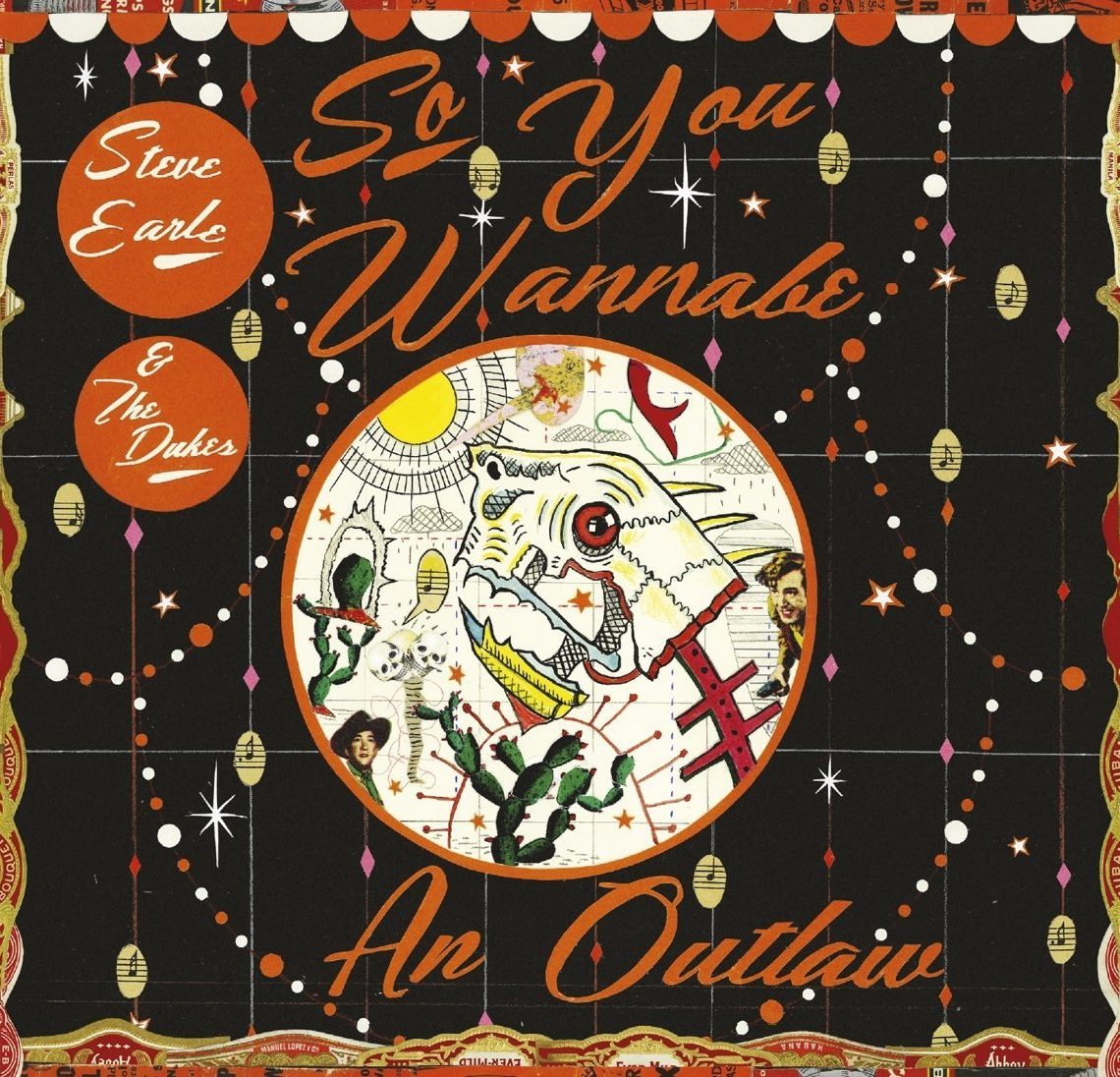

STEVE EARLE & THE DUKES

So You Wanna Be an Outlaw

Warner Bros.

Some of the great outlaws of country music are actually a pretty soft-spoken bunch: the Willie Nelsons, Guy Clarks, and Ray Wylie Hubbards of the world, kicking up considerable dust onstage and on record while keeping it pretty low-key and good-humored offstage, at least after a certain maturity kicked in. But Steve Earle is, to quote one of his own songs, “the other kind.” The unrepentant hardcore troubadour has been an outspoken firebrand from day one, and even though he kicked the addictions and resultant legal troubles that brought his career to a temporary standstill (and nearly killed him) a couple decades ago, sobriety hasn’t exactly quieted him down much. If anything, with maturity and clean living he’s only doubled down on the voluble swagger, personal tumult, and in-your-face opinions that have long seemed inseparable from his music. For evidence, just witness some of the press he’s done recently for So You Wanna Be an Outlaw, taking a number of digs at both the music business and a few specific artists both on and off the Americana playing field. Through most of the last decade, he also distinguished himself — for better or worse, depending on whether you personally lean left or right — as one of the most unapologetically politically-charged songwriters of his generation.

One thing Earle’s never been, though, is predictable. After scaling back a bit on the outright protest anthems from, say, 2008-2016, you might expect him to fire them back up right about now. But instead of another The Revolution Starts … Now, we’ve got an album that’s actually looking back a little. So You Wanna Be an Outlaw is at least sort of a genre excursion, not unlike his bluegrass jaunt with 1998’s The Mountain or 2015 blues record Terraplane. But seeing as how Earle is more of a direct descendant of Willie and Waylon and the boys (and even more directly of Guy and Townes and the less-famous boys) than he is of Bill Monroe or Son House, the musical appropriation isn’t nearly as obvious. At least once you get past the opening title track, which is pretty damn specific: there’s the stomping beat, the rumbling Tele, and the “Waymore’s Blues”-ish melody even before Willie Nelson himself chimes in for the duet portion. Starting off like this, one would assume this might be a whole album of naked attempts to fill Waylon Jennings’ boots, or at least try them on.

But as the record goes on, Earle and his band hit diverse enough notes to shake off any retro-project constraints. The raggedly tender “News From Colorado” and “The Girl on the Mountain” could’ve fit into pretty much any Earle album. The fatalistic stomp of “Fixin’ to Die” sounds more like the full-tilt rock of the Drive-By Truckers than anything plucked from the ‘70s, but other than that this feels like more of a straight-up country album than most of Earle’s efforts. Not least of the reasons why is the almost ever-present fiddle, mostly courtesy of splendid Dukes bandmate Eleanor Whitmore but also memorably pinch-hit by Reckless Kelly’s Cody Braun on the swinging Johnny Bush duet “Walkin’ in L.A.” Bush’s stately croon and Earle’s graveled drawl are unexpectedly simpatico; when Earle acolyte Miranda Lambert joins in on the jangling “This is How It Ends” (which she also co-wrote), it’s a more seamless but no less satisfying fit.

Folks who treat themselves to the vinyl or deluxe versions get a hearty dessert of Earle covering vintage Willie, Waylon, and Billy Joe Shaver, all of which fit him like a glove (or the aforementioned Waylon boots). But for the rest, the record wraps up on “Goodbye Michelangelo,” a tribute to Earle’s recently departed friend and mentor Guy Clark that lovingly borrows his signature sparse, darkly intricate finger-picking style. “This ain’t forever, it’s just goodbye till it comes my time/I won’t have to travel blind/You taught me everything I know …” Earle drawls through a stiff upper lip. Sure, he might have more attitude than everyone’s inclined to handle, but his gratitude to what’s come before is evident, becoming, and a great jumping-off point for a solid album. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment