By Thomas D. Mooney

Terry Allen was 36-years-old when he released his second album, the double-platter, all-encompassing monolith Lubbock (on Everything). Released in 1979, it spoke about Lubbock and the Panhandle in ways unheard before — at least when it came to recorded music.

The arrival of Allen’s Lubbock (on Everything) switched a light on for a Lubbock scene that was very much in its infancy. It was as much an anthem for the outliers, outcasts, and ostracized as it was an approval and confirmation that there were others who thought within the same wavelength. Lubbock’s impact on Allen revealed Lubbock’s — or your hometown’s — impact on yourself.

37 years later, those principles still ring true. Lubbock (on Everything)’s impact on songwriters, artists, musicians, and avid music listeners is still as powerful as it was in the summer of ’79. The pulse of the 21-tracks feel strong and steady, and the album’s organic, robust sound — it’s as if Allen and company just finished recording it at Caldwell Studios last night. It’s as durable and enduring as it is relevant. All of which is why Texas Tech University’s “Lubbock Lights: Celebrating the Musical Heritage of the South Plains” program saw fit to pay special tribute to the album and its creator last Thursday night (Feb. 18, 2016) at the university’s Allen Theatre. Allen and his writer/actress wife, Jo Harvey (who now live in Santa Fe, New Mexico), were of course in attendance, along with a host of collaborators and friends (including Lloyd Maines, Robert Earl Keen, and Delbert McClinton) — and a whole lotta very lucky Texas music fans, who were treated to the first ever (and possibly last) live performance of Lubbock (on Everything) in its entirety.

For those who couldn’t be there in person, here’s a full recap — one album side at a time.

Side A

“Tomorrow, you may get a different answer, but tonight, this is the Terry and Jo Harvey Allen Theatre,” declares Texas Tech University Interim President John Opperman, and the sold-out crowd erupts in a mix of laughter, hoots, hollers, and applause. He’s followed soon after by Chancellor Robert Duncan, who announces with great pride that the Texas Tech University Library and Special Collections will be the future home of the Allen collection.

“These archives are more than just papers, images, and sounds that record decades of work,” Duncan says. “With this collection also comes Terry and Jo Harvey Allen and their commitment to engaging with Texas Tech, the Lubbock community, and future collaborators near and far.”

After those opening announcements, Jo Harvey takes the stage. She will be the narrator throughout the two-hour performance, providing the sort of colorful, insightful commentary only she can deliver. “You know, it’s kind of weird,” she says as the band gets ready at the side of the stage. “I don’t think it’s an accident that you called this ‘Lubbock Lights.’ It was two years after those sightings that Terry landed like a force. We just started bopping like crazy — and we haven’t stopped for over 60 years. I wake up every morning and look over at him and wonder what planet he’s really from.”

It’s a theme she’ll revisit time and again throughout the evening, marveling at how her husband’s imagination, thought process, and genius must mean he’s really from somewhere else than Earth. “[He] says he was born in Kansas,” she says skeptically, noting that she’s never actually seen his birth certificate. Hell, Superman was “from” Kansas, too. Maybe Terry Allen is from another planet. But Jo Harvey’s not exactly of this world, either.

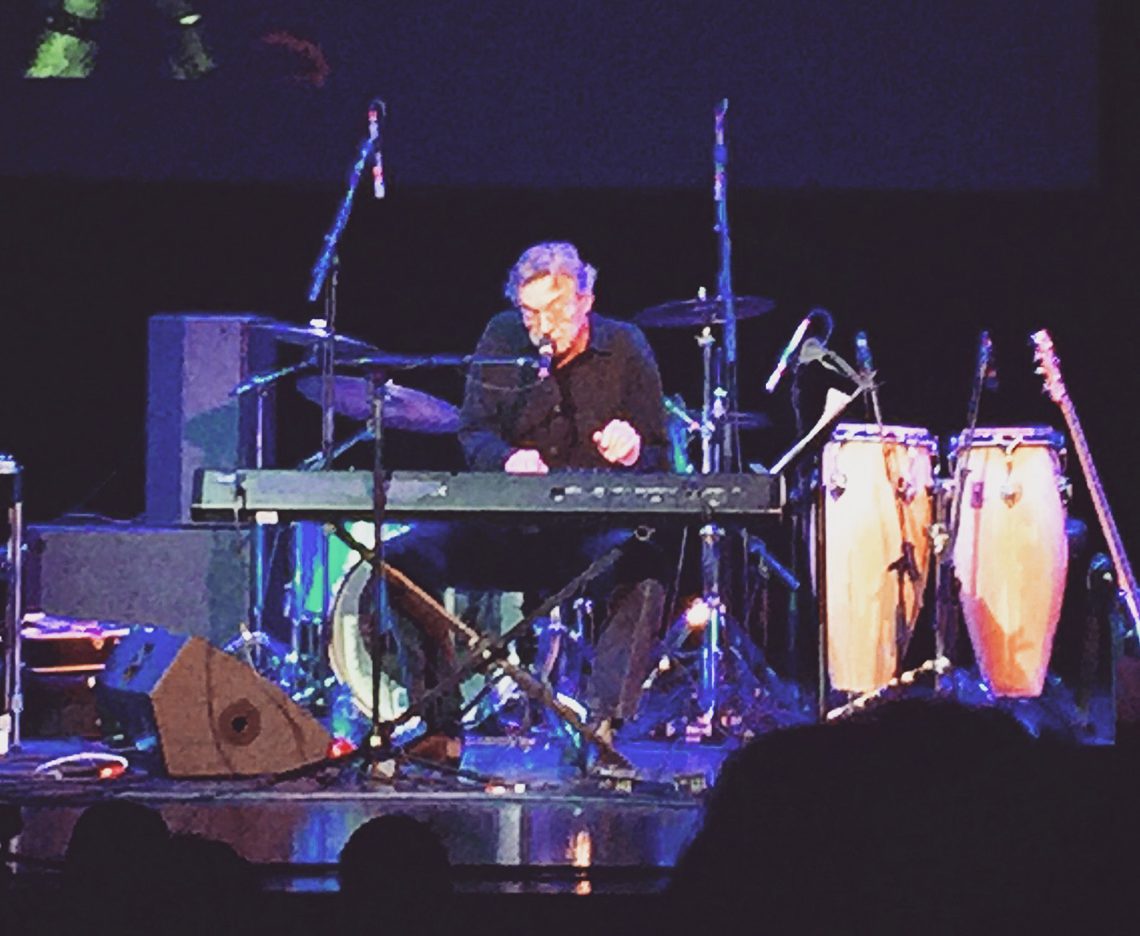

“I’ve been his main inspiration — for better or worse,” she continues playfully. “He wouldn’t even be a songwriter if it wasn’t for me. You listen to ‘Amarillo Highway,’ you be the judge.” With that, she introduces Terry, his Panhandle Mystery Band (Lloyd, Kenny, and Donnie Maines, Richard Bowden, and Curtis McBride) and “their two half-Martian sons,” Bukka and Bale Allen (both accomplished musicians and artists themselves). A grinning Terry hugs Jo Harvey as they pass one another and waves at the crowd on his way to his keyboard centered on the stage.

“I’d like to ask one of our special guests out, Mr. Robert Earl Keen,” says Allen. “He came in costume tonight.” Out walks Keen, dressed in a black blazer fitted with silver rhinestones on each shoulder, and together they launch into perhaps Allen’s most popular song, the rowdy, jangling album-opener, “Amarillo Highway.” It’s a song Keen has played for untold thousands of his own rowdy fans over the years, ever since recording it on his breakthrough 1993 album, A Bigger Piece of Sky.

“I’ve always felt a connection to Terry,” Keen enthuses post-performance. “The first time I ever heard that record [Lubbock], it sounded so familiar to me. It was like you lived it in a past life or you dreamed it sometime.”

After “Amarillo Highway” and “High Plains Jamboree,” Allen introduces the regional football tragedy “The Great Joe Bob” — as “a religious song … at least it’s religion around here.”

Many of the songs on the first half of Lubbock (on Everything) deal with escapism. It’s “making speed up ol’ 87” in “Amarillo Highway.” It’s not giving a damn about the consequences of leaving Lubbock — at least momentarily — and searching for “that good ol’ American Dream” in “Wolfman of Del Rio.” You see it in the “Girl Who Danced Oklahoma” as she makes her way out west to California after never being content with “living close to the bone.” But it’s more than just physically looking to get out of the flatlands of the Panhandle though. “High Plains Jamboree,” “The Great Joe Bob,” and “Lubbock Woman” dive past that layer of leaving. They’re about leaving who you are, even when you’re marooned in the Hub City surrounded by a sea of cotton rows. Joe Bob, the cheating family man of “High Plains Jamboree,” and the Lubbock woman — they’re all trying to convince themselves they’re actually someone else. They’re searching for someone to make “jukebox memories.”

“One of the things I always loved about Terry is that he’s totally unafraid to use everyday language,” observes Keen. “There’s no pretense in anything he does. If he had said, ‘breathing hard with a dark-eyed boy who she barely even knew,’ it wouldn’t have sounded as good as ‘she barely even knowed.’”

SIDE B

“Delbert, I always think of that great song of yours,” Jo Harvey tells special guest (and fellow Lubbock native) Delbert McClinton, then quotes a line from his “Two More Bottles of Wine] “‘They headed West with a common desire / The fever they had might have set the whole world on fire.’

“And we burned it up!” she says. “We went back and forth from L.A. to Lubbock to everywhere.”

Terry grabs a sheet of paper, glances over at fiddler Richard Bowden on his far left, and begins playing “Truckload of Art” — beginning with the spoken-word intro about the East Coast artists and painters who began feeling superior to their ego-counterparts out on the West Coast. It’s on this song that Allen has his first (and really only) flub of the night, missing the chorus the third time around. But he laughs it off with a shrug, and the audience does, too.

“See, right now, I’m in that art mode,” Allen explains. “Soon as you do that, everything else starts falling apart.”

Hardly. The band launches right into “The Collector (and the Art Mob),” inarguably one of the best moments of the night. For a band consisting of individuals all past the age of 60 (excluding Bukka and Bale Allen, both in their 40s), they rock harder and louder than any modern-day Texas bands. Bowden’s fiddle playing is sharp, edgy, and a force to be reckoned with; he towers over the others in the room whenever he’s called upon. In a peculiar way, it’s here where you can see Allen’s influence on songwriters such as Ryan Bingham the most. Part of that is Bowden’s presence in Bingham’s current band, but the overall weight and tone of “Truckload of Art” and “The Collector (and the Art Mob)” undoubtedly hits the same stride as any of Bingham’s rougher anthems.

As Jo Harvey mentions before the start of Side B, Lubbock’s second set of songs primarily deal with Terry’s first years in California — after his escape from the Panhandle — and the realities of a struggling artist. Specifically, “Truckload of Art” bends reality with a story so bizarre and outlandish that it just must be true; Allen describes the truck so vividly, he must have seen that “Art Ark” rolling down the highway himself. It sets the table for his L.A. art adventures with a tale about the “Art Mob” that’s every bit as cautionary as “The Great Joe Bob.” The snobbery and hubris within the art worlds of egotistical East Coasters and snotty surfer upstarts is a small one. It’s exclusive. That’s why he went blue-collar and joined the assembly line of the factory in “Oui (A French Song)” and “Rendevouz USA.” In those songs, he shows the contrast of being a “beer drinking regular guy” with what’s supposed to esthetically sound elite and elegant with all its French “ouis,” “sa la veys,” and “sa la guerres.”

SIDE C

“When we recorded Lubbock (on Everything), Don had a hat similar to the one he’s wearing now, but he also had these collars on these shirts that would put your eye out if you weren’t careful,” recalls Terry as Don Caldwell joins the Panhandle Mystery Band with his saxophone in hand. “You’d be in the studio and these wings would be flapping.”

A standout moment of the night happens during “The Beautiful Waitress” and “High Horse Momma.” The harmonies of Terry, Bowden, Lloyd, and Kenny Maines are as clean and pure as they were in 1979. Terry again picks up a sheet near the end of “The Beautiful Waitress” to recite the touching, yet comical conversation between him and the waitress about drawing sausages … err, horses. Without skipping a beat, they go directly into the often-forgotten rocker “High Horse Momma,” a track which was sadly cut from Lubbock (on Everything) for space reasons when the album was released on CD.

Even though “Blue Asian Reds (for Roadrunner)” is about the Vietnam War — something that could be perceived as dated, its subject is as significant for this latest generation as it’s been for any. You can hear in Terry’s voice that it’s still as close and heavy as it was when he wrote it. Lloyd Maines’ pedal steel playing throughout has been spectacular, but on “Blue Asian Reds,” he captures the lonesomeness and heartbreak with intimate wails and moans.

Maines is pulling double duty tonight, as he’s also playing bandleader and musical conductor — a role that becomes especially apparent on the more up-tempo songs, like “New Delhi Freight Train.” As the song builds steam, Maines shouts cues over the din to his brother Kenny and Bowden and nods to McClinton, who rejoins the band on harmonica (a part played on the record by Joe Ely.)

SIDE D

“It all comes full circle,” says Jo Harvey. She talks about how, back when they were all in high school, she and Terry and their friends used to drive out past 82nd St — which was all dirt roads at the time — and park their cars in a circle out in the cotton fields. They’d turn on their headlights, tune their radios to XERF out of Del Rio, and “howl with the Wolfman and dance in the headlights.”

Lubbock guitarist Casey Maines (Hogg Maulies and 108 East Broadway), Donnie’s son, joins Keen and McClinton and company onstage for the iconic “FFA” and “Flatland Farmer.” He lays down his rendition of the aggressive picking masterpiece that Jesse “Guitar” Taylor created all those years ago on the coupled songs. Again, they show they’re still equipped with as much grit and West Texas dust as ever.

Next, Allen goes into the soft, self-cognizant “My Amigo.” It’s really the first time on Lubbock (on Everything) that Terry accepts the “full circle.” As he explained in an interview earlier in the week, “I think it was just a realization of where you come from is important. No matter where you come from, there’s a richness that can be tapped into. Part of it, it’s made you into the kind of person you are … I think that’s what I was really coming to terms with.”

Fellow Lubbock native McClinton can clearly relate. “It’s incredibly poignant,” McClinton says his friend’s landmark album. “There’s something magical about it. Every time I listen, it’s like the first time. He pretty much nails what it’s like to grow up in a flat place. The vernacular of the time, it’s right on the money.”

Caldwell returns with his sax for the nostalgic “The Pink and Black Song.” The mood is playful, but also bittersweet: we all know the “record,” and with it this once-in-a-lifetime performance, is coming to a close.

“This next song … well, I’ll tell you in a minute,” says Allen before going into the intimate, loving, and faithful “The Thirty Years Waltz (For Jo Harvey).” Again, he picks up a side sheet and reads the introduction about first meeting Jo Harvey at a dance in 1956. It’s the crown achievement for Allen as he reveals the pure adoration for his muse. In some respects, you feel as though you shouldn’t be privy to the song. In others, you feel inadequate in comparison. But most of all, you feel satisfied that there’s something as genuine as the Allens’ flame.

After “The Thirty Years Waltz,” everyone leaves the stage but Terry. The last song on the album is called “I Just Left Myself,” and he closes the circle all by his lonesome.

But not for long. Soon, he’s joined by everyone once again for a rousing rip through another one of Allen’s greatest hits, “Gimme a Ride to Heaven Boy.” Although they’ve been letting loose and having fun all night, the encore certainly has a feeling of relief and exhale — not in a “finally, we’re done here” kind of way, but more so in satisfaction with the night’s performance. They finish up with the quitter, but no less powerful, traditional “Give Me the Flowers,” and Terry looks to the crowd with a smile of pure gratitude. He rises from behind his keyboard, and takes a bow with the rest of his friends, family and loved ones in front of a standing ovation.

“I hope you get your flowers, Lubbock, Texas,” he tells the crowd. “Thank you very much.”

Terry Allen and the Panhandle Mystery Band (and a few very special guests) performing “Lubbock (on Everything)” at Texas Tech University’s Allen Theatre. (Photo by Thomas Mooney)

SETLIST

- John Opperman, Tech Tech University Interim President Welcome

- Robert Duncan, Texas Tech University Chancellor Special Remarks

- Jo Harvey Allen Introduction

- “Amarillo Highway (fr Dave Hickey)” w/ Robert Earl Keen

- “High Plains Jamboree” w/ Robert Earl Keen

- “The Great Joe Bob (A Regional Tragedy)”

- “The Wolfman of Del Rio”

- “Lubbock Woman” w/ Delbert McClinton, Gwen Decker, Suzanne Henley

- Jo Harvey Allen Commentary

- “The Girl Who Danced Oklahoma”

- “Truckload of Art”

- “The Collector (and the Art Mob)”

- “Oui (A French Song)”

- “Rendezvous USA” w/ Robert Earl Keen (acoustic guitar)

- Jo Harvey Allen Commentary

- “Cocktails for Three” w/ Don Caldwell (saxophone)

- “The Beautiful Waitress”

- “High Horse Momma” w/ Don Caldwell (saxophone)

- “Blue Asian Reds (for Roadrunner)”

- “New Delhi Freight Train” w/ Delbert McClinton (harmonica), Robert Earl Keen, Gwen Decker, Suzanne Henley, Don Caldwell (saxophone)

- Jo Harvey Allen Commentary

- “FFA”

- “Flatland Farmer” w/ Casey Maines (lead guitar), Robert Earl Keen, Delbert McClinton

- “My Amigo”

- “The Pink and Black Song” w/ Don Caldwell (saxophone), Gwen Decker, Suzanne Henley

- “The Thirty Years Waltz (for Jo Harvey)”

- “I Just Left Myself” (solo)

- Encore: “Gimme a Ride to Heaven Boy” w/ Everyone

- Encore: “Give Me the Flowers” w/ Everyone

[…] years ago, Terry Allen released Lubbock (on Everything). It’s widely considered the greatest, most complete piece of work in Panhandle Music history. […]