By Richard Skanse

(LSM June/July 2010/vol. 3 – issue 4)

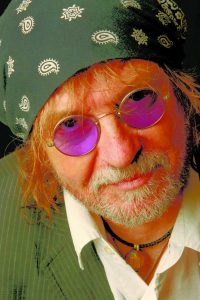

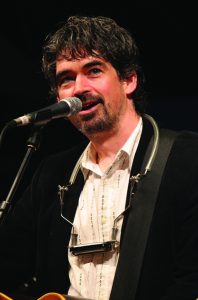

Ray Wylie Hubbard

“I don’t know if you knew this, but I used to drink. And there’s this story — I can’t remember this, but I can’t deny it, either — that I came out to play a solo gig at Kerrville one year, and I walked out onstage and never played a song. I think I was going through, oh, I don’t know, just a whole bunch of stuff. But I would start a song and then I would just start talking. Just some weird story or other, and then I’d start another song, and tell another story. And apparently I was really funny, but I never finished a single song. And finally I just went, ‘Eh, never mind,’ and walked off — and still got the mandatory Kerrville standing ovation! Like I said, I can’t remember this so you’d have to ask Dalis or Rod about it, but the story is that I got a standing ovation while I was in a black out.

I think I played like the first 12 Kerrville Folk Festivals, but after that incident, I didn’t play Kerrville again for years. Later on, by the time I’d cleaned up my act, I saw Rod at some function and went over to make amends, wanting to apologize for my performance and to ask him what I could do to make it right. He said, ‘Well, you can come back and play Kerrville again.’ So I finally went back, after an eight-year absence — eight years of embarrassment.”

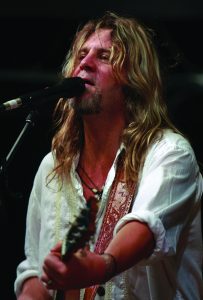

Walt Wilkins

“If you’ve been to the festival, you know that the speed limit in the parking lot is five miles-per-hour. There are signs everywhere that say ‘5’ on them. I was driving out there for the first time, and some hippie guy was yelling at me, ‘Slow it down, man!’ So I looked down and saw I was going six. I told that story on stage that night and people laughed so hard, because they know how true that was. They are very strict out there. It’s a well-oiled machine. But that really is an example of why it’s a such bulletproof, well-run festival. And it’s a dream to play. This will be my fifth year out there. They’re a tough crowd, and you’ve got to come with your ‘A’ game, but I love playing there. I got a standing ovation my first year and Rod Kennedy came onstage and gave me a hug. He’s since become one of my true champions.”

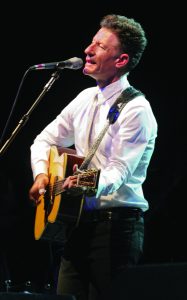

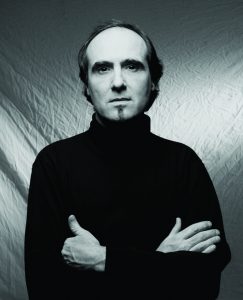

Lyle Lovett

“I can’t think of the exact moment I first heard about Kerrville, but it just seemed like there was a common awareness about it among everybody that played the songwriter and original music rooms around the state. It was mainly considered a great place to go listen to music, because the thought of maybe getting to play there eventually seemed like a far removed idea. But I went there to hear the music, and I camped, and I sent in a tape for the New Folk thing and all of that. 1980 was the year I got in. I didn’t end up winning, but I was thrilled to make the initial cut.

I remember one of the judges was Guy Clark, because he’s one of my heroes and I was really nervous to play for him. Being at the festival could be kind of intimidating in that way, just from being around so many people that you admire. When you’re young and you’re trying to do something, and like all of your heroes are in one spot, that’s a pretty awesome thing. So I was both intimidated and excited to be able to walk up to, you know, Gary P. Nunn or Butch Hancock or Ray Wylie Hubbard, and stick out my hand and say, ‘That was a great set last night.’ It was a thrilling thing. And I remember thinking how great it was that the performers would actually camp. There was a real sense of camaraderie, like they were all there enjoying what the festival had to offer, and it was just a nice thing to see.

After New Folk, I got invited back the next year to play in the afternoon, and later moved up to the main stage for the main part of the festival, which was a tremendous reinforcement that maybe I was supposed to be there, that I was supposed to think of myself as a songwriter and a performer, and that I maybe had a chance to really do it. I don’t think you ever lose that kind of insecurity when you’re a performer, but especially when you’re starting out, your wanting to do it is much stronger than your feeling that you’re allowed to do it. And getting to play such a great festival like the Kerrville Folk Festival really helps to validate that. It gives you confidence. And I not just getting booked there, but the whole experience of the festival itself. When you look across the campfire and see Nanci Griffith or Eric Taylor actually listening to one of your songs, that’s a pretty tremendous feeling.

And there’s so many other great, lasting memories, too. I mean, like getting to go down to the Medina River for a swim instead of the old shower. You get down there to take a swim, and you see some people that are naked, and you think, ‘Man … I like folk music!’ You never forget that stuff. It really was an education — in a lot of ways.”

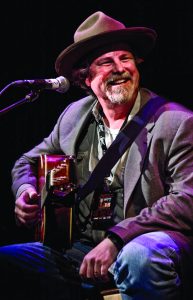

Guy Forsyth

“My favorite experiences out at Kerrville have been because of bad weather. There are times when it has rained out there and it rained really hard — like buckets and buckets and buckets pouring down. But the Threadgill Theater in the campground has a hard ceiling, so it’s a dry place, and you see the most magnificent display of humanity coming together there to make music without any sort of plan or government. It’s a totally organic thing with people just listening and going with what happens and paying attention. It’s not about, ‘here’s the audience’ and ‘here’s the artist,’ but rather ‘here is something we all do together.’ I think humans are at their best when they are making things to share with other people. Whether it’s making food, telling a story, or playing music in a way that’s just, ‘here is something that I love and I want to share.’”

Robert Earl Keen

“I was always one of those people who never won anything. I mean, anything, zero. I couldn’t even be the seventh caller and win a radio contest. So when I got on that New Folk stage and won, I remember being, not overwhelmed, but I just couldn’t believe that I won when I had never won anything before. By that point, I’d just decided that winning things was for other people. So it was a very, very exciting moment for me. And it was also kind of cool because, when I got up there to play, it was a really, really bright day, and real dry, and one of those dust devils came through the amphitheater right as I started playing. And I thought, ‘Wow, this is like some kind of sign or something.’ And watching that thing while I was playing my song just gave me this sort of calmness about everything.

The two songs I played were ‘Rollin’ By’ and ‘The Armadillo and the Jackyl.’ And one of the judges, I can’t remember who, said, ‘We almost cut you out because of that damn song about the armadillo, but you were really good.’ I said, ‘Thanks.’ But I never made any apologies about that song. I know the difference between a hit song and some little Ogden Nash poem, so I didn’t give a shit. But the fact is, it was all just really, really exciting. And it really did validate something for me, which I needed at the time. Because as soon as I could play music, secretly that’s what I wanted to do, but I wasn’t one of those people that started running around telling everybody that that’s what I wanted to do. Even after I graduated from school and went to Austin and started playing all those little joints and stuff, I still never told anybody. So I was always needing some kind of validation for myself, and for that I would say winning New Folk was a real benchmark in my checkered career. It finally got to be one day where somebody asked me, ‘What do you do?,’ and I said, ‘I do this.’”

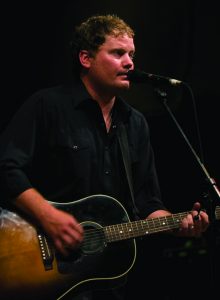

Slaid Cleaves

“In the spring of ’92, I was brand new in Austin. I’d spent five or six months dropping my little demo tape around all over town and being summarily rejected at every gig I tried to get. All I could ever get basically was open-mic slots. But I met Mark Viator and his girlfriend, Susan Maxey, that spring at the Austin Outhouse, and we became friends and Mark and I started playing together. Mark and Susan had met at Kerrville the year before, and they were just all pumped up about this wonderful festival. It was Mark who told me about the New Folk competition, so we made a demo of two songs that I’d written in Maine the previous year or so, ‘Life’s Other Side’ and ‘Willie of the Wind,’ and I submitted it. We were accepted, which was a good thing because I probably couldn’t have afforded to go to the festival at the time if not for that.

So, we all went out there, and Susan’s father, this old character named Jack Maxey — who I later wrote the song ‘New Year’s Day’ about — was sort of the patriarch of their little tribe, their camp. They called themselves ‘The Seekers of the Shade,’ and I was welcomed like long-lost kin by this wonderful, rag-tag extended family out there. And then Mark and I played at the contest, and we were winners, so I went from a zero to hero in 48 hours, whatever it was. My head was spinning, it all went so fast — it went from nobody knew who I was to, oh, New Folk winner this year! It was very, very sweet. I’ve had some great times out at Kerrville since then, but I’m still kind of living in the afterglow of that first year. It was just the perfect little introduction.”

Dana Cooper

“After playing the main stage one night, I went down to make the rounds at the campgrounds and ran into Keith and Ezra from Trout Fishing in America, who are friends of mine. We were just standing there, just off the path down by the meadow, and we started swapping songs. And by the time we finished a couple of songs, we had a couple of hundred people gathered around us. We did that for about 30 minutes, like an impromptu concert, having a great time and the audience was really into it.

After a while, this very enthusiastic young fellow stepped into the circle with his guitar, and asked if he could play a song. We said, ‘Sure.’ So we each did another song, and then said, ‘OK, your turn.’ And he started playing … ‘Margaritaville,’ by Jimmy Buffet.

I’ve never seen 200 people disperse so quickly! Before he even finished the song, I looked up, and everyone was gone and it was just him and me standing there. Everyone had left, just on the principle of the thing. And the poor guy, he had no clue; he was so excited, this was his moment, and he was really going to kill people, you know? I felt terrible for the guy, he really looked chagrined. I just said, ‘Well, you know, you gotta sing your own song.’ I think he learned a lesson from it, but that was a tough one!”

Randy Rogers

“I’ve only played Kerrville one other year [before this year]. It’s one of those festivals that I always really wanted to play while I was going to college in San Marcos and starting to play music in the area. I was never asked, but not for any other reason than I probably just wasn’t working hard enough to get there. So now that I’m finally getting to play it is a huge deal to me. I also got to be a part of Rod Kennedy’s 80th birthday party [at the Paramount Theater in Austin], which was a dream come true deal for me, too — getting to play with the Flatlanders, Marcia Ball and Robert Earl, and just being included in that group of people who have treated songs and songwriting as the main focus of their lives for all these years. To be recognized by Mr. Kennedy as someone who does that, too, just gives me a sense of pride and a sense that maybe I’m onto something.”

RELATED

LSM Cover Story: Kerrville Folk Festival

Camping Kerrville: After the main stage goes dark, the party’s just getting started

“Going Home”: Essay by 2008 Kerrville New Folk winner BettySoo

Campfire Girl: The story of Michelle Shocked’s Texas Campfire Takes

Go Fish: It just wouldn’t be a Kerrville Folk Festival without Trout Fishing in America

No Comment