By Richard Skanse

Talk about jumping right into the deep end …

When Hector Saldana left his longtime gig at the San Antonio Express-News to start his new job at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos last October, his very first project as the gallery’s Texas Music Curator could not have been more daunting — or, for that matter, fun. Earlier in 2017, a few months before Saldana’s hiring, the Wittliff had acquired the extensive archives of Texas (and American folk) music legend Jerry Jeff Walker: a veritable mountain of file boxes packed-full of everything from master tapes and unpublished songs to personal coorespondance, photos, posters, psychedelic gypsy songman road journals and all manner of colorful Lost Gonzo ephemera from the wild and wooly heyday of the 1970s’ progressive country explosion. Saldana’s job? Roll up his sleeves, dig in, and find just the right pieces to assemble an exhibit worthy of one of the most fascinating larger-than-life characters to ever hit the Lone Star State this side of Davy Crockett.

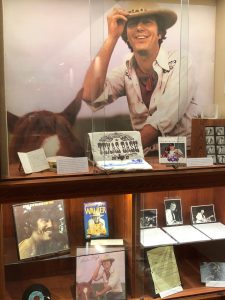

That’s right, he’s not from Texas … but Jerry Jeff Walker has been loved by Texas music fans as one of the state’s biggest icons ever since the ’70s. (Photo by Richard Skanse)

The result, aptly titled ¡Viva Jerry Jeff! The Origins and Wild Times of a Texas Icon, opened to the public on Feb. 5 and will be on display through July 8 at the Wittliff Collections gallery, located on the seventh floor of Texas State’s Albert B. Alkek Library. Although there was no formal grand opening, Saldana says that an invite-only reception party for “select fans” — organized by Walker’s wife and manager, Susan Walker — is on the books for March 25, in between Jerry Jeff’s two big annual birthday bashes at Austin’s Paramount Theatre and Gruene Hall. A second event, which Saldana describes as a “more of a panel on the exhibit, with Jerry Jeff’s participation” (and possibly even a performance) is still in the planning stages for sometime in early June.

In the meantime, Walker fans both “tried and true” (to borrow the name of his own record label, launched back in the mid-80s long before the DIY route became a paved and heavily trafficed highway to regional and even national success in American music) and those who might only know him as the writer of “Mr. Bojangles” or for his seminal 1973 album ¡Viva Terlingua! are invited to visit the Wittliff and peruse the exhibit at their own leisure. Just come prepared to stay awhile, and try not to get dizzy — because the sprawling career of Jerry Jeff Walker, even when carefully currated and handily timelined across four walls of a single gallery room, can be a lot to take in all at once. Hell, it’s taken Walker (who turns 76 on March 18) the better part of six decades to cover it all himself, seemingly reinventing himself completely multiple times along the way, from Woody Guthrie inspired gypsy songman to psychedelic folk-rocker to hard-partying Texas country rocker to master storyteller and elder statesman of American song. And he’s still not finished.

Jerry Jeff Walker during his “Gidget” years … before he actually became Jerry Jeff Walker. (Photo by Richard Skanse)

“To me, Jerry Jeff Walker is a chameleon — and he’s always been a chameleon,” observes Saldana during a Friday afternoon guided walk-through, pointing to high school picture of Walker from back when he was still just Ronald Clyde Crosby of Oneonta, New York. “Because this guy right here in the yearbook doesn’t really even look like that guy there on the beach, playing ukulele like Gidget — and that’s not even very far removed yet; that’s 1960, and that’s 1962, and it already looks like a totally different guy. But he was only doing Mills Brothers stuff or Kingston Trio songs then, in a lot of ways still just a normal kid singing popular songs from that first folk music boom.”

That “normal” kid (also a high school basketball star) would not be long for that world, though, let alone for the days of going by Ron Crosby. After skipping out of a very short-lived stint in the National Guard, he adopted the name “Jerry Ferris” (off of another man’s draft card that he’d used as a fake ID in his teens), discovered Jack Kerouac and Woody Guthrie and hit the road with no particular place to go but anywhere his whim blowed. Which is how he came to land in New Orleans sometime in 1963, at which point he elevated his game from street-singing hobo to couch-hopping coffeehouse folk troubadour, traded his uke in for an acoustic guitar, and dumped “Jerry Ferris” for “Jerry Jeff Walker” (Jeff just because, Walker after the blues piano player Kirby Walker). New Orleans was also where he recorded his earliest demos. And yes, those very tapes tapes are now part of the Wittliff’s Walker collection, too — though they didn’t come with the rest of the haul from Jerry Jeff’s own archives. Saldana actually hunted those down himself, along with the 35-mm negatives from Walker’s first attempt at a photo shoot.

The machine Jerry Jeff Walker’s New Orleans friend Jay Edwards used to make his first-ever recordings back in 1964 and 1965. (Photo by Richard Skanse)

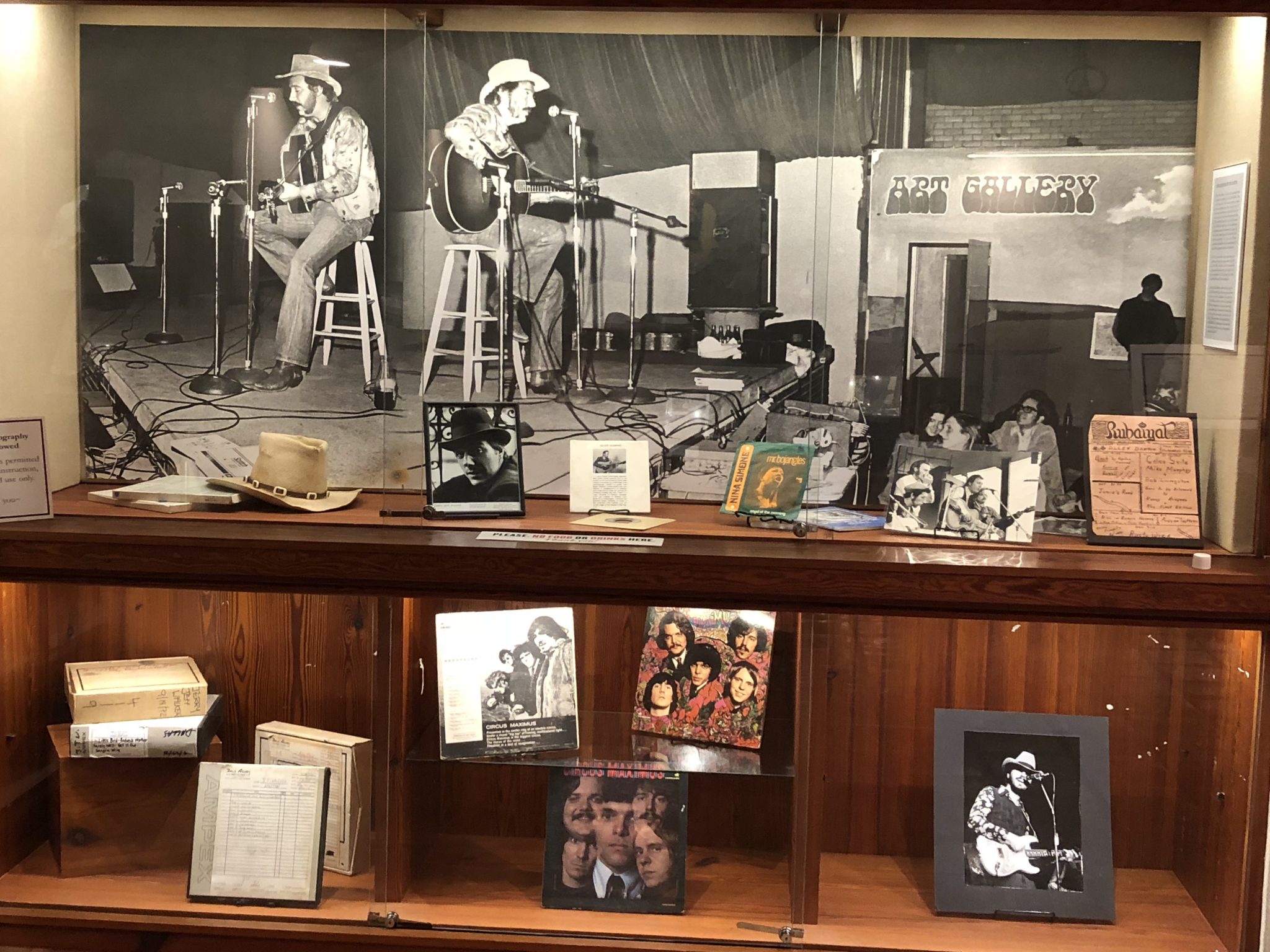

“To me, this is the part that I’m most excited about,” Saldana says proudly, standing before a display dominated by an accordion-sized portable tape machine and five shots of a 23-year-old Walker posing — like legions of earnest folk troubadours and rock bands to come later — in the middle of a railroad track. “That’s Jerry Jeff Walker in 1965, right around the time that he was inspired to write ‘Mr. Bojangles.’ And the new recordings that we recently acquired, some of them were actually recorded on that machine. I tracked all of that stuff down from this couple, Jay and Anne Edwards, who befriended Jerry Jeff in 1963 when he first started drifting in and out of the French Quarter. They ended up working on a songbook for him, which is why they made those recordings, and then it was Anne took the photos of him.”

While one of Anne Edward’s photos did end up being published, none of the music on those old tapes — about three-hours’ worth of material captured in 1964 and 1965, including both live coffeehouse performances and home-recorded demos — had ever been shared publically before. But Saldana had the tapes “baked” at a studio in San Antonio for restoration and transferred to digial files, which visitors to the Wittliff can now hear via the Jerry Jeff exhibit’s custom playlist. Down the line, after the exhibit closes, researchers will still be able to listen to the recordings by appointment, and some of the material might even find its way to official release, should the Walkers themselves so desire.

“I gave Susan digital versions of the 1964 and ’65 tapes acquired by the Witliff, and she is planning to use at least one song as a bonus track on his next album,” explains Saldana, who had the opportunity to show Jerry Jeff and Susan Walker the exhibit for the first time when they came down from Austin last week. “It was an extensive first look with Jerry Jeff narrating as he took it all in. He and I even sang through one of the unpublished songs about civil rights, whose lyrics we have on display.”

Saldana, it’s worth noting, is a seasoned performer and songwriter in his own right, having co-founded the San Antonio Tex-Mex rock band the Krayolas with his brother David while both were still teenagers back in the mid-70s, around the same time that Walker was ridin’ at his highest and wildest with the Lost Gonzos. But it was ultimately his years of experience as a music journalist — and lots of diligent research — that served Saldana best during the months he spent putting the ¡Viva Jerry Jeff! exhibit together. Because Walker spent a good portion of the last year laying low while undergoing (and recovering from) successful treatment for throat cancer, Saldana says that apart from a few phone conversations, he didn’t actually have much contact with the artist himself prior to their visit last week.

Jerry Jeff Walker shares a laugh with curator Hector Saldana while tripping through his back pages. (Photo by Mark Willenborg, courtesy the Wittliff Collections)

“So in one sense, there were definitely times when I felt like I was kind of putting this together with one hand tied behind my back,” Saldana explains, nothing that he would have loved to have “spent more time with Walker, just going over each item.” After all, he wasn’t just sorting through stacks of lyrics, letters, clippings, photos and boxes of master recordings colorfully labled things like “Jerry Jeff bullshit”; the archives also contained such curious artifacts as a 1962 scrapbok of Walker doodles and ramblings mysteriously titled The Ragged Rubber Fantasies of a Soft Giraffe. “What that means, I have no idea,” Saldana admits with a laugh. “But it’s an amazing scrapbook, because for all the youthful kind of drawings and puns and jokes, there’s also stuff in there about about civil rights. You can tell he was very in tune to the struggle of black people.”

In other words, Walker may have still been “Jerry Ferris” at the time, but he was already “woke” and well along his way down the hardcore troubadour path — and just five short but immensely transformative years from recording his first album, titled after the most famous song ever inspired by a night in a New Orleans drunktank: “Mr. Bojangles.”

Just a handful of the many phases and stages of Jerry Jeff Walker. “To me, he’s a chameleon,” says Saldana. (Photo by Richard Skanse)

And to think that was only Jerry Jeff Walker, Version 1.0.

“As much as I would have liked to have talked to him more, in the end, an exhibit like this really isn’t about going down memory lane with the artist; part of it is a critical assessment of the guy,” says Saldana. “And I always respected the guy, but I really came away from this with a lot of newfound respect for him. Because Jerry Jeff I’ve come to learn represents adventure as much as anything. He was rebellious, and he was always searching, looking for answers. He’s always had that desire burning in him, deep — because you can’t go through all that he has and do all the things that he’s done without that.”

The Wittliff Collections exhibit, ¡Viva Jerry Jeff! The Origins and Wild Times of a Texas Icon, runs through July 8. Gallery hours are Monday through Friday 8:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m., Saturdays 11 a.m.-5 p.m., and Sundays noon-5 p.m. For directions and more information, visit www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu.

It seems really sad that Jerry Jeff Walker never bother to come back to his home town to preform. It’s really kind of insulting to the people that live the in the area and he grew up with and went to school with.

That comment about Jerry Jeff not returning to his hometown (Oneonta NY) to perform is totally wrong.

JJW performed a special concert at the re-opening of the Oneonta Theater in 2010. It was sold out, and was attended by many of his hometown friends and even some of his high school teachers, though they were in their 90’s. I was there.

Beyond that, it is Oneonta that never gave a damn for JJW. Did they or any venue in town ever try to book a concert by him? NO. JJW visited his parents there frequently and was always available.