By Richard Skanse

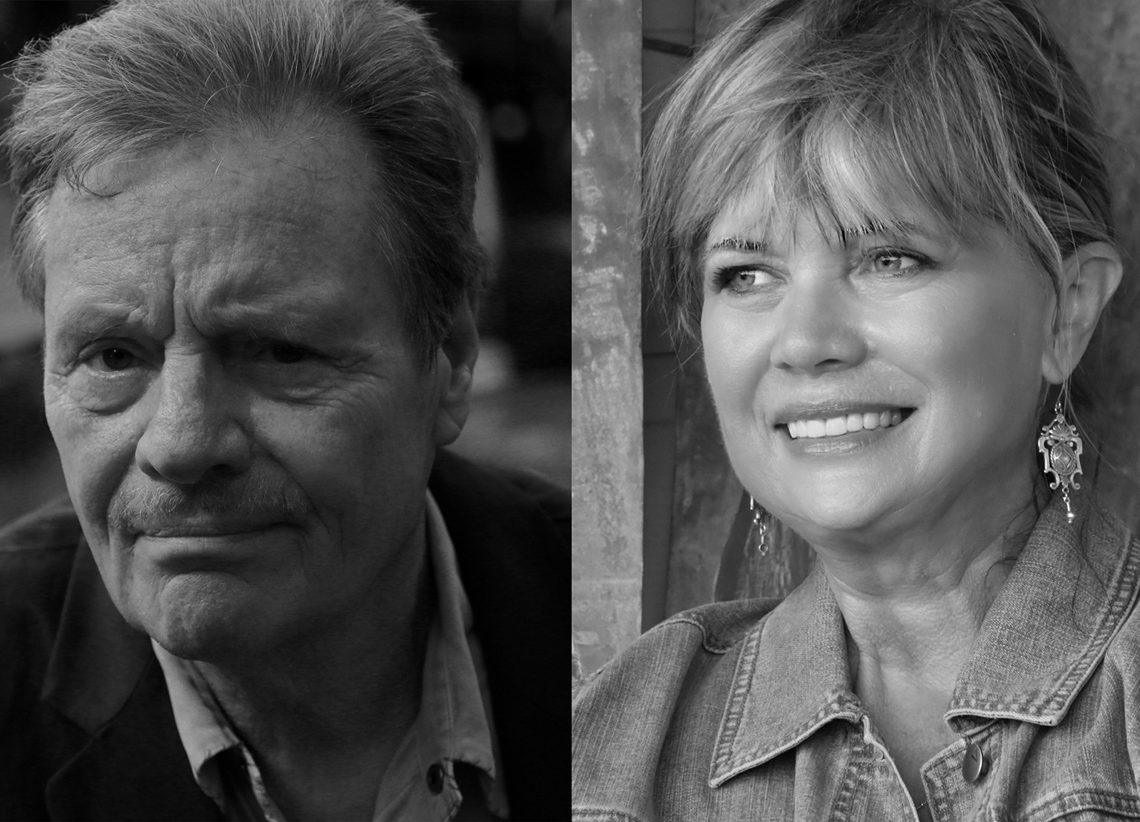

What a difference two years — and a helluva lotta dedicated hard work — can make. Back in January 2016, when Diana Finlay Hendricks embarked on her first Sandy Beaches Cruise, she was nominally a writer on assignment but still, for all intents and purposes, really just another lucky Delbert McClinton fan bound for a week of enjoying non-stop live music, adult libations and decadent buffet spreads in the Caribbean. But this weekend, when Hendricks sets sail for what will only be her second SBC voyage (and No. 24 in all for McClinton, who’s been throwing this all-star floating Americana, roots, and blues bash on the high seas every year since 1995), she’ll do so carrying the distinction of being not “just” any other Delbert fan, but the first to have literally written a book on the man himself. Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury may be the No. 1 bestseller in America at the moment, but for the next seven days, Hendricks’ just published (last month) Delbert McClinton: One of the Fortunate Few (The Texas A&M University Press) will undoubtedly be the most read book on board the Holland American luxury liner m.s. Nieuw Amsterdam all the way from Ft. Lauderdale to exotic port stops in Antigua and St. Kits and back again.

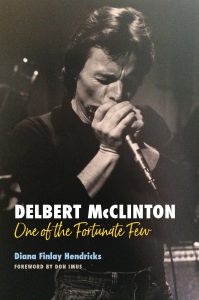

“Delbert McClinton: One of the Fortunate Few”

By Diana Finlay Hendricks (The Texas A&M University Press)

Although this is her first book, Hendricks’ credentials going into the project were rock solid. In addition to her decades of experience as a print journalist (including pieces for The Journal of Texas Music History and Lone Star Music Magazine) and her Master of Arts degree with an emphasis in Texas music and culture from Texas State University, she logged more than 20 years in the live music business trenches as the co-owner of Cheatham Street Warehouse in her native San Marcos, Texas. McClinton played that legendary tin joint by the railroad tracks a time or two himself back in the heyday of the ’70s progressive country boom, though by then he was already hundreds if not thousands of sweaty gigs into his genre-blurring performing career that last year hit its 60th anniversary. That epic run gave Hendricks a lot of ground to cover, but as she happily discovered early on in her research, McClinton has been a bit of a self-professed hoarder his entire life. His treasure trove of journals, travel logs, song notes, and all manner of other personal ephemera dating all the way back to his early childhood in Lubbock proved a biographer’s dream — as did Delbert’s own steel-trap of a memory and candid forthcomingness over the course of their many hours of interviews. Hendricks also interviewed dozens upon dozens of other sources, ranging from some of McClinton’s earliest bandmates and associates to such longtime friends and fellow artists as Bonnie Raitt, Marcia Ball, Terry Allen, Glen Clark (of Delbert and Glen fame), and of course Bruce Channel, whose smash hit “Hey Baby” showcased Delbert’s formidable harmonica chops and netted the Fort Worth pals a trip to England in the early ’60s and a date with an up-and-coming band of Buddy Holly worshiping lads from Liverpool.

Of course, every McClinton (or Texas music) fan no doubt already knows — or arguably should know — that little nugget of Delbert history. But there are countless others stories every bit as remarkable filling out the rest of One of the Fortunate Few, making it an essential read for any Delberthead or serious connoisseur of Texas and American roots music. To find out more about how author and subject collaborated to tell as many of those stories as they could, we caught up with both Hendricks and McClinton via a conference call the week before Christmas, right after they’d both returned home — San Marcos for her, Nashville for him — from a successful whirlwind book tour of New York City (complete with a visit with Don Imus, who penned the book’s forward.)

Good morning, everybody. Delbert, I think the last time I really interviewed you was way back on the 2003 Sandy Beaches Cruise. It’s been a long time!

McClinton: Well, everything’s been a long time for me. [Laughs]

Going even farther back than that, can either or both of you remember when you first crossed each other’s path? Delbert, did you ever play Cheatham Street back in the day?

McClinton: Oh yeah, sure …

Hendricks: But you know, we didn’t really connect for this project until (mutual friend and Austin music scene den mother) Nancy Coplin put us together through Wendy, Delbert’s wife. Wendy was looking for somebody to write a bio for his new record at the time, and Nancy told her to call me. And that’s kind of how it all started. I think it was actually about three years ago this month.

That’s really not that long ago. Y’all covered a lot of ground in that time!

Hendricks: Well, I have to say I started this as a career journalist going in to write an unauthorized biography that was blessed by Delbert and Wendy, and by the time the project was over, I just fell into feeling like family. Whether they wanted me to or not!

Delbert, had you ever been approached to do a book before?

McClinton: No. She was the first one that ever suggested that. I’d been writing some over the last several years, but you know, it was just bits and pieces of things; I hadn’t put anything together in a coherent sense as far as writing a book myself. But I’ve spent a lifetime saving stuff.

Hendricks: And that made my job really easy. He had notes and tickets and scratch paper that goes all the way back to his childhood. The first thing Delbert ever had published was a Christmas poem that he won a contest with in school. It was published in his high school newspaper, and he still had that newspaper.

It pays to be a hoarder!

McClinton: I’ve been a pack rat about stuff like that all my life. It always seemed to me like it was important. I mean, it’s not really important, it is what it is, but … all through the years, it was really important to me to save little bits and things. I’ve got trunks and boxes with notes in them. If nothing else, I did it for me, I guess. I hate to throw anything out.

Hendricks: And one of the really exciting things for me about working on this project was getting to look through all those notes. I mean, Delbert will tell you that he sat up on the side of the bed and wrote “Two More Bottles of Wine” in about 20 minutes, and he still has that original copy. And it just really flows — there’s a couple of things that he’d marked out and changed, but it was all pretty much the same as you still hear it today.

It’s pretty cool to see so many pictures all of that stuff in the book, too.

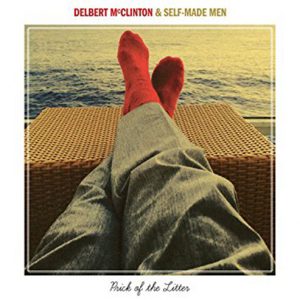

Hendricks: Absolutely! I’m glad that he shared all of that for his kids, but more than that, I’m glad that we get to share it with everybody else. Because Delbert’s story really is like a story of the American dream. And it tells the story of Americana music in its truest form. Going all the way back to his childhood in Lubbock, listening to Bob Wills and Hank Williams, to playing the roadhouses on the Jacksboro Highway in Forth Worth, to moving out to L.A. to make his first records at the start of the progressive country movement and then all through everything since then … He just went through so many musical scenes, and continues to go through different musical scenes. I mean the last album he did (Prick of the Litter, released early last year) is different from any other one he’s ever done, and he’s got a new album in the works right now that’s going to add a new dimension. It just keeps getting better.

Delbert, did you have any reservations about this project? Modesty aside, did you have any doubts about inviting somebody in to really go digging as deep as Diana did — not just all through your professional career, but your personal history as well?

McClinton: You know, I still don’t know what to think about it. I mean, a book written about me? How do you get your head around that? I don’t know. And the fact that she did it with such enthusiasm … I guess it confused me a little bit. Just because — I mean I don’t want to sound stupid saying this, but in a sense it almost just seemed like a bunch of hoopla to me!

Hendricks: Well, when you were right there on the front row, maybe it didn’t seem that special! But when you look at the big picture … There were a few things where Delbert was like, “I don’t know if anybody’s going to want to know this,” but I mean, through the ’70s, his band was traveling in a pick-up with a camper shell and a trailer, and in that camper shell they would literally sleep on the mattress that Delbert was born on. As the sleeping bunk. Somebody would drive, somebody would sleep, and they would just pile in and go. And sometimes they’d play for just enough money to buy gas to get to the next show. And at one point he told me, “Well I don’t know if we want to tell anybody that.” [Laughs] But that’s truly … I mean, what a great pioneer story.

Delbert, how well do you actually remember those times? Can you still vividly recall sleeping on that bed in the back of that truck, or did Diana have to help you sort of reconstruct those memories after going through your journals and talking to other people?

McClinton: Oh, that’s the kind of stuff you just don’t forget! The funny part is, before I put that mattress in there and got a camper for my pickup, we were renting station wagons. Five guys in a station wagon, and it was hell. So I put that mattress in there, put a camper top on it, and then two guys could ride up front and the other three could lay in the back and sleep.

The lap of luxury!

McClinton: Well, we felt it was an upgrade! Because any time you can stretch out, you’ve got a good spot.

Hendricks: Speaking of road trips, you might have read some of this in the book, but a lot of times when people like Jimmy Reed would play out on the Jacksboro Highway and Delbert’s band would back them up, they’d say, “Hey come back us up in Lawton, Oklahoma, too.” Delbert, tell him about some of those trips.

McClinton: Well, we worked with Jimmy Reed a lot back in the ’60s. Jimmy Reed and Howlin’ Wolf, and Bo Diddley, Buster Brown … Anyway, every time Jimmy would come through, he’d be doing this run going on up through Oklahoma. And he never carried a band with him. Every once in a while he had a one-eyed bass player who was kind of his manager, too, but he didn’t show up except for maybe one or two times; I just remember him because he was a one-eyed bass player, which is probably a horrible way to remember somebody, but you don’t forget that, either! Anyway, we’d go up there and play with him a lot. And I remember another night we went up there with Sonny Boy Williamson. In fact the first joint I ever smoked in my life was in the men’s room of this black barbecue joint in Lawton, Oklahoma.

You were barely out of your teens, early 20s at most, when you were playing with those guys, all of whom must have been heroes to you …

McClinton: Oh they were, absoluely!

So was it hard not to lose your shit being onstage with them? Or by that point were you already like, “We’re all musicians here, just doing our job …”?

McClinton: Well, you have to put it into perspective. That was still during segregation; I mean, it was breaking apart, but it was still going on. But we worshipped those guys, you know? We wanted to play blues. And Jimmy Reed to me is still one of the greatest genius musicians and lyricists there ever was. And you’ve got to dig for them, but you can hear some recordings of his performances when he was so drunk and was pitiful, but he still maintained his ability to …

Hendricks: Tell the story about how excited you were to get that new microphone for Jimmy Reed that one time …

McClinton: Well, I was, but I wanted to get it for me as much as I wanted to get it for him. But yeah, we were backing Jimmy Reed back in he early ’60s, and I didn’t have a pot to piss in. I worked jobs a smart monkey could do and played for barmaids. But there was this microphone, a big Shure microphone — the one people use in videos nowadays, it’s very retro, looks like a fist. I had it in layaway. Remember layaway? Well I had it in layaway, and we were going to be playing with Jimmy Reed this one weekend, and I scraped up the last $10 or $12 or $13, whatever it was, I got it together and got that microphone out, and I had it set up on the stage for Jimmy Reed. And he’d always do two shows, and by the second show he was usually so drunk that he’d sit down. And he went out there and sat down for the second show, and before he ever sang a word, he shot about a quart of gin out of his mouth and into his microphone, just soaking all those crystals and little things — I can still see it in slow motion. It was like the big bang. It just went everywhere. But I’ve still got that microphone — and the bag it came in, too.

Hendricks: I’ve held that microphone!

Did you ever use it again or was it ruined?

McClinton: I’m sure I probably did use it again, but I don’t recall. But I do remember that I cleaned that thing with a toothbrush and Clorox for weeks. When I first started playing, the only microphone I had was one with a felt cord on it, and it came off a tape recorder. And that was all I had for a microphone. And P.A.s weren’t available. P.A.s back then were two 12 inch speakers that you clipped together with the brain inside and one input. And we had to use violin pickups on an upright piano: two of them, one wedged in one end and one wedged in the other, and ran them through an amp. Fucking great!

Hendricks: But don’t you think that having to play through that kind of equipment had something to do with developing that unique sound that you have singing? Because you can cut through anything when you sing — you can always hear the lyrics in your songs. I would think a lot of that had to come from you having to cut your teeth on such crummy sound systems.

McClinton: Well, you’ve got to cut through and you’ve got to be heard, and you’ve got to make them like you. But the bottom line is, it doesn’t matter what kind of equipment you’ve got; if you can do it, you can do it with anything.

Considering how formative your years playing the Jacksboro Highway were, both with your own band and backing up all those blues giants, it’s almost a shame that that part of your history always seems overshadowed by that one time you met the Beatles and John Lennon. I mean I can’t imagine meeting them at that time in your life came close to what it meant to be onstage with Jimmy and Sonny Boy and Howlin’ Wolf.

McClinton: Well, it didn’t, but it was very important in another way. Before that, I had never really even been out of Texas, and I got on a plane and flew to London! That was a really big deal for me. I mean, all the fantasies in my head about ancient England and kings and knights and Robin Hood and rain and drizzle and World War I and World War II … all of that stuff were things that I had such great interest in. So when I got over there, we were flying in the sunshine, and when we got over London we descended into clouds, and by the time we landed it was perfect drizzle. I felt like it was done especially for me! And it was thrilling, thrilling time. So again, you have to put it into perspective: This was the very early days of rock ’n’ roll, and people weren’t jetting across the world every day, it just wasn’t happening. So to go to England was a big deal. As for meeting the Beetles over there … we were all on common ground at that point; we were the same age, we had the same dreams, we were going to do the same things and on and on and on. And it wasn’t until after I’d been back from over there, maybe a year before the Beatles broke it wide open, that John mentioned to somebody in an interview that he was encouraged by the harmonica on “Hey Baby.” So that has grown into … it’s been romanticized now to the point where I taught him everything he knew.

You’re supposed to just run with that, Delbert!

McClinton: [Laughs]

Hendricks: Well, the thing about Delbert is, he’s incredibly honest, and that can be a bit of a challenge when you’re trying to tell a good story …

McClinton: But that’s still a pretty good story without embellishing it!

Hendricks: My favorite part of that story is, on a night that they were off, here’s this kid from Fort Worth, and John and one of his friends came by and picked Delbert up and took him out. I think that’s more fun than harmonica lessons.

McClinton: Yeah, they took me out for a night on the town in London, and I know my mouth must have hung open the whole night. Because I saw things you just didn’t see in Fort Worth, Texas. The beatnik joints were everywhere: dark places with people doing … dark things. [Laughs] It was mind blowing. I felt like, “Good god, I don’t know dick about what’s going on!” But it was eye opening for me. And being there with Bruce … that was the thing that was so, so much fun. I’ll never forget, in the London hotel room one morning — we stayed in the same room. And Bruce got up and he went to the bathroom and he walked back and looked at himself in the mirror, and he turned around and looked at me and said, “Do you think I look like a rock ’n’ roll star?” He’s just as cornbread and gravy as they get. [Laughs]

Delbert, are you nostalgic by nature? Not just for the good times, but like … when you revisit your time out West, right before you wrote “Two More Bottles of Wine” and were staying in that cabin in Laurel Canyon with the sewage all over the floor from the septic tank … are you like, “Ah, California!” Or is it more like, “Jesus, I can’t believe I put myself through that …”?

McClinton: No, no … I never felt like “why did I do that.” It was all an adventure. And we were so hungry that you couldn’t stop us. You just couldn’t stop us. Everything was, if it was too big or too wide, you crawled over it, and if it was too tall, you went around it. That’s pretty much the way we lived, day to day. And it was great. I was never more thrilled in my life than when I was really hungry for some kind of success.

The times when you finally really started experiencing some kind of success had to have been pretty thrilling, too. One scene you were a part of that’s always fascinated me as a Texas music fan is the late ’70s/early ’80s heyday of the Lone Star Cafe in New York City. That place was long gone by the time I lived in New York in the ’90s, but just like the Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, there’s something almost mythical about the stories about it.

McClinton: That’s because it was! It was a mythical place. It was because of … it was all because of Willie. Willie started that whole thing; he and Waylon and a few others, but basically it was Willie that started a whole new revolution in music. Like the early Willie picnics. They meant so much to me and others because we were the ones who got all the perks. So it became Willie’s family, and his family grew into millions of people, and the Lone Star Cafe grew out of that and if you were from Texas, and you played the Lone Star, you were some kind of a god. That was the perception because everybody played into it, and it was fun. Everybody put on a hat, bought some food, and went “yee-hah!” And bought us all shots and beer …. Lone Star beer! Willie always had a busload of Lone Star beer, just cases of and cases of it, because they sponsored him, and Lone Star became a very big beer because of that. But really, anything “Lone Star” was big at the time, because Texas was everywhere and Texas was it. And the Lone Star Cafe in New York was a place where anybody could go and feel like a Texan.

Delbert McClinton and Willie Nelson, givin’ it up for your love back in the day. (Photo by Watt Casey)

Hendricks: Cleve Hattersley, who was the manager of the Lone Star for so long, said that they got their pick of the litter as far as anybody they wanted to play there. But everybody came out when Delbert played. John Belushi and Dan Ackroyd and Bette Midler and Elvis Costello, Jimmy Buffett, Joe Ely … everybody came out on the nights that Delbert played, and it was always a VIP night. They didn’t have room for regular customers, because everybody wanted to come on those nights. I thought that was really cool to hear.

McClinton: The funny thing about the Lone Star was it was the most unlikely place to have a venue. Because the bandstand was just about four feet from the bar, and from the stage you looked right straight into the bar. And the place was very narrow so if you were in the back of the bar, you never even saw the band. But the thing that was so magic about it was that whole room full of people walked into the place right in front of the bandstand. Everybody was right on top of you.

Since he was living in New York when the Lone Star took off, did John Lennon ever go to any of your shows there? Or did you ever see or talk to him again after that first meeting in London?

McClinton: No. I never saw him again.

That really is a shame. But Diana, speaking of talking to Cleve … what was your process for interviewing all the people you talked to for this book? I lost count of all your sources, but it’s a pretty big cast. Did you go to a lot of them before talking to Delbert, or did you chase most of them down after you’d already talked to him?

Hendricks: Well, the first thing I did was the outline … Or actually, the first thing was this piece on Delbert I wrote for the Journal of Texas Music History, which is the publication for the Institute of Texas Music History at Texas State. And when Texas A&M was interested in doing the book, I knew that I wanted to expand on it. And I had actually already talked to a lot of people for that Journal piece, including Glen Clark and Don Imus. But every time I’d talk to somebody they’d say, “You know who else you need to talk to, is …” So it became this chain, where Glen Clark gave me T Bone Burnett’s phone number, and then T Bone said, “You know you really oughta talk to Don Was, too.” And on and on. And every person that I talked to, from Delbert’s first manager to Bonnie Raitt, they just couldn’t stop talking about their memories. It was really a lot of fun.

One thing that I have found, and in this business you don’t see it often, is Delbert has friends today that were his friends 65 years ago, that were his friends when he was 13 years old, that were his friends when he was a kid. And they still go on the cruise! I mean, Bruce Channel is on the cruise every year. And you don’t see a lot of people in this business who maintain friendships that long. But when I talked to musicians who’ve remained friends with him, even been fired by him, every one of them said, “If he called me, I’d be back.” There were several people that you fired several times. I think Ernie Durawa’s one of them. I think you wore out a lot of drummers.

McClinton: Oh I’ve been through more drummers than anybody in the world. I wasn’t trying to be an asshole, I was just trying to find the right one! Poor Ernie … I had him slamming the drums so hard that at the end of each night, his hands would just be raw. He spent half his time on the bus just putting New Skin over his raw hands.

Delbert, was there any chapter, figuratively or literally, that you were hesitant to really delve into for this book? Or Diana, that you were dreading have to write about?

McClinton: Yes, there was. But I found a way to include it without getting specific.

Hendricks: I would say that probably the hardest part for me to include was the heartbreak that Delbert and Wendy went through when they were trying to have a child. They’ve got wonderful kids now, but they just had so many struggles on that front in the beginning, and they both wrote about it all through that time in their own journals. So that was really hard both to read and write about, because you would see the excitement of the fact that they were expecting a baby, and then the heartbreak … I think that was the hardest part to cover for me.

McClinton: Well, that’s always the hardest part.

Hendricks: And I think it was also kind of hard for Delbert to kind of explain his failures. I think he had a lot of struggle with that, and he took all the blame for any failure that he ever had. And I would go, “Well somebody told me this,” and he would say, “Well, but you know, It was still my fault.” Whether it was a relationship, marriage, family issues, he would say, “I’m going to take [the blame for] that one.” Now, as we were going through the book and I was reading parts back to him, just fact checking and making sure the timelines were right, every now and then he’d say, “I don’t know if I want to put that in there.” And most of the time I would say, “But I think it needs to stay,” and it would … but there were a couple of times where I decided it was not a hill I was going to die on, and I let it go. But the story is the story, and you can’t have American dreams without some struggles, challenges, and heartaches along the way.

Diana, what for you was the biggest surprise for you in talking to Delbert where you were like, “Wait, you did/saw what??”

Hendricks: There were a lot of those “say what” again moments. In fact, when I was finishing the book, just going back and fact checking things, Delbert would casually mention things like, “Did I mention to you that up until two weeks before the murder, my wife and Clay and I were living at the Priscilla Davis mansion?” I mean, that was the biggest murder case ever in Texas, with Priscilla’s husband, T. Cullen Davis being charged with conspiracy to murder. And I said, “Um, no, you didn’t mention that, but I’d definitely like to put it in the book.” And there were several of those moments. Like Delbert seeing John Kennedy mere hours before he was assassinated.

McClinton: It was no more than an hour …

Hendricks: And having the FBI come in and question Delbert because his phone number was in Jack Ruby’s calendar. So yeah … there were so many of those encounters that were just part of his life where he’d just be like, “Did I ever tell you about …” and I would just kind of be stunned and pull out my pencil and paper and say, “Wait, wait, start over!” But still, some of his best stories were the ones about just everyday, simple things he’d remember. I think one of my favorites is when you and your cousin were out in the backyard, and your uncle heard you singing … That’s probably the first time that anybody recognized that you were going to be a singer.

McClinton: That was the summer of ’51, after we moved from Lubbock to Fort Worth. I went and spent two weeks with my favorite cousin, Walter, in Sweetwater, Texas. And Walter’s dad, my uncle Earle, he was somebody you always wanted to give a wide berth to, because he was mean when he drank and he always drank. But Walter and I were out in the backyard one day and I was singing “Hey Joe,” the old Carl Smith song, and the screen door opened, slammed against the house, and my Uncle Earle came out saying, “Who’s that singing?” I said “It was me.” He said, “Boy, that’s good, that’s real good.” And the two weeks I was there, he was a completely totally changed man.

Music tamed the beast.

McClinton: [Laughs] He drove a milk delivery truck, and he would pay us 50 cents a day to go with him early in the morning out to the milk factory, fill the truck up with milk for the route, and then we’d go to this coffee shop and have coffee and donuts. And Uncle Earle would have me up there singing on the counter of the coffee shop at 3:30 in the morning for all the milk men. And that was the first time I thought I might be on to something.

And at the risk of spoiling the “ending” of the book for anyone, 67 years later, you’re still at it! Your last record, Prick of the Litter, is a year old now. You put that one out on your label, Hot Shot Records. How many more albums do you think you have in you?

McClinton: Oh man, I don’t know. How am I supposed to answer that? But I’ve already got one and a half down …

Well let me put it another way. What gets you back into the studio these days? Is it an itch, is it a pull … or is it a push from Wendy? When do you know it’s time to go back in?

McClinton: When I’ve got a sackful of songs. And I do. In fact, we’ve already cut tracks on a lot of them.

I remember that last album being pitched as a almost sort of a jazz or crooner record, which is how I heard it the first few times I played it. Like, “Well this is a lot different from anything I’ve heard this guy do before.” But I revisited it again last night, and I was really struck by how above all else, it just sounded like a really good Delbert record to me. And it wasn’t like it had to grow on me or I got used to it over time, but rather that after the paint kinda dried, it just became more obvious how it just fits right into the big picture of your sound. So to make that a question — when you were recording it, did it ever actually feel like a different direction at all to you? Or is it always just, “This is what I do”?

McClinton: Well, the main reason that that record really came about is, unfortunately, I’m not much of a guitar player. But the band that I’ve worked with for the last five years, they’re as close to me as anybody can be, and the guitar player, Bob Britt? He knows all the chords. And when we sat down trying to write together, it was like magic. It was absolutely like somebody had opened up some magic that I got to be a part of. Because he anticipates me and I anticipate what he’s going to play, and we have written a shitload of songs in the last two years. Good songs. And a lot of them are all the good songs that are on Prick of the Litter, but I’ve got some more that we’ve just done that are going to be even better. Really cool stuff. One song is one minute long. And that’s all it needs, one minute.

That line in “Pulling the Strings,” “I’m goin’ nowhere, but I’m makin’ good time,” is still one of my favorites of the whole year.

McClinton: Well good. I like that line. That was one of the first songs that Bob and I wrote when we sat down. It was me and Bob and Mike Joyce, the guy who plays bass with me. We all got together one Wednesday and we wrote that song and one other one in a matter of two and a half hours. So we did it again the next Wednesday and we wrote two more, and then we went down to my place in Mexico and wrote about four more. So now we’re going back in January to write eight or nine more — right after the cruise.

This will be the 24th annual Sandy Beaches Cruise. Diana, you could almost write a book on the history of that enterprise alone. But this will only be your second time, right?

Hendricks: Yes. I didn’t get to go last year.

I got to do it 15 years ago and still have good memories. What did you like most about your first trip in 2016?

Hendricks: I’ve got to say, probably one of the things that resonates with me now is, we got off the cruise ship, we went to the airport, I think in Tampa, and it was chaos at the airport, except for everybody that was carrying a Delbert McClinton cruise bag just automatically grew together. So all of a sudden you look and there’s this whole group of people with these brightly colored Delbert McClinton swag bags, and they’re family. These were people that didn’t know each other before — they’re leaving Tampa to go back home to Europe, Alaska, Texas, New York — but after one week, they were family. And that’s what I got from the first cruise I went on. You get on that cruise, and you leave and you’re not the same. You have a family that is there that you really have this simpatico connection with.

McClinton: It’s therapy. There are no assholes on my boat. None. There’s no room to be an asshole on my boat. It’s just a bunch of friends.

Hendricks: And sometimes it’s friends who don’t know each other, but by the time they leave it’s like the best summer camp that an 11 year old can go to. Because you can’t wait to come back. And the last night when the last concert is going and everybody’s onstage and everybody in the audience is singing along, you’re like, “I don’t want this to end!” There are so many magical moments on the cruise that really bring people together. And all the musicians on the cruise are getting a vacation as well, because a lot of times they don’t get that opportunity to just play with friends. And in this case they do. So you’ll see Raul Malo get up and sing with Red Young in the piano bar late at night, and you’ll see Marcia Ball go play with Delbert. You just see everybody getting to play together, and I’ve just never seen so many happy faces. And Delbert, he probably works harder than anybody else on the cruise, because not only do all the musicians want to hang out with him, but everybody on the cruise does. But he does a great job of making sure everybody feels special, because he knows they helped him get here.

What ports will the ship be going to this year?

McClinton: [Laughs] I don’t even know, man. I haven’t been off the boat to go onto any of these islands in the last seven or eight years! Because you get off the boat, and it’s people trying to sell you worthless shit everywhere you look. If I never see another silver chain, it’ll be too soon. I mean, the islands are nice, but you know, I’ve been there. So now I prefer just kicking back and looking at them from the ship and making my own little fantasies about them. They’re more romantic that way.

McClinton: [Laughs] I don’t even know, man. I haven’t been off the boat to go onto any of these islands in the last seven or eight years! Because you get off the boat, and it’s people trying to sell you worthless shit everywhere you look. If I never see another silver chain, it’ll be too soon. I mean, the islands are nice, but you know, I’ve been there. So now I prefer just kicking back and looking at them from the ship and making my own little fantasies about them. They’re more romantic that way.

Hendricks: He’s right. In fact, the picture on the cover of Prick of the Litter is a self-portrait that Delbert took of his own socks from the cruise ship. That’s kind of the illustration of what it feels like.

McClinton: I had just finished a show and went back to my cabin, walked out on the patio, sat down, just kind of chilling. Had those red socks on, first time I’d ever had them on in my life. And I looked at them and thought, “That’s a good picture.” And I took that picture. I just thought, “Any prick would wear those socks!” Any kind of prick.

No Comment