By Thomas D. Mooney

Over the past decade, Dave Cobb has produced critically-acclaimed — and award-winning — albums by the likes of Jason Isbell (Southeastern, Something More Than Free), Shooter Jennings (Put the “O” Back in Country, Electric Rodeo, The Wolf), Jamey Johnson (That Lonesome Song, The Guitar Song), Sturgill Simpson (High Top Mountain, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music), Chris Stapleton (Traveller), and Lake Street Dive (Side Pony) among a host of others. Additionally, the Nashville-based producer has albums by singer-songwriters Amanda Shires, Mary Chapin-Carpenter, and Holly Williams all slated for 2016 releases. His discography reads much like a “Best of the 2000s” list.

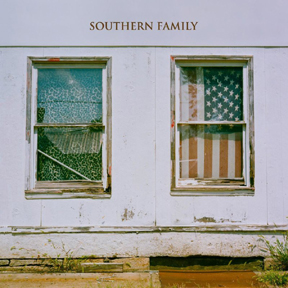

Cobb’s latest project is a concept album called Southern Family (released March 18). Some album titles, they’re as forward as they possibly can be — and Southern Family is indeed a record about family, for family, and made by a family of like-minded songwriters and musicians. It’s comfort food for the soul. The 12-track compilation features the likes of established Cobb collaborators Isbell, Stapleton, and Johnson, along with an assortment of fresh faces — for Cobb, at least — like Miranda Lambert, Zac Brown, and Brandy Clark.

Cobb’s latest project is a concept album called Southern Family (released March 18). Some album titles, they’re as forward as they possibly can be — and Southern Family is indeed a record about family, for family, and made by a family of like-minded songwriters and musicians. It’s comfort food for the soul. The 12-track compilation features the likes of established Cobb collaborators Isbell, Stapleton, and Johnson, along with an assortment of fresh faces — for Cobb, at least — like Miranda Lambert, Zac Brown, and Brandy Clark.

“It’s their record, too,” says Cobb. “I want people to know that we did this together. It wasn’t just me. I felt it was a real community of talented writers and singers being on the same team for a minute.”

Despite so many different voices contributing to the album, Southern Family is held together by its recurring themes of family values, Southern roots, and loss. The vast majority of songs are triggered by specific individuals — mothers, fathers, grandparents, and siblings. These roots run deep, forming a web of old vignettes with gospel overtones, everyday commonality, and personal experiences while growing up in the South. And while Southern Family certainly looks to the past for most of its detail and inspiration, it also feels like a coming of age album in the way it highlights so many of the leading singer-songwriter voices of the new millennium. It’s a harbinger for a New South while recognizing the time tested sounds that make up the South’s rich, organic sound. Like the American flag that drapes its cover, Southern Family’s tapestry is vivid and bright, yet well-worn and comfortable.

Lone Star Music caught up with Cobb to discuss the making of Southern Family, what he’s learned from his experiences working with the likes of Isbell, Stapleton, and Simpson, and his thoughts on producing honest albums based on humanity and compassion.

You’re obviously not making music for the sake of winning awards. But it must feel great that your work is getting recognition by these institutions.

Yeah. I feel really lucky. None of this was set out to win anything. None of that was on the radar when these records were made. We were making records that we enjoyed, that my family enjoyed, and maybe a couple of friends would enjoy. I’m just excited that these records have lived outside our wildest dreams. I’m super proud of them.

Where do you have your Grammys?

They haven’t showed up yet. [Laughs] Probably at my mom’s house. She’d drag me to lessons and everywhere I wanted when I wanted to rehearse with bands or whatever. Or she’d host us when we would do it at our house. I imagine they’ll go to her house.

Speaking of family, Southern Family was just released. That’s not something you put together overnight. How long did it take to get the ball rolling?

It took about a year. Every day I had off, I was in there tracking for Southern Family. It didn’t take very long to get people to agree to do it. It was getting everyone’s schedules worked out. I’m happy they dedicated their free time to get it done. They put in as much as I did. It felt like everybody was happy to be a part of it. I owe them immensely.

What exactly did you tell them when you pitched them the idea? Was there anything you told every individual to think about when writing a song for the compilation?

There was a record called White Mansions. It was written by Paul Kennerley and produced by Glyn Johns. It had Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter on it. I’d been forcing that down people’s throats for years. They were sick of me talking about it. Any time we’d hang out or were just talking, I’d bring it up. That’s where the idea of the concept record came from. So when I asked them about this, they knew where I was already coming from. Secondly, I wanted them to write something very personal to them — something that was about parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters, just something that really meant a lot to them. How they grew up and about those things that were crucial to them.

There was a record called White Mansions. It was written by Paul Kennerley and produced by Glyn Johns. It had Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter on it. I’d been forcing that down people’s throats for years. They were sick of me talking about it. Any time we’d hang out or were just talking, I’d bring it up. That’s where the idea of the concept record came from. So when I asked them about this, they knew where I was already coming from. Secondly, I wanted them to write something very personal to them — something that was about parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters, just something that really meant a lot to them. How they grew up and about those things that were crucial to them.

I was actually going to bring up White Mansions. I’d never heard of it before. It’s kind of a forgotten record.

Yeah. I wish it wasn’t. It is a touchy subject matter on the record, but it’s not about that. It’s about how the record makes you feel and the ride it takes you on.

Morgane and Chris Stapleton’s “You Are My Sunshine” is such a unique take. It’s dark and sultry, yet very warm. Was that something you all developed and created while in the studio or were they well on their way once you became involved?

They were already on that. When they told me they wanted to cut that song for the record, I kind of laughed at them. I said, “Come on. Really? Y’all can be more creative than that.” I kind of buffed at them about it. I play with those guys live sometimes. One time, they threw it on the setlist. They said to just follow them in G. We get on stage and start playing it and they play it like that. I had to apologize extensively about it afterwards because they were so right about it. So yeah, they had already reinvented the song. Later on, I found out that it was on the inside of Chris’ wedding ring. It’s kind of a family thing, too. I think it’s the first thing they sang together when moving into a new, empty house. They pulled a guitar out and sang that version.

I saw them play a few weeks back. When they played it, it was just a magical moment. Probably the best of the night.

I found out today that it’s No. 1 on Spotify (the US & Global Viral 50 lists) — her version. I’m so happy for them.

That’s incredible. A lot of these songs on Southern Family are deeply rooted in family and friends. How much of your own family do you see in these songs?

I think there’s a lot of commonality with everybody’s family when growing up in the South. A lot of times, the church is the centerpiece with everyone’s lives revolving around it. You can hear that in the songwriting. Whether it be Texas, Alabama, or Georgia, there’s a very similar set of values. The themes that runs through it all, they definitely hit home for me. The mentality and mannerisms in some of the songs, they’re a part of everyday life. I think a lot can identify with that.

Jason Isbell’s “God is a Working Man” is right in line with church being the centerpiece of Southern living.

The thing about Jason, whenever he writes a song, when you hear it that first time, it means something to you. My grandmother was a Pentecostal minister. His grandfather was, too. So I grew up in that whole thing. My grandmother always taught me to be kind to everybody, not to judge anyone, and give people a chance. I think that’s a big part of that song. But still, Jason’s songs, it always takes me two or three years to really understand what he’s talking about. He cuts so deep with a pen. It may seem light, but when you start digging into the lyrics, you realize what it is he’s really talking about. I’ll have to tell you what it’s really about in two years. [Laughs]

You worked with about half of the folks on Southern Family before. Were you hesitant to bring in new voices and people you hadn’t recorded before?

No, I was excited about it really. Miranda Lambert is a great example of that. I’m such a huge fan of hers. I always thought she stood for authenticity and made really great records. She was on the wish list since day one, but it didn’t seem possible. She’s a superstar. I didn’t know her and no one I knew really knew her that well. So it just kind of seemed out of the realm of possibilities. But I ran into her one night and she gave me crap about not being asked to be on it.

Although you’re not a recording artist and putting out your own albums, do you think this is maybe the beginning for you in a way?

I don’t think so. If I could sing, I’d have done an album a long time ago. I’ve always been in bands. I do write some on these records — not necessarily this record, but I do write on some. I played a lot on Southern Family. I do get that creative energy out in that way.

How about doing more compilation albums like this, where you’re leading the charge with subjects and themes you care about? I know you’re just a few weeks off from releasing Southern Family, but are there more ideas you’d want to dive further into?

I think after this one, I’m done with them for a while. There was really a lot of heart and sweat put into the making of the album. It has taken a lot to get this one finished. We’ll see though. Crazier things have happened.

You’ve talked about how the first thing that draws you to artists are their vocals. Everyone you’ve worked with, they have strong, distinct voices. What’s the next thing that you look for in an songwriter or band?

Yeah, it starts with the voice. That’s what draws you in. But secondly, it’s about the intangible qualities of them. If they’re unique and standout. They have to carry themselves in a certain way. I have to feel honesty in their intent, too. The records they like and where they want their careers to go. I think subliminally, we’re all in line with one another — our ideas of what’s right and wrong.

Do you need to get to know these people before stepping into a studio and recording them? Is being friends sort of a requirement?

Sometimes being in the studio, you get to know them. [Laughs] Generally though, it does start out as being buddies before.

So much of producing an album is helping an artist execute whatever vision they have for a selection of songs. It’s helping them achieve that vision. But how often do you feel you’re helping them go outside their comfort zone and grow?

I think for the most part, everybody is on the same page. We’re not really going outside of comfort zones. I think one thing that is maybe outside of comfort zones is keeping tracking vocals. When you’re running the song down and not fixing anything. I think I talk people into that pretty regularly. As it happens, they’re like, “I think I can do that better.” Later on, they realize that the intent was there on the take going down. Sometimes you get too cerebral about recording and it just misses the heart. I’m real keen on keeping mistakes and keeping that raw feeling. I think people connect to that humanity.

What’s the typical day for you when recording? Are you trying to keep it to a specific schedule or is it more free flowing than that?

Yeah. We usually start after lunch. Somewhere around 1 o’clock. But for Stapleton’s Traveller record, it was his idea. We’d get there around noon, goof off, drink a little bit, order some food, order some more food, drink a little bit, goof off some more, tell some jokes, and listen to music. We wouldn’t start recording until 8 or 9 o’clock. But we’d get three masters every night. That was for him really. I learned a lot from Chris about when the perfect time to record was. It’s really hard to put music on a clock and expect it to roll. You’ve got to let it flow. When you think it’s right, that’s when you got do it.

Yeah. We usually start after lunch. Somewhere around 1 o’clock. But for Stapleton’s Traveller record, it was his idea. We’d get there around noon, goof off, drink a little bit, order some food, order some more food, drink a little bit, goof off some more, tell some jokes, and listen to music. We wouldn’t start recording until 8 or 9 o’clock. But we’d get three masters every night. That was for him really. I learned a lot from Chris about when the perfect time to record was. It’s really hard to put music on a clock and expect it to roll. You’ve got to let it flow. When you think it’s right, that’s when you got do it.

These days, I imagine it’s where you’re recording every day. But earlier on in your career, was it more sporadic on the when and where?

I always tried to keep busy. I’m not too good with days off. If I had a day off, I’d invent something to do. I’ve always kind of killed myself in the studio. I’ve loved it so much.

A lot of the artists you’ve worked with, in a way, they were unknown to the masses. People knew about them in the country or Americana realms, but they didn’t necessarily have national recognition. Did that make it easier to record, since there was very little outside pressure?

Yeah. Like Sturgill’s first couple of records, the world wasn’t waiting for him. We went in there just to do it. It was on our own schedule. They were quick and we didn’t think twice about it. It was a flow of consciousness kind of thing. It was definitely nice to be under the radar a little bit.

Do you believe in momentum when recording a record?

Yeah. I like to record records really fast. The beginning of something may be when you’re most excited about it. The longer it goes on, the less excited and the less heart may be put into stuff. I like making records super fast so you never get the moment to think too much about it.

What’s been the longest you’ve taken to record an album?

Probably about a month. That’s just too long for me. Maybe six or seven weeks total. I like two-week records.

Is it just because you’re able to create a moment in time? It’s easier to capture what a band or artist sounds like in a specific time?

Yeah. I like to go with your first instinct,s too. Whatever you’re feeling first, just go with it. Don’t question yourself too much. If it’s wrong, you’ll figure out at the end. Sometimes people get into rehearsing six months before a record. Then demoing the shit out of it. Then pass those demos around and get opinions. Then by the time you’re ready to record, it’s antiseptic. They’re sick of the songs themselves. They’re past that point of excitement. They recorded their best vocals when they cut the demo. And then they’re chasing the demos. [Laughs] There’s a lot of backwards ways to make records. We do all have the ability to make records in our rooms. Sometimes that’s not the best thing. Sometimes it’s the perfect thing. But, it can kill the excitement of walking into a studio with people and recording that first time. It can be missed.

So many artists, when they look back at older albums, they’ll nitpick or find flaws in the work. It’s kind of in their nature to think and feel that whatever they’re working on in the present is their best work. Is that something you feel as well, or do you think you have a little more distance from them?

I think every time an artist writes a new song, it’s their best song. I think that’s exciting. Even if it isn’t, that’s the time to record them. You get that excitement on tape. I feel I’ve been so fortunate to work with these great artists. They have really great judgement on their own songs. They have great judgement of how they want to make a record and how they want to be perceived. I haven’t had one of these great artists bring in a big stinker yet.

You said one of your intentions for Jason’s Southeastern was for it to feel as though he was playing in your living room. He ended up recording a few of those songs in your kitchen. Was that just part of helping create that intimacy, by putting in spaces that were …

Normal?

Yeah. An area that was part of every day normalcy.

That was definitely part of it. When we were talking about making the record, one of the things I suggested was that I’d love to record in some caves. [Laughs] Now it sounds like a terrible idea, but he loved the idea of it, too. Luckily, he had his own label so there wasn’t anyone telling us we couldn’t. But he was getting married around the time of recording, so my living room and kitchen wound up being the cave. It was our substitute. A lot of it was because we were recording in the studio in the back of my house. That’s where we’ve done a lot of these records. The vocal booth we were using, it was really tiny. He’d stretch his arms out and feel a little confined. The only way I thought we could free him up a little was to get him in the kitchen. That’s how that happened. It ended up sounding so great because he wasn’t being influenced by anyone. Nobody was looking at him. It’s just him by himself looking out over the Nashville skyline.

That was definitely part of it. When we were talking about making the record, one of the things I suggested was that I’d love to record in some caves. [Laughs] Now it sounds like a terrible idea, but he loved the idea of it, too. Luckily, he had his own label so there wasn’t anyone telling us we couldn’t. But he was getting married around the time of recording, so my living room and kitchen wound up being the cave. It was our substitute. A lot of it was because we were recording in the studio in the back of my house. That’s where we’ve done a lot of these records. The vocal booth we were using, it was really tiny. He’d stretch his arms out and feel a little confined. The only way I thought we could free him up a little was to get him in the kitchen. That’s how that happened. It ended up sounding so great because he wasn’t being influenced by anyone. Nobody was looking at him. It’s just him by himself looking out over the Nashville skyline.

You did the last Whiskey Myers album, Early Morning Shakes. I spoke to them about the album around the time it was released. One of the things they mentioned was how they intentionally went in with the songs being loose sketches rather than fully formed. A lot of the writing was done during the recording of the album.

Yeah. I kind of like doing that to people. I like when people come in with things that aren’t quite settled. If you work the songs out too much before coming into the studio, you can lose some of that magic. That’s one of my things. I like when people come in and it’s kind of raw and no one knows what we’re going to do. I went to this thing at the Country Music Hall of Fame six or seven months ago that was about Sam Phillips. It was about him cutting all these records with Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and everything. He said that at Sun Records, they used to walk in every day without a plan and walk out with a master. They didn’t know what songs they were recording or who was coming in. They just made it up. I think that’s what it’s supposed to be like. It’s supposed to be like this fairytale land. I like to not have too much of a plan. It scares the crap out of a lot of people. We’re real fortunate to get some of that danger on record.

What’s been the song or album that you think took the strangest turn?

Sturgill’s Metamodern is a good example. We had four days off. He came in and we started going for it. I think we started pulling some old tricks and some crazy ’60s production techniques with tape delays. We were making each other laugh. From there, we just kept pushing the boundaries more and more. We weren’t thinking of it being some kind of statement to the world. We were just having a blast. I think you can hear that on tape. We didn’t think anyone was going to give a shit about it. But we’re so happy it went the other way. [Laughs] It definitely was wild.

Yeah. I think a lot of people loved the idea of that album as a whole. Even though we’re in a digital age, there is that resurgence of vinyl and all things vintage. That’s one of the biggest reasons I think people connected to that album. It was an album that took you on a journey.

I think more than vinyl, I think it’s because people want records with humanity on it. Everything is done so with this paint by numbers mentality. Old records in general, they had real humans playing in a room together. They’re not real edited. You can hear people interact on them. I think that’s what people are drawn to more with vinyl than the actual vinyl itself. The great thing about vinyl is that it’s tangible. You can hold it. Whereas with digital, it lives in a cloud. It’s not quite the same experience. I do love it, too, though. I love having Apple Music and Spotify. I love having my library anywhere I go.

You mentioned earlier about cutting a bunch of these records at your home studio. Now though, you’re over at RCA Studio A. Obviously, it’s a much bigger space to work out of. There’s so much history there. Has the responsibility sank in?

It is a powerful place. You walk in and you know you better act right. It is a lot of weight. If I thought about it too much, it’d be a heavy load. [It helps that] I’ve recorded there a lot already. A lot of Southern Family was done there. Stapleton’s Traveller was done there. We had such a good time then, I think that’s when I really fell in love with the place. I loved it before, but being there for the length of time were when we did Traveller, cutting up and letting the place soak in, and acting that it was like the back of my house, I think that’s really when I fell in love with it. We feel really attached to it. It’s definitely a heavy load, but I’m excited about the challenge.

So much of the narrative is that you, along with many of the artists you’ve recorded, are “saving” country music — or at least preserving it. It’s not as though you’re making music and records strictly for this notion that country music needs saving. But at some point, perception can become reality. I mean, it’s not as though you’re living in a bubble and not hearing these things.

I think we’re just making records that feel good to us. I actually think it’s people who are saving country music. It wouldn’t be me or anyone else. It’s people responding to honest records, whether I or someone else did them or not. There’s a lot of great art out there. I think it’s the record buyer who is saving country music. We just go in and make records. We see where they lay afterwards.

The “Jimi Hendrix Of The Violin”, Lili Haydn Explains What Life Has Dealt Her And What Her Album “LiliLand” Is All About