The author, Diana Finlay Hendricks (Photo by Kim Porterfield)

Editor’s Note: LoneStarMusicMagazine.com is proud to feature the following excerpt from the new book, “Delbert McClinton: One of the Fortunate Few,” by San Marcos, Texas author Diana Finlay Hendricks. Officially in stores on Dec. 12 (but already available through online retailers and direct from the publisher, Texas A&M University Press), Hendricks’ book chronicles the Grammy winning legendary Texan’s life and career from his Lubbock origins to his rise to fame on the progressive country and blues scenes in the ’70s and ’80s to his 21st century resurgence as one of Americana music’s most revered elder statesman. The chapter excerpted here picks up the story back in 1970, when McClinton, by then already a well-seasoned (and more than a little jaded) veteran of Fort Worth’s notorious Jacksboro Highway nightclub scene, decided to follow the lead of his buddy Glen Clark (later of Delbert and Glen fame) and head out west for Los Angeles to test his luck in the promised land of free spirits and Topanga cowboys.

***

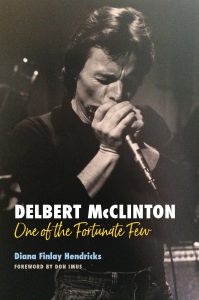

“Delbert McClinton: One of the Fortunate Few”

By Diana Finlay Hendricks

Texas A&M University Press

CHAPTER 8

“Two More Bottles of Wine”

Maggie came to town, and we were a bright shining light for a few weeks in Fort Worth. But, I still wasn’t getting anywhere. I was thirty years old, and I wanted out of everything — and most of all, out of Fort Worth. Glen [Clark] and Ray [Clark] were writing and telling me how great Los Angeles was. Maggie had a Chrysler Imperial, a sack full of cash from her divorce settlement, and a sense of adventure. So, we loaded up and drove nonstop to Topanga Canyon. —DELBERT McCLINTON

It was late winter of 1970 when they loaded the car. Driving to California brought Delbert a sense of freedom he had never experienced. Although it would be a difficult time for him personally, it also was a productive time in terms of evolving as a songwriter and performer. Delbert’s move to the West Coast was encouraged by his longtime friend and musical partner, Glen Clark, another Fort Worth musician who had played keyboard off and on in Delbert’s bands for years. Glen made the move to Los Angeles in 1969, and wrote several letters encouraging Delbert to head west and join him.

Glen’s father was a song leader in a Fort Worth area Church of Christ congregation. Music had a constant presence in the Clark household. Everyone in the family played piano and sang, and Glen was somewhat of a child prodigy. He successfully auditioned for the Texas Boys Choir when he was ten years old and within weeks, he was touring with the group. “It was a pretty big deal at the time,” Glen says.

However, he believes his greatest early influence happened outside of church and the regimented music studies of the Texas Boys Choir. Glen was about seven years old when he first heard secular music being performed live, and there was no turning back.

Glen was spending the night with his friend, Vaughn Clark (no relation). Vaughn’s father had been a drummer for Lawrence Welk and had long cultivated an interest in music among his children. Vaughn’s fifteen-year-old brother, Ray Clark, was playing drums in a band with some of his high school friends. Delbert McClinton was the bandleader.

“Delbert was already rocking. Man, I wanted to be just like that guy,” Glen recalls. “I did everything I could to learn that kind of music. My parents encouraged me in a proper way, with music lessons and voice training. But the Texas Boys Choir was a little too regimented,” he admits. “I got out of it pretty quick. Here I was singing Latin masses with the Texas Boys Choir. I discovered black radio stations and country radio stations, and I hear high school kids, that I know personally, playing this great stuff that made my hair stand up on end. I went to my classical piano teacher and asked her to teach me that. She just couldn’t teach me to play with soul. So, I made the switch from classical to rock and blues and country.”

Glen started performing in bands regularly at the age of sixteen, playing piano with the popular Bobby Crown and the Capers, a blues and R&B group in Fort Worth. Bobby Crown, McClinton, and Bruce Channel all were inspired by that same Texas blues shuffle that became an integral part of what some were calling the Fort Worth sound.

Glen says, “Everyone wanted to do that music, but Delbert made it his own. Even back then, he had his own spin on the music. He respected the styles, learned from them, and built on them. Delbert has always been a master of that. He can take a combination of sounds from different bands and styles and make it his own. He has always kept that edge that made you know you were listening to something you wouldn’t forget.”

Glen started performing on keyboards regularly with McClinton in 1968, playing a few regular gigs and an after-hours weekly show at Fort Worth’s Colonial Club, near the General Motors plant. “It was plain awful. We thought it was going to be great, because the show started at 2:00 a.m. We figured that we could play our original music and kick back and just get in the groove, but the factory shift workers would get off work about that time and come in and want to be rowdy and drink and listen to Top 40 country. I think it was probably one of the roughest regular gigs Delbert and I ever played, and that’s saying a lot. That was the last band Delbert and I were in together in Texas. We called ourselves the Losers,” Glen recalls.

Glen finished high school and went to the University of North Texas (North Texas State University at the time) to continue his education. “I got busted for pot in Denton. The cop felt sorry for me, and the charges were dismissed, but it was reported to the dean. It was mid-semester. The dean called me in and said, ‘Son, you have to come into my office once a month and verify that you are not smoking pot.’ I said, ‘I don’t think I will be able to do that, sir. But I appreciate your offer.’”

Glen loaded his Volkswagen bus with a chest of drawers from his mother’s house with all of his clothes in it, a Hammond C3 organ, twenty dollars, and a plan.

Glen moved to Los Angeles in 1969. “I was wanting to do original music. Around Fort Worth and Denton, everyone wanted to hear the songs they heard on the radio. Top 40 hits. Our friend, Ray Clark (Delbert’s former drummer), had moved out to Topanga Canyon, and had been writing to me. Back then, you didn’t call on the phone. You wrote letters.”

Glen says, “Ray had been out there for several years. When I went out there, he had a place for me to stay. He had been writing to me for a while, telling me that it was where I needed to be if I was serious about music. I had been trying to write songs and playing in North Texas where no one wanted to hear original music. Ray said, ‘They’ll love your original stuff out here,’ and he was right. The climate was different. They wanted to hear original music. Playing music was like performing a play, with people coming out to really listen to what you were singing. It was a great place to be.”

Ray had been on the road with Arlin Harmon and the Big Beats, and was tired of traveling. He had moved into a cabin in Topanga Canyon in Western Los Angeles County.

Topanga Canyon had become a magnet for free spirits, counter culture, and original artists. Wallace Berman, who has been credited as the father of assemblage art, had attained comfortable success by this time, and opened his Topanga Canyon home to an array of artists and musicians who needed a place to develop their art. Neil Young lived in Topanga and would record most of his After the Gold Rush album in his home basement studio in 1970. Topanga Canyon property was easy to come by and rent was dirt cheap.

Drugs played a big part in the culture of the West Coast at the time. The criminal element was far different from the gamblers and gangsters of Fort Worth. Charles Manson was building his “family” at the Spahn Movie Ranch, not far from Topanga Canyon, where he had briefly befriended both Neil Young and Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys.

California had beckoned Texas songwriters and musicians for decades. If New York was the traditional home to the American music industry, and Nashville had come into its own as the country capital, Los Angeles welcomed the contemporary artists, undiscovered actors, original musicians, and creative writers with little money and big dreams.

Bill Mack says, “Bob Wills finally became a national success when he left Texas for the West Coast. The Bakersfield Sound, created by Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, as a reaction to the sophisticated string-orchestra sounds coming out of Nashville, was taking country music by a storm.”

San Antonio’s Doug Sahm, who had risen to international fame with the Sir Douglas Quintet under the direction of Houston’s Huey Meaux, had made the trek west in 1965, after a marijuana bust in Texas. He settled his family in the Salinas Valley as soon as his probation officer assured him that he would not be reported as a fugitive from Texas. Several of his band members went with him, but his best friend, Augie Meyers, didn’t catch up with the band until 1969. Augie admitted that he couldn’t go at first because his probation officer would not let him leave Texas. He told Sahm biographer Jan Reid, “I was married and had a family myself, a boy in school. But, one day, Clay came home and said their new teacher used to be a policeman. They asked him what he ever did, who he had put in jail, and he said, ‘Well, I helped arrest the Sir Douglas Quintet.’”

Augie managed to fulfill his legal obligations to the State of Texas, and move his family out to the West Coast, joining Doug in the San Francisco scene, trading their British-style suits and Beatle boots for more comfortable Texas cowboy boots and hats.

This new West Coast music scene was becoming heavily populated with talented Texas expatriate songwriters and musicians, looking for a place to hone their art into success.

Glen adds, “The climate was so different. People wanted to hear original music. I only had about four or five original songs good enough to play when I got there, but I played them a lot and wrote some more. Delbert was going through a hard time back in Fort Worth. I wrote him a letter and told him to come on out. We had a place for him to stay. I forgot to mention that housekeeping was not a priority.”

Delbert was still playing around Fort Worth, and had taken up with Maggie. His divorce was pending, and Sue was so angry. He was not getting time to spend with his son, Monty, anyway, so he decided that this might be a good move, professionally and mentally.

The early 1970s were prime time for living on love and cheap beer. Hippies were coming into their own. The counterculture was booming everywhere, but the West Coast was ground zero.

The Los Angles music scene was developing its own voice and growing into a strong country-folk-rock movement. This rhythm and blues and country influence on rock focused on the songwriter and the lyrics. Gram Parsons and the Byrds, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and Pure Prairie League were adding steel guitars and fiddles to rock and rhythm and blues mixes. The scene was open to new and experimental sounds and was a good fit for artists like Delbert seeking to create new sounds.

Delbert and Maggie piled what they could carry in the back of her car and headed west together. They moved in with Glen Clark and Ray Clark and Ray’s girlfriend, Monique. As Delbert describes it, “And just like that, we became hippies.”

“The night we got there, after driving straight through from Fort Worth, we were hot and tired and sweaty. Ray came down the hill and led us up to the house. He had long curly hair below his shoulders. He and his girlfriend lived in this cabin with a dirt floor, on the side of the mountain. We wanted to take showers. Ray said something about being careful with the water because of the septic tank or something. And we said, ‘Okay, yeah.’ Ray had set Maggie and me up with a mattress on the floor of this room with a dirt floor. I got up in the middle of the night to go pee and the floor all around the mattress is flooded — soaking, fucking wet, and stinks with raw sewage,” he adds.

“We had a Fort Worth guitar player friend of mine and his girlfriend who had just wanted to ride out there with us, and Maggie and me, and we had all come in and taken showers and no one listened to Ray talking about the possibility of the old septic tank overflowing. Maggie and I were sleeping in that shit. Crazy. But we were, well, I wasn’t that young, but I was young enough, and I was hungry. So hungry to do something. And I knew that if I worked hard enough, I’d get something to eat. It was okay, the way we lived. It was an adventure.”

Glen adds, “Southern California really was a different world for Delbert and me. Everyone was smoking pot and doing some kind of drugs. There was this whole open sex scene going on. It was just the way it was. Ray was working, and got us that job at the veterinary supply warehouse. We rode to work with him every day. His wife didn’t do anything. Monique stayed home. The deal at Ray’s was that we would all work and Monique would stay home and take care of the house and cook. She talked about being friends with some of the Manson girls, but I don’t know. Everybody kind of knew everybody else in the Canyon. She sure didn’t clean house. That was the filthiest place you ever saw. She wasn’t much of a cook either, but we didn’t expect much.”

After a few weeks of living with Ray and his girlfriend, Glen, Delbert, and Maggie rented their own apartment together. Delbert remembers: “We got this place in Venice, with a bedroom and middle room with a mattress on the floor and a kitchen and a bathroom. The whole place was painted black — floor, ceiling, sink, everything — and it had four locks on the front door. I don’t remember the real name of the apartments, but they were better known as ‘Methedrine Manor.’ The only thing that came through the windows were the police lights on the street every night. They’d fill the room with red and blue light.

“Glen and I were working with Ray at a veterinary supply warehouse in West L.A. A lot of days I’d be sweeping out my corner of the warehouse, wondering, what the hell I was doing here. We were hungry, but, man, we were living the dream, or working toward it.”

Delbert’s relationship with Maggie did not last long. The West Coast quickly lost its gleam for her. The day she left, Delbert was heartbroken. He sat on the mattress in that dank, black apartment and wrote a song about sweeping out a warehouse in West Los Angeles. In 1978, “Two More Bottles of Wine” became a number 1 hit on the country charts for singer Emmylou Harris and marked a major milestone in Delbert’s evolution as a songwriter.

We came out west together with a common desire

The fever we had might’a set the West Coast on fire

Two months later got a troublin’ mind

’Cause Maggie moved out and left me behind

But it’s all right ’cause it’s midnight and I got two more bottles of wine.

Well, the way she left sure turned my head around

Seemed like overnight she just up and put me down

Ain’t gonna let it bother me today

’Cause I’ve been workin’ and I’m too tired anyway

But it’s all right ’cause it’s midnight and I got two more bottles of wine.

Well, I’m sixteen-hundred miles from the people I know

I’ve been doin’ all I can but opportunity sure comes slow

Thought I’d be a big star by today

But I’ve been sweepin’ out a warehouse in West L.A.

But it’s all right ’cause it’s midnight and I got two more bottles of wine

Yes, it’s all right ’cause it’s midnight and I got two more bottles

Delbert says, “Emmylou cut that song in 1978, I didn’t even know until someone called and told me about it. I don’t think I ever made any money off of that cut because I was pretty much fucked out of all of the publishing back then. I didn’t know any better.”

Less than ten years after writing those lines, Delbert talked to journalist Gary Cartwright for an interview in Rolling Stone magazine. Delbert recalled that he felt better after the song was finished. “‘I’d hate to think I have to suffer like that every time I wrote a song,’” he said. “‘I don’t ever want to be that depressed again, but I want to be an interpreter of those feelings . . . a teller of the things I’ve done, not the things I do.’”

I enjoyed reading this article. Delbert became a big part of my music life in 1990, where I saw him at a night spot in Little Rock, Arkansas. I love his music and his sense of humor. His music has helped me through some low times in the last 31 years. I will always love Delbert.

I loved this story on Delbert