By Richard Skanse

Sunny Sweeney does more before 9 a.m. than most late-rising lazy music writers do all day. Granted, so does just about everybody, so that’s not really saying a lot; but considering we’re talking about a touring musician here — meaning Sweeney’s one of those “night people” whose job it is to take the day’s people’s money, per Ray Wylie Hubbard — props are in order. Because even although it’s actually 10 a.m. on her end of the line out on the East Coast, odds are she still would have already been up for hours on one of her rare days off back home in Texas. Chastise her sleepily about her apparent disregard for respectable “rock star hours,” and she readily admits that “I don’t even know what those are anymore.”

Truth is, she never really did.

“Randy and I used to talk about that, like right after we got out of college, because both of us were always up doing stuff really early, and as he said, ‘that’s when you get stuff done,’” she recalls, referring to her old Texas State University pal (and fellow public relations major) Randy Rogers. Rogers got a few years head-start ahead of her on his own music career, but Sweeney was quick to learn first hand the merits of waking up with her namesake. “Back in the day, I was booking myself and managing myself and all that, and you have to get up early in order to be able to do anything. Because the club owners aren’t going to be there later; especially the older guys, they’re up at the crack of dawn, so they’re at the bar wanting to take care of business.

“I remember I would call places midday, and whoever answered would be like, ‘The boss is here from like 9 to 10,’” she continues. “And I was like, oh my God, 9 to 10? So you’re saying I’ve got to get up early to be in the music business? I got into this so I wouldn’t have to get get up early. But It ended up working out for me. I actually like getting up early now.”

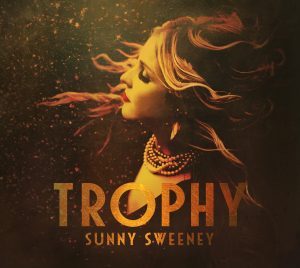

Not that Sweeney’s ever been a slacker. Going all the way back to before she self-released her 2006 debut, Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame, she’s busted ass at every level from scrappy DIY independent to Big Machine-powered Nashville star and back again. Along the way, she’s cracked both the Billboard Top 10 album and singles charts (with 2011’s Concrete and “From a Table Away,” respectively), played to sold-out arenas opening for the biggest names in modern country, and performed on the Grand Ole Opry more times than … well, not more than she can remember, but enough times to pretty much blow her mind every time she tallies them up. In fact, March 7, five days after our phone interview, marked her 48th appearance on that hallowed stage — not a bad way to kick off the release week for her fourth album, Trophy (out today, March 10, via Thirty Tigers).

This is Sweeney’s second album since returning to her indie roots after an eventful five-year spin in the major label system, and even more so than 2014’s fearlessly forthcoming and critically acclaimed Provoked, it’s a start-to-finish artistic and personal triumph. Trophy is 36 filler-free minutes of smart, funny, and at times heartbreakingly perfect country music showcasing Sweeney’s Texas-sized wallop of a voice — not just as a powerfully assertive singer cut from the same sassy mold as Natalie Maines, but as a songwriter capable of holding her own trading lines and melodies alongside the formidable likes of Lori McKenna. Not too shabby for a gal who just 14 years ago started this whole country music career thing pretty much on a lark, much to the bemusement (and no small amount of concern) of the handful of friends, family, and co-workers she invited to her first-ever gig at a South Austin dive bar. But no matter how far she’s come in making her dream manifest since then, it’s clear she hasn’t taken a minute of any of it for granted. Take it from someone who not only remembers that first show of hers, but who’s talked to her enough times both on and off the record since to know that, even though she may be the consummate, up-at-the-crack-of-dawn professional, Sweeney’s go-to response to just about any measure of success or new opportunity to come her way in the business is almost always a genuinely bewildered “Dude …!”

This is Sweeney’s second album since returning to her indie roots after an eventful five-year spin in the major label system, and even more so than 2014’s fearlessly forthcoming and critically acclaimed Provoked, it’s a start-to-finish artistic and personal triumph. Trophy is 36 filler-free minutes of smart, funny, and at times heartbreakingly perfect country music showcasing Sweeney’s Texas-sized wallop of a voice — not just as a powerfully assertive singer cut from the same sassy mold as Natalie Maines, but as a songwriter capable of holding her own trading lines and melodies alongside the formidable likes of Lori McKenna. Not too shabby for a gal who just 14 years ago started this whole country music career thing pretty much on a lark, much to the bemusement (and no small amount of concern) of the handful of friends, family, and co-workers she invited to her first-ever gig at a South Austin dive bar. But no matter how far she’s come in making her dream manifest since then, it’s clear she hasn’t taken a minute of any of it for granted. Take it from someone who not only remembers that first show of hers, but who’s talked to her enough times both on and off the record since to know that, even though she may be the consummate, up-at-the-crack-of-dawn professional, Sweeney’s go-to response to just about any measure of success or new opportunity to come her way in the business is almost always a genuinely bewildered “Dude …!”

Good morning, Sunny.

Wow, dude … you are efficient! Sorry, did I wake you up, making you call this early?

Well of course. But that’s OK. You’re on the road, so I probably got more sleep than you did, anyway. Where am I catching you this morning?

We stayed at my cousin’s last night in Virginia, basically right outside of Washington, D.C. This whole run is like a bunch of driving. We did I think 15 hours one day, and about 12 hours yesterday. Then I went to bed at like 2 a.m. last night and got up at 7:30. I know … it’s ridiculous! But I’m hanging out at my cousins’ today, visiting, and tonight we’re playing in Frederick, Maryland. After that we’re doing the Hill Country Barbecues in New York and D.C., then a place in Cincinnati and the Basement East in Nashville. Oh, and I’m doing the Opry again next week, too.

How many times will that be for you?

This will be the 48th. I know! And actually, this is my 10-year anniversary, today, of doing the Opry for the first time, because it’s Texas Independence Day, and I first did it in 2007. Which is funny because … well, this is why I’m in music and not math. Little Jimmie Dickens’ steel player used to record the Opry, and he gave me a copy of my first performance like maybe a year after I did it. And it’s terrible, because I just cried and and screamed and danced around onstage, I was so stupid … but, anyway, I was looking back at it the other day and it said “March 2, 2007,” and I went, “Oh my God, that’s been like six years!” [Laughs] And then I was like, “Or not … it could be 10, because it’s 2017.” You can see why I have a CPA and do not need to do math, ever.

As excited as you were that first time, has it gotten to the point yet where you’re like, “Oh, we’re doing the Opry again? Sigh …”

Oh hell no! Hell no. No. I still get so nervous. And I even get nervous asking if I can do it. Because I keep thinking they’re going to be like …

“We’ve already had you 47 times, Sunny …”

I know! I keep thinking they’re going to be like, “You know what? We’ve decided that we think you suck, so you’re never coming back here.” [Laughs]

This year is also the 10-year anniversary of Heartbreakers Hall of Fame, isn’t it?

Actually, that originally came out in 2006.

Oh right — 2007 was when Big Machine picked you and re-released it. But close enough. My favorite song on that record was one of the ones you wrote, “Ten Years Pass.” So looking back, does it really feel like it’s been that long to you?

No! Dude, it feels like … Well, somedays it feels like, oh my God, I’ve been here, doing this, I need something good to happen, something to change … But then I look back and I realize that so much has changed. Like somedays it feels like it’s been 50 years, and some days if feels like it’s been two. Like I could not believe that it’s been 10 years since I first did the Opry. I could not believe it. I don’t even know how that happened.

It’s amazing to think about how, on one hand, a decade is obviously a big chunk of someone’s life; but at the same time, it’s gotta blow your mind to realize how much your life has changed in that time. Not just in terms of going through “regular life” stuff like a divorce and getting married again, but the fact that not much longer than 10 or 12 years ago, you still had a desk job and had yet to even dream up any of this.

Well, it’s actually been a little longer than that, because … This is the other thing that freaked me out. Kelly, that’s my cousin, last night she was talking about the first gig that I had, which was at the Chaparral Lounge in 2003 — she did the math, not me, because she remembered it being when she was in town from North Carolina at the time. So I mean, 14 freaking years, and that to me is crazy. That is insanity. I cannot believe that I’ve been doing this for 14 years. Because it honestly feels like it’s only been five years. But my mom is like, “Go back and think about all the things you’ve gotten to do.” Like, I’ve been to Europe countless times — for music. I mean, somebody actually pays me to go to Europe and sing music. It’s so, so weird. I can’t even … I truly cannot even believe it sometimes.

Speaking of time flying, you’re now two albums past your Big Machine/Republic Nashville era. Obviously you’ve done this on your own before, with the original release of that first album, but how different was the making of these last two records from your experience making Concrete for a major label? Was it hard re-adjusting to being independent again, or was it more of a relief?

Well, it’s more legwork for sure. I’m doing more of the stuff that goes along with it. I mean I have a booking agent, and I have Thirty Tigers, which is distributing it, and that makes it easier, and I have a publicist that, you know, was actually my first publicist, so I’m excited to work with her again. But I’m making the decisions. And yeah, having a big label was certainly financially easier, because now I’m having to front everything; I have to figure out a way to make it work. But even though it’s harder and more legwork, it’s also so much more gratifying — way more gratifying — because I feel like I know that everything I’m doing is because I’m doing it.

But does it feel like starting over again in a way? Or did you feel like a lot of the doors that opened for you from being on a big label stayed open? Like with radio and press and such.

I didn’t really … I mean we did a little bit of radio with Provoked, but not a lot. But I do feel like I’ve made some really good friendships or made a good impression or something with a lot of the press people I’ve met over the years, because a lot of the same people show up with each record and they’re always extremely excited and supportive. Like there was a couple of years in a row where I didn’t do AmericanaFest in Nashville, and this one girl made a point to tell me, “I loved AmericanaFest this year, but you were missing … what you do was missing.” And I took that as the biggest compliment.

Just to be clear, she said “I loved AmericaFest, but you were missing,” not “because you were missing …”

[Laughs] Right! No. “I loved it but you were missing,” not “I loved it because you weren’t there!”

Kidding aside, though … the last time I interviewed you was back in 2011 when Concrete came out, so I had to do a little Wikipedia cramming last night to catch up on any news I might have missed regarding how Provoked did for you. I read that your “Bad Girl Phase” from that album was the first single by a female artist to top the (now defunct) Texas Music Chart in like, a decade. Knowing what a sausage party the Texas country scene can be, in a way that almost seems like more of an achievement than cracking the national Top 10 with “From a Table Away.” Did one of those mean more to you than the other?

Well, honestly, I don’t even know that that’s actually correct information (about the Texas Music Chart), because I’m pretty sure Stephanie Jones and Maren Morris both had No. 1’s on there, too. But the truth is I really don’t, didn’t, and won’t pay attention to charts, because it’s kind of like how I won’t even read press. I can’t remember who told me this, but I think it was Dale (Watson), he said, “If you’re going to believe good press, then you have to believe bad press, too.” So, you know, I’ll read stuff that my publicist will send me where she says, “This is cool, check it out.” But I’m not going to sit there and Google alert myself to see every time I’m mentioned, because I think it kind of devalues what you’re doing. And whether I get press or not, I’m going to continue doing what I’m doing, because I’m already so hip-deep in it … I mean, it’s not like I can go back to a desk job now — I have to make this work. So I’m not taking no as answer, I will not take no as an answer. And I never have.

I imagine seeing crowds responding to your music in a live setting is more gratifying than any chart position or review, anyway. In terms of playing live, where do you feel the most at ease at this stage of your career? Is it playing to a giant mainstream country crowd in an arena or amphitheater, or somewhere back home in Texas, like at the Saxon Pub or Gruene Hall? Does one feel more gratifying than the other?

No. I feel like they’re all different. But I love playing acoustic shows, like small acoustic shows, because it gives you a different outlook on kind of what you’re doing; you can try new songs, and if you screw up, it’s just you — it’s just you and a guitar, so you can’t blame anybody, so that makes you practice harder so that you don’t screw up. But I kind of get off on that, and I love being able to talk to my crowd. But at the same time, opening that (sold out) Cody Jinx show at Gruene show recently was probably one of the most badass crowds that I’ve ever played in front of; I loved that. I thought it was so fun, and you were there, so you know how they were actually into it. I think our music goes together, and I think we probably share some of the same crowd anyway, just because they like country. And then of course, there is nothing that feels the same as playing in an arena with big crazy lights and a huge stage, your heart’s beating a million miles a minute …

This is funny. My dad came to American Airlines Arena when I was playing with Miranda (Lambert). And you know, he’s the one who was at my high school talent show, kind of sinking down into his chair as I walked out onstage, because he was like, “Oh shit, what are we about to see?” And then he was like, “Oh my God, she’s good!” He just doesn’t want me to fail, because I’m his daughter and of course he wants success — I mean for me, not because he’s a stage father. So anyway, he came to see me at Miranda’s show and I saw him right after I got done and he went, “Oh my gosh, you did so good!” And I said “OK, Daddy, now I’ve got to go … when Miranda’s done with her main set, she wants me to come out back at the end and sing a Dixie Chicks song with her and Gwen Sebastian.” And my dad was like, “Wait, you have to sing with them? What if you mess up?”

[Laughs] I was like, “I’m not going to mess up.” And he goes, “But what if you do?” He was just so cute.

“Don’t shit the bed, baby!”

[Laughs] “Please don’t shit the bed!” Because that Miranda show was the biggest crowd that we’ve had, and it was pretty much like a hometown show for both of us. And I had so many high school friends that were there, and they were all like, “This is so cool, I can’t believe you’re doing what you always said you were going to do …” And to me, that’s another huge compliment and really gratifying, when people that I’ve known my whole life recognize that this really is something that I’ve always wanted to do. Not necessarily singing, but doing something onstage — acting or comedy or something. I always wanted to do something in the entertainment industry, and now I am, and trust me — it’s just as shocking to me as anyone.

Speaking of things you still can’t believe … I imagine writing four songs on this record with Lori McKenna has gotta be up there, no? Are you at the point yet where you can go into a writing session with someone like her thinking, “I’m cool, I’m bringing just as much worthwhile stuff to the table here as she is, we’re on equal footing …,” or are you like, “oh lord, Sunny, don’t …”

Shit the bed? [Laughs ] I always say I don’t want to shit the bed. I mean …

I don’t mean to keep putting those words in your mouth …

No, no, I always say that. But it’s really the equivalent of like … well, the other day I did a session with Bruce Robison down at his studio, and Redd Volkaert was the guitar player. Redd and I have been friends for a long time and we were talking and he was like, “Wow, it’s so cool that you’re doing so good!” But he’s still, you know, Redd Volkaert. So anyway, I’d say writing with someone like Lori is the equivalent of having to play in a band with Redd. Like it can be intimidating, but if you open your mind, you just learn. Anytime that I’ve ever played anything with Redd, I’ve learned from him, and every time I’ve ever written a song with Lori, mostly I just soak it in, because she’s so brilliant, it’s insane.

There’s actually a lot of people like that in my life that I feel like I’ve been fortunate to be around, that I can actually learn from. And I like learning; I didn’t like school, but I like learning things for my profession. And so like with Lori, you know, I have definitely brought in some ideas that we’ve written together, but she also … I don’t even know how to describe her. She’s just amazing. She’s open; and even though she’s only a couple years older than I am, she’s very maternal, so you want to open up and talk to her about things. Which is important, because if you want to write songs about personal stuff, you have to learn to be open about them and not be like, “Oh, I don’t really want to talk about this.”

You pretty much just described “Bottle By My Bed,” the song you wrote with Lori about the heartache of not being able to have kids. Is that situation …

Real? Oh yeah, it’s real. Jeff (Sweeney’s second husband) and I have been trying to have a kid for like five years, and it’s just not working. And it’s pissing me off, because it should be working. It’s so frustrating, because you go through all of the natural things, then you go through in-vitro and all that, and the doctors just can’t tell you why none of this stuff is working. Anyway, I wanted to write that song for a long time, and I thought Lori was the perfect person to write it with, because I mean, she’s got five kids, so she’s never been one to long for wanting a child, but at the same time, she more than anybody I know knows the love of a child. So we wrote it together and it ended up being exactly what I wanted the song to be. Before her, I tried writing it with a couple of other people, and they were kind of like, “Eh, I don’t now — sounds more like a drinking song.” And I’m like, “No, it’s definitely not a drinking song.”

Not that you’ve got anything against those. The album opens with a barstool lament called “Pass the Pain,” then goes right into “Better Bad Idea,” which begins with the line, “Let’s wash our dirty minds / with a bottle of white wine.” That’s a good one.

Thank you!

But even better than that is just the phrase and title, “Better Bad Idea” — I mean, that’s one of those where you’ve gotta be like, “How has this not been used before?” It’s like a $100 bill just laying on the ground in plain sight, and you wonder why nobody’s ever picked it up.

[Laughs] Well, we came up with that — we wrote that at 7:30 in the morning one morning; I wrote it with Buddy Owens, who’s one of my best friends, and Galen Griffin. We had started another song actually, and we were just kind of sitting on it — none of us could really function, because it was so early. And then we just kind of came up with that instead and ended up writing it pretty quick. And immediately after we wrote it I went, “Y’all, this is going on my next record.” I hadn’t even started making a new record yet — this was almost two years ago — but I was like, “That is badass. That is going on my record for sure.” I just think it’s so fun, and yeah, just like you said … I Googled it thinking, “Surely this is a song already.” Or something. But it isn’t; I couldn’t find anything on it.

Another one on that same wavelength, as far as “how has nobody thought of this before,” is the title track, “Trophy.” I love the fact that it could not be more bitchy. The melody even has that nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah kinda ring to it.

[Laughs] Well, that was the intention!

It’s a really brilliant take on that put-down notion of the “trophy wife” — where you turn the insult around on the bitter ex by saying, “Yeah, he’s got a trophy now, for putting up with you.”

Yeah. Actually, that line was Lori’s … I wanted to write a song with that title, and I told her kind of the story, about how one of Jeff’s exes … basically, I heard through the grapevine about how when he and I walked up to an event one day, his ex was like, “Oh, here comes Jeff and his trophy wife.” A friend of mine heard her and immediately told me, and I was like, “This woman clearly has no clue that I write songs, does she?” [Laughs]

To me that song actually bridges where I’ve been to where I’m going, I hope. Because like you said, it still has that, “nyah-nyah-nyah-nyah,” like smartassness, but when Lori came up with “He’s got a trophy now for putting up with you,” I died. I absolutely died. Like, “I’m dead, I’m super dead right now.” But when we wrote it, it was actually a little bit more … ragey, I guess. And I really wanted it to be more snarky. So when Dave Brainard and I started doing pre-production on it, I told him I wanted it to be more swingy than it was, so that the words would resonate more and be like, “heh-heh-hea-heh-heh.” So I’m glad that you said that, because to me it means so much more when you can really hear the words, and then you get to the hook and you’re like, “Annnnd there it is.” [Laughs]

There needs to be a fader level on the studio console, where you can be like, “Can you turn down the rage and bring up the sass on that a little?”

[Laughs] “Can you up the snark, please?”

On a completely different wavelength, is there anything you can tell me about the last song on the record, “Unsaid”?

I wrote that one with Caitlyn Smith in Nashville two Decembers ago; I think it was the day before my birthday. And I don’t really know who Caitlyn was thinking of, because we didn’t really discuss that when writing the song, but for me it was about a friend of mine who committed suicide like 10 years ago. And I was just pissed at him, furious, because there was so much I wanted to say and couldn’t say it, obviously. So that’s what it was about for me at the time. But if I go back and listen to it now, I feel like it could be about anything … your parents or your boyfriend or girlfriend, whatever.

Regardless, it’s a gut-wrenching, beautiful song. But that anger and frustration still comes through, which accounts for the word “shit” being dropped into the middle of it. When you do that, are you consciously thinking, “Well, this is never going to be a single anyways, so …”

Yeah, because I don’t really care anymore; I mean, it’s not like radio was going to play it anyway, so I feel like if it tells the story, then you need to say it.

Could you have gotten away with that with the “other guys” — i.e., back on Big Machine/Republic Nashville?

Oh no, no.

So there is more freedom now.

Oh God … I have all the freedom in the world. All I have to do is say there’s a bad word on there: “There’s the word ‘shit’ in there somewhere on this record. Find it!” Hide and seek! [Laughs]

There’s only two songs on the album that you didn’t have a hand in writing, but both of them are pretty much by family: “Pills,” by your friends Brennen Leigh and Noel McKay, and “I Feel Like Hank Williams Tonight,” by Chris Wall. You and Chris go way back, don’t you?

Oh yeah. I met him way before I started doing music, and we’ve maintained a really cool friendship. I’ve just always adored him. He acts like a mentor in some ways; when I started doing music, he’d be like, “Hey, come up and sing with me!” So whenever I first heard that song — it was forever ago, like in 2000 probably — I just always wanted to record it. I wanted to put it on my last record but it just didn’t fit, but it ended up being perfect for this one, because I needed a waltz anyway.

Chris is just … I don’t know how to describe him. He comes to my gigs, and he’s very fatherly in the advice section, but he is no-shit … like he’ll always tell you like it is, you know? We’ve written together a few times, and I’ll always think, if I can just learn some of the things he does, if I could be half the songwriter he is, I think I would be doing OK. I’m still shocked that he has a song with “hypotenuse” rhymed in it. I mean, who does that?

With your last album, Provoked, the elevator pitch seemed to be that it was all about you moving on after your divorce from your first husband, and finding a new start with Jeff. Is there any particular theme tying all the songs on Trophy together?

I don’t think there’s a theme necessarily, but I do think the record and the content of the record … it’s kind of me grown up a little bit. Well I don’t know if “grown up” is the right term for it, because I was grown up on the record before it and the one before that, too — I’ve been an “adult” on all my records. But I feel like I’m more comfortable now talking about things that are going to bring out emotions in people. Some people may not want to hear something that’s going to bring out those emotions, but to me, that’s my job.

I don’t know how to really describe it, because I didn’t set out to make a thematic record. The last one, yes — that was specifically about, “There’s a light at the end of the tunnel, and here’s why there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.” But this one, I just feel like it covers a lot of bases. There’s new love, old love, and stuff like “Unsaid,” which a lot of my friends who have either lost a parent a friend have heard and been like, “holy shit.” And I didn’t necessarily set out to write a sad song, it just ended up that way — but it’s real.

So I guess that’s what the theme is here: I feel like it’s real shit.

Theme or no theme, I think it really is your best record to date. But I’m actually still really partial to Heartbreakers’ Hall of Fame. On that note … can you still appreciate every record you’ve made?

Oh yeah!

I mean, we both know a lot of artists are like, “Ugh, I hate my first record …”

Yeah. But, no. In fact I just talked to Tommy Detamore about this the other day. Tommy played steel on this record, and he produced my first one. So we were talking and he said, “Man, Sunny, I’m really proud of this record.” And I was like, “Thanks dude! Coming from you that’s amazing.” Because he’s really picky. And I was really thrilled that he liked my record and liked what I did and that he would put his stamp on it by playing steel and all that. Then I said, “But Tom, the thing is, there’s lots of my friends who have first records that they would absolutely die if somebody heard it. But I’m still selling mine at my shows. I’m proud of it, I love it.”

And they’re all really different. That first one was really country, the second one was specifically to try to get songs on the radio, the third one was to prove that I could still make music without a big label, and then this one is … Well, what (producer) Dave Brainard said was is that it’s my “don’t-give-a-shit record. You know, not in the sense of like, “I don’t give a shit, let’s just screw around and make whatever,” but in the sense of …

You don’t have to prove anything anymore.

Right. I mean, yeah … kind of. Basically, I’m just putting songs on there that I think are going to resonate with people. Some songs may not resonate with everybody — like “Trophy” may not resonate with somebody who doesn’t have an ex-wife or who isn’t in a relationship with someone who does. But if they have been through a similar situation … I think they’ll get it.

[…] LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, March 11, […]