By Eric Hisaw

(LSM Jan/Feb 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 1)

Johnny Cash came roaring out of an Arkansas cotton patch, a Jesus-conflicted, lanky black-haired rebel, a touch more worldly from a stint in the Air Force, with a song in his heart, a rhythm in his wrist and a voice no one had ever heard before. He showed up at Sun Records in Memphis, home first to Howlin’ Wolf and Ike Turner before unleashing Elvis Presley on the unsuspecting masses, wanting to cut records. Legend has it he wanted to record gospel music, though showing up at Sun for such an endeavor in the midst of Bible-soaked Tennessee seems like an odd choice. Cut records he did though, creating a powerful and distinct body of work and consistently competing with A-list Nashville stars for space on the radio.

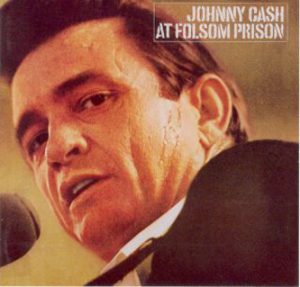

At some point Sam Phillips and Sun could no longer handle their superstar roster and, in the interest of developing more talent, let three of its big four go to major labels and watched the youngest and wildest of the young and wild, Jerry Lee Lewis, self destruct. Elvis went to RCA, seeing his intensity level drop with every release until he was self-caricaturized into B-movie fluff. Carl Perkins was slowed down by a horrific car accident and though his creative spark burned bright at Columbia Records, he never regained his commercial appeal. Johnny Cash, on the other hand, took his move to Columbia as an opportunity to not only indulge his gospel passion, but also to craft concept albums that delved deep into a fading Americana, bring street-level songwriters like Kris Kristofferson, Pete LaFarge, and Vince Mathews to prominence, and to have mega-hit records of a magnitude a regional label like Sun could only dream of. Over a fruitful span of 32 years — the bulk of his recording career — Cash would make a whopping 59 full-length albums and dozens of singles for Columbia, covering the gamut from earnest gospel, protest folk, and novelty records to canonized, stone-cold classics like 1968’s At Folsom Prison.

Despite his legendary status, Cash’s epic run with Columbia came to a rather ignominous end in the mid-80s, when then label president Rick Blackburn dropped the 55-year-old artist like a hot potato to focus on new acts. Cash closed out the ’80s and entered the ’90s with Mercury Records, though the four albums he recorded for that label went largely unnoticed. It wasn’t until he teamed with producer Rick Rubin for 1994’s spare and powerful American Recordings (for Rubin’s label of the same name) that Cash’s music began to resonate again on a scale worthy of his iconic name and voice. Cash and Rubin would record several more albums together to considerable acclaim, right up to — and beyond — Cash’s death in 2003.

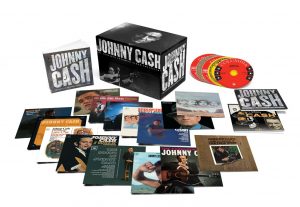

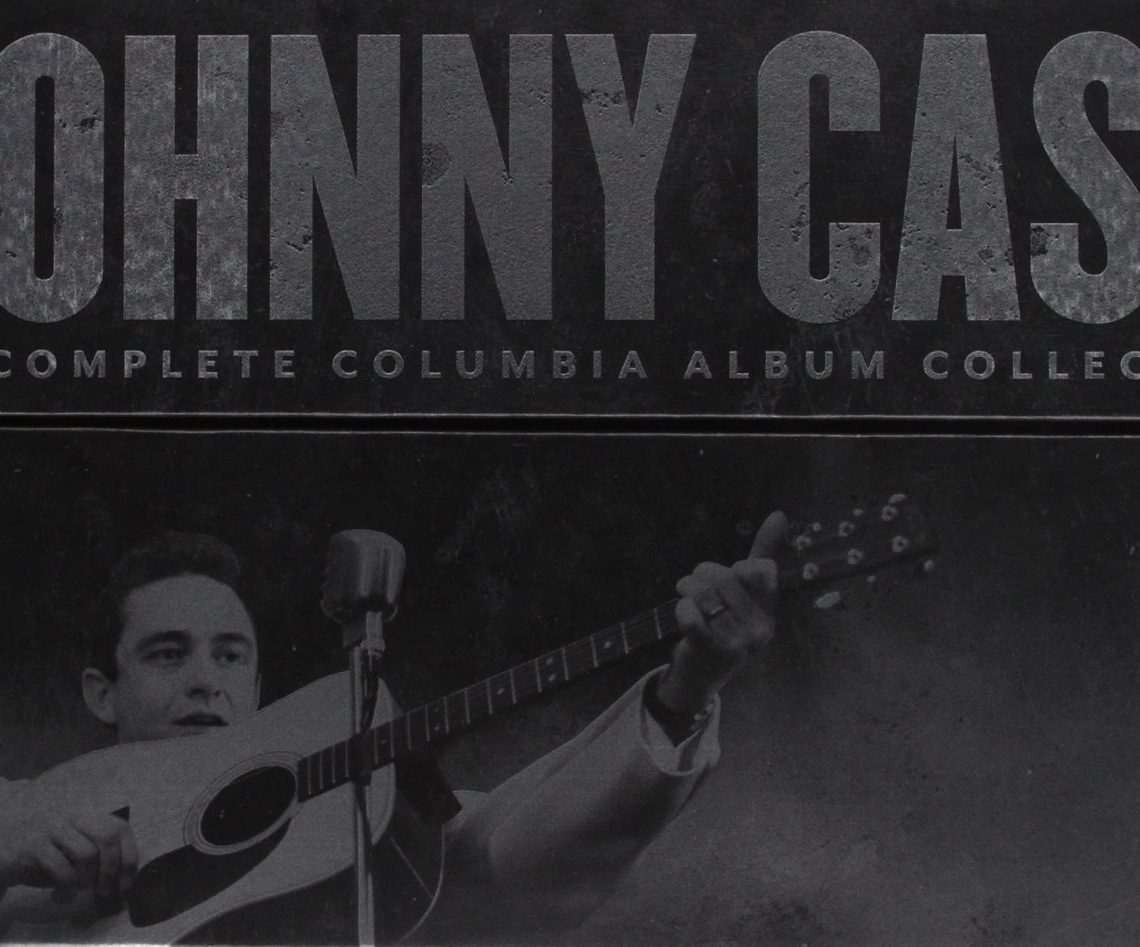

Ten years after his passing, Cash’s standing as one of the most influential American artists of the last century is unassailable. But although his myriad greatest hits collections, consensus landmark albums and swansong recordings for Rubin continue to sale and connect with new generations of fans, large chunks of his original catalog have never been reissued since their original release. That is, at least, until now. With the December 2012 release of Johnny Cash: The Complete Columbia Album Collection, diehard fans of the Man in Black finally have access to a body of work that took Cash himself the better part of a lifetime to create — and that would likely take a collector just as long to piece together over years of combing through used vinyl bins. I speak from experience: As a Cash fan and afficiando of finding and buying vinyl (I’ll save the word “collector” for that special breed), a third of what is in this box has taken me 25 years to find.

Ten years after his passing, Cash’s standing as one of the most influential American artists of the last century is unassailable. But although his myriad greatest hits collections, consensus landmark albums and swansong recordings for Rubin continue to sale and connect with new generations of fans, large chunks of his original catalog have never been reissued since their original release. That is, at least, until now. With the December 2012 release of Johnny Cash: The Complete Columbia Album Collection, diehard fans of the Man in Black finally have access to a body of work that took Cash himself the better part of a lifetime to create — and that would likely take a collector just as long to piece together over years of combing through used vinyl bins. I speak from experience: As a Cash fan and afficiando of finding and buying vinyl (I’ll save the word “collector” for that special breed), a third of what is in this box has taken me 25 years to find.

To call the Complete Columbia Album Collection massive is an understatement. The bulk of this collection — 62 discs and 863 tracks in all! — is so vast that it is almost impossible to fairly digest. Like so many of his contemporaries — including Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, George Jones, and Merle Haggard — Cash probably made too many albums. In the 1950s and ’60s the mode of operation in Nashville was quantity first. Artists would come off the road and slip into one of the major studios with an assembly of A-list players ready to roll tape, cut four songs in three hours and be on their way back on the road to a highschool auditorium for a show that night in Paducah, Ky. But although he turned out no less material, Cash for the most part took a different approach from the status quo, using his distinctive band on most of his recordings and putting together long players that were tied together in theme.

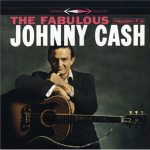

He began his Columbia career with 1958’s unassumingly titled The Fabulous Johnny Cash, an album that for all practical purposes was an extension of what he had done at Sun. The record featured “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town,” a Western hit that fit right in with such earlier singles as “I Walk the Line” and “Folsom Prison Blues.” But Columbia had offered him creative freedom when he signed his papers, and he put that promise to the test straight away with his second album for the label, 1959’s Hymns By Johnny Cash.

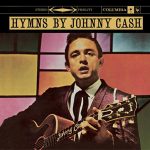

He began his Columbia career with 1958’s unassumingly titled The Fabulous Johnny Cash, an album that for all practical purposes was an extension of what he had done at Sun. The record featured “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town,” a Western hit that fit right in with such earlier singles as “I Walk the Line” and “Folsom Prison Blues.” But Columbia had offered him creative freedom when he signed his papers, and he put that promise to the test straight away with his second album for the label, 1959’s Hymns By Johnny Cash.  Featuring a few Cash-penned originals mixed in with traditional gospel fare, the album offered early proof that no matter what genre or topic Cash wanted to tackle, his one-of-a-kind sound would still carry through. Even Cash’s most devout gospel songs were delivered with all the sweat-soaked, train-beat chugging rhythms of his biggest hits.

Featuring a few Cash-penned originals mixed in with traditional gospel fare, the album offered early proof that no matter what genre or topic Cash wanted to tackle, his one-of-a-kind sound would still carry through. Even Cash’s most devout gospel songs were delivered with all the sweat-soaked, train-beat chugging rhythms of his biggest hits.

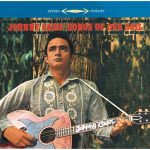

Hymns By Johnny Cash didn’t launch any hit singles of its own, but Columbia’s allegiance to its new star was undeterred. Songs of Our Soil and Now There Was a Song! followed in quick succession, all within 12 months in 1959/60, the former featuring a slew of original songs soaked in rural Americana imagery and the latter a run through covers of hits by other country artists. Nothing exemplified the absolute individuality of the Cash Sound like hearing him run through songs associated with more traditional singers like George Jones, Hank Williams and Marty Robbins. Of note is the first Cash take on his punk-rockish, crowd-pleasing “Cocaine Blues,” a Western swing number first cut by Roy Hogshead, rendered here with the more family friendly title of “Transfusion Blues.” More theme albums followed at an amphetamine pace: Ride This Train (1960), Hymns from the Heart (1962), and Blood, Sweat and Tears (1962) are all self-explanatory explorations of the American spirit. The Sound of Johnny Cash (1962) and Ring of Fire: The Best of Johnny Cash (1963) are both deceptively titled yet fine albums. The Sound makes much use of Floyd Cramer’s decidedly non-Cash-sounding piano and features only two Cash-penned originals, but it does give us the first pass at the creepy and violent “Delia’s Gone,” raising the bar for Cash material with an edge. Ring of Fire is really nowhere close to a “best of” package, but its mix of a little old (albeit re-recorded) and mostly new songs did yield some enduring classics.

Hymns By Johnny Cash didn’t launch any hit singles of its own, but Columbia’s allegiance to its new star was undeterred. Songs of Our Soil and Now There Was a Song! followed in quick succession, all within 12 months in 1959/60, the former featuring a slew of original songs soaked in rural Americana imagery and the latter a run through covers of hits by other country artists. Nothing exemplified the absolute individuality of the Cash Sound like hearing him run through songs associated with more traditional singers like George Jones, Hank Williams and Marty Robbins. Of note is the first Cash take on his punk-rockish, crowd-pleasing “Cocaine Blues,” a Western swing number first cut by Roy Hogshead, rendered here with the more family friendly title of “Transfusion Blues.” More theme albums followed at an amphetamine pace: Ride This Train (1960), Hymns from the Heart (1962), and Blood, Sweat and Tears (1962) are all self-explanatory explorations of the American spirit. The Sound of Johnny Cash (1962) and Ring of Fire: The Best of Johnny Cash (1963) are both deceptively titled yet fine albums. The Sound makes much use of Floyd Cramer’s decidedly non-Cash-sounding piano and features only two Cash-penned originals, but it does give us the first pass at the creepy and violent “Delia’s Gone,” raising the bar for Cash material with an edge. Ring of Fire is really nowhere close to a “best of” package, but its mix of a little old (albeit re-recorded) and mostly new songs did yield some enduring classics.

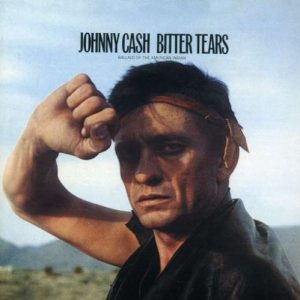

By this point in his career, Cash had already become a household name and a bonafide personality. That could only mean trouble for a creative force. The first sign of celebrity infecting a country western singer is usually the recording of a Christmas album; the second is marriage to another famous personality and/or duet albums; and the third is re-recordings of your earliest hits. Cash made good on all three with his next few releases: The Christmas Spirit (1963), Keep on The Sunny Side: The Carter Family with Special Guest Johnny Cash (1963), and I Walk The Line (1964). And yet, just as he seemed on the verge of tripping headlong over that fine line of self parody (as so many of his contemporaries had or would soon enough), Cash delivered one of the most striking and fearless statements of his career via 1964’s Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. Propelled by Cash’s iconic take on Pete LaFarge’s fantastic “Ira Hayes,” this decidedly unconventional (certainly for the country music genre!) protest album about the plight of Native Americans climbed all the way to No. 2 on the charts.

By this point in his career, Cash had already become a household name and a bonafide personality. That could only mean trouble for a creative force. The first sign of celebrity infecting a country western singer is usually the recording of a Christmas album; the second is marriage to another famous personality and/or duet albums; and the third is re-recordings of your earliest hits. Cash made good on all three with his next few releases: The Christmas Spirit (1963), Keep on The Sunny Side: The Carter Family with Special Guest Johnny Cash (1963), and I Walk The Line (1964). And yet, just as he seemed on the verge of tripping headlong over that fine line of self parody (as so many of his contemporaries had or would soon enough), Cash delivered one of the most striking and fearless statements of his career via 1964’s Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. Propelled by Cash’s iconic take on Pete LaFarge’s fantastic “Ira Hayes,” this decidedly unconventional (certainly for the country music genre!) protest album about the plight of Native Americans climbed all the way to No. 2 on the charts.

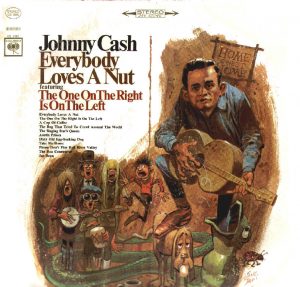

An album like Bitter Tears may have been an anomaly on the country charts in the early ’60s (just as it still would be today), but it really wasn’t out of character for Cash at all. Despite being identified as a country Western performer — and dominating the genre’s charts for years on end — Cash never did fit the mold. Outside of a few random covers, he rarely recorded anything in the dancehall drinking and cheating vein; his songs were much more in the ballad form, so it was only natural that he would have an ear turned toward what was happening in the folk revival. What was happening was a young guy full of the same kind of rollicking rhythms and energetic edge named Bob Dylan. On 1965’s Orange Blossom Special, Cash paid homage and made a C&W hit out of Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe” with his wife-to-be, June Carter, and an enduring favorite of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” a song seemingly tailor-made for his booming voice. Later that same year, he released another concept album, Johnny Cash Sings the  Ballads of the True West. Steeped in Americana folklore, the original double album contained mostly Cash originals but also a cover of Ramblin’ Jack Elliot’s “Mister Garfield,” further firming up his relationship with the folk scene. (A scaled-back, single-LP version of Ballads of the True West was released the following year, retitled Mean as Hell). Another Ramblin’ Jack song, “Cup of Coffee,” was featured on 1966’s Everybody Loves a Nut (with Elliot himself guesting on the track.) True to the spirit of the Jack Clement-pennted title track, Everybody Loves a Nut was a light-hearted album of humorous tunes, including the goofy hit “The One on the Right Is on the Left” — another Clement tune that found Cash taking a good-natured stab at the very folk world he was borrowing from, singing lines like “Don’t go mixing politics with the folk songs of our land” with a knowing wink.

Ballads of the True West. Steeped in Americana folklore, the original double album contained mostly Cash originals but also a cover of Ramblin’ Jack Elliot’s “Mister Garfield,” further firming up his relationship with the folk scene. (A scaled-back, single-LP version of Ballads of the True West was released the following year, retitled Mean as Hell). Another Ramblin’ Jack song, “Cup of Coffee,” was featured on 1966’s Everybody Loves a Nut (with Elliot himself guesting on the track.) True to the spirit of the Jack Clement-pennted title track, Everybody Loves a Nut was a light-hearted album of humorous tunes, including the goofy hit “The One on the Right Is on the Left” — another Clement tune that found Cash taking a good-natured stab at the very folk world he was borrowing from, singing lines like “Don’t go mixing politics with the folk songs of our land” with a knowing wink.

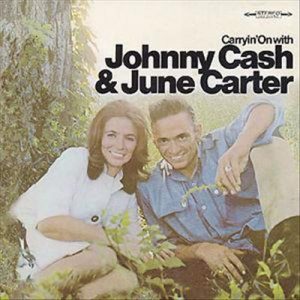

The playful spirit of Everybody Loves a Nut aside, Cash was actually in a state of personal decline in ’66. Fueled by amphetamine abuse, he took on a gaunt and dishevled appearance and stumbled through a period of drug busts and erratic behavior. The records kept coming, though, and despite his apparent best attempts to alienate the country music world via his negative publicity, so did the hits. Although it’s long been out of print, Happiness Is You (1966) was another Top-10 charter; it’s the kind of forgotten gem that really makes the Columbia box set so worthwhile. The album finds the Tennessee Three aided by both old-time music master Norman Blake, who was making regular contributions to Cash’s work, and keyboardist Bill Purcell, who brought a hefty dose of electric piano and organ unlike anything previously heard on a Cash recording. The single “Happy to Be with You” is borderline psychedelic.  And though the following year’s Carryin’ on with Johnny Cash & June Carter and 1968’s From Sea to Shining Sea showed an almost unrecognizably thin Cash on their cover photos, both albums have their fair share of memorable moments. Carryin’ On featured both the classic “Jackson” and a noteworthy take on Richard and Mimi Farina’s “Pack Up Your Sorrows.” The patriotic-themed From Sea to Shining Sea (making its debut on CD in the box set), meanwhile, offered up an entire album’s worth of brand new originals from Cash’s own pen.

And though the following year’s Carryin’ on with Johnny Cash & June Carter and 1968’s From Sea to Shining Sea showed an almost unrecognizably thin Cash on their cover photos, both albums have their fair share of memorable moments. Carryin’ On featured both the classic “Jackson” and a noteworthy take on Richard and Mimi Farina’s “Pack Up Your Sorrows.” The patriotic-themed From Sea to Shining Sea (making its debut on CD in the box set), meanwhile, offered up an entire album’s worth of brand new originals from Cash’s own pen.

Before he could hit rock bottom, Cash beat the addiction and pulled off another feat only he could. Taking the Tennesse Three — along with old pal Carl Perkins — into California’s notorious Folsom Prison to cut a live album with the Carter  Family’s soothing presence and support from his touring mates the Statler Brothers, Cash combined the rough-hewn rebellious material that would make him a punk-rock idol in the ‘90s with religious and romantic material delivered with June and a few humorous numbers thrown in. The legendary At Folsom Prison (1968) opens — naturally — with “Folsom Prison Blues,” a chesnut from Cash’s Sun days resurrected into a No. 1 hit (complete with the calling-card introduction that fans everywhere would quiver in their seats waiting to hear for decades to come: “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.”) On this rollicking set of tunes, “Cocaine Blues” is restored to its previous title, fitting right in with a host of crime and punishment tunes — “Green, Green Grass of Home,” “25 Minutes to Go,” “Greystone Chapel,” etc. — performed for their most appropriate audience. Not for nothing is this one of the most highly acclaimed — and beloved — live albums of all time, and not just by country fans. Of course, if Nashville ever had a tried-and-true business plan, it was striking while the iron was hot, so Columbia was quick to follow At Folsom with another live prison album from the equally dangerous San Quentin, along with a fine studio album titled Hello, I’m Johnny Cash (1970). (Note: Although both At Folson Prison and ’69’s At San Quentin have been reissued as expanded “Legacy Editions” with previously unreleased bonus tracks from their respective concerts, the versions included in the Columbia box set revert back to the original track lists.)

Family’s soothing presence and support from his touring mates the Statler Brothers, Cash combined the rough-hewn rebellious material that would make him a punk-rock idol in the ‘90s with religious and romantic material delivered with June and a few humorous numbers thrown in. The legendary At Folsom Prison (1968) opens — naturally — with “Folsom Prison Blues,” a chesnut from Cash’s Sun days resurrected into a No. 1 hit (complete with the calling-card introduction that fans everywhere would quiver in their seats waiting to hear for decades to come: “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.”) On this rollicking set of tunes, “Cocaine Blues” is restored to its previous title, fitting right in with a host of crime and punishment tunes — “Green, Green Grass of Home,” “25 Minutes to Go,” “Greystone Chapel,” etc. — performed for their most appropriate audience. Not for nothing is this one of the most highly acclaimed — and beloved — live albums of all time, and not just by country fans. Of course, if Nashville ever had a tried-and-true business plan, it was striking while the iron was hot, so Columbia was quick to follow At Folsom with another live prison album from the equally dangerous San Quentin, along with a fine studio album titled Hello, I’m Johnny Cash (1970). (Note: Although both At Folson Prison and ’69’s At San Quentin have been reissued as expanded “Legacy Editions” with previously unreleased bonus tracks from their respective concerts, the versions included in the Columbia box set revert back to the original track lists.)

At San Quentin may have given both Columbia and Cash fans exactly more of what they wanted, but Cash himself still made it a point to do exactly what he wanted. Case in point, in between the two prison albums, he gave the fans and label probably the last thing they were asking for: an ambitious concept album (complete with spoken word narratives) about his family’s visit to Israel. Aside from the Carl Perkins-penned classic, “Daddy Sang Bass,” The Holy Land (1968) made little impact. Sadly, it was the last recorded work of guitarist Luther Perkins, who passed away from injuries sustained in a house fire. He was replaced by Oklahoman Bob Wooten, who had studied Luther’s style so closely it is nearly impossible to tell who played on what, and the show went on.

Buoyed by the success of Folsom Prison and San Quentin, Cash entered the ’70s more popular than ever — and with his own ground-breaking weekly TV show, to boot. A tie-in album, The Johnny Cash Show (1970), hit No. 1 on the strength of its fantastic, Kris Krisofferson-penned single, “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Cash recorded his first two Kristofferson covers (including “To Beat the Devil”) on the preceeding Hello, I’m Johnny Cash, and the rest of Cash’s career would find him returning again and again to the West Point-educated Texas songwriter and burgeoning movie star for some of his best material. Of course, Cash was still capable of writing his own indelible classics, as proven with the folky hit “Flesh and Blood,” which was featured on his 1970 soundtrack for the movie I Walk the Line, starring Gregory Peck and Tuesday Weld. No hits but some tasty, funky guitar picking by Carl Perkins makes the soundtrack to the more obscure Robert Redford flick Little Fauss and Big Halsy (also from 1970) a real treat.

“Flesh and Blood” would not be Cash’s last iconic hit single of the ’70s — no less a classic than “Man in Black,” from the 1971 album of the same name, was waiting just around the corner — but his run of bonafide hit albums would peter out before the decade’s end. The problem was, he was just too famous: as a television star and household name, Cash’s availability to his fans through media outlets other than radio and recordings created a serious drop in demand for his official LP releases. As such, apart from the odd charting single here and there, most of his albums throughout the rest of the decade (and pretty much all the way up until his Rick Rubin-produced “comeback” in the ’90s) came and went with little of the fanfare accorded his earlier output. Most of the first-time-on-CD titles in the Columbia box come from this period, and therein lies the collection’s greatest appeal for dedicated fans. Addmittedly, some of those albums hold up only as the novelty/curios they were in the first place — including 1972’s narrative-threaded America: A 200-Year Salute in Story & Song; 1973’s double-album Jesus movie soundtrack The Gospel Road; two more Christmas albums and a children’s album — but even the biggest Cash fan is likely to find gems here that they’d never heard before. A Thing Called Love (1972), with its Jerry Reed-penned title track and Marty Robbin’s “Kate,” features some of the hardest-driving music Cash had released since the ’50s. Any Wind That Blows (1973) is a consistently strong, acoustic-oriented record with some very cool under-heard tracks, like Roy Orbison’s “Best Friend,” an energetic take on “If I Had a Hammer” and Cash’s first recording of “Country Trash,” an original he would revisit on 2000’s American III: Solitary Man. The unfortunately titled Johnny Cash and his Woman (1973) is less successful, with its Tennessee Three-styled take on Charlie Rich’s “Life’s Little Ups and Downs” proving to be a better idea in theory than in execution.

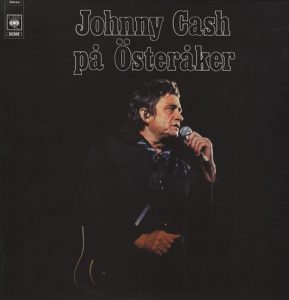

Pa Osteraker, a 1973 album recorded live in a Swedish prison, is an interesting glimpse at the Cash show on the road. Dispensing with the typical greatest hits, the band opens with a very solid new song, “Orleans Parish Prison,” followed by a terrific Cash composition, “Jacob Green,” about a young man arrested for drug possession who commits suicide after being brutalized by the system. (Years later, “Jacob Green” would find new life on the Murder chapter of Cash’s Love, God, Murder trilogy of themed compilations, released by Legacy/Columbia in 2000.) The live album also finds Cash and company putting the Tennessee Three stamp on another pair of sterling Kristofferson classics, “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” along with taking a tasty run through “The Prisoners Song” and a crazed version of Cash’s own “City Jail.” All and all, Pa Osteraker is a well played, well recorded, very fresh live disc only a legend of Cash’s stature could release on a major label. It’s a shame it’s taken so long for it to be re-released in the digital age, but better late than never.

Pa Osteraker, a 1973 album recorded live in a Swedish prison, is an interesting glimpse at the Cash show on the road. Dispensing with the typical greatest hits, the band opens with a very solid new song, “Orleans Parish Prison,” followed by a terrific Cash composition, “Jacob Green,” about a young man arrested for drug possession who commits suicide after being brutalized by the system. (Years later, “Jacob Green” would find new life on the Murder chapter of Cash’s Love, God, Murder trilogy of themed compilations, released by Legacy/Columbia in 2000.) The live album also finds Cash and company putting the Tennessee Three stamp on another pair of sterling Kristofferson classics, “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” along with taking a tasty run through “The Prisoners Song” and a crazed version of Cash’s own “City Jail.” All and all, Pa Osteraker is a well played, well recorded, very fresh live disc only a legend of Cash’s stature could release on a major label. It’s a shame it’s taken so long for it to be re-released in the digital age, but better late than never.

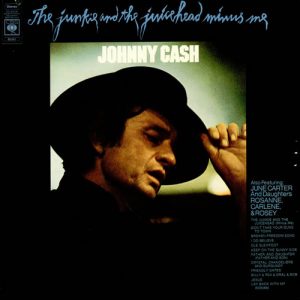

The year 1974 was a good one for Cash. His first release of the year was Ragged Old Flag, a set of self-composed songs recorded with his band and friends like Earl Scruggs. Most of the album is understated, comprised of songs that kind of resemble songs written by Kristofferson or Billy Joe Shaver in a round-about circle of inspiration. The title track is an over-the-top recitation full of informed and inspired patriotism, though the real highlight is “Southern Comfort,” about a tobacco farmer abandoned by his marijuana-growing woman. Although it didn’t feature any notable hits, Ragged Old Flag has been available on CD for a number of years; Cash’s other excellent release for ’74, though, makes its first appearance on CD in the Columbia box set.  The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me kicks off with the Kristofferson-penned title track, then moves into a funky re-working of “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” with some killer Carl Perkins guitar work. The album also offers the listeners the surprise of a teenage Rosanne Cash taking the lead vocal on another Kristofferson tune, “Broken Song of Freedom.” It’s a stunning track: a little flat in places, maybe, but full of youthful innocense. Rosanne isn’t the only family member with a cameo on the album, either; June does a sugary take on Johnny Horton’s “Old Slew Foot,” and she and Cash lay down an authoritative “Keep on the Sunny Side” before June’s daughter Rosie Nix joins her step dad for a duet on Cat Stevens‘ “Father and Daughter (Son).” As with Rosanne’s turn at the mic, Rosie’s performance is amateruish but undeniably soulful and real; especially in light of her troubled, short life of addiction and pain, it’s a genuinely moving glipse at a mysterious soul. Cash takes the lead on “Chrystal Chandeliers and Burgundy,” a really cool “Gentle on My Mind” type song written by Jack Routh, who also contributes “Friendly Gates” — a song sung on the album by his wife at the time, Carlene Carter. The all-in-the-family vibe carries over to the back cover, which featres great photos of June and all three girls looking just like characters from the Jodie Foster/Cherie Currie 1980 bad girl movie, Foxes. But despite featuring some of the first recordings of two future country superstars, The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me appears to have barely charted and disappeared without a trace.

The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me kicks off with the Kristofferson-penned title track, then moves into a funky re-working of “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” with some killer Carl Perkins guitar work. The album also offers the listeners the surprise of a teenage Rosanne Cash taking the lead vocal on another Kristofferson tune, “Broken Song of Freedom.” It’s a stunning track: a little flat in places, maybe, but full of youthful innocense. Rosanne isn’t the only family member with a cameo on the album, either; June does a sugary take on Johnny Horton’s “Old Slew Foot,” and she and Cash lay down an authoritative “Keep on the Sunny Side” before June’s daughter Rosie Nix joins her step dad for a duet on Cat Stevens‘ “Father and Daughter (Son).” As with Rosanne’s turn at the mic, Rosie’s performance is amateruish but undeniably soulful and real; especially in light of her troubled, short life of addiction and pain, it’s a genuinely moving glipse at a mysterious soul. Cash takes the lead on “Chrystal Chandeliers and Burgundy,” a really cool “Gentle on My Mind” type song written by Jack Routh, who also contributes “Friendly Gates” — a song sung on the album by his wife at the time, Carlene Carter. The all-in-the-family vibe carries over to the back cover, which featres great photos of June and all three girls looking just like characters from the Jodie Foster/Cherie Currie 1980 bad girl movie, Foxes. But despite featuring some of the first recordings of two future country superstars, The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me appears to have barely charted and disappeared without a trace.

As Cash took the opportunity to boost his talented family, a cast of recurring characters began making regular appearances in his work. Carl Perkins, long-time friend and fellow Sun Records veteran, contributed guitar excellence and songs, the Statler Brothers lent their vocals to gospel choruses, and Kristofferson penned hits. The aforementioned son-in-law Jack Routh also continued to be a formidable contributor; his “Hard Times Comin’” is a high point of 1975’s John R. Cash, alongside Billy Joe Shaver’s “Jesus was Our Savior (Cotton was Our King)” and Robbie Robertson’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” The album is the first of four records Cash made at Columbia that does not feature the sound of the Tennessee Three, making it an easy target for criticism from some fans. But the change was also somewhat of a nice and refreshing detour, allowing Cash to exercise his vocals at their peak on material he otherwise might not have attempted. Look at Them Beans (1975) follows suit with bassist Joe Allen and drummer Jerry Carrigan anchoring the rhythm section; it’s another decent effort with Cash in fine vocal form, with “Texas 1957” — the first of many Guy Clark numbers he would come to record — proving a real standout.

Strawberry Cake, from 1976, is another live album, this one recorded in London. Although the setlist features some redundant material from the better-known prison albums, it’s noteworthy for including a pair of somewhat strange and interesting new Cash originals — “Strawberry Cake” and “Destination Victoria Station” — as well as for the IRA bomb threat that interrupts the show right in the middle of June Carter’s spotlight on “Church in the Wildwood.” (Fortunately, she gets to start over after the theater is deemed safe for the audience and band to return.) Also released in 1976 was One Piece at a Time, which jumps out with the novelty title tune (a big hit single) and splits the tracks with studio guys and the Tennessee Three.

The Last Gunfighter Ballad (1977) brings the Tennessee Three sound back in full; this is yet another under-heard album, lost in the vast catalog despite offering a Guy Clark-penned title track that seems tailor-made for Cash’s voice. The same year’s The Rambler is an odd concept/mini-drama album that makes much use of the talented Cash clan, with Jack Routh, Rosanne Cash and Carlene Carter all performing as characters in the dialogue that plays between songs. I Would Like To See You Again (1978) stands out with two terrific duets with Waylon Jennings, “I Wish I Was Crazy Again” and “Ain’t No Good Chain Gang,” the later featuring a superb Jennings guitar solo over the classic Tennessee Three train beat.

The next three Cash albums make use of several more talented sons-in-law. Gone Girl (1978) caps a heaping helping of stomping rockabilly (including a rapid fire take on the Rolling Stones’ “No Expectations”) with a lovely take on Rodney Crowell’s “Song For the Life” with Crowell’s bride Rosanne singing along. (The album also features Cash’s version of Don Schlitz’ “The Gambler,” the same song Kenny Rogers would soon take to the top of the charts.) Silver (1979), marking Cash’s 25th year in the business, features Crowell’s slinky “Bullrider” alongside the top-5 hit “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” Billy Joe Shaver’s “Lately I Been Leaning Towards the Blues,” and a devious new take on the old “Cocaine Blues.” 1980’s Rockabilly Blues features Nick Lowe, then married to Carlene Carter, producing a version of his own “Without Love.” Marty Stuart, married to Cindy Cash, and Eddy Shaver, on-and-off-again boyfriend to Rosie Nix, make appearances on mandolin and guitar, insuring the instrumental work is top notch. All three of these albums are hard-driving, solid works worth seeking out; fortunately, all three are available as legal downloads (though Gone Girl makes its first appearance on CD in the Columbia box set.)

Coming after that decade-closing trifecta, 1981’s The Baron was a bit of a letdown. While the opening title track is a moving and quality piece of music, the rest of the album is much less successful, matching Cash’s less-than-inspired vocals with Billy Sherrill’s clean production. As if to offset that drift toward Nashville easy listening, Cash’s next release, 1982’s The Survivors, reunited him with Sun Records pals Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins for a live album produced by Crowell and utilizing Stuart’s picking. Recorded in West Germany, the set features excellent takes on “I Forgot to Remember to Forget” and “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad.” The same year’s The Adventures of Johnny Cash has a terrible cover photo but keeps up the drive with Shaver’s “Georgia on a Fast Train” and Merle Haggard’s “Good Old American Guest.”

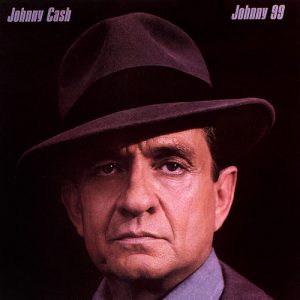

Coming after that decade-closing trifecta, 1981’s The Baron was a bit of a letdown. While the opening title track is a moving and quality piece of music, the rest of the album is much less successful, matching Cash’s less-than-inspired vocals with Billy Sherrill’s clean production. As if to offset that drift toward Nashville easy listening, Cash’s next release, 1982’s The Survivors, reunited him with Sun Records pals Jerry Lee Lewis and Carl Perkins for a live album produced by Crowell and utilizing Stuart’s picking. Recorded in West Germany, the set features excellent takes on “I Forgot to Remember to Forget” and “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad.” The same year’s The Adventures of Johnny Cash has a terrible cover photo but keeps up the drive with Shaver’s “Georgia on a Fast Train” and Merle Haggard’s “Good Old American Guest.”  The best album from this whole phase of Cash’s career, though, may well be 1983’s Johnny 99. Two Bruce Springsteen covers from the undeniably Cash-inspired Nebraska album (“Highway Patrolman” and “Johnny 99”), along with a stomping take on Guy Clark’s “New Cut Road,” Eric Von Shmidt’s “Joshua Gone Barbados” and Mack Vickery’s informed and not clichéd “God Bless Robert E. Lee” all add up to a record of top-notch material sung and played with authority and conviction.

The best album from this whole phase of Cash’s career, though, may well be 1983’s Johnny 99. Two Bruce Springsteen covers from the undeniably Cash-inspired Nebraska album (“Highway Patrolman” and “Johnny 99”), along with a stomping take on Guy Clark’s “New Cut Road,” Eric Von Shmidt’s “Joshua Gone Barbados” and Mack Vickery’s informed and not clichéd “God Bless Robert E. Lee” all add up to a record of top-notch material sung and played with authority and conviction.

Unfortunately, Johnny 99 would be the last of the Cash sound to grace a proper Columbia studio recording. A live album cut in Prague five years earlier (Koncert V Praze — In Prague Live) would see release in 1983, then it would be two more years before Cash delivered the Chips Moman-produced Rainbow. In theory, that one shoulda been a contender. Moman was already a legendary figure in the Memphis music world, having overseen classic albums by Dusty Springfield, Elvis Presley, BJ Thomas and hundreds more. In the mid-70s, he produced Waylon Jenning’s hugely successful Ol’ Waylon album and had more recently hit with Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard’s Pancho and Lefty. But despite taking a shot at some quality material like John Fogerty’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” and Kristofferson’s “Casey’s Last Ride,” Rainbow is arguably one of the least essential albums of Cash’s lengthly Columbia era due to Moman’s atmospheric soundscapes and Cash’s lackluster vocals. The one real highlight is “Here Comes that Rainbow Again,” a nice nod to Steinbeck written by Kristofferson with Waylon singing harmonies.

The Cash/Moman team would remain intact for the rest of Cash’s tenure on Columbia. After performing a Christmas special in Switzerland, Cash and constant associates Jennings and Kristofferson teamed with Willie Nelson to record as the Highwaymen. At this juncture in their careers all four were able to raise their profiles considerably by banding together. Unfortunately, super group teamings don’t always lead to super music. While Highwayman’s namesake hit single, composed by Jimmy Webb, is an undeniably great radio song, tugging at heart sleeves with the vocal trade offs, the rest of the 1985 album is a little false sounding and schlocky. If there is a Cash song on there you like, chances are you can find it elsewhere in the Man in Black’s catalog in a much superior form. In 1986, Cash and Jennings left Nelson and Kristofferson to their own devices to record a somewhat more satisfying duo album titled Heroes. The record is full of well-chosen material and the vocal blend between the two baritones is consistently pleasing. But on the downside, coming at a time when acts like Jason and the Scorchers, the Georgia Satelites, Steve Earle and more were drawing young people to country-based music with roots-rocking attitude and edge, these two much-older heroes decided to play it very safe and mellow.

Shortly after the release of Heroes, Cash was released from Columbia. At Mercury Records he would cut a few albums to little enthusiasm and fanfare, returning to the old homestead for another Highwaymen record (Highwayman 2) in 1990 that is the equal of the first in most ways. Following his career resurrection later in the decade with Rick Rubin’s American Records, Columbia would reach into the vaults in 2000 for another live album, recorded in 1969 at Madison Square Garden, containing the same lineup and much of the same material as the other live discs from that era along with a little more religious material and later ’60s hits “Five Feet High and Rising” and “Johnny Yuma.”

At Madison Square Garden completes the run of original releases in The Complete Columbia Album Collection, but the box set is rounded out with three noteworthy bonus discs: Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar, and the two-disc Singles, Plus. The former is an unexpected but essential bonus, comprising not only all 12 tracks from Cash’s 1957 debut full-length on Sun of the same name, but a generous selection of his other recordings for the label before his move to Columbia. The 56 songs collected on Singles, Plus include a plethora of non-LP singles (like “What Is Truth” and “Rosanna’s Going Wild”), Cash cameos on tracks recorded on Columbia records by Bob Dylan and the Earl Scruggs Review, and a number of other obscure tunes that sank without much notice.

At Madison Square Garden completes the run of original releases in The Complete Columbia Album Collection, but the box set is rounded out with three noteworthy bonus discs: Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar, and the two-disc Singles, Plus. The former is an unexpected but essential bonus, comprising not only all 12 tracks from Cash’s 1957 debut full-length on Sun of the same name, but a generous selection of his other recordings for the label before his move to Columbia. The 56 songs collected on Singles, Plus include a plethora of non-LP singles (like “What Is Truth” and “Rosanna’s Going Wild”), Cash cameos on tracks recorded on Columbia records by Bob Dylan and the Earl Scruggs Review, and a number of other obscure tunes that sank without much notice.

Over the years, Cash’s music has been collected in many forms: double-disc reissues, box sets, greatest hits, theme records. But this is the first package that takes away any argument about what should and shouldn’t be here, as it is all here (bar, of course, his short stint on Mercury and victory lap with American Recordings.) Casual fans will still be better served by compilations and a few key titles available a la carte, and even some diehards might balk at the box set’s hefty price — this much Cash in one package doesn’t cost pocket change — and opt to continue filling out their collection the old-fashioned way, one piece at a time. But for those with the means and/or inclination to splurge, The Complete Columbia Album Collection yields treasures in spades. One wishes that the accompanying essay offered a little more historical and anecdotal details about each release, but the credits are listed in full and every album is presented in its own sleeve replicating the original LP artwork (right down to the gatefold format for some titles). The discs are also discreetly but clearly numbered in chronological order, and neatly tucked into a heavy duty, centerpiece-worthy attractive box. But of course, the biggest value of the collection is the music itself — especially the volume of cast-aside nuggets that have languished for far too long in forgotten obscurity. Johnny Cash is the type of artist whose depth demands closer inspection, and having all these missing pieces in one place alongside the work we’ve long known and loved is much more than a mere bounty for completist fans. It’s a monument of American musical history — and a testament to what was possible in a bygone era when chances were taken and loyalty prevailed, even when those chances proved to be far ahead of their time.

No Comment