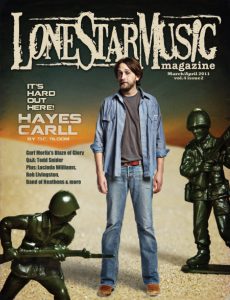

By D.C. Bloom

(LSM March/April 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 2)

Hayes Carll opens the door and immediately apologizes for the two rambunctious dogs of uncertain breeding that are barely containing themselves at his feet. With an assuring, “They’ll settle down in about 10 minutes and then forget about you,” he invites his guest inside his northwest Austin home, which exudes a comfortable, lived-in, Southwest American vibe, and drops his tall, lanky frame onto a leather sectional. Then, suddenly remembering his Texas manners, he jumps back up, asking, “Water?”

When Carll goes into the kitchen for the proffered beverage, the dogs take full advantage of his brief absence to engage in even more frenzied guest- and furniture-jumping horseplay. The chaos subsides when their master returns, but straight away he notices something has gone amiss. One of the dogs has scratched what apparently had been a pristine, perhaps brand new, leather ottoman.

“Oh, boy, now you’re going to get it,” he scolds the offending mutts. “You see what you did?” From the look of concern on his face, it seems Carll fears he’ll be in for a stern reprimand of his own later that afternoon. For the next 10 minutes or so, he occasionally leans forward and eyeballs the damage, shaking his head sadly. Only when both dogs have dozed off does his body and manner finally start to relax.

The Hayes Carll that you see when the award-winning Texas songwriter steps onstage for a concert is the exact same Carll you get in the living room of the house he shares with his college sweetheart wife and their young son: disheveled, plaid-clad, somewhat sleepy-eyed and quick with a quip. But the domesticated Carll is also not unlike any other thirtysomething husband and father you might find in a typical suburban neighborhood of young families at the early stages of their careers. They’ve survived the wild and crazy years of their 20s, when the roads seemed to go on forever and parties never ended until the dawn’s early light. And they’re now settling into hearth and home, relishing the ripening fruits of careers beginning to gel after putting in the countless hours and sweat equity it takes to climb professional ladders anywhere, whether you’re a school teacher, corporate accountant, or even — so you’ve been told — the next Townes Van Zandt.

None of this happens overnight. But as the focus of conversation shifts from blemished living-room leather to his budding career and rising name recognition, Carll can still recall, as if it were just yesterday, a time more than a decade ago when the waves of fortune didn’t seem to be breaking his way at all — especially not as they all seem to be breaking for him now, what with a Tonight Show appearance just a few days away in advance of his second major-label album, KMAG YOYO (& Other American Stories).

Every working musician remembers the first time that they stood in front of an audience that had actually paid good money to watch and listen. It can be a defining pivot point between merely busking for tips and gas money, and, maybe, just maybe, being able to quit the proverbial day job. For Carll, that fateful gig came when he’d been asked to open for the popular regional Texas duo, Shake Russell and Dana Cooper. There were actually three acts on the bill, with Carll sandwiched in the middle.

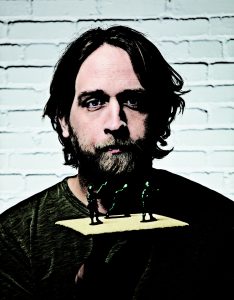

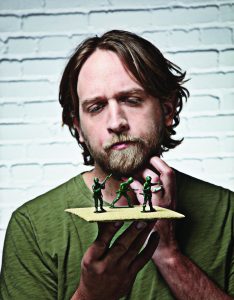

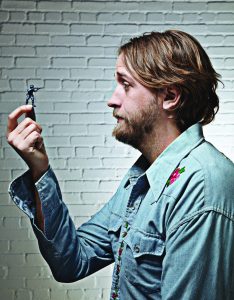

“The guy that opened for me was this comic who somehow incorporated water balloons and kids’ action figures into his act,” Carll recalls. “So I’m about halfway into my first song, nervous as hell, and I break a string. I look down and realize I’m standing there in a puddle of water and G.I. Joe body parts. And I’m thinking, ‘Damn, the whole thing just went to shit.’”

Or, perhaps that was the taunting voice of fate, whispering in his ear: “Kiss my ass, guy, you’re on your own.”

***

Basic Training

There’s really no field manual outlining the how-to’s of becoming a successful singer-songwriter in the good old U.S. of Americana. The Hayes Carl way has relied on equal parts son-of-attorneys ambition, some slacker-dude serendipity, and an all-around good guy’s charm and guile. Combine these with a flair for dramatic expression and a drunken poet’s way with words, and, well, you just might have something.

Specifically, what you’d have is a long, tall character named Joshua Hayes Carll who played hoops through high school in The Woodlands, Houston’s upper middle class suburban planned community with The Pretentious name. But it wasn’t just sports occupying the lad’s time. He was also a bit of a theater geek. “Theater was a good outlet,” Carll says. “I was really into it because it was a chance to hang out with people who were reading books, or writing poetry, or playing guitar, or doing drugs, or just expressing themselves in whatever way. It was a whole mix of people and it was a lot of fun socially for me.”

Naturally, he figured pursuing a theater degree at Hendrix College in Conway, Ark., would offer a similar experience to the one he enjoyed in high school — but that turned out not to be the case. So he shrugged out of his theater major and shifted gears to history. “It was what I had an aptitude for, and I liked the stories associated with it,” he explains simply.

For the most part, though, Carll spent his Conway years bemoaning two facts: he’d picked a school in a dry county, and he lacked a car that could get him down to Little Rock, were there were bars a plenty and even potential gigs for a fledgling songwriter, as he’d already begun to fancy himself. But opportunity just wasn’t beating down his door, and he didn’t quite have the ambition to go chase it down yet, either. Meanwhile, adding to his angst was the attractive co-ed he’d taken a fancy to — the future Mrs. Hayes Carll. She had a working band that, unlike Carll, was actually landing a fair amount of bookings in the area. “It was an all-girl band, and they all wore leather pants,” Carll explains with a grin. “It was tough to compete with that.

“The whole time I was there, I was very restless just to get out and hit the road,” he continues. “I was thinking, ‘Okay, Bob Dylan signed his publishing deal at 19 and put out Freewheelin’ at 21, and I’m 21 sitting in history class, hungover in Conway, Arkansas.”

While the frustration Carll felt was no doubt real, the reality is that Robert Zimmerman so wanted to become Bob Dylan, he didn’t idle his hours away just thinking about it. Rather than nursing endless headaches, he got his Minnesota ass to New York City and started auditioning for John Hammond. By contrast, Carll’s notion of becoming a working singer-songwriter was less of a self-motivating obsession than an idle fantasy — like an incoming freshman who says he’s pre-med but really isn’t all that keen on studying chemistry and biology for hours on end. By Carll’s own admission, “I really wasn’t ready to give it a go yet.”

***

Under the Radar

Carll earned his degree in history at Hendrix College (“by the skin of my teeth”) and did what any newly minted but unfocused college graduate would do: he headed to the beach. More specifically, to Crystal Beach on Texas’ Bolivar Penisula, where his parents, rather conveniently, had a beach house that would serve as Carll’s home port for a year or so.

“There are a lot of good people down there, but everybody was kind of laying low and living under the radar,” he recalls. It would be the perfect proving grounds for Carll as he honed both his songwriting craft and his performing act. He became a popular fixture at the dive bars and restaurants of the area (check out the animated Youtube video, “Hayes Carll: Crystal Beach Memories,” to get a good feel for the colorful folks who were his earliest fans and the not-so-glamorous places he’d play).

When he wasn’t playing the seedy saloons and one-star restaurants on Bolivar, Carll waited tables and tended bar in Galveston, a short ferry ride across the bay. One night after work he went out with some co-workers and, as he tells it, “just happened to walk by the Old Quarter, totally by happenstance. I heard a guitar playing from inside and I made everyone come in with me.” He had stumbled upon Rex “Wrecks” Bell’s intimate establishment of Townes’ Live at the Old Quarter fame. Carll took to this holy ground like a snapper to saltwater.

“There was a cute girl behind the bar and pictures of my heroes on the wall and an open-mic night — I knew this was were I was gonna hang out,” Carll says. “So, whenever I had a night off playing covers for drunks and sailors on Bolivar and trying not to piss anyone off, I’d go over to the Old Quarter. It was my refuge … and I could play my own songs and meet other songwriters.”

Bell describes Carll’s Bolivar years like this: “He had one of those degrees where you either teach or go back to graduate school, and he was living at that beach house until he figured out which one it’d be.”

Carll would ultimately enroll in graduate school — graduate school in songwriting, that is, at Old Quarter U. The education there was unlike any he could have recieved at a place like Boston’s renowned Berklee School of Music. It was hands-on and real, and the passion he needed to become the songwriter he dreamed of being was fueled and flamed. “At the Old Quarter, you’re in a room where everyone is coming in and playing Townes Van Zandt songs, and it just kind of raises the bar,” Carll explains. “It really pushed me to focus on the lyrics and writing.”

As Carll’s trove of quality tunes grew, Bell started letting him play on Friday nights and also would suggest his name as a potential opener to people like Willis Alan Ramsey, Steve Fromholz, Sisters Morales and Ray Wylie Hubbard. Most of them figured Bell’s endorsement was good enough for them. Hubbard recalls “seeing this young guy at the bar playing the video gambling machine who then got up and played wonderful songs of such depth and weight. I really liked his stuff.”

But it was more than the material. By now, Carll’s confidence was brimming, and that had turned a once somewhat shy guy with a guitar into a charismatic troubadour who audiences wanted to root for. “I’ve compared him to Townes because Hayes is a stylist who writes from the heart and has an easy-going presence,” Bell says. “He was easy to listen to and easy to like … and had a real ease on stage.”

The Townes comparisons were meant as the highest of compliments and heightened Carll’s stature in the early years of his career, but they also were a bit of an embarrassment to the young songwriter. “I used to take down posters from record stores and bars that would have ‘The Next Townes Van Zandt,’” he says. “It was cringe-inducing for me. I was not Townes Van Zandt and never will be. It was like, ‘I’m not worthy!’”

***

No Retreat, No Surrender

Carll would eventually — like most Texans with guitars — make his way to Austin. But he found that being a big fish on the beaches of Galveston Bay made him just another guppy in the big pond of the Live Music Capital of the World. “I just got my ass kicked,” he says, “It just didn’t work at all for me.”

How bad was it? Foregoing a cheap apartment and just staying on a friend’s couch for the duration? Check. Working crappy day jobs? Let’s put it this way: Carll did more slinging of Red Lobsters to hungry Austinites then he did singing to adoring crowds at Saxon Pub. He also did a stint selling Hoovers door-to-door — poorly. “I wasn’t a good vacuum cleaner salesman,” he admits.

Further, he wasn’t really sure where his style of music could fit into the Texas music scene. “Bolivar was a remote place, and it wasn’t like people would come and say ‘You ought to check out Pat Green,’” he explains. “They were listening to Roger Miller and Lynyrd Skynyrd. And the Old Quarter was more focused on the heavy hitter songwriters. I knew about Jack Ingram from being from The Woodlands, but the rest of the burgeoning scene? I was oblivious to it.” It wasn’t until one Sunday, when the usual sparse crowd he played to at the now defunct Saengerhalle in New Braunfels was even more dead than usual, that Carll found out about a thing happening that day at Gruene Hall called the Americana Jam.

The raucous scene he discovered when he finally made his way there was “like this quintessential Texas music moment,” filled to the rafters with rowdy Texans of all ages being treated to the likes of Robert Earl Keen and Reckless Kelly on competing stages at opposite ends of the venerable hall. And it hit Carll like a warm shot of tequila on a hot summer day. “It had been a real low point self-esteem wise, after having been a working musician on Bolivar and in Galveston,” he says. “But for the first time I thought, ‘Here’s something to strive towards. Here’s a scene I could be hanging in.’”

He decided to regroup and return to the family beach house, with the rationale that he could “go back there where at least I can get paid to sing.” But as Gruene Hall faded in the rearview mirror, he began drawing up a plan of attack that would land him center stage at an Americana Jam in the not-so-distant future. Back on the Gulf Coast, Carll continued to open for touring acts at the Old Quarter, while making increasingly more frequent excursions into Houston to boost his regional reputation and begin to build a bigger fan base. He also kept getting kind words from other musicians who were happy to help this laidback guy with a boatload of charisma and bag full of great songs.

Austin’s Trish Murphy was one of those early and enthusiastic supporters of Carll’s. Her endorsement of him on her website would help spread the word to a broader Texas audience and to her fans throughout the country. Murphy, who at that time already had a trio of albums and a Lilith Fair appearance under her belly shirt, first become aware of the relative unknown at a songswap at Houston’s Mucky Duck that had brought together Carll, Murphy and Shake Russell. For Carll, it was a major coup to be paired with with the likes of Murphy and Russell. “To me they were rock stars,” he says, “because even I knew their names. I figured they must be really famous if I was aware of them.”

Murphy shared the excitement over the booking, because she’d been a huge fan of Russell’s for over a decade. Carll was clearly the third wheel going in. That changed, though, once the songs and banter started flying.

“Hayes starts telling everybody — in that distracted, Eeyore voice he has — that he tried to get some better, more famous songwriters on his bill, but that Shake Russell and I were the best he could do,” Murphy recalls with a giggle, still feigning shock at the night’s slight.

“He was genuinely, like by accident, a genius performer,” she continues with a hint of envy and disbelief. “At one point, he rattled off another one of his dead-aim deadpan songs, and I just looked at everybody and said, ‘Who the hell is this young punk?’ I admit it was pure, naked jealously. They all laughed and kept on laughing, probably because they were wondering the same thing. We all knew he had it.”

Years later, after Carll had a few albums of his own in the discography and his name was well-known to Texas music fans, Murphy had him lined up to join her at a songswap at the White Elephant in Fort Worth. As she was driving up I-35 to the show, her phone rang. “It was Hayes calling to bail on me,” she recalls with a laugh, “because he’s still throwing up from his bachelor party the night before.”

(As Carll is reminded of an East Coast show early in his career where half the audience had come to hear him based on Murphy’s recommendation (“Did we talk that night? … Yeah? Cool.”), the door from the garage opens and his family is introduced. When his wife, Jenna, softly asks him, “Don’t you have to be somewhere, Hayes?” it has the ring of a pre-arranged interview escape plan. But Carll shakes his head. “No, no, it’s alright,” he replies. His son dons headphones and starts to play a computer game, the dogs are still being chill in the corner and the ottoman scratch isn’t mentioned. Carll smiles at Jenna as she prepares to leave again, and says sweetly, “Love ya.” And it’s clearly meant.)

In 2002, Carll sent a self-financed demo album to the small Houston label, Compadre Records, which in turn offered him a licensing deal. Lisa Morales, of Sisters Morales, offered to produce his debut album. Carll had endeared himself to Lisa and her sister Roberta when he met them after a Sisters Morales show at the Old Quarter. The show was sold out, and according to Lisa, “Rex wouldn’t let him in.” So he listened to the performance from outside the building. Later, after he got a chance to introduce himself, the Morales sisters and Bell agreed that the next time they played there, he would be opening for them inside and not cooling his heels out front.

Although she had previously only served as producer on Sisters Morales records, Lisa was determined to help Carll make the process of recording his first album as positive as possible — in part because she and her sister had already been through “the old Nashville experience where someone tells you how they’re going to make you sound.” So, before laying down a single note of Flowers and Liquor, Carll and Morales took considerable time discussing the project. “I really watched his body language closely,” she says, “and if it looked like he was even the least bit uncomfortable, I’d offer another idea. At that point in his career, he didn’t really know what he wanted, or how to articulate what he did want.”

Nevertheless, Flowers and Liquor, ended up earning Carll a pretty fair amount of critical praise — and even a few more Townes comparisons. The album’s 11 original songs were all from that beach bum, single guy stage of his life, and while there are well-crafted “flower” songs, such as a tender “Arkansas Blues” and the wistful duet with Morales, “It’s a Shame,” it skews more to the “liquor” songs of weekend benders and the high life. Because he had a licensing deal with Compadre, Carll still owns the rights to the music today. “While it didn’t sell all that well, it got my name on the map in ways I couldn’t have alone and showed me how it all works with the intricacies of record label,” he says.

That knowledge of the business led Carll to turn down an offer from Sugar Hill Records a few years later and opt instead to again self-finance the production, essentially betting on the hope that a better offer would come along from a larger label. Released on his own Highway 87 label, 2005’s Little Rock is “a more compact garage-rock record,” says Carll. The credits features names such as Guy Clark, Adam Carroll, Ray Wylie Hubbard and Allison Moorer, a testament to his growing stature in the business at the time of his sophomore effort.

Carll’s bet proved a good one, and he eventually signed with Lost Highway Records, putting him among a bravo company of artists that includes Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Lucinda Williams and Ryan Bingham. The label released Carll’s third album, Trouble in Mind, in early April 2008.

But then, just as Carll began an intensive tour to promote that breakthrough album, which would eventually garner him an Americana Music Association Song of the Year Award (for “She Left Me for Jesus”) and favorable notices in national publications ranging from People to Playgirl — fate crept up and whispered in his ear once again, reminding him that it, too, had some trouble in mind.

***

Soldiering On

A few weeks into a year of touring to promote Trouble in Mind, Carll was playing a show in New York City, when his voice simply failed him. “I was doing a song and just missed the note, and thought, ‘That’s odd, that’s never happened to me before.’”

What he initially believed to be an anomaly would become a nightly occurrence. As the touring went on and on, his vocal chords — a pretty essential weapon in a singer-songwriter’s arsenal — were getting progressively stressed and strained. To the point that Carll had what he describes as a ceiling on his voice that greatly limited his range and song options.

“I used to love singing, and enjoyed it because I could do it with energy,” Carll says. “I never thought I had a great voice, but I could scream or do the John Lennon howl. I stopped being able to do those things. So it meant I was limited.”

He was fine, he says, if he started on a high note and stayed there, but he couldn’t “swoop up, which is a lot of what I do, particularly in a song like ‘Drunken Poet’s Dream.’” A song that just happened to be one the fans expected him to do each and every night.

Fate’s ironic twists and turns weren’t lost on a fellow who’d cut his teeth doing Dylan covers in colorful dive bars on Texas’s Bolivar Penisula. “I’d sang my ass off for two people in a shrimper bar, and now I’m on Austin City Limits, or playing with John Prine, or out in front of 20,000 people, and I can’t carry a note,” he says. “Here I was, getting the most exposure I ever had, but I also was at my lowest physically. It was a pretty bleak time.”

Carll was forced to alter the way he performed some of his own songs, jettison others all together, and essentially come up with sonic workarounds that he hoped would mask the problem. The whole experience not only made every stop on the tour a struggle, it left Carll questioning his long-term staying power in the business. “It was really bothering me, because this is my livelihood,” he says. “And it made it not fun. I was going out and it was like a job, which I never wanted it to feel like. It was a weird kind of emotional rollercoaster to be on.”

But Carll soldiered on, as his longtime friend and occasional collaborator, John Evans, says admiringly. “Hayes is a fighter,” Evans says, “and he doesn’t want to let anyone down. The last thing he wanted to do was go out and let down any of the fans who’d come to see him. That was a tough deal for him.”

But fans eventually would notice. After one Austin show, a concerned fan posted this comment online: “I will say that although I’m a HUGE Hayes Carll fan, the last few times I’ve seen him (including this time), his voice just hasn’t been there. It’s always been raspy and gritty (which I love), but I’m hoping the road isn’t catching up to him too much.

Carll’s manager, Mike Crowley, suggests that part of the problem stemmed from a nearly two-fold increase in the number of shows he was used to doing. In addition, Carll was also touring with a full-bore rock band, which required him to sing differently than he had before in live settings.

Grizzled road veteran Ray Wylie Hubbard had another theory. “I told him to quit drinking and quit smoking,” Hubbard says. “And I think that’s what the doctor told him, too.”

It was. Since making the prescribed lifestyle changes, Carll has gained a new appreciation for the tenuous nature of success and career survival. “I’m no saint,” he allows, “but I’m trying to take care of my ability to earn a living. And to do this for fun.”

Recovery has entailed a regimen of vocal lessons, learning proper warm-ups, staying hydrated (with good ’ol H20), and medicine for acid-reflux which doctors told Carll could be a major cause of vocal chord strain.

“I’ve taken terrible care of myself over the years,” Carll says, “and that was part of the fun of it. Because this is one job where you can drink, smoke, not sleep, yell and look like shit all the time, and nobody seems to care. But at a certain point, you want to be in it for the long haul.”

Now, as Carll sets out on another whirlwind tour of duty to promote yet another critically-acclaimed album, he’s relieved to be hearing more of his old self in the stage monitor. “I feel it coming back,” he says happily, “and I’m like, ‘Yeah, that’s what I used to sound like.”

***

Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition

At every stop of the Trouble in Mind tour, Carll dutifully performed the track that was receiving the most airplay, “She Left Me For Jesus.” The song — a co-write with Brian Keane — has become a signature of sorts for Carll, and the only one many casual music fans across the country may know him from. Talk radio personality Don Imus somewhat hyperbolically dubbed it “the best country song ever.” Naturally, as often seems to be the case with such watershed songs, the track almost didn’t even make it onto the album.

“I told him not to put that song on there,” says Hubbard. “That’s one thing I tell people. Right after you write a song, ask yourself, ‘Can I sing this for 38 years?’”

As the writer of “(Up Against the Wall) Redneck Mother,” Hubbard knows something about the burden of dragging your own personal “American Pie” around for decades. Carll listened, but ultimately rejected the Wylie Lama’s sage advice. Still, he admits it was a tough call. “I sure don’t want to be known as a guy who just wrote a tongue-in-cheek, somewhat blasphemous joke song,” Carll says. “That wasn’t my dream.”

Only time will tell how burdensome that joke song will prove to be in the long run. But for now, Carll likes to think of it less as an unwanted albatross of a calling card, and more like the welcome mat that brought so many new fans to the rest of Trouble in Mind — and hopefully, by extension, KMAG YOYO and everything still to come. “Besides,” he adds, “I don’t even play that song half the time I play anymore. There was a woman at a free show in Austin who was yelling at me because I didn’t sing it. So I offered to give the lady her money back — even though it was a free show.”

***

Danger, Love and Money

“They say, ‘Boy you ain’t a poet,

just a drunk with a pen.’

Over and over, again and again

Lord, they don’t know

about the places I’ve been

It gets hard out here”

— “Hard Out Here,” from KMAG YOYO (& Other American Stories)

When Carll went into the studio to record KMAG YOYO, he says he trusted his instincts more than he ever had in the past. “This is the first time I kind of said, ‘Fuck it, I just want a record that’s as much fun and meaningful as I can make it.’ Not that I’ve ever cared too much how things are going to be perceived, but this time I really didn’t think about it at all.”

What he clearly did think about, though, was rising to the challenge of writing to his full potential — and responsibility. Having a family, a mortgage and health-related wake-up calls tend to sober one up. As a result, Carll’s songwriting on his new album is coming closer to the mark he’d hoped to make with his art all along.

“The early Dylan stuff is what got me into music in the first place,” Carll says, “so I kind of envisioned that I was gonna be this lyrical bringer of change who was going to spell things out for everybody in a brilliant way that was going to make the the world a better place. But I found it was a lot easier for me to just rhyme stuff that had to do with whiskey.”

Don’t worry — there are still plenty of punch lines, semi-automatic words at play and shout-outs to booze to be heard here. But KMAG YOYO ultimately finds Carll playing the weary and introspective poet more than the knee-slapping drunk with a pen. “He has grown as a writer,” Hubbard observes. ”As he’s matured … well, I don’t think he’s matured at all, scratch that! But as he’s aged, he’s developed a conscious.”

If Trouble in Mind was Carll’s introduction to a national audience, KMAG YOYO is a declaration of his intent to hunker down, stay while, and maybe finally get started on that “making-the-world-a-better-place” mission. Although Carll doesn’t view it as a political record, per se, it does reflect some of the hard-luck characters and American stories he’s come across during his travels. The military acronym “KMAG YOYO” stands for “kiss my ass, guys, you’re on your own.“ But here, it’s more of a battle cry — and an homage to all the uncommon men and women with whom Carll relates and respects. People who, perhaps through no fault of their own, may have lost their jobs, lost loves, lost faith or lost hope —but who nontheless find a way to carry on. They “Stomp and Holler” out their frustrations, and then shout right back at the bullshit thrown their way with a full-throated, “No, you kiss MY ass!”

“One of these days,

I’m gonna find my way

or else just disappear

I’m out here in the filth and squalor

and all I wanna do

is stomp and holler”

— “Stomp and Holler,” from KMAG YOYO

“You meet people every night and hear their stories and you can tell that they’re having a hard time economically,” Carll says. “Politically, the level of discourse is at a troublesome level where people are just sort of yelling at each other. And, of course, we have two wars going on … this is the first time I’ve tried to paint some of those stories about what’s going on.”

***

Band of Brothers

Prior to the album’s release in February, Carll gave a few soldier acquantices an advance listen to the KMAG YOYO’s adrenaline fueled title track, because he wanted to make sure it passed muster with the real-life American G.I. Joes and Janes he so admires. His manager, Crowley, too, was assured that his client was on terra firma with those in uniform when he shared the song with a veteran he was seated next to on a flight. “He laughed his ass off,” remembers Crowley.

So, don’t be surprised if the rollicking rocker that unabashedly owes its groove to Dylan’s classic “Subterranean Homesick Blues” finds its way onto the iPods and iPads of thousands of servicemen and women with the homesick blues. Crowley says there’s also hope that Armed Forces Radio will embrace the song and that Carll will be able to perform it at U.S. military bases or on a USO tour.

Songwriters are always being asked “What comes first?” It’s long been Carll’s method to write the lyrics and then bang around on the guitar in search of the music. With KMAG YOYO, however, he approached it differently. “I wanted this record to be more musical and for me to add the imagery to the groove rather than vice versa. So a lot of these tracks we recorded music first, and then I went in and sort of wrote to that palette.” The title song emerged from a riff that Scott Brown, Carll’s lead guitarist on the road, kept playing at soundchecks. In the studio, the band recorded the fully developed music first and then “we hit ‘record’ and it was me singing in a stream of consciousness,” says Carll. “In that setting, you don’t have time to think, ‘Oh, this doesn’t work.’ You fuckin’ go with it.”

“How the hell’d I get here?

Blastin’ through the atmosphere

Drop the rocket boosters

and I’m shifting into high gear.”

— “KMAG YOYO,” from KMAG YOYO

With Carll spewing out the first words that sprang to mind — “spaceship,” “Afghanistan,” “acid” — he liked where it was going, but needed some help in getting there. “I just kept thinking about what was the most intense thing you could be doing,” he explains. “Maybe you’re in a battle situation. Or maybe you’re on a spaceship. Or on a spaceship on LSD. That’s pretty heavy, you know, and this sort of stuff just kept coming.” After taking the recorded track home to ponder what all this intensity could mean, he called in reinforcments, Brown and Evans, to help thread together the story of a disillusioned G.I. who ends up a guinea pig in very high orbit. “The 50 percent came in 10 minutes, but the rest of it took three or four days to work through and make it all sort of make sense,” Carll says, emphasizing the “sort of.”

“KMAG YOYO” was the song Carll performed on his Tonight Show debut, and the venerable stage has rarely been rocked so hard. “It was like guitarmageddon,” raves Evans, who isn’t part of Carll’s touring band these days. But Hayes wanted his co-writer and neighbor to share the spotlight with him. Evans cherished the gesture. “Just out of the freakin’ goodness of his heart, nice guy that he is, he invited me to come and play with him. That’s a pretty darn good friend when you get your first shot at the Tonight Show and you go and ask one of your buddies to jump on stage with you.”

But before they took the stage, there were several costume changes in the Carll dressing room. “You should have seen him backstage,” Evans reveals with a laugh. “Hayes is really meticulous about how sloppy he dresses. He must have tried on 10 different wrinkled plaid shirts. But I guess that’s the look he’s goin’ for.”

That distinctive Carll sartorial style can be seen on the big screen, too — just not on him. In the recent Gwyneth Paltrow movie, Country Strong, which features four of Carll’s songs, Garret Hedlund’s character, Beau Hutton, represents the anti-Nashville songsmith. The movie’s director and music supervisor liked Carll’s personal style and saw them as elements that could give the Hutton character greater authenticity.

Carll was a bit taken aback when he visited the set one day and saw pictures on himself all around Hedlund’s wardrobe chair as a benchmark for the actual look they were striving to achieve. But despite his personal style being grafted onto Paltrow’s love interest, when he went to the movie’s wrap party, few of the people who worked on the film together for months knew who the Beau Hutton-looking character really was. While Carll kept acting naturally and listening to the band performing one of his songs, the sting of being unrecognized was lessened when Gwyneth Paltrow herself came up and asked him to dance.

***

Sleeping with the Enemy

Speaking of fictional romantic interests and unlikely dance partners, there are a few good old-fashioned songs about love and L-U-S-T on KMAG YOYO, too. The female protagonist of “Another Like You” could easily be the rebound woman you’d gravitate to if you’d really been dumped for Christ Almighty. The song blends those trusty Carll staples of humor and alcohol with his more recent, ripped-from-today’s-headlines current affairs musings. He admits to spending a lot of time on news chat boards (“I ought to stop, because it’s usually everyone yelling at each other, but I’m always just hoping that someone will have a valid point”) and occasionally tuning into conservative shows just to hear their varying positions.

In fact, the genesis of “Another Like You,” which Don Imus may someday soon call “the greatest country duet since ‘Jackson,’” was Carll picturing conservative pundit Ann Coulter sitting at a bar and a guy trying to hit on her. “The first line came to me — ‘smokin’ on a cigarette, talkin’ ‘bout the deficit’ — and I played with it for a while,” Carll says. “But it got kind of boring because it was just describing her throughout the song. Then I thought that she needed a foil, because she can probably give it right back. So I put myself in the song, and it was a fun exercise. I got to step out of me and sit with a pen and sort of insult myself. The idea, once it got going, was that alcohol and sexual attraction can overcome any political divide.”

“You was openly frustrated

you said Dylan’s overrated

while singing ‘Tangled Up in Blue’

I don’t know what I was thinkin’

I can feel my heart a’ sinkin’

I never seen a fella like you.”

— “Another Like You,” from KMAG YOYO

Carll was originally going to call the song “James and Mary,” after one of our country’s oddest political couples, Demorcrat and former Clinton campaign strategist James Carville, and his wife, Republican consultant and former Bush aide, Mary Matalin. Carll hopes the two will agree to make an appearance in a video for the song. When it came time to record the duet, big names like Gillian Welch and Lucinda Williams were initially floated. But Carll had met a singer named Cary Ann Hearst when she and her husband, Michael Trent, opened a show for him, and was duly impressed. “She was, like, way better than I was,” he confesses. No doubt remembering how he’d benefitted from more established performers giving his career a jumpstart, Carll decided to tap her on the shoulder to play the part of the brassy Ann/Mary.

***

From Here to Eternity

It’s Carll’s hope that KMAG YOYO represents a new phase in his career. With the greater exposure that comes from national television appearances and having his songs featured on movie soundtracks, he’s no longer just a songwriter’s songwriter; he’s achieving the type of commercial success that has all too often alluded some of our best. It’s a tricky transition, but so far — so good. Carll notes that he’s taken solace in something Jack Ingram told him years ago.

“He told me one time,” Carll recalls, “‘You know, there’s career and there’s art. And they’re two different things. My career got ahead of my art, and I’d like to think it’s caught up. Your art is ahead of your career and you can’t control how that happens. You just hope they’re both strong at the end of the day.’”

Or, to put a finer point of it, it’s nice to be compared to Townes, but it’s even nicer to have mailbox money and royalty checks made out to Hayes Carll.

“At one time, all I cared about was the appreciation of other songwriters,” Carll says. “And then at a certain point it’s, I’m tired of being broke, and nobody’s hearing these songs I’m writing. So you want it to equal out.”

And if it doesn’t, well … maybe he can dust off his old theater chops, give Gwyneth a call and look into exploring a little more of that film stuff. After all, he’s already turned in a very convincing performance in the role of “boom operator” in the music video for “She Left Me For Jesus,” so why not think about a little acting career? Call it an idle fantasy at the moment, or maybe a daydream at most, but hey — he’s had pretty good luck with those in the past.

It could happen.

In fact, Carll just auditioned for a starring role in a pilot, written by none other than Ray Wylie Hubbard, that’s to be filmed in Texas. The lead character in the project is a folk singer — a folk singer who goes by name of Hayes Carll, coincidentally enough. When Carll learned of this fortuitous stroke of fate, he told Hubbard he’d really like to be considered for the part.

“Well, you can,” Hubbard replied skeptically. “But you’re really gonna have to act. Because this Hayes Carll is a lot cooler than you.”

With any luck, Hayes Carll just could be the next Hayes Carll.

No Comment