By William Michael Smith

(LSM March/April 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 2)

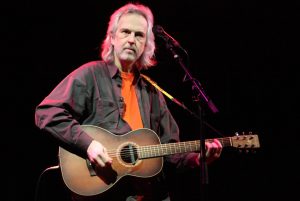

Austin producer, picker and songwriter Gurf Morlix has been waiting 20 years to record a tribute album to his late friend, Blaze Foley, and he finally got around to Blaze Foley’s 113th Wet Dream in late 2010. The 15-track album, a wonderful cross-section of Foley’s small but impressive publishing catalog, hit stores in February. Morlix’s choice of material is impeccable and he absolutely nails the essence of Foley’s work with his interpretations.

Outside folk and roots rock circles, Morlix is not exactly a household name. Yet inside the Americana musical world, he is almost universally acknowledged as a gentle giant. Probably best known as a producer, he rests on the same pedestal as people like T Bone Burnett and R.S. Field, prolific producers with important bodies of work that don’t necessarily follow the obvious commercial path but who conjure choice records that get noticed. Known for his no-nonsense, bare-bones approach, Morlix broke into record production with Lucinda Williams’ acclaimed breakthrough albums Lucinda Williams (1988) and Sweet Old World (1992), and has since produced albums by an all-star list of Americana acts: Robert Earl Keen, Slaid Cleaves, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Tom Russell, Hot Club of Cowtown, Butch Hancock, Mary Gauthier and BettySoo.

Morlix’s traumatic split with longtime musical partner Williams may mark the most public part of this relatively private man’s life. With 90-percent of Williams’ album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road finished, Williams decided to scrap the project and start over in Nashville. Shortly after the sessions began, Morlix and Williams butted heads and he decided to quit the project, ending a highly successful 11-year association with Williams as her band leader and guitarist. Redone in Nashville with Steve Earle, Ray Kennedy and Roy Bittan, the album went on to receive a Grammy and was voted the top record of 1998 in the Village Voice Pazz and Jop poll.

As a player, Morlix has been an in-demand sideman since he first moved south to Austin to escape the icy winds of his native Buffalo, N.Y. Not long after arriving in Austin in 1975, Morlix teamed with legendary Dallas folk-rocker B.W. Stephenson. Subsequently, along with his new musical partner Foley, Morlix became a fixture on the burgeoning Houston folk scene in the late 1970s, before parting with an increasingly off-the-rails Foley and leaving for Los Angeles in search of a wider pool of musicians. It wasn’t long before a fateful phone call had him working with Williams, who was just finding her true stride after years of dabbling in bluegrass and folk music. Since his split with Williams, Morlix has gone on to play with respected Austin acts like Hubbard and Cleaves. Along the way he’s worked with a list of people that reads like Who’s Who of roots music: Warren Zevon, Buddy and Julie Miller, Robert Plant, Patty Griffin, Jim Lauderdale, Ian McLagan, Troy Campbell, Jimmy LaFave and Eliza Gilkyson. Morlix also worked on four tracks for the movie Great Balls of Fire with Jerry Lee Lewis. He was named the Americana Music Association’s Instrumentalist of the Year in 2009.

The consummate sideman, Morlix eventually found the impetus to record an album of his own material. His 2000 debut, Toad of Titicaca, served notice that there was a major new talent on the Austin scene. He has since released six more albums to broad critical acclaim; each record has been something of a concept, from the dark rock ’n’ roll of Fishing In the Muddy (2002) to the neo-country Cut ’N’ Shoot (2004). But it was 2007’s dark, spiritual Diamonds to Dust that seemed to suddenly vault Morlix’s work up a notch. Last Exit to Happyland (2009), an exploration of mortality and life-meaning, produced some of the most beautiful work of his career. Austin songbird Patty Griffin added vocals to several of the most memorable tracks.

In fact, Griffin is part of very small team that Morlix has assembled who seem absolutely committed to his art and vision. Morlix seldom records with anyone but Rick Richards on drums, and while he has worked with Ruthie Foster, BettySoo and a few other women, Griffin remains his go-to voice for harmonies. The loyalty of Griffin and Richards are simply further testimony to Morlix’s integrity.

We caught up with Morlix at his Rootball Studio just outside Austin as he prepared to play the first shows of what will be a year-long tour paired with Kevin Tripett’s documentary, Blaze Foley: Duct Tape Messiah.

When did you get your start in music?

I knew very early on that I wanted to play music, really ever since I heard the Everly Brothers on the radio when I was in elementary school. And then I was in that generation that got to see the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, and that event altered my life just like it did so many others.

So how did you get into being a professional musician?

I learned bass and was actually playing in bands by the time I was in high school. It was one of those times when everybody wanted to be in a band, that was the coolest thing. The thing I find really funny now is that I made as much at some of those early gigs when I was in high school as I do now.

Your parents were supportive?

Yeah, they were. We had our talks about learning a trade to fall back on, that kind of stuff, but I just kept telling them I wasn’t going to need that fall back. But they were great. I can remember my father taking me to gigs at biker bars and dropping me off, then coming back to pick me up. I’m sure it took a lot for him to lay back and let me do my thing, but he did.

What’s on memory from that high-school band period that stands out?

Peter Case also grew up in Buffalo, and I remember him coming to some of my gigs. So we found out he was also a musician and we let him get up and do some songs between our sets one night. He got up there and pounded out some old blues stuff on piano and sang. That was the first time he was ever onstage.

Wow, that is quite a mile-marker.

Funny thing is that we reconnected out in California much later in the ’80s. I was playing steel guitar then and he asked me to join the Plimsouls. Peter was just getting into exploring his folkier side at that juncture and he felt like a steel guitar sound would be cool. So I ended up playing with them during the final few months of their existence before he went solo.

What was the impetus to leave Buffalo?

I was tired of the cold [laughs]. I just decided I wanted to try someplace warm. I tried Key West for a while, but Austin seemed to be the happening place, so I moved here for the first time in 1975 and landed right in the middle of the Cosmic Cowboy thing.

You landed a great gig with B.W. Stephenson, who was very big at that time. What caused you to take that route rather than, say, join a rock ’n’ roll band?

I’m drawn to lyrics and songs. Austin was just brimming with great songwriters during that period. Even today, I’m much more into singer-songwriters than I am guitar pyrotechnics and whatnot. When someone asks me to produce an album, my main criteria is whether I connect with the songs.

How did you get connected with Blaze Foley?

I saw him sing a few songs one night and thought, “This guy is just completely different.” So I introduced myself and we started hanging out and eventually working together.

What led you two to move to Houston in 1978?

Money. Houston just had this great, bustling singer-songwriter scene with a dozen or so clubs with live music. And there were these great writers like Shake Russell and Dana Cooper, Danny Everitt, Michael Marcoulier, John Vandiver, Lucinda. It was just so much more lucrative financially than Austin. Blaze and I rented a place in Montrose right in the center of the action for $50 a month. Three or four gigs and we not only had our month made, we could eat out all the time. And that scene was so hot, it wasn’t unusual for us to play 20-25 gigs a month. And lots of nights we’d play gigs at two different venues. It was the busiest I’d ever been, and it was the most money I’d ever made. Plus it was just a cool scene to be part of.

What happened to that?

Things changed. Some of the oil money dried up. But for me it was Blaze. His drinking got real bad and he’d go off to Austin and then phone me to say he couldn’t make it back for a gig, stuff like that. So I finally told him I was moving to Los Angeles. When I moved out, he moved back to Austin.

You hooked up with Lucinda Williams not long after moving to L.A., and Lucinda Williams was the first album you ever produced. How did that come about?

We had a great band and were getting a lot of attention out there. Then out of the blue, Lu calls up and says she’s got a record deal, but who’s she going to get to produce it? And I said, “Me.”

What were your credentials to take on something like that?

My whole career I’ve always been the guy with the tape recorder. I was always the guy who’d get things to sound right. I think I knew what a good record was supposed to sound like. Anyway, that’s how it came about and it turned out okay, I guess.

You’re very much in demand as a producer these days. How do you decide which projects to take on?

It’s really all about connecting with the songs. I probably pass on 75-percent of the offers I get, and that’s usually just because I don’t personally connect with it.

How did you get into having your own home studio?

When I moved back to Austin in 1991, things were really changing. Equipment was getting more affordable, and the business was changing. Before that you needed a record label behind you to get into a studio and do a record. But suddenly it was getting where anyone could do one. My buddy said we should build a studio and just record all the time.

It seems like you use Rick Richards exclusively as your drummer, not only on your records but on the other albums you produce, too.

I met Rick way back in the day and thought he was just okay. But we reconnected when I got back to Austin and I was just blown away by how accomplished he’d become.

So what makes you guys click?

His pocket is so tight. If I had to play drums, his pocket is exactly the one I’d want to lay down myself.

Ray Wylie Hubbard is always singing your praises, and you’ve produced four albums for him. How did that collaboration come about?

I’d actually met Ray back in the ’70s in Austin and thought he was very talented, very funny. He had this kind of charming persona. Then I lost track of him for quite a while. Anyway, we reconnected in the ’90s and he came out to look at my studio. He asked me what I was listening to right then and I said I was really into prison chain-gang stuff. And he said he had been listening to field hollers, so we just sort of instinctively knew that we were on the same wavelength. And once I heard some of his songs, I thought, “He’s as good as anyone at this,” so I wanted to work with him.

Slaid Cleaves had bounced around for a little bit, too, but it all seemed to come together for him after you started working with him.

The first thing I loved about Slaid was that voice. He’s no opera singer, but he really puts his songs across, and that was the first attraction for me. We did No Angel Knows in ’97 and it didn’t do all that well and Slaid started to get a little discouraged. But when we were finished with Broke Down [2000], I told him, “Your life is about to change, this record is going to grab some people.” And he was like, “You really think so?’”

You finally put out your own first record, Toad of Titicaca, that same year. Why did you wait so long to begin to do your own thing?

Having my own studio is what really made that possible. I’d been writing songs for maybe 30 years, but I was just never sure they measured up. That’s a funny thing; I can usually tell right off about someone else’s songs, but I go back and forth about my own.

So why did you decide to do the Blaze Foley record at this juncture in your career?

I’ve been in touch with Kevin Triplett about the documentary for some years and have watched that develop. With him finally deciding to take the film public, it just seemed like the time was ripe to put out the Blaze record.

What are you doing next?

I’ve got quite a few songs for the next record, but I probably won’t start working on that until sometime next year. For the rest of this year, I’m going to play as many gigs as I can, and we’re trying to coordinate as many of those gigs as possible with showings of the film.

No Comment