By Tom Buckley

(LSM June/July 2010/vol. 3 – issue 4)

Michelle Shocked could write a song about the origins of her musical career, and few would treat it as anything but imaginative fiction. Even before she’d arrived at Kerrville in 1986 — as a fan, not a performer — Shocked had experienced the sort of life inventive writers can only conjure.

She was raised a Mormon in Gilmer, Texas; ran away at 16; was twice institutionalized in a mental hospital — the second time on the insistence of her fundamentalist mother; put herself through the University of Texas, earning a degree in speech communications; was arrested for protesting at both the Republican and Democratic conventions in 1984, giving police the fake name “Michelle Shocked” — instead of Karen Michelle Johnston — at the latter; lived as a vagabond, roaming the country then hitchhiking through Europe; was raped by a fellow peace activist while in Italy; returned to Texas, where she was homeless while volunteering in the Austin music scene.

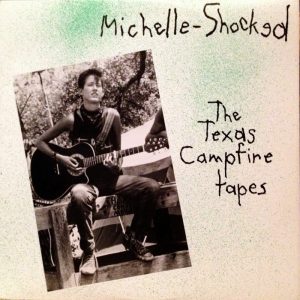

So maybe the next strange turn in her bio shouldn’t have been so unexpected. Swapping tunes around a Kerrville late-night campfire, Shocked caught the ear of British producer Pete Lawrence, who asked if he could record her on his Sony Walkman. The result was a muddy-sounding but charming set, with crickets chirping throughout and truck engines revving in the distance, that captured Shocked’s remarkable and raw talent. Little did Shocked know that her impromptu fireside session would be the vehicle for introducing her spirited voice and pithy songwriting to an international audience.

In fact, unbeknownst to Shocked, Lawrence returned to England and released the primitive-sounding performance as the Texas Campfire Tapes on his Cooking Vinyl label. The bootleg recording became a massive folkie hit, garnering critical acclaim and commercial success, and topping the British independent album chart.

In fact, unbeknownst to Shocked, Lawrence returned to England and released the primitive-sounding performance as the Texas Campfire Tapes on his Cooking Vinyl label. The bootleg recording became a massive folkie hit, garnering critical acclaim and commercial success, and topping the British independent album chart.

By this point, Shocked was living on the verge of homelessness in New York City, where she was working as a squatters’ activist, when a friend returned from Amsterdam with a magazine that included a flexi-disc of a song by one Michelle Shocked titled “Who Cares?” Baffled, Shocked soon discovered that the song was indeed hers, though mistakenly titled; she’d called it “Ghost Town,” and “Who Cares?” was just taken from a flippant introduction she’d given to the song at Kerrville.

She also learned that the album was being presented as a field recording of a new talent, stumbled upon by Lawrence in the manner of the Lomaxes (John, John Jr. and Alan) discovering folk and blues figures several generations earlier. But the album contained only about half the songs she’d sung, presented out of sequence and with most of her introductions and comments removed. And if that wasn’t enough, the low batteries in the Walkman meant the release was at the wrong speed, making Shocked’s voice sound higher than it really was.

So displeased with the results was Shocked that she couldn’t even bring herself to listen to the recording more than a time or two, ultimately dubbing the project the “Texas Campfire Thefts”. Nevertheless, once word of the album’s existence — and success — reached the ears of executives as Mercury Records, Shocked was offered an advance of $130,000 for her “follow-up” album (her breakthrough release, Short Sharp Shocked). To her credit, and remaining true to her political beliefs, Shocked accepted only $50,000, insisting that Mercury could use that extra money to finance other struggling alternative musicians.

In retrospect, and despite its production shortcomings, the Texas Campfire Tapes is a triumph of talent over technology. The collection of songs — imaginative, starkly honest, and sung in a way that blurs the edges between folk, country, blues and Texas swing — is a tour de force in which a fresh naivety mixes with a fine sense of vocal phrasing and subtle guitar picking. Shocked sounds so innocent — and so liberated. Songs like “The Ballad of Patch Eye and Meg” and the album’s closer, “The Secret to a Long Life (Is Knowing When It’s Time To Go),” clearly herald the arrival of a major talent.

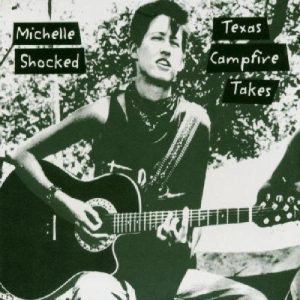

The story has resolution. In 2002, Shocked was given a copy of the original tape, unedited and in sequence, and went into the studio with producer Cheryl Pawelski, who brought the recording as close to the original speed as possible, while making the sound remarkably clearer. “I was playing a set list of what I was,” Shocked said then, “a blues-woman, a singer partial to swing and a Texas songwriter. But it was filtered through someone else’s perception lens.”

The story has resolution. In 2002, Shocked was given a copy of the original tape, unedited and in sequence, and went into the studio with producer Cheryl Pawelski, who brought the recording as close to the original speed as possible, while making the sound remarkably clearer. “I was playing a set list of what I was,” Shocked said then, “a blues-woman, a singer partial to swing and a Texas songwriter. But it was filtered through someone else’s perception lens.”

In 2003, the Texas Campfire Takes was released, the integrity of the original performance restored. The updated CD includes all 21 songs Shocked sang at Kerrville that night, a set that forecasted what was to come for the Texas singer-songwriter, who’d establish herself as an artist of depth and imagination, and one with a wide musical embrace.

RELATED

LSM Cover Story: Kerrville Folk Festival

Camping Kerrville: After the main stage goes dark, the party’s just getting started

“Going Home”: Essay by 2008 Kerrville New Folk winner BettySoo

Go Fish: It just wouldn’t be a Kerrville Folk Festival without Trout Fishing in America

This interpretation of what really happened around the Texas Campfire Tapes as told here is complete nonsense. Shocked was asked permission when it was suggested the album be released and indeed, I tracked her down to a squat in New York to discuss it all with her. In January 1987, she came over to the UK to promote the album and ended up not leaving for two years. She even slept in the office of Cooking Vinyl at my business partner’s flat at the beginning so knew exactly what was going on. We worked together to promote the album, get it licensed all over Europe and talk to major labels which resulted in her Polygram deal. Her attempts to re-write history are spurious at best. It’s shame she feels compelled to do this as the whole thing quite a fairy story and people are still loving that album now and its spirit. I would be happy to give an interview to provide some balance.

To ‘Pete Lawrence’ above. Do you have a photo or anything that would back your contention? Usually when artists go to record companies, cameras would pop out for photos. Anything in writing? If there was going to be a release you put nothing in writing? You went all the wat to New York yet you offered to put nothing in writing? Did you not have a pen? Maybe all the stores in NYC ran out of pens and paper that day, I’m sure. I’m just saying because I suspect you’re full of crap. All record producers are totally 100% honest though right?