By Richard Skanse

(LSM June/July 2010/vol. 3 – issue 4)

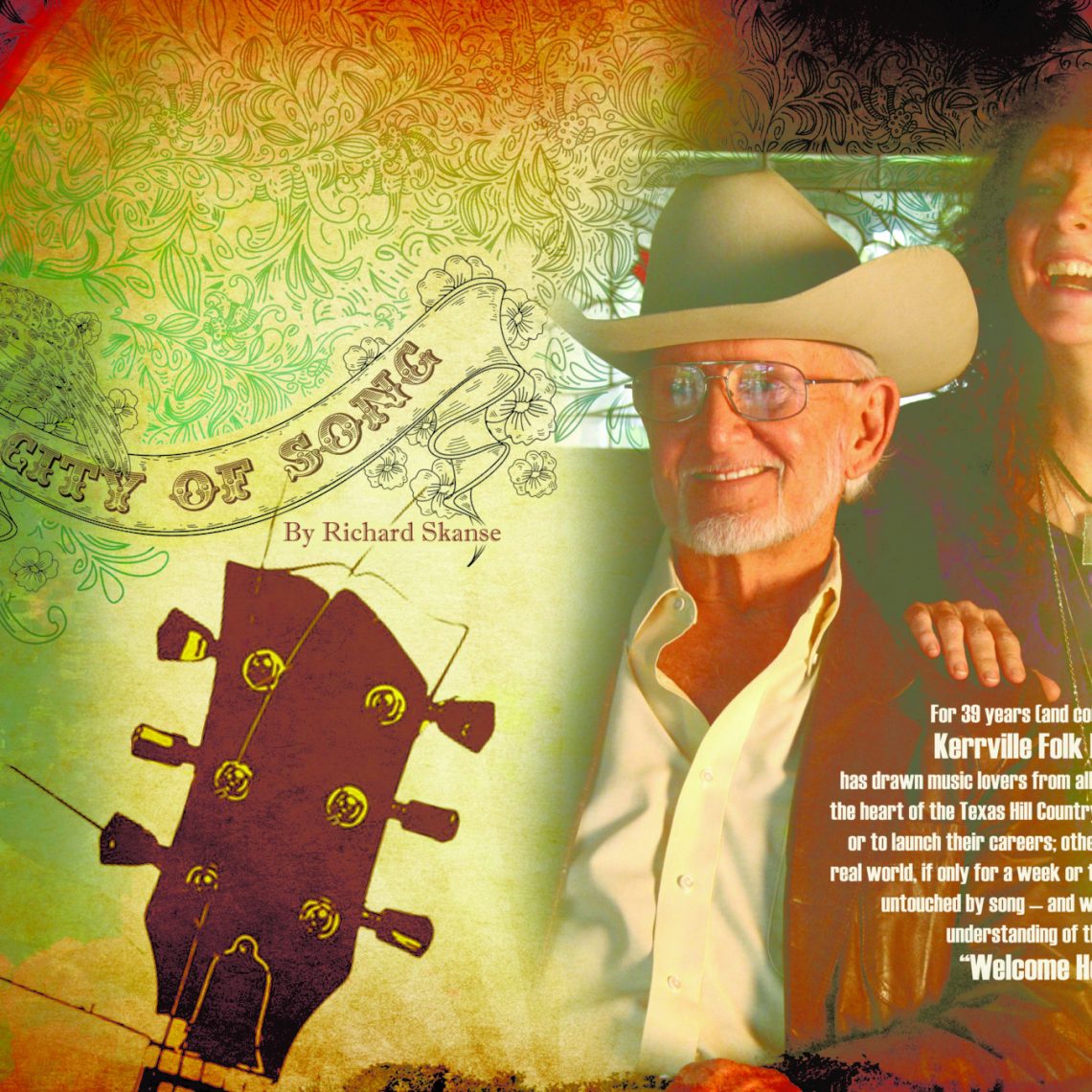

In the before and after, Quiet Valley Ranch can be a little too quiet. Come late morning or mid afternoon or early evening or whatever time of day it is on Monday, June 14, when the very last campsite is struck and the last of many, many hugs is finally exchanged, the 39th annual Kerrville Folk Festival will be over and the ranch will once again feel as empty and forlorn as it does on this rainy Wednesday afternoon in April. While waiting for a photographer to set up her equipment for a photo shoot, festival founder Rod Kennedy sits alone in the middle of the main stage and looks out over the empty outdoor theater that bears his name, his brow furrowed in fustration.

It has nothing to do with the coming deluge, though heaven knows Kennedy’s seen more than his fair share of those over the years. Nor does the ex-Marine, who turned 80 in January, seem all that bothered by any particular physical discomfort, even though it’s been only five weeks since he underwent knee-replacement surgery. He’s not out running sprints in the rain, but in 24 hours he’ll be hopping on a plane with his girlfriend, retired nurse Carolyn Pillow, for two weeks of vacation in Florida and the Cayman Islands, followed by another week of fun and sun in Maui in early May. (“I worked 16 hours a day, seven days a week, for about 30 years,” he explains with a shrug, “so …”) Kennedy doesn’t even seem to mind having to spend the day before his trip doing a photo shoot and conducting a lengthy interview; he’s patient and gracious, quick to flash a twinkling smile for the camera and a seasoned pro at recounting his eventful life story and the history of all things Kerrville in encyclopedic detail.

Oh, but that bank of lights laying haphazardly at the foot of the stage — left there, he guesses with a disapproving sigh, since last year? You can tell that’s driving Kennedy flat-out nuts. Ditto all the mounds of rolled up old carpet and other unsightly detritus onstage, not to mention that pile of tree limbs just laying out there in the field to the right of the theater benches, or the number of those benches that could use a fresh coat of Kerrville sea-foam-green paint, or the leak backstage, or this or that and 100 other things he probably can’t help but notice as part of the “what’s-wrong-with-this-picture” drill running through his brain. For more than half of his life, “Kennedy” was only his middle name — as in Rod Kennedy Presents — and eight years of retirement hasn’t entirely quelled his producer’s instincts. And so he frets and sighs and tsk-tsks over all that still has to be done before opening weekend in late May — even though he knows full well that his ultra-competent successor, Dalis Allen, and the rest of the festival staff and volunteers will have everything in order just in time to welcome the first wave of returning “Kerrverts” back “home.”

“We’re ready for you, Rod,” calls Allen, standing in the wings with Pillow next to Kennedy’s captain’s chair, from which he’s watched countless performances over the years. He stands and hobbles over to them with his cane, smiling for the camera as Allen plants a kiss on his cheek. “Somebody’s always kissing on you,” Pillow teases. “I don’t remember what event we were at the other day, but everybody was kissing him on the mouth. Where were we?” Kennedy, boyish grin brighter than the camera flash, answers back, “Who cares?”

Everyone laughs, and just like that — chaotic appearances aside — all is exactly as it should be on Quiet Valley Ranch. Because although the music and crowds and all-night campfire song circles are still a month and a half away, the first magic little moment of the 29th annual Kerrville Folk Festival is already in the books. And come 7 p.m. on May 27, when Allen takes this very same stage to greet the crowd and introduce the first act of the year (singer-songwriter Ana Egge), the City of Song will be in full bloom again.

***

FOR THE SAKE OF THE SONGS

Next year will mark the 40th anniversary of the Kerrville Folk Festival — a landmark that will most certainly (and deservedly) be recognized with much fanfare not only by artists, fans and staff at the festival itself, but by media outlets across Texas and probably far beyond. Although plenty of artists have enjoyed careers that long or longer, only a handful of other music festivals the world over have ever made it to or beyond the big 4-0. Sure, a little Google detective work will turn up things like the 62-year-old Ozark Folk Festival in Eureka Springs, Ark., not to mention the 53-year-old Monterrey Jazz Festival and maybe even the Library-of-Congress-certified “oldest music festival in the country,” the 152-year-old Worcester Music Festival in Massachusetts, though that last one is really more of a seasonal fine-arts series than a true festival. But when you narrow the search down to continuously running, multi-day music festivals dedicated to showcasing original music, Kerrville’s closest antecedent on U.S. soil is the Philadelphia Folk Festival, founded in 1962. (The famous Newport Folk Festival, which helped launch the careers of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, dates back to ’59, but was dormant from 1971-1985).

Granted, the big anniversary is still a year away. But given that Kennedy, without whom there wouldn’t even be a Kerrville Folk Festival, had a landmark birthday of his own earlier this year, we figured we’d split the difference and get an early jump on the celebration. Allen, who’s produced the festival since Kennedy’s retirement in 2002, can relate.

“I’m already scheduling people for 2011,” she says in early April, while still literally up to her ears in prep work for this year’s festival — which, frankly, might be hard to top. The first weekend alone features not only Kerrville mainstays like Jimmy LaFave, Terri Hendrix, Eric Taylor, Brave Combo and Sara Hickman, but major-label Texas country star Randy Rogers and 2010 festival brochure cover gals the Indigo Girls — arguably the festival’s biggest nationally known headliner in years.

All together, the three-week Kerrville Folk Festival and its weekend-long kid sister, the Kerrville Wine & Music Festival (held in the fall), constitute 21 days of programming — but putting all the pieces together is a full-time, year-round job. The evidence of this is literally all over Allen’s office. Her own little corner of the tiny festival office building on the ranch looks like the “before” picture in a before-and-after study on workspace makeovers, so stuffed with papers, folders, notebooks, posters and music that you suspect the adding of one more business card or CD to the pile would be hazardous to everyone in the immediate area. In addition to booking the festival, which among other myriad logistical details entails making travel and hotel arrangements for every songwriter and band and crew member, Allen is also in charge of managing all of the submissions for the Kerrville New Folk Competition for Emerging Songwriters.

“We had close to 700 entries this year — that’s 700 artists with two songs each,” she says. “I listen to all of them, and then we have an online system where 30 to 40 other people have about a month to listen to them. At the end of the deadline, I take all of their scores and my scores, and from there we end up with the final 32. I spent all day yesterday and all day Friday listening to submissions, and I still have a couple hundred to go.”

Songwriters who make it to the “final 32” will get a chance to perform at Kerrville’s famous New Folk Concerts, held the first weekend of the festival at Quiet Valley’s second stage, the Kenneth Threadgill Theater. After that, it will be up to this year’s judges, songwriters Susan Gibson, Tom Prasada-Rao and Ronny Cox, to select the “winners”: six new names to join the ranks of such past New Folk champions as Tom Russell, Vince Bell, Eric Taylor, Tish Hinojosa, Robert Earl Keen, James McMurtry, Slaid Cleaves, Ray Bonneville and BettySoo. Meanwhile, the remaining 26 contestants who “tie for second place” can forever commiserate with fellow New Folk finalists like Lucinda Williams, Steve Earle, Nanci Griffith, Lyle Lovett and Jimmy LaFave.

Add to that distinguished list of New Folk alumni even a smattering of the hundreds of other notables who’ve played the festival over the last four decades — including Mance Lipscomb, Willie Nelson, the Flatlanders, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Rodney Crowell, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Kevin Welch, Iris DeMent, Terry Allen, Janis Ian, Jimmy Driftwood, Eliza Gilkyson, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Jerry Jeff Walker, Steven Fromholz, Billy Joe Shaver and even Peter, Paul and Mary — and you’re still only scratching the surface of what the Kerrville Folk Festival is all about. Because no matter how famed and acclaimed many of the artists on the “main stage” lineup may be, people come to Kerrville year after year first and foremost to hear and share songs, not to see the biggest names in music (“folk” or otherwise). The only stargazing at Kerrville is done out on the sprawling campgrounds after dark, when anyone with a guitar can find themselves swapping songs with … well, it really doesn’t matter if its Butch Hancock, Gary P. Nunn or some dude who works for the phone company back in the “real world.” Because here in the Never Neverland of Quiet Valley Ranch, for three decidedly unquiet weeks every May and June, they’re all equals — if not practically family. Some may be better pickers, singers and far better writers than others, but anyone with an original song to share and a modicum of patience will get their turn and an attentive audience.

And there’s even more opportunities come daylight. Although the main stage performances don’t begin until early sundown, throughout all 18 days of the festival, songwriters by trade and hobby alike gather around the “Ballad Tree” and at Steve Gillette’s (of “Darcy Farrow” fame) “Texas & Tennessee” daily song circle/critique sessions. There are also staff concerts, children’s concerts, and even various music seminars, workshops, and a three-day, registration-required Songwriters School.

“I think from the beginning, Rod wanted to create an atmosphere where people could exchange ideas and work on the quality of their songwriting,” says Gillette. “And that’s what makes the festival so attractive to me. Because every year until I’m 90 years old, I can still live and grow as a writer, and going to Kerrville is like going to the well.”

Guy Forsyth, one of the many performers on this year’s lineup who will almost certainly find his way out to the campgrounds at least once during the festival, concurs. “There is nowhere I imagine you could go that has more songwriters per capita, per square mile, in the whole world than the Kerrville Folk Festival,” he marvels. “If you’re interested in learning how to be a songwriter, you could go and camp at Kerrville for two weeks, and even if you never saw a single show on the main stage, but just wandered around from campsite to campsite with your ears and a guitar, you would probably learn more about songwriting than you would by getting a college degree in it.”

But even though Quiet Valley Ranch may be as overrun with songwriters (professional or otherwise) during the festival as the Hill Country roads are with deer after dark, there’s no entrance exam or audition to get in. Because along with drums and stereos in the campground, exclusion and elitism are strictly frowned upon here, which means that that “Welcome Home” sign at the front entrance applies to seasoned Kerrverts and first-time “Kerrvirgins” alike, and you certainly don’t have to be a songwriter to feel welcome here and enjoy the festival to its fullest. And whatever stereotype-based misconceptions you might harbor about folk festivals and folk music and the folks that make and/or love it, you don’t have to be a Birkenstocks-wearing, tie-dye-sporting, hybrid-driving, protest-marching, hippie-dippy left-wing vegetarian tree-hugger, either. Heck, so long as you come with music in your heart, you can even be Republican.

Just ask the guy who started it all.

***

SIMPER FIDELIS

As legacies go, one could do a lot worse than “only” leaving behind an institution that’s meant so much to so many people as the Kerrville Folk Festival. And though he shows no signs of being in any hurry to leave just yet, when it comes time for Rod Kennedy to move on up to that big campfire song circle in the sky, his name will forever be associated, first and foremost, with what is unquestionably his greatest production. But the Kennedy that organized the very first Kerrville Folk Festival back in 1972 was no whippersnapper wunderkind fresh out of college. He was 41 years old, and you could easily fill a book just by chronicling the very eventful first four decades of his life … or at least the first seven chapters of his 379-page memoir, Music From the Heart, published in 1998.

“You can skip all of this stuff,” Kennedy offers as he flips through the tome at the dining room table in the house he shares with Pillow in a Kerrville subdivision. “You oughta start with the Chequered Flag, which is what led to me doing festivals.”

But no, it turns out that Kennedy had already produced a successful festival or two even before he opened Austin’s first (and last) racecar-themed folk music club (“Folk songs and fast cars!” was the slogan) in 1965. In 1964, he debuted his KHFI-FM Summer Music Festival, featuring six nights of free concerts at Austin’s Zilker Hillside Theater. It may have been tiny compared to today’s massive Austin City Limits Music Festival, held in the same park, but 15,518 fans, glowing reviews and an eclectic lineup including everything from Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins to Chuck Reiley’s Alamo City Jazz Band to classical music (string quartet and full orchestra) was nothing to slouch at. Clearly, Kennedy was a natural when it came to organizing and staging music events on a large scale. He also knew a thing or two about owning and operating radio and TV stations, racing (and collecting) “midget” Italian race cars and even carrying a tune; as a teenager in the ’40s in his native Buffalo, he played the cotillion and private party circuit as the “boy singer” for the Bill Creighton Orchestra.

Kennedy would later draw on all of those experiences (save, perhaps, for the racing stuff) during his Kerrville era. But more than any other chapter from the first half of his life, it was his three years of combat duty as a Marine during the Korean War that had the most profound and life-changing impact on him. “War was the loudest, most disorienting experience I’ve ever known,” he wrote in his book. “The noise, death and destruction, pain and tragedy were close to unbelievable. And, when it was all over, no ground had been taken or given. … We heard on our way home, after a year had passed, that out of an original battalion of 1,050, only 200 came home …”

“I didn’t know why I didn’t get killed along with over half of my battalion,” he says today. “But I knew I was going to have to pay back, somehow.”

Under the banner “Rod Kennedy Presents,” he began producing all manner of theater shows, concerts and outdoor festivals in and around the Austin area. Classical, big band and jazz music were his first loves, but he also developed a strong affinity for blues, bluegrass and traditional and contemporary folk music. Somewhere along the line, he became friends with Texas folk singers Carolyn Hester and Allen Damron (who was also one of his business partners in the Chequered Flag), and with Geroge Wein, founder of the Newport Folk Festival. It was Wein who first connected Kennedy with Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul and Mary, when the folk icon needed a road manager for a few Texas dates on his first solo tour. They bonded straight away over their shared love of music and songwriters, even though, politically, they made for as odd a couple as Mary Matalin and James Carville.

“I thought he was a left-wing bomb thrower at the time that he was doing all the stuff that Peter Paul and Mary did,” Kennedy admits. And though it may have been one of his other folk singer friends, Tom Paxton, who called Kennedy “a God-damned Republican,” the thought probably crossed Yarrow’s mind a time or two, too.

“I found him to be personally very self-contradictory,” Yarrow says of his initial take on Kennedy. “He was, on one hand, very open and warm and authentic. And then he would lapse into his post-Marine perspective, and be a really blotto, biased kind of guy who was very rigid about his evaluation of certain things. He was fiercely judgmental in the military way he viewed behaviors or activities that he considered to be ‘un-American.’ But that was overwritten by his decency as a human being, because his heart and his humanity was always very much there and very special, and his respect for musicians was phenomenal.”

Kennedy had recently been asked by the Texas Commission on the Arts and Humanities to put together “some kind of Texas music” event to unofficially coincide with the new Texas State Arts and Crafts Fair to be held in Kerrville. The concert had to be produced by the private sector so as not to conflict with the state-funded Texas Folklife Festival in San Antonio. Kennedy was game, and the first Kerrville Folk Festival was set for June 1-3, 1972, at the Kerrville Municipal Auditorium. Performers would include Damron, Hester, Lipscomb, Steve Fromholz, Michael (Martin) Murphey, Kenneth Threadgill and a band called Texas Fever featuring one Ray Wylie Hubbard.

Yarrow wanted in on the fun from the start. In addition to offering to play the festival himself, he also sold Kennedy on the idea of adding a showcase for new songwriters modeled after the New Folks Concerts he’d been in charge of at the Newport Folk Festival during the ’60s. The “s” was dropped and New Folk was born. Although no winners were officially announced at that first year’s “competition,” which unlike the rest of the festival was held outdoors during the day, Yarrow and Kennedy did hand-pick one act to come inside for a main stage showcase: a scruffy band of Lubbock guys (Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Butch Hancock and Joe Ely) who called themselves the Flatlanders.

“It was all kind of mind boggling,” recalls Gilmore. “I remember this entourage of Secret Service guys came by, and it turned out Lyndon Johnson was there.”

“I remember looking down on him in the front row, and he had shoulder-length hair,” adds Ely. “He looked like an old hippie. I kept thinking it was my old uncle J.B. from Petersburg.”

The festival’s maiden voyage was deemed successful enough to warrant a sequel, so Kennedy booked the auditorium again for the following May. Damron, Hester, Yarrow, Fromholz, Murphey and Threadgill were all back for encore performances, along with B.W. Stevenson, Townes Van Zandt, Jerry Jeff Walker and Willie Nelson. Even with the music now spread out over five days, it was clear the festival would need to find a bigger home if it was to continue. By year’s end, Kennedy and his wife, Nancylee, had sold their house in Austin and moved onto their newly purchased, 63-acre spread nine miles south of town. They had to work around the clock for months to get Quiet Valley Ranch ready in time for the third annual Kerrville Folk Festival (May 23-27, 1974). They pulled it off, though the campgrounds weren’t opened to the public until Kennedy’s next major production, that fall’s Kerrville Bluegrass and Country Music Festival (a Labor Day weekend tradition for 19 years before Kennedy became a wine connoisseur and it evolved into the Wine & Music Festival, aka “Little Folk”).

Although it would be several years before it grew into a three-weekend affair, the spirit of the Kerrville Folk Festival as it is known and loved today was already very much in place by the mid-70s. The campfire culture was in full swing, the main stage lineups were consistently solid and the New Folk competition was fast becoming a benchmark for success in a field of music in which earning the respect of discerning fans and one’s peers was deemed more important than mainstream airplay or record sales. Behind the scenes, though, Kennedy often found himself hanging on by the skin of his teeth, as year after year of pounding rains kept the festival in the red. As he put it bluntly in his book, “We were actually flying on unfunded optimism.”

The Kerrville Folk Festival is now run under the umbrella of the Texas Folk Music Foundation, a non-profit 501c. Yarrow frankly opines that the festival should have been a 501c years ago, but Kennedy was determined to keep the whole thing privately run. By the end of the ’70s, though, he did begin selling stock and loan packages to help with cash flow. The ’80s were just as touch and go; in 1987, the first year that the festival was stretched to three weekends, it rained 14 out of the 18 days. But like the hero in an old Saturday matinee serial, Kennedy always managed to bounce back for another thrill ride the following year. Granted, he didn’t do it alone: the numerous “Folk Aid” benefit concerts by Yarrow and other friends of Kerrville certainly helped bail the festival out of a tight spot or two, as did the introduction in the mid-80s of a few key corporate sponsorships (including Texas Monthly and Southwest Airlines). But at the end of the day, it was Kennedy’s unflappable commitment — Semper Fi! — to the music that kept him going.

“I’ve seen him in desperate states, but I never felt that he was going to throw in the towel,” Yarrow says. “It just wasn’t in him to do that. Maybe that was the discipline of his training in the military — he was hyper-dedicated and had extraordinary determination. But mostly, the fact is, he was in love with this.”

It wasn’t just his love of the festival, though. It was his genuine belief in the importance of the songs and their need to be heard. Kennedy may claim to have been a proud Republican all his life until two years ago, “when Obama appeared on the scene,” but he was always tuned in to the decidedly hippie ideal of music as a viable agent for change for a better society.

“I never booked an artist because they were popular,” Kennedy insists. “I booked them because I thought what they were doing met my standard of excellence: It was music from the heart, that spoke to people, made people realize that they weren’t the only ones suffering under a certain problem — it could be loneliness, it could be lack of self-confidence, it could be poorness or it could be the way other people treated them for being fat or short or whatever else. And I felt that our music could bring an end to that kind of treatment of people. I was adamant about it. And I am to this day.”

***

ALL IN THE FAMILY

True to the spirit of the festival, committed Kerrverts are, as a general rule, an open, sharing lot. Getting them to talk at length about the festival is disarmingly — and sometimes alarmingly — easy. What’s surprisingly hard, though, is getting them to pick a single favorite memory — that one perfect Kerrville Folk Festival moment that stands out from the crowd of thousands. What you usually get is an answer along the lines of, “Wow … gosh … I guess that’d be … well, honestly? There’s just too many … I wouldn’t know where to begin …” Now and then they might finally light upon a particularly magic song they heard around a campfire at 3 a.m., but more often than not, they’ll just launch into a sincere rhapsody about the “vibe” or the “people.”

Sometimes, though, you do get lucky. Like when you find one of those most fortunate of all Kerrverts who was there on the night of May 25, 1980, when the Joe Ely Band played chicken with arguably the meanest thunderstorm to ever beat down on Quiet Valley Ranch. It was a classic unstoppable force vs. immovable object showdown, played to a technical draw but with the band’s tenacious performance forever cemented in festival legend.

Lyle Lovett was in the crowd that night 30 years ago, and he remembers it as though it was yesterday. “It was packed that night,” Lovett says. “Joe Ely and his great band — you know, that great band that played on his early records, like Honky Tonk Masquerade — had come in from somewhere on the road and they had just made it in time to take the stage. And right as Joe stepped up to the microphone, there was a bolt of lightning and this big storm just seemed to suddenly come up — and they just kept playing. I’ll never forget the way Joe just stood there at the mic … it was really a powerful thing to see.”

Even Lloyd Maines, whose runaway-train pedal steel playing was as lethal a weapon in that band’s arsenal as Jesse “Guitar” Taylor’s dynamic blues licks and Ely’s Clash-approved rock ’n’ roll swagger, recalls the whole scene with awe, as though he were a mere witness rather than an active participant. “That was epic,” he enthuses. “I think we’d actually played maybe two songs, and then the storm started coming in like crazy. I mean, the wind was just blowing like hell.”

Kennedy came onstage to apologize about having to shut the show down. Apart from the danger to the crowd and band posed by lightning, there was the matter of the wind rocking the speakers so bad that they had to be taken down. “But we still had power,” Maines says. “And Joe had this Fender Super Reverb amp, and he just happened to have a high-impedance mic in the back of it with a plug that he could plug straight into the amp, so we finished out the show with Joe just singing through that amp. There was a huge crowd there, and about half of them stayed and just packed up against the stage. The band was dry because the stage was covered, but the crowd just got soaking wet. But they hung the entire time. It was absolutely just a magical night — one of those high-energy, Mother Nature moments.”

Ely himself adds that Kennedy, undoubtedly fretting about any number of liability issues, was less than thrilled that the band refused to yield to the storm after he’d tried to stop the show. “But we had just driven non-stop 2,000 miles from Duluth, Minn., and we were not about to not play that gig after driving that far,” he says. “I was not invited back after that — but we went out in style!”

Ely wasn’t the only Kerrville performer — or Flatlander, for that matter — who one way or another got sideways with Kennedy during the first 30 years of the festival. “Rod once banned me for life,” laughs Jimmie Dale Gilmore. “When I got a major-label record deal and started touring all the time, I got another gig that I just couldn’t turn down and had to cancel my Kerrville engagement. And I did it quite a bit ahead of time, but Rod didn’t like that at all. It was even in the Statesman the next day: ‘Gilmore banned for life from Kerrville.’ But then I came back the next year.”

Meanwhile, Butch Hancock still gets a kick out of telling the story about the time Kennedy sent him back out onstage for “one more song,” and he obliged with a 30-minute opus. “There’s something like 14 verses, and every verse is about as long as a normal song, so it just went on and on and on,” Hancock says. “I could see Rod out of the corner of my eye, trying to give me the cut-the-neck sign. And then at some point, he finally just left the whole campground I think. At least from what I heard. At any rate, for at least several years, he never asked me to do another encore.”

Even Eliza Gilkyson managed to get herself banned from the festival for several years. Kennedy, who prided himself on running a disciplined, family-friendly show, was not amused when she dropped the “f-word” onstage — an act Gilkyson concedes was “utterly inappropriate” on her part.

“I have some last thoughts on the time I did that, and concerning others who had their own sundry battles with Rod,” she commented via e-mail. “My conclusion, in retrospect, is that poor Rod was the unfortunate recipient of our last vestiges of parental acting out. Being as we had all at least by then left home, he became our surrogate father figure, and we all had to go up against his rules at one point or another just to butt our heads against something vaguely authoritarian! How’s that for a psych 101 analysis? Anyway, all is long forgiven, at least on my part.”

It’s clearly long forgiven on Kennedy’s end, too, as Gilkyson was invited to perform at his 80th birthday tribute this year at the Paramount Theater in Austin. So were all three Flatlanders, along with a veritable all-star list of other Kerrville favorites from the very beginning up to the present: Ray Benson, Marcia Ball, Robert Earl Keen, Jimmy LaFave, Terri Hendrix, Ruthie Foster and Randy Rogers. Naturally, there was a little good-natured roasting of the birthday boy on the stage that night, but just like the music, it was all delivered with genuine affection. Kennedy says he could see, hear and feel the love “coming over that stage like the Niagra Falls.”

It’s a memory that now probably ranks right up there at the top of Kennedy’s own favorite Kerrville moments. But it’s one he might not have lived to see had he not retired eight years ago. He managed to steer the ship through thick and thin (literally to the point of bankruptcy) for three long decades, but that last five years or so may well have been the roughest. His book follows the entire journey in painstakingly meticulous detail right up until the end of 1996, which he sums up as “Kerrville’s most exciting and successful year.” But instead of ending with “happily ever after,” the last six graphs read like he dashed them off right after the ship hit an iceberg. Three major corporate sponsors bailed all at once, his ex-wife (but still friend) had a serious car accident, and the pump to the ranch’s entire water system went kaput, all in a matter of weeks.

“I knew I should end my book here,” he finished his memoir with “uh, gotta go now” duress, “and maybe re-title it Hit or Myth, the story that begins with a whimper and ends with a bang!” A brief epilogue, tacked on right before the book went to press a year later, offers a little relief: the arrival of a new sponsor in Elixir Guitar Strings, an encouraging update on Nancylee’s recovery, and even a little joke about the epilogue actually being Chapter 12, because “we did not want to end this book with a Chapter 11.”

Better that, though, than the unwritten Chapter 13, which might have opened with Kennedy’s heart attack in 1998 and ended with him selling his majority stock in the festival to — long story put politely short — “a fellow with a lot of problems.”

“I just had to get out of there or I wasn’t going to make it,” he says today. “Too much stress.” So much stress, in fact, that Kennedy now says that for the first year or two after his retirement, “I never wanted to hear another folk singer or deal with another artist or manager or agent. I hated everything.

“I’ve never told anybody that, so don’t headline it,” he adds with a worried smile. “But anyway, after awhile, I began to get backstage again, and I’d see the people coming back every year, people that I had known for 34 years in this business. And hearing their songs again had the same effect on me that the original songs had, which was to open my heart and my mind and get me to back off a little bit. And now I miss it every day and every moment that I’m not there. Not so much doing the work, but really enjoying the music. And with the exception of last year, I’ve been there practically every night. And I’m going to be back there again this year.”

Then he looks over and smiles warmly at Allen. “Because it continues,” he says confidently, “with this one.”

When Allen stepped into her job as only the second producer in the Kerrville Folk Festival’s existence, she wasn’t exactly new to the gig. She ran her own booking agency for years in Houston, and, give or take a few festivals that she missed in the ’80s, she’s been part of the Kerrville family going all the way back to ’72. She was running a coffee house at the University of Houston back then, and was personally invited by Kennedy’s old Chequered Flag partner Damron to come check out “this thing happening in the Hill Country.” She worked as a volunteer at the festival for several years before finally taking a full-time job running the office. Her first production was 2002’s Wine & Music Festival.

Her job is, in different ways, both easier and more difficult than it was for her mentor. Whereas Kennedy ran the entire operation — from booking talent to ranch maintenance to fund-raising — like a “benevolent dictator,” Allen handles only the creative end (booking, scheduling, MC’ing) and some day-to-day business during the festival, and everything else is overseen by separate committees. The aforementioned fellow with problems was eventually pushed out of the picture by the stockholders on the Festival Board, which later became the Festival Operating Committee when the shareholders handed full ownership of the festival over to the non-profit Texas Folk Music Foundation. Quiet Valley Ranch, though, is still owned by the Ranch Board, which leases the property to the festival year round. Oh, and Who’s on first.

“It’s a bit complicated,” Allen admits with a laugh. “And I have to answer to all of them on some level. But as far as finding and booking the artists is concerned, I’m pretty much still autonomous on that part. Everybody figured out pretty quick that that’s exactly how it had to happen.”

Kennedy reaches across the table and squeezes her hand. “This is a business, but most people don’t know what this business is about,” he says. “The business is about people, and broken hearts and lonely hearts, and people who want to heal from what this festival has to offer. It’s not just a series of concerts. It’s a family whose roots are deeply embedded in each other’s well being. And I thank God this child has kept it going in the same way that I would.”

Indeed, the more things change, the more things stay the same. And Kerrverts wouldn’t have it any other way. Because for all that’s gone on behind the scenes, at the end of the day, all that matters is that the Kerrville Folk Festival continues to offer all of the things that have kept people coming back for (almost!) 40 years now. And between Allen’s Kennedy-instilled commitment to excellence and the Texas Folk Music Foundation’s protective stewardship, there will almost assuredly be a festival for those people to come back to for years and years to come.

“It’s an incredible thing to see when we have the early land rush for campground spots a week before the festival, and thousands of people come, every year,” Allen says. “The line on the highway is a mile and a half long,” Kennedy adds. “Everything from Cadillacs to cars that will hardly move, just bumper to bumper, with kids hanging off of them, waving their flags when they come by the office.”

Jimmy LaFave, a 1987 New Folk finalist, has been making the pilgrimage out to Quiet Valley Ranch now for 25 years. And he still gets a tingle every time. “When I pull up to Kerrville and walk through those gates, it’s like there’s a particular smell, you know? And I don’t mean the latrines! There’s just a certain feel, like the way the dust gets on your shoes, and when you first see that little ‘Welcome Home’ sign … it’s just an amazing vibe. And even though it’s changed a lot, that vibe is still there.”

Ruthie Foster has only been coming to Kerrville for the last decade or so, but it’s telling that she describes the thrill of turning off Highway 16 and into the festival driveway almost exactly the same. Like they’re singing the same song. There’s no place like Kerrville, there’s no place like home.

They come from all across Texas, North America and maybe even the globe, not just to hear and play music, but to reconnect with folks they may see only once a year but who they embrace at first sight like immediate family. Many reconnect, too, with their “other,” truer selves, happily exchanging their ties, button-downs and Florsheims for tie-dyes and Birkenstocks, and all the worries of their “regular” lives for a long but somehow never quite long enough vacation in an all together better and more spiritually invigorating world. One where it sometimes rains like a bastard and things may not always go exactly according to plan, except, of course, for the three assurances that count the most: songs will be shared, lifelong memories will be made and, before it’s all over, every Kerrvert left standing after 18 days and nights of nonstop music will come together to sing Bobby Bridger’s official Kerrville Folk Festival anthem, “Heal in the Wisdom.”

“It’s an amazing thing,” Hancock says. “I think with all these years of Kerrville, somewhere back in there, I began to see it as a little small city … Do you remember Brigadoon?”

He’s referring to the fictional Scottish town featured in the 1940s Broadway musical Brigadoon, which was later adapted for a 1954 Gene Kelly movie and, a decade later, a TV movie with Robert Goulet and a pre-Columbo Peter Falk. In the story, Brigadoon — along with all of its inhabitants — appears for one day once every 100 years, then mysteriously disappears back into the Highland mist.

“It’s sort of like that, except this one appears every year,” Hancock says. “It really is a great study of a city suddenly appearing out in the middle of a field, and then disappearing after, in this case, three weeks. And it’s wonderful that it comes out with the theme of music. Everybody that goes there, it seems they come away going, ‘Wow! I wish it could be this way the whole year round.’

“What a beautiful wish,” he continues. “People getting along with each other, singing songs and living together. It’s such a positive energy that just makes the whole thing something worth keeping — and worth being a part of.”

Thanks to Clair Devers for her help in interviewing Guy Forsyth, Walt Wilkins and Randy Rogers for this story.

RELATED

Camping Kerrville: After the main stage goes dark, the party’s just getting started

“Going Home”: Essay by 2008 Kerrville New Folk winner BettySoo

Campfire Girl: The story of Michelle Shocked’s Texas Campfire Takes

Go Fish: It just wouldn’t be a Kerrville Folk Festival without Trout Fishing in America

[…] LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, June […]