By Michael Corcoran

Owner Don Robey had the muscle and the money, but business manager Evelyn Johnson was the brains and the backbone behind the Duke/Peacock music business empire of the ’50s and ’60s. Ten years before Berry Gordy started Motown, Houston had the hottest black music label in the country, in both the R&B and gospel fields, and Johnson ran day-to-day operations at not only Duke/Peacock, but the recording studio and booking agency (Buffalo Booking) at the same Erastus Street address in the Fifth Ward. Musicians nicknamed her “Mother Superior,” as Johnson ruled her fiefdom with savvy and personality for more than 25 years, making her one of the first powerful and respected women in the music business.

Johnson passed away in 2005 at age 85. She was never married and had no biological children, but the feisty and funny Louisiana native raised a whole bunch of blues musicians and gospel singers. She taught Bobby “Blue” Bland how to read and was always just a phone call away from any artist in need.

A former numbers runner, Robey was rumored to be mob-connected and dealt with adversarial situations accordingly. He claimed ownership of more than 1,200 songs he didn’t write and many is the story of Robey using a gun as a negotiating tool — as when he allegedly stole “Treat Her Right” by Roy Head from producer Huey Meaux. But Johnson balanced it out with her matronly wisdom and care. They were quite a team, from 1947, when Johnson was initially hired to work at Robey’s record store on Lyons Avenue, until 1973, when Robey sold off the company to ABC/Dunhill.

“Maybe he ripped me off,” Robey’s first client Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown told me in 2004, “but if it wasn’t for Don Robey nobody would’ve known about me.” Much impressarial greed was built on such sentiments in the years after WWII.

They hit it harder at Peacock, which first became widely known for church-wrecking gospel, boasting top shouters Archie Brownlee of the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi and Julius Cheeks of the Sensational Nightingales, in addition to the Dixie Hummingbirds, Pilgrim Jubilee Singers, and Mighty Clouds of Joy. Robey brought the bass drum to gospel and sold half a million copies of “Let’s Talk About Jesus” by Austin’s Bells of Joy in 1951.

Johnson ran things from the office on Lyons Avenue until 1953, when Robey’s Bronze Peacock nightclub closed and the whole company moved into the building. Before 1956, when a full studio was built at 2809 Erastus, Robey and musical directors Joe Scott and Dave Clark used Bill Holford’s ACA (Audio Company of America) studio on Westheimer. Anybody who thought blues and gospel didn’t mix never saw the lobby of ACA, where Big Walter “the Thunderbird” Price or Marie Adams might be arriving for their sessions while the Spirit of Memphis or Sister Jessie Mae Renfro would be wrapping up theirs.

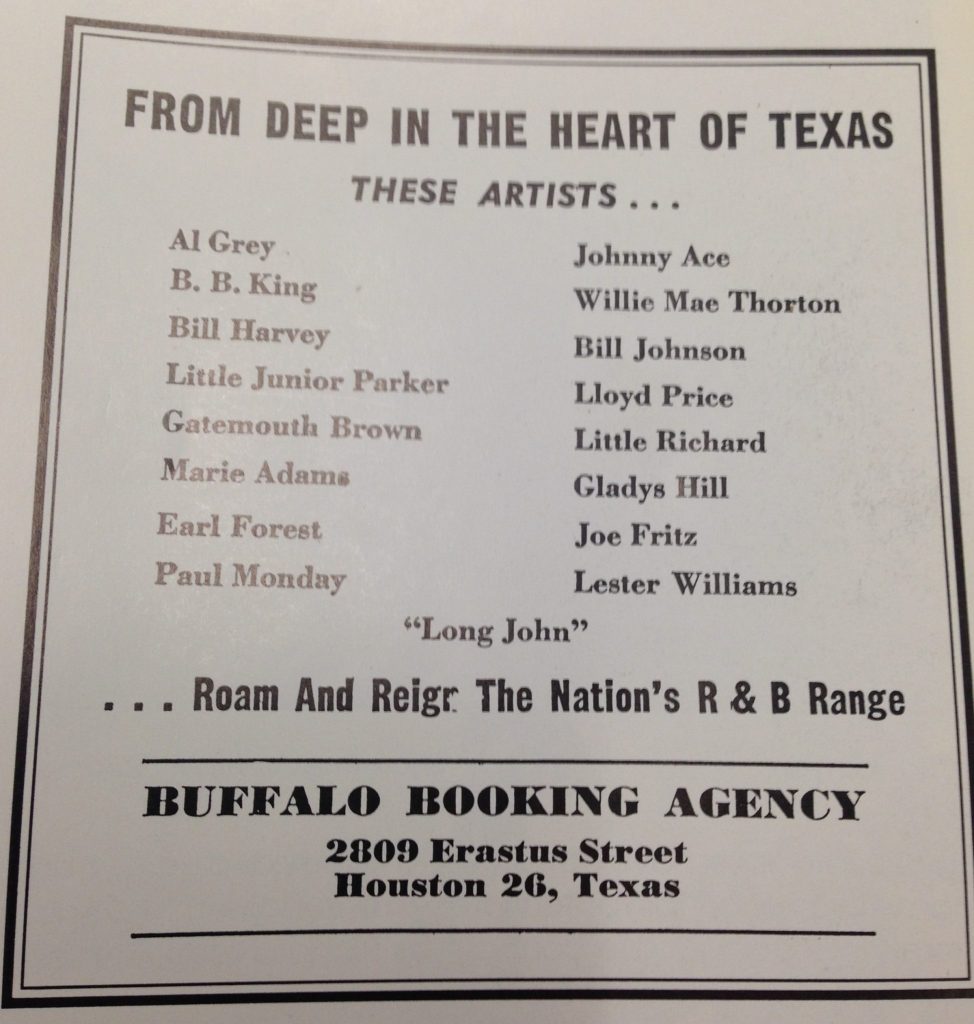

When Robey acquired Memphis label Duke and its roster of Bobby “Blue” Bland, Johnny Ace, Junior Parker, Roscoe Gordon, Memphis Slim and more in late 1952, Houston built a pipeline to Memphis to become THE hub of gritty black music. B.B. King was signed to Buffalo Booking for nine years, strengthening the connection. The Duke/Peacock sound was what you got when Memphis singers were backed by Texas session players (Pete Mayes, Grady Gaines, Clarence Holliman, Calvin Owens, etc.), though the label’s first big smash, “Hound Dog” by Big Mama Thornton in 1953, was recorded in California with Johnny Otis’ band.

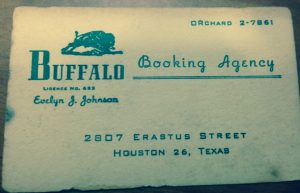

Motown’s philosophy was to sell black music to both black and white kids, but Duke/Peacock was going right for the African-American club market. As Stax/Volt would later define Memphis grit, Duke/Peacock was raw, black Southern music for an audience more into getting down than fitting in. With Buffalo Booking (which listed Johnson as owner), Johnson helped carve out not only the so-called “chitlin circuit” of nightclubs in Texas and Oklahoma, but the “gospel highway” of touring religious groups.

“Evelyn Johnson is a remarkable lady, one of the great women of her time,” B.B. King told Alan Govenar in his 1995 book Meeting the Blues. “I don’t think she gets enough recognition because to me she was one of the pioneers.”

Considering the scope of her influence, it’s interesting to note that Evelyn Johnson, born to a Creole family in 1920 in Thibodeaux, Louisiana, had no intention of pursuing a music business career while attending the Houston College for Negroes (later Texas Southern University). Johnson set out for work in the medical field, getting a job as an X-ray tech at Houston Memorial after graduation. But after she got sick from exposure to radiation, Johnson was put on leave and never went back. She took business courses and found herself keeping books at the Bronze Peacock, one of the fanciest black nightclubs in the South.

Johnson quickly became the person Robey could count on, so as he was coming home from a night of gambling in the back rooms at the Peacock, Johnson was getting up and going to work. There have been rumors that the pair had a romantic relationship and even lived together in the late ’50s, between Robey’s marriages, but the only two people who know for sure are gone. Robey died of a heart attack in 1975 at age 71.

We do know that great success came from their working relationship. Neither could’ve done it without the other. Robey would have a grand idea and Johnson would take the steps to put it into action: that’s how Peacock Records started. Robey felt as if he’d found the next T-Bone Walker when he signed the Orange, Texas native Gatemouth Brown to a management deal in 1947. But after Brown’s first two singles on Aladdin Records in Los Angeles went nowhere, as the label focused on Houston boogie woogie piano king Amos Milburn, Robey told Johnson they should start their own label. “How do you start a record label?” Johnson asked Robey, to which he reportedly shot back, “Hell if I know! That’s for you to find out.”

Johnson called the Library of Congress, which didn’t put out records, but referred Johnson to companies who did. She called them all, and asked questions. They were extremely helpful, as Johnson got an education in contracts, copyrights, royalties, publishing and even learned what Peacock would need to press their own records.

“Maybe people were just more inclined to help a woman,” Johnson once offered. It turned out that being one of the few women in the music business could be an asset as well as a liability, and for every lout who asked to “speak to your boss,” there was someone who’d go out of their way to help that nice lady from Houston who thought she was going to start a record label.

“Half the time we didn’t know what we were doing,” Johnson told writer Galen Gart. “We just tried to do right and take care of business. The rest took care of itself.”

The first African American record mogul, Robey distrusted other businesses and kept as much as possible in-house, including pressing the records, so Johnson had to learn it all. Robey required all his studio drummers to follow the beat of a red light in the studio that simulated the rhythm of a human heart. That’s what Evelyn Johnson did on the business side. She was “Robey’s discreet and proficient enabler,” according to Roger Wood’s 2003 book Down In Houston: Bayou City Blues (UT Press). But think of all the music that might not have been made if not for Johnson’s gift for facilitation.

No Comment