, Beavis and Butt-head just seems to flow in a way that can be absolutely hypnotic. Judge, who played bass guitar in blues bands in California and Dallas before his first MTV deal came along, nods in agreement. “I’d like to think it is like the blues, in that it always stays the same, and yet it somehow seems to work on different levels. Or it’s one of those things like the Three Stooges or Cheech and Chong or The Beverly Hillbillies, which I can watch over and over again and never get tired of. For me, the Beverly Hillbillies is like putting on a warm pair of Hush Puppies; it’s just comforting knowing that those characters are so solid, they’re never going to change.”

And neither, it seems, will Beavis and Butt-head. Sans the convenience of a time machine or cryogenic freezer, they really should be in their 30s by now — if not long dead courtesy of natural selection. But even though the new series (which debuted Oct. 27) casts them as model morons of 2011, draining brain cells soaking up hours of not only Jersey Shore but equally craptastic MTV reality show fare like Teen Mom, 16 and Pregnant and Cuff’d (along with UFC matches and ShakeWeight commercials), they’re still the same hapless 14 or 15 year-olds they were throughout the ’90s.

“Anytime a show has tried to age the characters … well, they don’t hardly ever do it, I don’t think,” Judge says. “There is one episode where Beavis and Butt-head are old, but I mean really old — they’re in a nursing home. And I did like doing that and might do more of it. For some reason, I can imagine them the way they are now and I can imagine them really old, but I have a hard time picturing them in the in-between.”

I suggest that a middle-aged Beavis or Butt-head would probably be a lot like one of his characters in Idiocracy, the Ow! My Balls! and Masturbation Channel-loving mouth breather played by actor Dax Shepard. “Oh yeah, Frito,” Judge acknowledges with a chuckle (most everyone in Idiocracy is named after a consumer brand). “Actually, that’s true …” Except that in the ass-backwards future of a world gone apocalyptically stupid, the hopelessly illiterate Frito happens to be a practicing attorney, while back in the 21st century, dim-witted teenagers Beavis and Butt-head are still mostly relegated to pulling half-assed shifts at Burger World.

Judge does give them a crack at working tech support in one of the new episodes, though. That was one of the many ideas he jotted down over the last 14 years, because the characters apparently never stopped knocking around in his thoughts, their infectiously inane laughter sometimes ringing in his head like a subliminal soundtrack to everyday life.

“Occasionally, I’ll see or think of something, and think, that’d be a good place to put Beavis and Butt-head,” he says. “Like that particular episode came from just, you know, I’m on the phone with tech support, it’s driving me crazy, and I start thinking how funny it would be to call tech support and get one of these assholes on the line.

“There’s a lot of stuff like that,” he admits. “So I guess in a way they have been in my subconscious all along — probablybefore I even came up with the first version of the show.”

***

IMAGINE THERE’S NO BUTT-HEAD …

Judge says he always figured Beavis and Butt-head would return in some form or fashion. Even before the new series was green lit and moved into production, he’d revisited the characters for a handful of special one-off appearances, including cameos on MTV’s Video Music Awards and a promo he put together for the launch of his last film, Extract (an underrated gem of a comedy which starred Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis, a pre-Bridesmaids-fame Kristen Wig and even a disarmingly funny Ben Affleck.) And given MTV’s obvious longstanding interest in the franchise, the prospect of a Beavis revival was really more a matter when rather than if.

But suppose those two “assholes,” as Judge so affectionately refers to them, never got a chance to rear their ugly heads in the first place. Or, suppose 1992’s “Frog Baseball,” the infamous amphibian-whacking Beavis and Butt-head short that Judge self-produced and submitted to MTV’s edgy showcase for independent animation, Liquid Television, had been a strike out instead of a surprise home run? Revisit the 2:53 minute cartoon on YouTube or on the DVD release Beavis and Butt-head: The Mike Judge Collection, Vol. 3, and you really don’t have to be a PETA prude to marvel at how that launched a pop culture juggernaut — let alone how it sprang from the same creative mind that would later give the world the Hills, arguably one of the most realistic and relatable families in TV history. On the evolutionary chart of Judge’s career, “Frog Baseball” is to King of the Hill (or even Beavis and Butt-head Do America and Idiocracy) as primordial pond scum is to Albert Einstein.

Regardless … had “Frog Baseball” landed in MTV’s reject pile instead of on the air, perhaps Judge (with or without Beavis and Butt-head) might have still gone on to somehow find his place in the world of animation, TV and film. Or maybe he would have just scrapped that particular dream for good and pursued a different life path altogether. Worst case scenario, he could have fallen back on his physics degree from UC San Diego, settling for a life of cubicle or factory-confined tedium — something right out of Office Space or Extract. Or, more happily, he might have just continued to play the blues.

“I’d always played music, and was actually doing that full time for about five years before Beavis and Butt-head started,” he says. By that point, he’d already tried and burned out on the 9-to-5 white-collar track. “I had an engineering job after I got my degree. I actually had one for about a year, another one for about three months, and then another one for six weeks. The second one was particularly bad. That’s when I realized, ‘I don’t think I can do this for the rest of my life.’

“The thing is, if you work in a more manual labor job, you can at least daydream,” he continues. “But if you have an engineering job, or even worse, if it’s a tedious office, alphabetizing thing, it occupies your brain for however many hours of day. In school, I’d think, ‘I’ll graduate, get an engineering job, and do fun stuff — music or whatever — in my spare time.’ Which I did for awhile. But when you’re working an engineering job where it occupies your brain the whole time, and you’re there for 10 or more hours a day, always staying late, it just drains you. So I knew I had to find something else.”

For Judge, music seemed the most viable and immediate alternative. While growing up in Albuquerque, N.M., he picked up trombone in the fifth grade and stuck with it long enough to make all-state symphony. By his sophomore year in high school he’d switched to bass guitar, and joined his older brother in a band called Universal Joint. “They weren’t very good, but we played a couple of things like dances and stuff,” Judge says. But he went on to play in the UC San Diego jazz band, and graduated to regular club gigs holding down the low end in a sweaty three-piece outfit called the Blonde Bruce Band.

“Blonde Bruce was this guy named Bruce Thorpe who looked like a blonde George Thorogood and played slide,” recalls Judge. “Bruce and the drummer were both 32 and I was like 22, but I auditioned for the gig and got it, and it paid really well and we played all the time in San Diego. The Navy guys loved him. I guess that’s what started me playing blues, even though I kind of wanted to play more rock ’n’ roll and country stuff.”

Not that he didn’t appreciate the blues. The soundtrack to Judge’s youth in New Mexico was equal parts classic rock and outlaw country, the later largely courtesy of the time he spent around Indian reservations with his father, an archeologist. “The Navajo stations out there would play a lot of tribal stuff, and then you’d hear, ‘[speaking in faux Indian gibberish] … Waylon Jennings!’” he says. “So I heard a lot of Willie and Waylon, and then I was all into AC/DC and that kind of stuff when I was that age. But then when I was 19, I saw that movie where David Carradine played Woody Guthrie [1976’s Bound for Glory], which was the start of me getting really into Woody Guthrie. It was a good way to get into music, because that Woody Guthrie thing is what got me back into things like Hank Williams and then the blues. It went back to the roots.”

After college and his stint with the Blonde Bruce Band in San Diego, Judge played with blues harpist Mark Hummel during a nine-month stay in the Bay Area before finally moving to Texas, his home for most of the last two decades, in 1988. He landed in Dallas, which conveniently featured a branch for the company his then-wife worked for, proximity to his father (who was then teaching at SMU), and a sweet and steady gig with Anson Funderburgh and the Rockets. After about a year with the Rockets (which featured Mississippi harp legend Sam Myers at the time), Judge eventually hooked up with another Dallas blues star, singing drummer Doyle Bramhall, of “Life By the Drop” fame.

For the record, these were not chump pick-up gigs. Judge was playing with the cream of the modern Texas blues crop, building an admirable resume that likely could have kept him in work on the scene for as long as he had a mind to. He still does play occasionally, though usually only when friends like honky-tonkers Dale Watson or the Derailers spot him in the crowd and reel him up onstage at the Continental Club or Broken Spoke. “Man, he’s great,” affirms Derailers (and former Watson) drummer Scott Matthews. “If he wasn’t in animation, he could play with anybody else he wanted to — he’s that good of a player.”

But back when music was Judge’s full-time job, his mind found time to start daydreaming again.

“I always wanted to do claymation,” he says. “My sophomore year in high school, I worked all summer at this drug store, and I saved up — it wasn’t much money, but I was either going to buy an electric bass or a movie camera. I ended up choosing the bass. I wanted to get the camera to start doing claymation stuff, but I realized it wasn’t just the cost of getting the camera, but also film and processing and projector, and I realized it just wasn’t going to happen because I didn’t have enough money for all of it.”

In lieu of clay and camera, he took to pencil and paper. Sporadically. “The mood would strike me every once in a while to draw stuff, and I’d always try to draw stuff that I thought would make people laugh – like in college, I’d draw teachers, things like that,” he says. “But I didn’t take a lot of pride in it. I tried to do panel cartoons, but the stuff just wasn’t that good because I’m actually not that great at drawing. Even now, I’m still not great at like, if I’m supposed to draw a car or buildings or mountains — I never learned the proper way to do all that. I never learned the proper way to draw anything, really.”

What he did develop a knack for, though, was animation — making even his crudest sketches move and come to life. “A lot of people think animating is tedious, but to me that’s way more interesting than illustrating,” Judge says. “Once I started doing that, I got pretty good at it.”

By the time he moved to Dallas, Judge had become enough of a animation buff to regularly attend film festivals devoted to the medium, including one called the “Animation Celebration” showcasing shorts and films from all over the world. The fact that one of the featured animators happened to be a local artist made a particularly profound impact on him.

“They had some of this guy’s drawings and a little blurb on him in the lobby, and I thought, ‘There’s a guy who does this right here in the town where I live,’” Judge recalls. “And then I realized, ‘I don’t have to buy a camera to do this — I can probably rent one.’ So the next day I got the Yellow Pages out, started calling, and went to the library and got a book on animation. It just became my obsession. I was still playing music at the time, but I just decided I was going to make an animated film, just to try it.”

“Frog Baseball,” his fourth short, would be unleashed on the world soon after, but first out of the the gate was “Office Space,” a 90-second introduction to Milton, the stapler-obsessed, mumbling desk jockey/door mat later brought to life by actor Stephen Root in the 1999 movie of the same name. The whole cartoon, which eventually found its way to network TV as a digital short on Saturday Night Live, was little more than the long-suffering Milton sitting behind his desk and grumbling meekly but almost incoherently about his job, his perfectly synced lips the only real movement apart from a brief interruption by his boss, Lumberg, who pops in to steal Milton’s stapler. Whether in spite of or because of its disarming simplicity, it still holds up as one of the funniest things Judge has ever done.

But it was Beavis and Butt-head, not Milton Waddams, that launched Judge’s animation and film career in earnest. MTV jumped on “Frog Baseball” almost immediately, offering Judge his own series — a nightly series. It all hit Judge about as hard as, well, a frog baseball bat.

“The animated shorts I did were literally homemade cartoons,” he explains. “It would take me like, six to eight weeks to do two minutes. My ex-wife helped me paint the cells, but other than that it was just me, doing every single drawing, all the voices, the music, the sound effects, the whole deal …” And MTV wanted 65 of those bad boys, ASAP.

The request came with a budget to hire a writing and production staff, along with an animation team, but it was still a Herculean task. And it seemed to only get harder when the show took off.

“As big as the show got, weirdly enough, it always seemed like we were understaffed,” Judge says. “And it always seemed like an impossible schedule, because the show was on every day. From the beginning, we just worked so hard — 16-hour days — and we did as many as 70 episodes or more in one year. There wasn’t ever any season hiatus, either; it was always like, as many as we could possibly do the whole five years that it was on.”

Obviously, his new schedule wasn’t going to allow any time for playing Texas blues. “I was actually still playing with Doyle until right before I moved to New York for Beavis,” says Judge, who moved with his wife and infant daughter to the Big Apple in January ’93. “In the beginning, MTV would fly me to New York when we were starting pre-production on the show, and I’d fly back to Texas later in the week to play a show with Doyle down in Austin or San Antonio or wherever on the weekend. And I kept playing with him until right up to around Halloween of ’92, which was when I finally said I can’t do this anymore.”

Beavis and Butt-head scored good ratings right from the start and wasn’t too long in hitting its perfect comic stride, but Judge is quick to note that not every episode was up to snuff. “I always knew in my head who the characters were and what I wanted the show to be, and it didn’t always work,” he says. “There were a lot of problems when the show was starting, but we had just moved to New York, my wife had quit her job and we had a 1-year-old, and I didn’t really have a contract yet. I mean, I’d sold MTV the characters, and I was getting some money advanced, but I had just heard about [Ren and Stimpy creator] John Kricfalusi getting fired from his own show at Nickelodeon, and I just thought, that could easily happen to me. I didn’t want to screw things up, because this was my only shot at having any kind of career doing this. So what happened was, I would write as many of the episodes as I could, but they had promo writers writing some of them, and there’d be these episodes where it’d be like, ‘Uh, OK, I guess we’ll record this,’ because I just didn’t want to be the ‘difficult guy.’ But some of them were just really bad — horrible episodes that I wish didn’t exist, but they’re out there.

“I tried to make them as funny as I could,” he continues, “but what I ended up doing was spending a lot of time on the ones that I thought were good, and just letting the other ones go. I still think the first couple of seasons are pretty spotty, but then I started to learn the game and realize that they don’t know what they’re doing — and I’m running the show.”

***

BACK TO TEXAS

In August of ’94, Judge and his family left New York and moved back to Texas — this time to Austin. After a somewhat shaky start, the production of Beavis and Butt-head was starting to run at least a little bit smoother, and Judge had enough of a handle on the process to realize he could do his work just as effectively, if not more so, on his own turf.

“It was actually easier to run the show from down here,” he says. “We still had a crew of maybe 40 people working in New York, and we had video conferencing and they’d fly people down for video records and stuff, but I could take the story boards and fax my orders back to New York, and not have people stop me in the hallway all the time. I just work a lot better from here. I was really homesick when I lived in New York.”

Judge was already in his mid-20s the first time he moved to Texas in 1988, but something about the state just clicked with him. He’s certainly lived in Austin long enough now for it to feel like home, but he developed a soft spot for the Big D during his years there, too. “I know everybody hates Dallas,” he laughs, “but I actually liked it. It’s an easy place to live, it was inexpensive, I loved it.”

And Texas has played a key role in his work ever since. Both Office Space and Idiocracy were filmed here (Office Space in Austin and Las Colinas, and Idiocracy in Austin, Pflugerville, Round Rock and San Marcos), and even Beavis and Butt-head Do America was partially set in the Lone Star State — albeit somewhat unintentionally.

“I always wanted it to just be in a nondescript town, some place with nothing to do,” he says of Beavis and Butt-head’s hometown, Highland. “I was thinking more like somewhere in New Mexico than Texas, maybe Albuquerque or Clovis. As the show went on I started to drop more and more little Texas things in there, but I still didn’t want name the town or state. But when we did the movie, what happened was, when you’re looking at the initial layouts, the license plates were just squares. But when the colors starting coming back from Korea, they were Texas license plates. So I went, ‘OK, I guess it’s in Texas now.’ Which is fine — but I really wanted it to be more generic and surreal.”

There was certainly no mistaking where King of the Hill was set, though. Judge admits that the fictional town of Arlen may have conveniently floated around the San Antonio/Houston/Dallas triangle a bit (“depending on like, if they were all going to Mexico for the day or something like that”), but every detail of the show was Texas to the proverbial T — from Peggy Hill’s mangled Gringo Spanish to the Tom Landry Middle School and right down to the Whataburgers. In a sly nod to East Austin, one episode late in the series even found Arlen’s “Little Mexico” neighborhood overrun with obnoxious hipsters. (“They put salmon in the fish tacos, Hank! Salmon! They’re ruining everything!”)

“I think a lot of what I’ve done is a reaction to what’s out there — and by that I mean, finding something that somebody else hasn’t already done,” Judge says when asked about the significance of Texas to King of the Hill and much of his other work. “Things are a little different now, but for a long time it just seemed like everything on TV was in New York or L.A. If somebody was a tough guy, they’d always have that tough guy, Brooklyn accent. But where I grew up, it was always 70 or 80 percent Chicano. But whenever I’d see a Mexican on TV, they’d sound Puerto Rican, or like Al Pacino in Scarface; nobody talked like what they really talked like around me. So on the rare occasions when I would see those details done right in a movie or a TV show, I always really appreciated it. I’d be impressed that somebody out there in the TV ivory tower could actually relate to something that I could relate to.”

King of the Hill featured a stellar cast of voice actors, including Kathy Najimy (Peggy), Stephen Root (Bill Dauterive), the late Brittany Murphy (Luanne Platter) and even, in later episodes, Tom Petty (as Luanne’s white-trash soul mate, Lucky). Judge himself voiced both Hank Hill and his mumble-jawed neighbor Boomhauer.

“When I was doing Beavis and Butt-head, there was this guy who left this really deranged voicemail — he thought the name of the show was ‘Porky’s Butthole,’” Judge explains with a laugh. “‘I’m callin’-upta-talkabout-why-y’all-keeba-playing-that-Porky’s-Butthole-ebbe-five-minutes … ebbe-time I come home, it’s Porky’s-friggin’-ol-Butthole …’ It went on for like two minutes before he just trailed off and hung up. I still have the tape. I’d originally meant to use the character for Beavis and Butt-head — just this guy yelling incomprehensible obscenities. I actually recorded it, but ended up cutting it.”

For Hank, Judge basically recycled the same voice he’d used for Tom Anderson, Beavis and Butt-head’s beleaguered old neighbor — and a fair amount of inspiration from some of his own neighbors right after he first moved to Texas.

“When I was pitching the show, one of the stories I’d tell was, there was this storm that had come through, and it blew a piece off of this wooden fence I had,” he says. “And I saw one of my neighbors looking at it, and he came over and was like, [Hank voice] ‘Well, you’re going to have to take the whole thing out.’ And then like three other guys came over, going, ‘I’ll go get my wheelbarrow …’ Before long, they’d knocked the entire fence down, and they’re in there digging and I’m trying to help out, but finally I just went back inside. And my wife was like, ‘What’s going on out there?’ I hadn’t even had my coffee yet, and they’re out there fixing the fence. I went back out, they’ve already got string going across, another guy got some concrete out of his garage, and another actually had a fence post. And the first guy — he was kind of like the alpha bubba or whatever — goes, ‘Well, you’ve just got to put the pailings on now …’ So I go and buy pailings, and I come back and start to put the first one on, and the guy walks over again, going, ‘Uh, you’re gonna need different kinda nails for that …’”

It’s a real trip hearing Judge channel Hank in person. During our interview, not once does he “do” Beavis or Butt-head — not even so much as a stray ‘uh … huh-huh-huh.’ But those are just cartoon characters. Hank Hill — animated or not — was real. Over the course of King of the Hill’s run, he evolved from alpha bubba caricature into one of the most true-to-life characters on TV. Texas Monthly went so far as to rank him as the greatest TV Texan in history — and they got it right (sorry, J.R.).

“Yeah, that was real nice,” he says. “From the get-go, I think one of my main jobs was keeping that show real like that. Because you get a bunch of writers working together, and there’s always this tendency to push things in this direction that’s just not … sometimes it’s a little easier to make everyone more ridiculous. But I like to think I kept it grounded. And it also helped with me doing the voice of Hank. We had such great people working on that, but I think I was able to set the tone partly just through playing that character. I appreciate stuff that’s surreal and crazy, but King of the Hill was not that type of show.”

Was. The show enjoyed a marathon run — especially by FOX standards, where only The Simpsons live forever — but the network finally pulled the plug in 2010 after 13 seasons. Judge talks about the show with genuine fondness and pride, but he doesn’t really see it ever returning. And he’s OK with that. “Never say never I guess, but that’s a hard show to do, all the way around,” he says. “There was actually a time when I had wanted to quit, but then decided to go another year. And then there was a time when they cancelled it, said we were done, and then they brought it back. So when they cancelled it this time … I was fine with it. I really wasn’t sure I wanted to do another season.”

Along with King of the Hill and Extract producer John Altschuler and David Krinsky, Judge co-created another animated sitcom, The Goode Family, which lasted for one season on ABC in 2009. “That one was mostly John’s baby,” he says. “I really just did a voice and some drawings. It didn’t really seem to work. Some of it did, but it flew under everybody’s radar.”

Then again, so did most of his movies — but only in theaters. The high-concept but low-budget Idiocracy, which Judge calls the toughest experience he’s ever undertaken in filmmaking, was given such a limited, half-assed release by 20th Century Fox that it didn’t even have a chance to bomb at the box office; it played in only 130 theaters nationwide and fizzled like a wet firecracker. But like Office Space before it, it’s found a remarkable second life on video. “Idiocracy took a long time to catch on, but I’d say that, once in a blue moon when I get recognized, that’s probably the top thing people talk to me about now days. At one point Comedy Central was even talking about doing it as an animated show. But I don’t want to do that.”

He may have no interest in going back to the Idiocracy’s dystopian future, but Beavis and Butt-head’s idiotic past was another matter entirely.

“I actually did feel that Beavis and Butt-head had run its course after the movie,” he says. “I remember Richard Linklater saying that after the Monkees movie, that that was like the cap, the end of the series, and I was kind of thinking of it in the same way. And I wanted to go on and do other things, so I never did regret stopping when we did. But I think I always thought that someday, in some form another …”

All MTV had to do was wait. And occasionally give him a poke.“ Every couple of years, they would ask about maybe doing another Beavis movie,” Judge says. “And I’d think about it and just started writing down a lot of ideas over the years. But I realized a lot of that stuff was actually kind of better for a TV show than for a movie. So when then they brought up the idea of doing the show again, it all just kind of clicked. Something about it just seemed right.”

Once he committed to the project — which he notes with pride is now called Mike Judge’s Beavis and Butt-head (instead of MTV’s) — Judge found that it still fit as comfortable as a well-worn concert T-shirt. I ask if getting back into character required any method acting preparation: a little glue sniffing, maybe — or at the very least, watching a lot of bad TV?

“Yeah — I fried my brain out a little,” he says with a laugh. He admits it took him a little practice to master the voices again, but he’s got them both down pat. “I kept recording stuff and listening back to it all the time, and I eventually got it to where I feel like you can now play the new ones and the old ones back to back, and it sounds the same. That’s another reason I wanted to do this now, because I think if I waited until I was 60, my voice would sound different. But right now it still sounds right.”

At the moment though, I can barely hear Judge’s voice at all. As an interview subject, he’s forthcoming, funny and thoughtful, but he’s a soft talker by nature — kind of a Milton, really — and the constant din of yattering twentysomethings in the crowded coffee shop hasn’t helped matters. And just now, some dumbass behind the counter has thrown on a Metallica album.

Judge doesn’t even seem to notice at first, and only acknowledges it with a nod and a quiet chuckle when I point it out to him. Somewhere not too deep inside his head, though, his little Beavis is surely going apeshit.

RELATED:

Tres Hombres: A very special LoneStarMusic interview with Billy F. Gibbons by Beavis and Butt-head

Seen on the Hill: A roll call of King of the Hill‘s musical cameos

How can I get a copy of this edition?

Hi Rochelle. You can order our Mike Judge issue of Lone Star Music Magazine here: https://www.lonestarmusic.com/index.php?file=mer-merchdetail&id=1905.

[…] 5. LSM Cover Story: Mike Judge’s Beavis and Butt-head | Lone … […]