By James McMurtry

(LSM May/June 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 3)

[EDITOR’S NOTE: On the first night of this year’s SXSW, I cornered Tamara Saviano, producer of the Grammy-nominated This One’s For Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, and asked her if she’d be interested in doing an interview with Clark for LoneStarMusic about his new album, My Favorite Picture of You. Between the tribute album and the hundreds of hours she’s spent researching the definitive Clark biography she’s writing, Saviano’s been immersed in all things Guy for quite some time now, and I thought she’d bring an unbeatable level of expertise and insight to the assignment. She initially said yes, but soon after countered with an alternative pitch: What if instead of her, we got James McMurtry to talk to Clark? The idea came up over dinner (and presumably, lots of wine) with friends, with McMurtry in attendance and apparently game if we were.

It was an offer too intriguing to refuse — and not just because McMurtry contributed one of the Clark tribute album’s most lauded cuts with his cover of “Cold Dog Soup.” You see, in addition to his acclaim as a songwriter’s songwriter himself, McMurtry also happens to be one of Texas and Americana music’s most notoriously, shall we say, “challenging” interview subjects; so, naturally, I thought it’d be fun to watch him tackle the Q&A experience from the “Q” side of the fence. And so, with help from Saviano and Austin-based radio promoter (and McMurtry handler) Jenni Finlay, we set McMurtry up with an advance of My Favorite Picture of You, Clark’s phone number in Nashville, a digital recorder and a bottle of red wine, and sat back to see what happens when one of Texas’ greatest living songwriters interviews well, THE greatest living Texas songwriter. — RICHARD SKANSE]

***

I first heard Guy Clark’s Old No. 1 album in a chilly, breezy apartment in San Francisco around 1982. I was visiting a friend from the Panhandle who lived in the North Beach district in an old brick building that had survived the 1906 earthquake — an unsettling fact, due to the city engineers’ assertions that the ’06 quake had caused enough structural damage that the building probably wouldn’t survive the next big earthquake. There seemed to be no way to get warm. The clammy Bay chill snaked its way through multiple layers of flannel like a yellow cab down a back alley at rush hour, no stopping it, no sir. Hot coffee and cigarettes only confused the chill for a minute, as if causing it to drive around in circles looking for the address before settling in again, right down to bone-marrow depth.

My friend had a good stereo with a belt-drive turntable, and a row of LPs along one baseboard.

“Ever heard Guy Clark?” he asked. I hadn’t. I looked at the cover, recognizing the title “L.A. Freeway” from a live Jerry Jeff Walker record that I’d worn out as a teenager. “So this guy wrote that.” I don’t remember how far into the record I listened before I forgot I was cold, but I did forget. I was transported to warmer climes like Monahans, Texas in 1947, a place and time I never knew, but now thought I could see vividly, or a hot, gritty Dallas sidewalk in the company of a wine-soaked elevator man. Guy’s voice will take you somewhere else every time you hear it.

About 1986, I remember racing my pickup out IH-10 from San Antonio to Kerrville because I’d found out belatedly that Guy was hosting a “Ballad Tree” at the Kerrville Folk Festival. I made it just in time and played an early, bridgeless version of a song that would eventually become “Talking at the Texaco,” probably way too fast, stage fright being my life in those days. I don’t remember if Guy had anything to say about my song, but I remember that he had an awfully gracious manner for a man who’d been forced to stand under a tree in Kerr County on a hot afternoon listening to a bunch of us young’uns try to impress him with our songs.

In all my later encounters with Guy Clark, he always displayed that gracious manner, never condescending or full of himself in any way, what we call “no bullshit.”

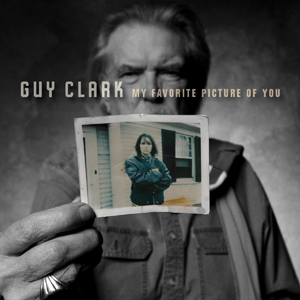

Guy’s new record, My Favorite Picture of You, is a stellar work: well written, well performed, well produced, and greater than the sum of those parts, as a good record must be. I am now much older than Guy was when he posed for the picture that graces the cover of Old No. 1, and I’m probably guilty of no longer being as curious as I ought to be. I rarely listen to a disc all the way through, or a song for that matter. Usually, I skip to the next track at the first whiff of boredom. I found no whiffs of boredom on this record. I even tried, on second or third listening, to pick the record apart, trying to channel the jaded ears of producers and engineers I’ve worked with, to find some fault that would guarantee my continued status as a full-blooded cynic, but I really could find none. My Favorite Picture of You is simply another great Guy Clark record. That’s all.

Guy’s new record, My Favorite Picture of You, is a stellar work: well written, well performed, well produced, and greater than the sum of those parts, as a good record must be. I am now much older than Guy was when he posed for the picture that graces the cover of Old No. 1, and I’m probably guilty of no longer being as curious as I ought to be. I rarely listen to a disc all the way through, or a song for that matter. Usually, I skip to the next track at the first whiff of boredom. I found no whiffs of boredom on this record. I even tried, on second or third listening, to pick the record apart, trying to channel the jaded ears of producers and engineers I’ve worked with, to find some fault that would guarantee my continued status as a full-blooded cynic, but I really could find none. My Favorite Picture of You is simply another great Guy Clark record. That’s all.

Cell phone rings in Austin. Display shows a 615 area code, Nashville and vicinity …

***

Hey Guy, how you doin’?

Pretty good, how are you? Sorry I couldn’t get to the phone right when you called the first time, but here I am now.

Here you are …

Are you coming over?

No, I’m in Austin.

Oh, you’re in Austin. So it’s gonna be a phone interview. Man, I was hoping you were coming here today!

I wish I was, too. But they’ve got me wired up to some kind of hard drive that records so they can transcribe it. We’ll see how it works — I’ve never conducted an interview in my life.

[Laughs] Well, I’ve never done one, neither. But I’m sure we’ll figure it out.

I guess we’ll start with the usual dumb journalist thing and cover your background. You were born in Monahans or somewhere out there, right?

Yeah, Monahans.

And then you moved to Rockport?

Well, yes and no. From third to fifth grade I moved to Houston, when my dad was in law school at the University of Houston.

I attended the first grade in Houston, then I got out of there. So you spent third, fourth, and fifth grade there, and then you moved to Rockport?

Yeah. From sixth grade through high school.

And then I guess you were in Los Angeles for a while, and finally Nashville for the duration?

Yeah. Well, I lived in Houston in the ’60s mostly, then spent about a year in San Francisco in ’69.

That must have been an interesting time to be there.

Yeah, it was pretty crazy. And then I moved back to Houston for a little while, then I moved back to L.A. I had decided to try to get in the music business by that time. So I moved there, worked in a dobro factory for about a year, building dobros trying to make a living. And I got a publishing deal out there. I would just go around with my guitar, singing for people, because I didn’t have any tapes …

You’d just go in people’s offices and sing them your songs?

Yeah. Anybody I could get to sit and listen. So I got a publishing deal with RCA’s publishing company, and they said, “Where do you want to live?” And I said,

“Anywhere but L.A.!” [Laughs] So anyway, I came to Nashville, because L.A. just didn’t suit me. It still doesn’t.

Is that the experience that “L.A. Freeway” came from?

Yeah, exactly.

You used to tell a story about that song, about some kind of tree at the place you were living at that cracked the owner’s driveway …

Oh yeah. It was a garage apartment behind a house, and there was a grapefruit tree out there, which was really cool. And one morning I woke up to the sound of this landlord out there cutting down that tree, because the roots were messing up his driveway. And I just thought, “Oh man … suspicions confirmed!” So anyway, after that we packed up the old Volkswagen Bus and took off; we moved to Nashville, and I started doing what I do. The only person I knew here at the time was Mickey Newbury, who was from Houston — he and Townes [Van Zandt] were friends.

Didn’t you end up going back to Los Angeles somewhat later to make the album that “Heartbroke” was on? I remember a story you told once about cutting that song in L.A. with Ricky Skaggs.

Right. We couldn’t find anybody to play fiddle like we wanted in L.A., so we brought Ricky out there to play on it, and he said, “Ah man, if I ever get a record deal, I’m gonna do that song.” “Hearbroke.” So he did.

Didn’t he change some words on it, though?

Oh, yeah — he didn’t want to say “bitch.” He said, “I’m sorry, I had to change some lyrics, I couldn’t stand for Mama and Daddy to hear me sing that word on the radio.” [Chuckles] I said, “You do what you need to do, Ricky, I don’t care.”

Let’s talk about some of your newer songs. This record here, My Favorite Picture of You, is amazing.

Oh good, you heard it?

Yeah I did. It’s a jewel. But I don’t have any artwork for the record yet — I just have a printout with the songs listed on it, and one of them was misnamed. You’ve got one on here called “Hellbent on a Heartache,” and my printout says “Hellbent on a Headache.” I could kind of imagine you doing that, though — I do that now and then!

[Laughs] That’s pretty good. That might have to be another one! But yeah, I’ve just seen the artwork myself in the last couple of days. I think it came out pretty good. They’re actually pressing up vinyl albums for this one.

That’s great. I like that vinyl’s come back.

It’s kind of nice, yeah. I hadn’t had a turntable set up in so long, and I’d gotten rid of most of my LPs. I’ve got a few left, but I probably threw away about 100 because they were so scratched up and fucked up, they really weren’t worth keeping.

Another one of the songs here is “The Death of Sis Draper.” I remember your first “Sis Draper” song [from 1999’s Cold Dog Soup] — how many other installments do you have now?

Well, Shawn and I co-wrote the first one, and then we kept thinking, “Man, there’s another song in here somewhere.” So we started thinking up other situations that would fall into that, and there’s probably seven or eight songs that reference Sis Draper at this point. I can’t bring all the others to mind at the moment, but this one’s about the death of Sis Draper, because we couldn’t think of anything else and finally went, “We need to killer her off!” We just made it up where she got poisoned by a jealous barmaid, which seemed appropriate. But Sis Draper was actually a real person; she was the woman who taught Shawn to play fiddle when he was a kid, so it’s kind of loosely based on truth.

Wow. I was wondering where that character came from. In the first one, you used “Arkansas Traveller” as sort of a canvas to put it on, and this last one goes to “Shady Grove,” it sounds like.

Yeah, that was the other thing we were doing, is using traditional bluegrass tunes for all of these songs. We also did that with “Soldier’s Joy,” which was recorded [for 2002’s The Dark] as “Soldier’s Joy, 1864.”

I’m curious about “Cornmeal Waltz.” You really capture that Texas dancehall culture, which I saw very little of. I never saw anybody put cornmeal on a dance floor …

Yeah, I had not, either. I had never heard of that. And Shawn Camp, we were just talking one day, and he was talking about playing dances at some of those dancehalls, and how they’d throw a handful of cornmeal on the floor, and I just started laughing, because I had never heard of that, but I knew immediately what it was when I heard it; I mean, it couldn’t be anything else. So we were like, “Well, there’s a song — ‘Cornmeal Waltz!’” And we just wrote it that day.

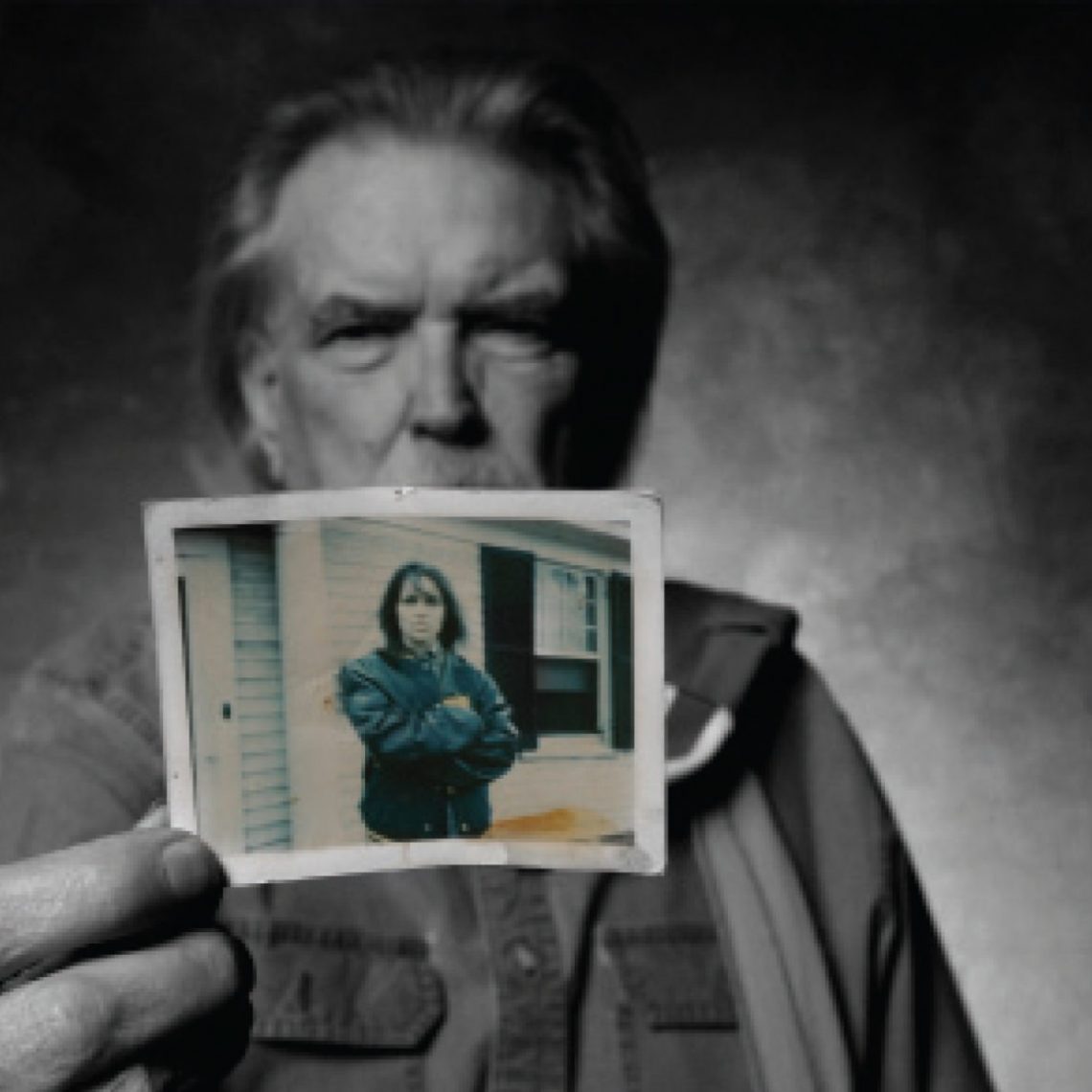

Some of these songs, you’re digging pretty deep. Like the title track, “My Favorite Picture of You.”

Yeah, that’s a real true one. I’ve had that picture of Susanna [Clark’s wife, who passed away last June] since the day it was taken, which was probably in the late ’70s, early ’80s. Townes and I were at John Lomax’s house in Nashville, just drinking, being assholes, and Susanna had finally had enough, so she put on that old jacket — because it was cold and blustery — and walked outside. And I guess it was Lomax who snapped that picture — I don’t really know who snapped it, but for some reason, that photograph always captured my imagination of Susanna. Like, that’s her — that’s what she looks like, to a fault. I don’t know, it’s just always been my favorite picture of her, and I have it pinned on my wall. And this guy [Gordy Sampson] came over to write with me, and he had this laundry list of hooks and titles, and I came across that line “my favorite picture of you,” and I just went, “Man, I have that picture. As a matter of fact, it’s right there.” And we just took off from there.

That’s a pretty brave song to write. I’ve never really been able to dig into my own experiences that way. I always have to fictionalize a lot, try to keep my distance from it. Does that get easier as you get older?

No. [Laughs]

I didn’t think so.

No, it doesn’t get easier. But sometimes it presents itself, so you don’t really have to work as hard at it. Like that song, I knew it could be good, and I knew what it was about, so all I had to do was grab that picture.

“Heroes” is another brave song. You went after the war this time.

Yeah. That came about when the guys I was writing with that day, we all related this story at the same time, because we all had just heard it on TV or read it in the paper or something. But it was about how there are more suicides by guys coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan and all that shit than there ever have been in the history of American warfare. The Civil War, Vietnam, nothing — not even close to the suicide rate of these guys coming back today.

Well, that sure needs to be written about. They seem to keep this war so invisible to the rest of us. Even the first Gulf War had more coverage than this. This one just kind of goes along, and we go about our normal lives and just don’t look at it anymore. We get numb to it, and that’s the scary party.

Yeah. I thought that needed to be addressed. And I felt the same way about that song “El Coyote,” about those coyote smugglers that bring the illegal aliens over to work, and how brutal they have to be to do that. There was the story, I’m sure you heard about it, where 18 braceros got locked in the back of a semi truck parked out on the side of the fucking highway in South Texas, and they all died. They couldn’t make enough noise to get somebody to get them out. This guy who had been transporting them, something spooked him — like he thought he was going to get caught, so he just parked the truck and left them there and walked off.

He didn’t even bother to throw open the back of the trailer.

No, he did not. And they all died. And there was another story about this guy in Mexico who would guarantee that he could get you across the border with no trouble for $1,100 bucks a piece. So he’d get his truck loaded with, I don’t know, 20 or 30 guys, and he’d get them across the border all right, but then he would immediately turn them in to the border patrol — for $1,100 a piece.

So he was getting it on both ends. Wow. I don’t go near that border anymore.

Yeah, it’s getting dangerous. I haven’t been down there in a long time.

What’s the title of this second to last cut on the record? Is that “Inspiration”?

“The High Price of Inspiration.” Yeah, that’s a neat song. I wrote that with a young Australian guy named Jed Hughes. He’s a wonderful guitar player. Anyway, we’ve become friends, and he came over, and I think I had that line written down on a page somewhere from several years ago, “the high price of inspiration,” and we just started from there, building it out.

And so, the high price of inspiration being … insanity?

Oh yeah.

Insanity and chemicals, I guess … I’m sitting here at high noon drinking Malbec, a red wine from somewhere south of here.

[Chuckles] Good for you. I wish I still drank. I quit drinking five, six, seven years ago. I had lymphoma, so I had about four months of chemotherapy, and I couldn’t wait to get through with that so I could sit down and have a nice glass of wine or whatever, tequila. But then I tried it, and it tasted like shit! I had to spit it out. I lost my taste for alcohol. I still keep a bottle of tequila around here and once in a while I’ll have one shot, but that’s it. I don’t want anymore. I don’t like the taste of it anymore. And I was so disappointed!

You could probably push through that and learn to drink again, but it doesn’t sound like you’d want to or need to.

Yeah, I don’t know. Sometimes I miss it. But I just don’t want it bad enough to go get it.

Well, that’s probably a good thing. It took me several attempts to quit smoking, and I haven’t had a cigarette in 17 years I think, but I remember there were a couple of times before where I was actually off them long enough that I couldn’t smoke and had to learn again — I had to get past that cough to get that great first hit. I don’t know why I was stupid enough to push past it, though; I guess I was just young, you know.

Oh, I still smoke. But I use rolling tobacco.

Yeah, that’s what I did. When I quit, I was rolling Drum, and it was much easier to quit off of the Drum than it was R.J. Reynolds product, because there’s not so many additives. I was only crazy for about two months.

I’ve been rolling my own tobacco all my life. When I was in grade school, one of my jobs around the house was to get up in the morning and roll two packs of cigarettes for my dad before school. So I’ve been doing it since the third grade. And I mean, I’ve tried to smoke other kinds of cigarettes, but I always wind up going back to rolling my own tobacco — in part because it doesn’t have all those extra chemicals like saltpeter in it to keep it burning like a fuse. So I still smoke probably five or six cigarettes a day.

I remember all that; I miss it. I actually had a dream last night that I lit a cigarette … and it was great! I woke up all relaxed. But I still can’t do it. I had to quit because I kept getting bronchitis, and I had to go on the road and I kept getting sick, and I just wanted to get well. I figured, you can work or you can smoke, what you going to do?

Yeah. It’s hard to find a smoking motel now.

It is. And you know, I was against all the smoking bans, even long after I quit, because I thought it would hurt the bar business, which would hurt my business, but it didn’t really. And now we really notice that if we play in North Carolina or somewhere where they still smoke in the bars, you open up the van the next day and it’s like opening up an ashtray, because the smoke sticks to all the cases and everything.

[Laughs] Yeah.

Oh, another thing I wanted to ask you about was this song called “Good Advice.” That’s a type of song that I start into every once in a while, and I just can’t get very far. You’ve got a combination of lines there that by themselves would be cliché, but the way you put them together, they’re not. That’s a good trick, I gotta say. I’ve never been able to pull that off.

Yeah. I’ve thought several times about that song and about whether that song was right or not. And you’re exactly right, it’s different clichés going together … But I almost didn’t put it on the record. It was a toss up.

I think you made it work.

Well, good. I appreciate your input!

Now, “Waltzing Fool” is one you covered, right? Didn’t Lyle Lovett write that, or did you?

No, “The Waltzing Fool” is one Lyle wrote. It was on his very first record and just always stuck in the back of my mind. And one night Lyle called me and asked me to come down and sing a song of his for this awards ceremony for ASCAP that he was doing. I said sure, I’d do it, and learned that song to play at this ASCAP show. And then the next morning we went in the studio and recorded it. I said, “Let’s do ‘The Waltzing Fool’ — I just did it last night.” There’s just something about that song that touches me.

I remember seeing you and Lyle play one time at the Vick Theater in Chicago. It was you and Lyle and John Hiatt and Joe Ely, and it seems like John Prine was there, too …

He might have been there in Chicago, yeah. It was me and Joe and John [Hiatt] and Lyle, but we were sometimes joined by friends at those things.

I was there with some bone-headed Columbia Records local rep, and he pointed to the stage and said, “You know these guys?” And I said, “Well, I can name them all.” He thought we were all a bunch of hicks.

[Laughs] Yeah, it was fun doing those shows, but I don’t think I’d like a steady diet of that, because travelling with those guys … well, Lyle and Joe, they like to play just every night. I mean, bang-bang-bang-bang-bang. I like playing and then taking a day off to get to the next gig, playing every other day maybe, because usually its just me and Verlon Thompson driving. But they’re into that bus thing, and if you’re paying for the bus already, you might as well drive to Poughkeepsie, N.Y. from Colorado overnight, that kind of shit. I don’t like that.

That was the first of those songwriter-in-the-round shows I ever saw …

Yeah, but we did it before that. I remember how it started … Marlboro, when they could still advertise, started supporting that tour. I can’t remember exactly how it went, but I think we had just done it as a one-off here in Nashville, and I guess it seemed so successful that the Marlboro people wanted to use us as their shills, you know. So they took us and talked about how, you know, “this is how you discuss cigarettes with the media, because you’re going to get interviewed, and they’re going to bring up, you know, ‘what about all this hoopla about smoking and stuff?’ …” They taught me how to dodge questions in an interview; like, it was real slick, how to get around whatever it was that they were asking you that you didn’t want to say. I mean, it was an interesting experience. [Chuckles]

Well I guess you were able to put that training to use in later interviews … such as this one, perhaps.

Yeah, right! Well, if you feel like I’m steering you in another direction, it’s just because it’s the only way I can do these things.

I don’t care, I just need to know some of those tricks myself, in case somebody wants to talk to me! I’m always looking for ways around telling the truth.

[Laughs] Yeah.

I remember, it seems like Hiatt stole that particular show I saw with a song called “Since His Penis Got Between Us.”

Say what?

He had a song called, “Since His Penis Got Between Us.” Remember that one?

[Laughs] No, I can’t remember it. Huh. But yeah, John writes some good songs. And he’s such a great guitar player. His rhythms and his singing are really complimentary.

We were on a cruise ship together last year, that Cayamo Cruise. But they didn’t ask me back this year. I was on the boat a whole week, so I was probably an asshole to somebody somewhere along the way.

Well of course! That’s how you do it — that’s why they had you!

It was a pretty good time, though.

Well, good. You know I’ve never done one of those. I guess I’ve been asked, but I’ve always said no, because I just had this feeling in the back in my head that there would be this pervading white noise from the engines.

No, they’re actually pretty quiet. And we got lucky, the seas weren’t too rough. I saw some whales off the bow one day, which was really cool. I don’t know if I’ll be doing it again, though. The problem is, there’s just nowhere to hide …

[Laughs] Right.

Anyway … I’m rambling now. But I think I’ve probably got enough stuff here to put something together, maybe.

Are you saying you want to quit, or what?

No, I’m saying the wine is taking over, Guy!

Oh it has? [Laughs]

Yeah. I might have to take off while I can still drive, so I can get home. But it’s been great talking to you. I’ll try to cut this up and make it look like it makes some kind of sense.

Well, thanks for calling. I appreciate it. James, it’s been good fun … [Connection quality falters.]

You cut out there for second, Guy. What were you saying?

I’m talking about the interview, talking to you! Good fun. Stay in touch.

I sure will. And if I get to Nashville, I’ll give you a call. I think my son’s planning on moving up there in August. He’s a much better songwriter than I am. He can write pretty much anything.

Hah! Well, have him call me if he wants.

Really enjoyed this impromptu interview. The pros aren’t always the best interviewers…