By Greg Ellis

(May/June 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 3)

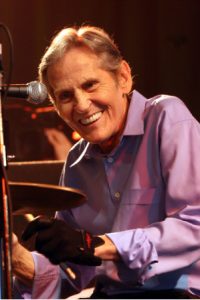

As I write this, Levon Helm has been gone for two weeks, and by the time you read it that period will be significantly longer. You will probably have read dozens of tributes to him by this point. It doesn’t matter. His greatness can never be in doubt and his significance cannot be minimized. In his manner and his music, Helm represented the best America has to offer. He WAS “Americana.” Fitzgerald’s famous statement that there are no second acts in American lives was emphatically disproved by Helm’s 21st century renaissance.

Helm’s voice was an American treasure, somehow condensing every aspect of our history and lives into a sonorous gift from God that allowed all our hopes and our tragedies to be expressed, as if it were the voice inside each of our own heads. However, it wasn’t his voice that initially set Helm on the road to greatness. It was his drumming, simultaneously loose limbed and incredibly tight, that first attracted the attention of fellow Arkansan Ronnie Hawkins. Hawkins tapped him for a Canadian tour and it was there he met the other members of Hawkins’ band and his journey to legend began.

Hawkins’ band was called the Hawks and consisted of four young Canadians: Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson and Garth Hudson. They toured all over Canada playing rough dives that made an Arkansas roadhouse look like a House of Blues. It was in one of these dives that Mary Martin saw them and subsequently suggested them to her boss, Albert Grossman, when his client Bob Dylan was looking for a back-up band.

As hard as it is to imagine now, Dylan’s new direction and Hawks-powered electric rock sound provoked widespread outrage. The stress of the craziness that was life with Dylan in those days, combined with the hostility of the crowds, led Helm to quit the Hawks for a time. Over a year passed before he rejoined the Canadians, who were still making music with Dylan while the songwriter was recovering in seclusion from a motorcycle accident. They were doing it in the basement of a big pink house in Woodstock, N.Y.

The music Dylan and the Hawks created in that basement is justifiably legendary, a bucolic yet surreal take on “the old, weird America.” Manuel was also a gifted drummer, which freed Helm to show off his prowess on the mandolin, which he had learned from his father. During this period Helm and Robertson would have long conversations about life in the rural South, culminating in them writing songs together (Helm’s version of the story) or Robertson being “inspired by Levon” (Robertson’s version). Those songs would wind up on the first two records the group made after leaving Dylan. They were no longer the Hawks. Now they called themselves The Band, because that was what everyone else called them.

The impact those first two Band albums had on the underground and the music world cannot be overstated. In a time when chaos and experimentation reigned supreme, the simplicity of the songs and the economy of the playing was a revelation to an audience that was just beginning to understand that they didn’t want to be insane all the time. But the beauty of those records is that understanding that context is completely unnecessary to the enjoyment of the songs. Over 40 years on they remain some of the finest music this country has ever produced. Songs like “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” sound like they have been around forever, and they most certainly will be. Both have been covered by many of the world’s best singers, but no other voice ever mainlined them directly into your soul the way Helm’s did.

The next five years brought a series of diminishing artistic returns as egos and chemicals took their toll. Finally, in 1976 Robertson announced that The Band was ending. According to Helm, he did it without consulting the rest of them. A huge farewell was planned and executed. Dubbed “The Last Waltz,” it took place on Thanksgiving 1976 at San Francisco’s Winterland and was masterfully filmed by Martin Scorcese and featured guests like Muddy Waters, Bob Dylan and Neil Young. The subsequent film is almost universally regarded as the finest concert film ever made, and despite all the guest stars and Scorcese’s focus on his friend Robertson, Helm is clearly the star. The version of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” from that film has been shared millions of times since Helm’s passing and rightly so. It is one of the most compelling musical performances ever captured on film.

The next quarter century was a rough one for Helm musically. His first post-Band project was dubbed the RCO Allstars and also featured Dr. John and Paul Butterfield, who were dealing with the same sort of destructive impulses that crippled The Band. A bland and mundane solo album followed which went nowhere. Then Hollywood called. Helm’s unlikely career as a character actor began with his role as Loretta Lynn’s father in Coal Miner’s Daughter and continued with a prominent role in The Right Stuff. Overall, he appeared in 15 films in the next decade and a half.

In the early ’80s, The Band reunited without Robertson and toured frequently. The same issues continued to plauge the members though and sadly no recordings were made. The crowds got smaller and smaller. This period came to a sad end in 1986 with the suicide of Manuel.

In 1993 Helm published an autobiography called This Wheel’s On Fire in which his anger and bitterness towards Robertson was very publicly aired. Angry that the intensely collaborative music of The Band had enriched Robertson far more than the rest due to a decision between Robertson and Grossman to give Robertson sole songwriting credit for much of it, he accused Robertson of everything from “going Hollywood” to causing Manuel’s death. It was a surprisingly angry tome from someone as genial and gracious as Helm.

The same year that Helm’s book was published also saw the release of the first of three mostly forgettable semi-reunion Band albums featuring Helm, Danko and Hudson. They’re all mostly forgettable, although the first one, Jericho, did contain a striking version of Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City” which Helm unsurprisingly made his own. But I saw this version of The Band around this time and it was one of the most disappointing shows I have ever seen. Danko was simply in no shape to tour, scratching himself and nearly nodding off throughout the entire, truncated 45-minute set. Helm left the stage visibly upset. There was no encore.

In the late ’90s came the sad news that Helm had been diagnosed with throat cancer. Rather than have his voice box removed, he opted for a series of radiation treatments that shrank the tumor to the point where it could safely be removed. However, it led to Helm’s once magnificent voice being reduced to a raspy whisper. This, combined with Robertson’s aversion to touring and Danko’s sad but inevitable death in 1999, led everyone to believe that the music of The Band would never be heard on a concert stage again. Helm would prove all of us (including Fitzgerald) wrong.

The Midnight Rambles began in 2002. A weekly Saturday night show in Helm’s Woodstock barn, the Rambles were originally a way for him to raise money for his medical bills and initially featured Helm’s drumming behind a different high profile guest each week. They proved immensely popular, selling out every weekend. By 2004 Helm began to tentatively sing a song or two, and over the next three years, as his voice got stronger and stronger, talk grew about a new record. Released in the fall of 2007, Dirt Farmer was a triumph. A mostly acoustic record, one could not help but think of the glory days of The Band, especially on Helm’s version of Steve Earle’s “The Mountain.” Dirt Farmer won the Grammy that year for Best Traditional Folk Album.

In 2008 Levon took the Ramble on the road, playing among other high profile gigs, the Bonnaroo festival in Tennesee. He also played a show at the historic Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. I was one of the lucky ones in attendance and it was, quite simply, one of the best shows I have ever seen. There were a terrific number of guests, all of whom were great but none of whom could steal the spotlight from Helm. The majesty of the music combined with Helm’s glowing spirit in that most holy enclave of American music made for one of the best nights of my life. The following year saw the release of Electric Dirt, another triumph. “Growing Trade,” a gripping tale of a family farmer forced into weed farming to feed his family, was as complex and deeply American as any Band classic and added fuel to the argument that The Band’s songwriting was far more collaborative than Robertson would admit. Electric Dirt took home the Grammy in the newly created Americana category.

Helm continued to have weekly Rambles in the barn (the 200th was celebrated last year) and taking the show on the road. In 2011, Ramble at the Ryman, a CD and DVD of the show I saw in 2008, was released and, not surprisingly, took home this year’s Americana Grammy.

Helm continued to perform until March of of this year. A series of cancellations was followed by the sad announcement in mid April from his family that Helm was in the final stages of cancer. Robertson flew to New York and sat as his bedside. Afterwards he released a statement: “I sat with Levon for a good while, and thought of the incredible and beautiful times we had together. Levon is one of the most extraordinary talented people I’ve ever known and very much like an older brother to me. I am so grateful I got to see him one last time and will miss him and love him forever.”

On April 19 came word that Helm was gone, his exit handled with the same simple dignity that had characterized his life. On April 27 he was buried in Woodstock next to his old friend Danko. I would like to believe that they will harmonize for all eternity.

Thank you, Levon Helm. You made the world better while you were here.

No Comment