By Richard Skanse

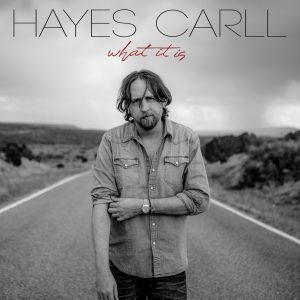

The Hayes Carll pictured on the cover of his new album, What It Is, looks every minute of the eight years he’s aged and grown since the last time he showed his mug on a record sleeve, and he wears it well. In stark contrast to the comically dazed-and-confused, star-spangled hangdog rube pictured on the cover of 2011’s KMAG YOYO, looking for all the world like an alien abductee unceremoniously dumped far from home on an urban rooftop, the 2019 model Carll of What It Is is clearly a man who knows exactly where he’s been, where he’s going, and most pertinently, where he is now. Drop him anywhere — in the middle of a desert highway, at the anything-can-happen brink of a new relationship, or on the perilous edge of the political divide fracturing his homeland like a fault line — and he takes it all in, rolls up his sleeves, and effectively says, bring it on.

Now to be fair, the Carll who made KMAG YOYO — and 2008’s Trouble in Mind, 2005’s Little Rock, and even 2002’s Flowers and Liquor before it — had his proverbial shit together far more than appearances and his self-deprecating sense of humor often led on. From the git-go of his recording career, if maybe not quite the first time he tried his luck playing covers for drunken tourists and shrimpers along the Texas Gulf Coast, it was pretty apparent that Carll was bound for inclusion amongst the ranks of the best Texas and Americana songwriters not just of his generation, but the one before. To wit: Scads of young guns over the last 15, 20 years have talked Ray Wylie Hubbard into co-writing with them, but Carll’s one of only a very select few who came away from said meetings with songs good enough that Hubbard wanted to record them himself — with the verdict still out on whether “Drunken Poet’s Dream” is more of a Carll song or a Hubbard song (call it pretty much a draw, advantage whoever’s version you happen to be listening to at the moment.) Equal parts poet and jester, Prine and Silverstein, Carll has long been the thinking man’s everyman: a disarmingly relatable, down-to-earth troubadour quick in wit and fit to stomp and holler with the best rabble rousers in the business, but just as gifted in the subtler side of working heartbreak and pathos into classic-country worthy weepers (most notably “Chances Are,” which fellow Texan Lee Ann Womack parlayed into a Grammy nomination) and listening room gold (pretty much the whole of his last album, 2016’s Lovers and Leavers).

Now to be fair, the Carll who made KMAG YOYO — and 2008’s Trouble in Mind, 2005’s Little Rock, and even 2002’s Flowers and Liquor before it — had his proverbial shit together far more than appearances and his self-deprecating sense of humor often led on. From the git-go of his recording career, if maybe not quite the first time he tried his luck playing covers for drunken tourists and shrimpers along the Texas Gulf Coast, it was pretty apparent that Carll was bound for inclusion amongst the ranks of the best Texas and Americana songwriters not just of his generation, but the one before. To wit: Scads of young guns over the last 15, 20 years have talked Ray Wylie Hubbard into co-writing with them, but Carll’s one of only a very select few who came away from said meetings with songs good enough that Hubbard wanted to record them himself — with the verdict still out on whether “Drunken Poet’s Dream” is more of a Carll song or a Hubbard song (call it pretty much a draw, advantage whoever’s version you happen to be listening to at the moment.) Equal parts poet and jester, Prine and Silverstein, Carll has long been the thinking man’s everyman: a disarmingly relatable, down-to-earth troubadour quick in wit and fit to stomp and holler with the best rabble rousers in the business, but just as gifted in the subtler side of working heartbreak and pathos into classic-country worthy weepers (most notably “Chances Are,” which fellow Texan Lee Ann Womack parlayed into a Grammy nomination) and listening room gold (pretty much the whole of his last album, 2016’s Lovers and Leavers).

But by his own admission, Lovers and Leavers was a bit of a departure for Carll: a conscious effort to see just how open and personal he was willing to get with his songwriting, sans the protective armor of humor, composite characters, or even catchy sing-along choruses to hide behind. From both a creative and personal perspective, it was an entirely appropriate approach for what was in effect the then-40-year-old songwriter’s “divorce album,” but it was a bold gambit all the same. While the quality of the songs proved that naked honesty was well within his artistic range, the intensely introspective focus and disciplined commitment to theme meant that it was also, by design, kinda the first Hayes Carll album that really wasn’t a whole lot of fun. A worthy and intriguing addition to his catalog, certainly, but arguably not the best representation or full dimensional portrait of the artist doing all that he can do.

What It Is, on the other hand, is all that and more — packing just about everything even the most demanding Carll fan could ask for without so much as a hint of play-it-safe pandering. The swaggering confidence and freewheeling sweep of KMAG and Trouble in Mind is back in spades, buoyed by the joie de vivre of a man unabashedly inspired by a new muse: specifically, fellow acclaimed singer-songwriter Allison Moorer, his fiancé, co-producer, and co-writer on half of the dozen new songs. But with the notable exception of the giddy mash note “Beautiful Thing,” this is hardly an album defined by carefree, head-in-the-clouds abandon: it’s Carll’s unflinching, white-knuckled ride across the treacherous landscape of “Times Like These” and straight down into the “American Dream.” Along the way, he balances poignant observations both societal and personal with a generous helping of whip-smart satire, gamely trolling all manner of hypocritical finger pointers, a certain unnamed whiner-in-chief, a fragile patriarchy prone to bruising like an over-ripe peach, and even goddamn 21st century Nazis.

Doubtless Carll never dreamed he’d ever have to take on those guys when he first signed up for duty back in his salad days on Crystal Beach, but well, 2019 is what it is and a gig’s still a gig. And unlike his bewildered, “how did I get here?” protagonist in “KMAG YOYO,” he’s right where he wants to be, calling his own shots and not backing down.

Before jumping into What It Is, first tell me where you’re at.

I’m in New York. Chelsea.

I’d heard you’d been splitting time between there and Austin since meeting Allison.

Well, actually I split time between New York and Nashville now. I left Austin about a year and a half ago, and I’ll be in Nashville full time come May.

Wow. My bad for not knowing that. Have you lived in Nashville before?

No. I’ve never lived anywhere other than Texas, except for in college, when I lived in Arkansas, and I also spent about six months in Croatia around 2000. But with the exception of that, my zip codes have always been in Texas. Lived on the beach for a number of years, and then lived in the Conroe/Woodlands area for a couple after that, and then I was in Austin for 11 years, since I guess about 2006. So this is my first time to have a drivers license from any other state. I’ve got a Tennessee license now, which is a bit surreal.

Probably not as much as adjusting to New York, though. How’s life in the big city treated you? I lived there for five years in my 20s, and I’m glad I experienced it, but I don’t miss it much.

Yeah, it’s challenging, especially with kids. I wish I’d done it as a younger man. It’s an amazing, one-of-a-kind place, but I’m at a point in my life where I appreciate a good yard and some quite way more than I do all the bells and whistles that New York has to offer.

Were you there for the birthday you just had? (Jan. 9)

Yeah. Right before that I went and did Steamboat MusicFest. Allison tells me that a birthday “week” is a thing, so I tried to make that a part of it, but I got out of there the day before my birthday and just tried to take it easy. She took me to dinner at one of my favorite restaurants here in New York, and I just had a relaxing day.

I’ve actually only been to Steamboat once, and that was 17 years ago. Do you go every year? Or does it just seem like it?

[Laughs] I’ve done it … seven times? I’m not exactly sure. I started going I think in 2004, 2005, and did it on the regular for a while, but it had been four or five years since my last time. For me, it’s just always been a good way to catch up with a lot of friends in one place. John Evans was there this year, and Corb Lund, Bruce Robison, BJ Barham, Randy Rogers, Jamie Wilson — just a lot of folks that I don’t get to see a whole lot of, I get to see them all at the same time. And of course there’s also, you know, like 4,000 Texas music fans who scale the mountain, so it’s a good way to reach a lot of those folks in one weekend, too.

The whole “Texas music” scene has really evolved a lot since my Steamboat trip in 2002. Back then, Pat Green and Cory Morrow were very much the kings of the hill. There was always an Americana contingent, too, but artists like you were more on the fringe, like the outsiders smoking at the back of the parking lot with older cats like Ray Wylie Hubbard. But these days it seems like it’s the Americana misfits who really define the scene. Would you agree?

Well, I feel like we found our place in a way. I think in those early days I was just trying to find anybody that would listen to my music. The Texas music scene was exploding, and you know, some of it I totally got, and some of it I didn’t, but what I saw was that the people loved it, and I just tried to make the music I wanted to make and find a home for it. It took awhile, but I found ways to navigate my way and build up a crowd that appreciated what I did. The power of radio and relentless touring can go a long way as far as getting people to come over to your side, and what’s interesting about it is, they came from all over the map: I had the folky songwriter fans, and I had the Texas country and Red Dirt fans as well. As for the scene as a whole, though, I think a lot of the elements of that early Texas country craze are still there — it’s just that some of the names have changed! And I think that while a lot of the more fringe singer-songwriter type guys and girls are maybe a bigger part of the scene now than in the beginning, they’re still a little left of center. But there’s still room for all of it, and I’m just glad that the stuff that I do has attracted an audience and a lot of people that I like and appreciate have been able to, as well.

Speaking of the stuff that you do, I remember thinking that your first two albums, Flowers and Liquor and Little Rock, were both a cut above a lot of the albums I was hearing from new Texas artists back then, but like I imagine was the case with a lot of your audience, it was Trouble in Mind and especially KMAG YOYO that really grabbed my attention. I just loved the range and attitude of those records, and especially the wit. Which is why I admit that Lovers and Leavers took a little longer to grow on me. It’s not that I only liked your funnier, rowdier songs — I always appreciated that you could write more serious stuff, too, and recognized the quality of the songwriting on that album. I just missed the even mix of the two. Which is my long way of saying that I really love What It Is, because that balance is back. It just seems to show a more well-rounded picture of what you can do.

Yeah, I think it does. And it feels like everything kind of culminated in this in a way, if that’s the right way to describe it. You know, Lovers and Leavers was a departure; it was about was a time and a place and where I was at. And it was also something that I needed to do to prove to myself creatively that I could do. And I’m glad that I did it, but I understand the reaction that some people had to it …

Well, I think my own reaction to it surprised me, at least with hindsight. Because I’ve done a lot of interviews with guys like Ray Wylie and Robert Earl Keen where we’ve talked about that frustration that’s sometimes there, probably more-so in Keen’s case, when some of their more serious songs tend to get overlooked in favor of their more obvious crowd-pleasers, and I’ve always been right there in agreement with them. And I’m also invariably a fan of records where artists stray outside of their usual comfort zone and challenge audience expectations. And yet there I was listening to this really well-written and intentionally very different Hayes Carll album for the first time, and all I could think was, “Dammit, where’s the ‘KMAG’ or ‘Stomp and Holler’ on this thing?”

[Laughs] Well, even as an artist … when I go to watch shows, I’m well aware through 2,000-plus performances of my own what it’s like to be onstage and wrestling with the crowd expectations of what you do; but when I’m in the audience, that’s rarely what I’m thinking about. I’m thinking about what I want to hear! And so I can see the same thing as a music critic and a fan as well. And I knew that record was not going to scratch that itch for a lot of people. But it scratched the itch for me, which at the end of the day was the most important thing for me to do at the time. And because I did do that on Lovers and Leavers, when it came time to making this one, I felt like I could come back to the variety — I didn’t feel like the need to create such a specific time and place as I did on that last record. And that opened it up to where I could just write the best songs that I could write, wherever I was going creatively. Whether that was about my relationship, whether that was about where I was in my life, whether it was about whatever was going on in the world around me, I could just have fun and be engaged with that, and then musically go in and experiment and sort of push myself in whatever direction it felt like the song required. So, we were pretty wide open. And at the end, when I finished it, I did think of Trouble in Mind and KMAG. I thought, these are records where there’s light and heavy, there’s fun and there’s serious; where I felt like I can be poetic and hopefully profound at hopefully the same time, and on the very next song be light-hearted and have a completely different energy. And that’s fine, because I love all of it. I love trying to hold an audience’s attention with just an acoustic guitar and my lyrics, and I also love to just tear the shit out of a roadhouse and honky-tonk it up. And I love everything in between, too! There’s so many different ways to make music and so many different levels and things you can reach emotionally, that it’s really fun to not have any limits on any of that. And I feel like on this record we didn’t have any limits.

You mentioned Lovers and Leavers being a departure, but it was more than just a tone and musical thing. I remember you talking in interviews at the time about how those songs were really some of the first you’d ever shared or recorded that were unabashedly personal, as opposed to more outward looking. But on this album, those two streams seem to have really merged.

Yeah. I think that’s what I meant about this being a culmination of the past stuff. On previous records, I’ve had personal stuff in there, but it wasn’t until Lovers and Leavers that I really started showing it; in the past it had really come out in sort of more subtle ways, or through another character. So part of what Lovers and Leavers was for me was figuring out how much I could show of myself, figuring out how much to cover up or not. And on this one, there’s a few character driven songs, but most of them tie in pretty directly into something in my life. And that feels like growth for me: knowing that I can do that in a way that I couldn’t do before, but also that I don’t have to be really heavy handed or overly serious about it at the same time. It can be there when it needs to be, but I can also have fun with it, because my life really isn’t that heavy handed or serious most of the time. [Laughs] I mean, I have my struggles and I have shit I’m trying to figure out, and I take it seriously and it’s important to me — but I don’t necessarily need the audience to be my therapist all the time, and whatever ideas or observations I have, I think there’s ways to put them out there in an entertaining and engaging way.

There are also a handful of songs on What It Is that are pretty overtly, for lack of a better word, “political,” which unless I’m mistaken is a first for you. You obviously flirted with that arena in “Another Like You” from KMAG, but I can’t imagine anyone ever taking offense at that song because it was so damn funny, and you really took the piss out of both the liberal and the conservative characters pretty equally. But between “Fragile Men” and “Wild Pointy Finger” and a couple of key lines elsewhere on this album, it’s pretty clear which side of the political divide you align with. Have you ever been caught in those “shut up and sing” crosshairs?

Well, I’ve always been aware of it, for sure. And I think early on … the reason I started writing and singing and playing songs, at heart, was because of Bob Dylan. Because I heard somebody singing “Blowing in the Wind” and “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall,” and I thought, that’s life-changing music, that makes a difference in the world. I mean, I love music, and I love primarily country music — that’s always been my draw and I sing it for fun and it’s meaningful. But there’s always been a part of me personally and creatively that’s very drawn to social issues and social justice and politics, too, and it’s an interesting mix that’s always been tricky as a quote/unquote “country” singer. Like I said, I spent a lot of time just hoping anybody would think I wasn’t terrible; that was sort of my main goal for a long time, so the idea of hitting people over the head with my politics was never really a front and center concern for me. And I don’t think you need to, either, unless you need to! [Laughs] So what I’ve done over the years is, I think I’ve been subtle about it in most cases; anybody looking through my records for clues about where I lean politically, they’re for sure there — but preaching to the choir has never held a lot of appeal for me, and just lecturing people hasn’t, either. I’ve always been drawn to the Todd Sniders or Randy Newmans or John Prines, people who can use humor to relay a relatable sentiment about how they feel, and so that’s kind of how I’ve always approached it. And I don’t think I’ve really strayed too far from that on this record; I think there’s three songs that have some kind of political reference in there, and I have a hard time imagining people getting too upset about what it is that I’m actually saying.

Yeah, but … never underestimate the easily offended.

Right. Which I’ve really come to realize lately. You know, I played that Beto O’Rourke event in Dallas, and I realized that no matter how you frame something, if you take any side politically or socially, these days there is a level of vitriolic animosity and anger and a certain group of people who are always going to try to bowl you down and make you back up on any of your beliefs. And that’s what songs like “Times Like These” are about, and especially “Fragile Men.” I wrote that one with this artist named Lolo, and it was originally about patriarchy, like about some experiences she was having in the music business as a woman. But then we came back and rewrote it a week after Charlottesville happened, and the idea that we were going for was, we wanted to mock these men and make fun of Klan members and neo-Nazis and white supremacists, because I think they’re pathetic. So we recorded a demo of the song with her doing the vocal and made a little video showing those people, just trying to make them look ridiculous. And I was really shocked by the amount of blowback we got from people. We’re now in an age where universal condemnation of racism and Nazis, it’s not universal anymore! So that was really when I knew I had to decide, “Am I going to let people control what I put out, or not?” And I just don’t have any desire to move backwards or to support anything going backwards culturally or socially. While there might have been a time where I felt like I had to please everybody, or hide my opinions, I just don’t feel like that anymore; that time is past. So letting people know what side I’m on of an issue, I’m getting more comfortable with that, and whatever happens, happens. But at least I’ll know where I stand.

This is stating the obvious, but it is pretty hilarious that you can write a song about fragile men literally called “Fragile Men,” and then have a bunch of fragile men take such strong offense to it.

The irony was totally lost on them! I mean, I had like 2,500 comments on my Facebook, and about every fifth person would point out exactly that: “Your feelings are hurt because he wrote song called ‘Fragile Men’ about Nazis and how ridiculous they are, and you’re going to come onto his Facebook page and complain about it?” But what are you going to do, you know?

Or as another song goes: “What would Willie do?” I mean, the amount of blowback Willie Nelson got for playing at the Austin Beto rally was just mind blowing.

Exactly. And I remember making a post when I was going to go play a Beto event, just saying something like, you know, “politics aside, I like that this guy encourages discussion and appears to be open minded about all sides. Whether you agree with him or not, or even strongly disagree with him, that’s fine; but the very basic idea of being able to have a civil conversation with your neighbor is really important to me, and that’s why I’m supporting him. And you may think I’m full of bullshit or whatever, but we should be able to have a discussion about that as Texans, as citizens, as neighbors.” And what I got was not only a ton of blowback, but I also had a guy come back and say “I hope somebody Dimebag Darrells you!”

Yikes.

I mean, that I say that I support inclusion and being able to listen to each other, and the response is “I hope you get shot onstage …” — what are you going to do with that? Well, what I don’t feel like doing is shutting up in the face of that. And all I’m saying here in my music and the new songs is that that troubles me, that mentality that we’ve got these days. And “Fragile Men,” whether it’s sexual abusers or racial dividers, I am not supportive of you and I am going to make fun of you, because I think you’re bullshit. So if anyone has a strong opinion about either one of those things being a problem …

Bring it on.

Yeah. They can have at it.

TIMES LIKE THESE: “We’re now in an age where universal condemnation of racism and Nazis, it’s not universal anymore,” marvels Carll of the early blowback he got for “Fragile Men.” “So that was really when I knew I had to decide, ‘Am I going to let people control what I put out, or not?'” (Photo by David McClister)

Switching gears completely, one of my favorite songs on the album is “Be There,” which isn’t political at all. There’s just a fatalism to that one — “you say you will, but I know you won’t be there” — that’s really heartbreaking and relatable, but it seems at odds with where you’re at in your life right now. Is that one personal at all? Where did it come from?

That one was actually just three people getting together to see how well they’d work together writing a song. So it wasn’t something where I went in with this theme or idea for the record or anything. Allison had been writing with Adam Landry, who used to be in her band, and he also played on my Little Rock record but I hadn’t seen him much over the years. But he’s just a really great musician and they’d written a song and recorded it that day, and I was like, “I’d like to try that, to go in with somebody who could actually make a track out of what we’re doing, so we can experiment not just lyrically but actually put some drums on it and bass and keys and guitar …” Because he can do all that stuff. So Allison was sort of the consiglieri, she brought us together, and then we all just sat around, going “does anybody have any ideas?” And I had a notebook with this line in it, “You look like a tragedy that just hasn’t happened yet.” And they both perked up when I read that one and said, “Let’s write that story, whatever it is.” It ended up being about expectations not being met in a relationship, but still not being able to let go, or holding onto those expectations even when you know that you’re going to be disappointed. And it gave us a chance to use the term “belhevi,” which is one of my favorite words. It means literally “heavy belly,” and it’s this feeling of sadness that you get like when the seasons change or feel a sense of loss. I think it’s French Cajun, though I may be wrong about that. Anyway, I just love the word, and that we could work it into a song made me really happy.

You actually co-wrote half of the songs on this album with Allison, which I think is kind of refreshing given that songwriter couples apparently don’t write together as often as I would think they would. Amanda Shires and Jason Isbell have written some very good songs together, but she told me once it’s pretty rare for them to co-write, and I don’t think Kelly Willis and Bruce Robison ever really write together, either. And it always surprises me because, if you’re open to co-writing with anyone, why wouldn’t you want to write with the person who not only knows you best but also happens to live under the same roof? Did you ever have any hesitation about working with Allison, or did you know you’d click on that creative level from the start?

I didn’t know until we did it. And it took awhile, I think. I mean, we started writing together really early on just as a fun way to stay connected and stay in touch: writing poetry to each other, haikus … and I can’t remember what it’s called, but there’s a Japanese form of writing where one person writes one line and the other person writes the next line. So we would do things like that, and it was just to get to know each other and get to understand each other creatively and express our feelings. But as a songwriter, co-writing has always been tricky for me, or can be, and Allison and I have different styles, or different approaches. She’s really disciplined and has a really strong point of view, and she’s really poetic and creative, but she comes from different influences than I do. So I think there was a part of me that was like, “I don’t know if this will really work, what you do, what I do …” But then as we got to know each other better and I realized how talented she was, and what an incredible asset she was, I really embraced it. It just took me awhile to feel comfortable showing myself to her. But I guess at the end of the day, yes, it’s a blessing, and she’s my first reader. So when I have an idea, I take it to her. I think of like, Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennen; I think she’s a co-writer on every one of his songs, and I have no idea how that actually works for them, but Allison’s my creative partner. She’s my creative partner in life. We have projects that we work on separately, but she’s the person who’s opinion I go to first or look for first, and she just brings a different point of view and a tremendous skill and depth to everything she does. So yeah, why wouldn’t I take advantage of it? Especially when I’m rumbling along, stuck all the time — it takes me 10 years to write a song sometimes. And she’ll just come in, kick me in the ass, throw out a couple of lines and then it all comes together. So it’s been great for me.

I think it’s funny that one of the songs you co-wrote together was “Beautiful Thing,” which is basically like your ode to her. I presume it wasn’t Allison who went, “Let’s have a line in there about how great I looked in that skirt!”

[Laughs] Yeah. That one started with just a music track I had, and that hook, “It’s a beautiful thing.” But I didn’t know how wide of a lens I was going to take to the story, and I didn’t know what the story was exactly. So I played it for her, and it was one of those things where she really helped me hone in on it, and said, “Just tell the story of us.” So I said, “Ok, that’s easier said than done in five verses, or a couple. How am I going to do that?” So we sat down and kind of went through and picked some of the highlights from our early days, and turned it into a song. It took a minute, but it was a fun exercise. It makes me smile every time I hear it.

You’re not married yet, are you? Just engaged?

Yeah, we’re engaged.

So what’s the May 12 date mentioned in the song? In the lyric it’s framed as a memory, but is that going to be the actual wedding date?

Nah, that was arbitrary; there was a time when we thought that might be the day, but it changed. But Dec. 22 didn’t have the same ring to it! But we do have a date. We’ll be getting married this year.

Well, congrats in advance. Going back to the subject of songwriting, though — if you take Allison as your creative partner out of the equation, is writing a chore for you? You mentioned getting stuck all the time, which I can relate to more than when some people talk about how much they love to just write and write and write. Is it always hard for you, or does it ever really just flow?

I enjoy it. But I have a really hard time with my attention, staying focused, and I also have a really hard time staying in the moment. So things that … when I write, what I like to do is, I’ll get a guitar, and I’ll turn on my iPhone these days, and I’ll just make something up. And that’s the easy part: I can sing for maybe three minutes, and there will maybe be a good line in there, a cool melody, and maybe parts of a chorus. Some passes I’ll get more out of it than others. And I’ll take that, and I’ll listen back to it, and I’ll say, “That’s great!” And I can see where it’s going to go and I can see what it will be, and I can see how it will feel to play it live and to listen to it on the stereo, and I can feel what people’s reaction to it will be. And then I’ll see the award that I’m going win for that and all the money I’m going to make and then how great my life’s going to be after that. So that’s where my mind can often go, but the only problem is the actual work of writing the song is yet to be done! [Laughs] I’m so disengaged because I’m thinking down the road about what it’s going to be like, instead of being in the moment and actually writing it and being engaged with the work. That’s always been my issue, and one that I’m finally becoming aware of and addressing. So I guess to answer your question: when I’m engaged, it’s a really fun process. But for me the trick has always been to try to stay engaged, because I do have a tendency to fantasize about anything except where I am. And that’s what I’m working on these days, creatively as well as just with life in general: how to be present and engaged with whatever it is I’m doing, whether it’s writing a song or going to the grocery store.

Has that become even harder now that you’ve actually had some of those daydream fantasies about your songs come true? Your song “Jesus and Elvis,” from this new album, has already been covered and recorded by Kenny Chesney, and Lee Ann Womack was nominated for a Grammy for her cover of “Chances Are.” I would think a taste of that is bound to affect the creative process on some level.

Well, it’s there. But I feel like I don’t really have much control over that stuff; I didn’t have any control over making those things happen, they just happened. So it’s exciting to me, and it’s exciting to think about more of it happening, but there’s only so much I can do about stuff like that. But you know, the working of one of my own records and my own career, that’s easier to get sort of lost in thinking about, because I can control more of it. I can determine what I put out into the world, I can determine how hard I work at it, and I can observe what’s happening and the reaction stuff gets. I think, from early on, those things really affected my life, because I went from having no money and no career and that being tough, and then realizing that with each record that things got a little bit better. Like it got to a point where I could tour in a minivan, and knew that with the next record, I could tour with a 15 passenger, and with the next record I could afford a Sprinter. And those things matter, because it’s your quality of life, it’s what you do every day and how you provide for your family. So it’s hard not to think about how what you write on this day is going to affect your life and career, and it’s hard to think about that and be at the center of your creative space. But like I said, I’m working to find that balance, while also trying to do things with integrity. I want everything I do creatively to be done with integrity: to make sure it’s something I can believe in at the time and really stand behind.

[…] talks about “What It Is” and what it takes to take a stand in times like these. (From LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, Feb. 17, […]