By Eric Hisaw

(LSM May/June 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 3)

“Well I left my home out on the great high plains, headed for some new terrain …”

With the opening line of his 1977 self-titled solo debut, Joe Ely announced where he was coming from and what his intentions were. The high, lonesome West Texas plains, and that restless urge to travel, both spiritually and physically, have informed nearly every note of the Amarillo-born, Lubbock-reared songwriter’s nearly four-decade recording career (going all the way back to the 1972 debut by the Flatlanders). In all that time, he’s never had a single bona fide breakout “hit” to speak of, and yet few other artists can claim a comparable consistency of relevance and intensity over multiple decades that Ely’s extensive catalog has shown. Peer respect and pockets of cult hero devotion could lead one to believe Ely was in the same club as superstars like Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty, though his own career path has been closer to fellow free spirits Steve Earle and Dave Alvin. If the lucky brakes that lead to mass acceptance have eluded him, Ely has still found enough of an audience of true believers to carry on undaunted.

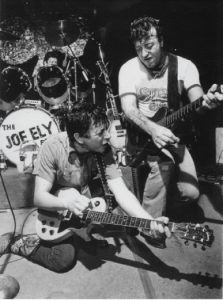

Lloyd Maines, the pedal-steel guitar master who’s contributed to every phase and ensemble in Ely’s solo career, calls him “the rock ’n’ roll Bob Wills.” It’s a nod to Ely’s fearless selflessness as a bandleader, always allowing his musicians to stretch out and shine. As a result, Ely’s extensive body of work — all but impossible to digest in one sitting — can conveniently be broken down into more manageable eras, each defined as much by the sidemen and bands he’s worked with over the years as by the different directions he’s explored with his songwriting. But through it all, Ely’s own personality and artistic prowess remains the defining component. For years, diehard fans and critics alike have waged debates over the matter of one era or other being “better” than the rest, or one guitarist’s style somehow being more appropriate to Ely’s music than any others. But Maines is quick to point out that there never was any great fracturing in the ranks. “Everyone who ever worked with Joe would jump at the chance to play with him again,” Maines insists. “One thing about Joe Ely — and I’ve played every kind of gig with him, from little clubs to opening for the Rolling Stones — I’ve never seen him give less than 110-percent at any show.”

That same guarantee of both quality and intensity applies just as much to Ely’s extensive catalog of both studio and live albums. No matter where you drop the needle, no matter what year or lineup, you’re not going to find a false note.

Phase One: The “Original” Joe Ely Band and MCA “Round One”

Boasting the twin bang and twang of guitarist Jesse Taylor and Maines on steel, the first Joe Ely Band came out the gate with all pistons firing. The 1977 debut, Joe Ely, rolls and rocks through 10 original songs with a rakish lyrical edge and an ultra-confident delivery, maintaining a reverence for the band’s hard-country roots while sounding unlike anything else. Fellow Lubbock songwriters Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore — Ely’s chief cohorts in the once-and-future Flatlanders — contribute some stellar songs to match up with Ely’s own energetic honky-tonk beat poems. “If You Were a Bluebird,” “Treat Me Like a Saturday Night” and “She Never Spoke Spanish to Me” have all become standards, done so many times it’s easy to lose sight of where they came from. Here are the original versions in all their glory with stunning arrangements and intros. The band found a sympathetic producer in Nashville guitar slinger Chip Young, whose success with Delbert McClinton and Billy Swan made him possibly the best man in Music City for the job.

Boasting the twin bang and twang of guitarist Jesse Taylor and Maines on steel, the first Joe Ely Band came out the gate with all pistons firing. The 1977 debut, Joe Ely, rolls and rocks through 10 original songs with a rakish lyrical edge and an ultra-confident delivery, maintaining a reverence for the band’s hard-country roots while sounding unlike anything else. Fellow Lubbock songwriters Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore — Ely’s chief cohorts in the once-and-future Flatlanders — contribute some stellar songs to match up with Ely’s own energetic honky-tonk beat poems. “If You Were a Bluebird,” “Treat Me Like a Saturday Night” and “She Never Spoke Spanish to Me” have all become standards, done so many times it’s easy to lose sight of where they came from. Here are the original versions in all their glory with stunning arrangements and intros. The band found a sympathetic producer in Nashville guitar slinger Chip Young, whose success with Delbert McClinton and Billy Swan made him possibly the best man in Music City for the job.  The follow-up, 1978’s Honky Tonk Masquerade, picks up right where the debut left off. More acoustic oriented with fewer dueling solos, it boasts even stronger material and the fulltime addition of accordionist Ponty Bone. Hancock’s “Boxcars,” Gilmore’s “Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown” and Ely’s own “Fingernails” add to his repertoire’s growing list of instant classics. So do the title track, which is very much in the vein of Jerry Lee Lewis’ great country records, and “Because of the Wind,” a standard bearer of pedal-steel guitar beauty.

The follow-up, 1978’s Honky Tonk Masquerade, picks up right where the debut left off. More acoustic oriented with fewer dueling solos, it boasts even stronger material and the fulltime addition of accordionist Ponty Bone. Hancock’s “Boxcars,” Gilmore’s “Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown” and Ely’s own “Fingernails” add to his repertoire’s growing list of instant classics. So do the title track, which is very much in the vein of Jerry Lee Lewis’ great country records, and “Because of the Wind,” a standard bearer of pedal-steel guitar beauty.

For the third album, the band, augmented by sax man Ed Vizard and fiddler Richard Bowden, moved away from Young’s log-cabin studio to work with legendary producer Bob Johnston, whose credits include iconic albums by Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan, in Seattle, Wash. Johnston’s eccentric nature took the band by surprise; to Ponty Bone, he seemed more interested in sketching mostly unflattering caricatures of the band members, while Maines recalls the producer spending precious recording time decorating the studio to look like it was New Year’s Eve.  The resulting album, 1979’s Down on the Drag, was a disappointment to the band, with both Ely and Maines bemoaning what they considered a lack of energy and muddy mix. As far as this listener is concerned, though, I can only wonder … what the hell are they talking about? A series of excellent, often dark songs featuring masterful instrumental interplay and a throwing-caution-to-the-wind attitude make this one of my favorites. Hancock once again contributes a couple of his best songs, with the title track and “Fools Fall In Love,” while Vizard’s soulful “BBQ and Foam” features one of Taylor’s grittiest guitar leads.

The resulting album, 1979’s Down on the Drag, was a disappointment to the band, with both Ely and Maines bemoaning what they considered a lack of energy and muddy mix. As far as this listener is concerned, though, I can only wonder … what the hell are they talking about? A series of excellent, often dark songs featuring masterful instrumental interplay and a throwing-caution-to-the-wind attitude make this one of my favorites. Hancock once again contributes a couple of his best songs, with the title track and “Fools Fall In Love,” while Vizard’s soulful “BBQ and Foam” features one of Taylor’s grittiest guitar leads.

In the U.S., where they were originally promoted as a country act, the band had yet to grab a foothold on the live circuit. “Our booking agent would book us at these old county fairs and pig races in the Appalachian Mountains, and when we’d play, Lloyd would hit that stomp box and turn his steel into a flaming war machine, and people would just leave in droves,” Ely remembers. Overseas it was a totally different story. The Ely Band’s British shows bore a mighty legend. Recorded while touring with like-minded genre-bending populist rockers the Clash, 1980’s Live Shots captures the crew, with new drummer Robert Marquand and keyboardist Reese Wynans, at their absolute rip-roaring finest. A nod to Lubbock icon Buddy Holly with the R’n’B classic “Midnight Shift” and Ely’s revamping of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Long Snake Moan” show off the band’s range of material. If there is one slab of wax that sums up the spirit and guts of the original group, this is it.

In the U.S., where they were originally promoted as a country act, the band had yet to grab a foothold on the live circuit. “Our booking agent would book us at these old county fairs and pig races in the Appalachian Mountains, and when we’d play, Lloyd would hit that stomp box and turn his steel into a flaming war machine, and people would just leave in droves,” Ely remembers. Overseas it was a totally different story. The Ely Band’s British shows bore a mighty legend. Recorded while touring with like-minded genre-bending populist rockers the Clash, 1980’s Live Shots captures the crew, with new drummer Robert Marquand and keyboardist Reese Wynans, at their absolute rip-roaring finest. A nod to Lubbock icon Buddy Holly with the R’n’B classic “Midnight Shift” and Ely’s revamping of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Long Snake Moan” show off the band’s range of material. If there is one slab of wax that sums up the spirit and guts of the original group, this is it.

For 1981’s Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, rockabilly fever had pushed out any and all folk leanings. The guitar team hits its zenith on the title track, with Maines’ screaming siren pedal steel going toe to toe with Taylor’s rapid fire Chuck-Berry-on-steroids guitar breaks. The rest of the LP keeps up the drive. Gilmore’s classic “Dallas” is muscled up with a Fabulous Thunderbirds-style shuffle and some Western-swing inspired twin guitar lines. And David Halley’s “Hard Living” and Hancock’s “Road Hawg” are the kind of songs that still drive Ely’s live audiences wild.

For 1981’s Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, rockabilly fever had pushed out any and all folk leanings. The guitar team hits its zenith on the title track, with Maines’ screaming siren pedal steel going toe to toe with Taylor’s rapid fire Chuck-Berry-on-steroids guitar breaks. The rest of the LP keeps up the drive. Gilmore’s classic “Dallas” is muscled up with a Fabulous Thunderbirds-style shuffle and some Western-swing inspired twin guitar lines. And David Halley’s “Hard Living” and Hancock’s “Road Hawg” are the kind of songs that still drive Ely’s live audiences wild.

Phase Two: The Hi Res Experiment

After five solid years of pushing honky-tonkin’ rock ’n’ roll to its far limits, the original band drifted apart. Maines left the road to raise a family, Taylor quit to pursue his own blues/rock muse, and Ponty Bone formed the Squeezetones. Ely’s own interest in computers and the idea of making music in the comforts of his new home studio led to the most misunderstood and ill-received album of his career: 1984’s Hi Res.  Although Ely did originally record the entire album — reportedly conceived as a soundtrack to a long-form video about a cowboy hobo transported into the digital age — at home with guitarist Mitch Watkins, a primitive synthesizer and an Apple II computer, that version has never been heard by the public. That’s because MCA insisted on having it re-recorded with a full band in a professional studio in Los Angeles. The end result still maintains a futuristic rockabilly/New-Wave style, with bleeping synthesizers, programmed percussion and Roscoe Beck’s snappy bass. If that just seems all wrong, the record does have a dreamy cinematic appeal, and also features a few tunes like “Cool Rockin’ Loretta” and “What’s Shakin’ Tonight” that are still live staples. It also has an interesting first crack at “Letter to Laredo” that’s very different from the flamenco-style version Ely would record 11 years later.

Although Ely did originally record the entire album — reportedly conceived as a soundtrack to a long-form video about a cowboy hobo transported into the digital age — at home with guitarist Mitch Watkins, a primitive synthesizer and an Apple II computer, that version has never been heard by the public. That’s because MCA insisted on having it re-recorded with a full band in a professional studio in Los Angeles. The end result still maintains a futuristic rockabilly/New-Wave style, with bleeping synthesizers, programmed percussion and Roscoe Beck’s snappy bass. If that just seems all wrong, the record does have a dreamy cinematic appeal, and also features a few tunes like “Cool Rockin’ Loretta” and “What’s Shakin’ Tonight” that are still live staples. It also has an interesting first crack at “Letter to Laredo” that’s very different from the flamenco-style version Ely would record 11 years later.

Although Hi Res sounds good now, with the perspective of hindsight, it’s easy to see why it was perceived as such a travesty upon its original release 28 years ago: fans and critics eagerly anticipating the “new Joe Ely album” had to have been caught off guard by not only the new sounds, but the absence of the strong personalities that were so key to the original band. Hi-Res is the only one of Ely’s albums that was never re-released domestically on CD, though a pricey import version (which pairs it with Musta Notta Gotta Lotta on a single disc) popped up a couple of years ago. If you can find it — or an original copy on vinyl — give it a chance. Or, you could just wait for Ely to make good on his promise to finally release his preferred original “low-res” version in the near future.

Phase Three: Hightone Boogie

Hi Res marked the end of Ely’s first run on MCA. Three years later, he came storming back on a new label (the independent, roots-music stable Hightone Records) with a brand new band of high-octane roadhouse rockers. Though nothing like the original lineup that blew out of Lubbock in the ’70s, the Joe Ely Band of the mid-to-late ’80s proved very formidable in its own right, with Jimmy Pettit and Davis McClarty forming a pounding rhythmic foundation for virtuoso guitarist David Grissom to lay down some serious Hendrix-inspired solos. On 1987’s Lord of the Highway, abetted by Rolling Stones saxophonist Bobby Keys, they put together an impressive set of loud guitar rock and soul. Do “My Baby Thinks She’s French” and “Everybody Got Hammered” have the same poetic intensity that the earlier material had? Well, no … but the album still boasts a ton of rock ’n’ roll energy, and “Row of Dominoes” is as fine a song as Butch Hancock has ever contributed to any Ely album. “Me and Billy the Kid,” arguably Ely’s most covered song, makes its debut here, as does the Grissom showpiece, “Letter To L.A.”

Hi Res marked the end of Ely’s first run on MCA. Three years later, he came storming back on a new label (the independent, roots-music stable Hightone Records) with a brand new band of high-octane roadhouse rockers. Though nothing like the original lineup that blew out of Lubbock in the ’70s, the Joe Ely Band of the mid-to-late ’80s proved very formidable in its own right, with Jimmy Pettit and Davis McClarty forming a pounding rhythmic foundation for virtuoso guitarist David Grissom to lay down some serious Hendrix-inspired solos. On 1987’s Lord of the Highway, abetted by Rolling Stones saxophonist Bobby Keys, they put together an impressive set of loud guitar rock and soul. Do “My Baby Thinks She’s French” and “Everybody Got Hammered” have the same poetic intensity that the earlier material had? Well, no … but the album still boasts a ton of rock ’n’ roll energy, and “Row of Dominoes” is as fine a song as Butch Hancock has ever contributed to any Ely album. “Me and Billy the Kid,” arguably Ely’s most covered song, makes its debut here, as does the Grissom showpiece, “Letter To L.A.”

The following year’s Dig All Night covers similar territory, opening with the crash and bang of “Settle For Love” and featuring longtime Ely standards “My Eyes Got Lucky” and “Maybe She’ll Find Me.” A strong record throughout, this is when the band reached its height of popularity in Austin, nearly sweeping the 1988 Austin Music Awards. Striking while the iron was hot, Ely recorded two shows with the band at Austin’s late, lamented Liberty Lunch nightclub. The resulting Live At Liberty Lunch, released in 1990 and graced with photographer Cindy Light’s iconic cover shot, captures the second classic band at its rocking best. Songs from across Ely’s entire catalog are given the Grissom guitar-hero treatment, and the cover of R.C. Banks “Where Is My Love” is worth the admission on its own.

The following year’s Dig All Night covers similar territory, opening with the crash and bang of “Settle For Love” and featuring longtime Ely standards “My Eyes Got Lucky” and “Maybe She’ll Find Me.” A strong record throughout, this is when the band reached its height of popularity in Austin, nearly sweeping the 1988 Austin Music Awards. Striking while the iron was hot, Ely recorded two shows with the band at Austin’s late, lamented Liberty Lunch nightclub. The resulting Live At Liberty Lunch, released in 1990 and graced with photographer Cindy Light’s iconic cover shot, captures the second classic band at its rocking best. Songs from across Ely’s entire catalog are given the Grissom guitar-hero treatment, and the cover of R.C. Banks “Where Is My Love” is worth the admission on its own.  Another live record from this era, Live in Chicago 1987, retrieved from the vaults and released in 2008 on Ely’s own Rack ’Em Records, presents a similar but slightly different picture of the combo. Pettit and McLarty drive the rhythm like their lives depend on it, and Ely is forever the frontman with energy and charisma to burn.

Another live record from this era, Live in Chicago 1987, retrieved from the vaults and released in 2008 on Ely’s own Rack ’Em Records, presents a similar but slightly different picture of the combo. Pettit and McLarty drive the rhythm like their lives depend on it, and Ely is forever the frontman with energy and charisma to burn.  But the “it factor” on this set is Bobby Keys, who toured with the band in support of Lord of the Highway but had returned to his other gig with the Stones by the time Live at Liberty Lunch was recorded. To this listener, Grissom is at his best when tempered by another soloist, and with Keys onboard the two make a powerful team, handing off solos in a manner reminiscent of Taylor and Maines in the original band. This recording, more or less an authorized bootleg, doesn’t have the high fidelity of the Liberty Lunch set and the tape seems to have been sped up, but those are small complaints considering the many magic moments on display.

But the “it factor” on this set is Bobby Keys, who toured with the band in support of Lord of the Highway but had returned to his other gig with the Stones by the time Live at Liberty Lunch was recorded. To this listener, Grissom is at his best when tempered by another soloist, and with Keys onboard the two make a powerful team, handing off solos in a manner reminiscent of Taylor and Maines in the original band. This recording, more or less an authorized bootleg, doesn’t have the high fidelity of the Liberty Lunch set and the tape seems to have been sped up, but those are small complaints considering the many magic moments on display.

Phase Four: MCA “Round Two” & the Flamenco Years

MCA came back into the picture after Steve Earle turned label honcho Tony Brown onto Ely’s new sound. “He played me Lord of the Highway from Calgary to Banff, doing 80 miles an hour, me watching for the Mounted Police and him playin’ this, screamin’ in my ear and singing the songs,” Brown told the Los Angeles Times. “He played that album wide open, there and back. I remember it like it was yesterday.” Brown signed Ely to MCA Nashville just in time to release the already recorded Live at Liberty Lunch, which Hightone had inexplicably passed on. He then co-produced the next studio album, 1992’s Love and Danger, which remains by far the most commercially accessible record of Ely’s career. Although the core band from the ’80s is featured on most of the album, the powerhouse sound of the two Hightone releases and Live at Liberty Lunch is cleaned up here with beds of acoustic guitar, B3 organ, and back-up vocals courtesy of Nashville harmony queens Jonell Mosser and Ashley Cleveland. As far as the songs go, it’s a solid set, with killer covers of Dave Alvin’s “Every Night About This Time” and Robert Earl Keen’s “Whenever Kindness Fails” and the love-it-or-hate-it “The Road Goes On Forever” sitting next to enduring Ely originals like “Slow You Down” and a reworked “Settle for Love.” But production-wise, it just sounds atypically sanitized — at least by Ely standards. Brown, having previously accomplished the improbable feat of fitting Earle’s ragged vision into mainstream country music (via the smash Guitar Town), was perhaps a little too over-confident in feeling like he could repeat that success with Ely. As a result, Love and Danger, though by no means a bad record, remains my personal least recommended place to start.

MCA came back into the picture after Steve Earle turned label honcho Tony Brown onto Ely’s new sound. “He played me Lord of the Highway from Calgary to Banff, doing 80 miles an hour, me watching for the Mounted Police and him playin’ this, screamin’ in my ear and singing the songs,” Brown told the Los Angeles Times. “He played that album wide open, there and back. I remember it like it was yesterday.” Brown signed Ely to MCA Nashville just in time to release the already recorded Live at Liberty Lunch, which Hightone had inexplicably passed on. He then co-produced the next studio album, 1992’s Love and Danger, which remains by far the most commercially accessible record of Ely’s career. Although the core band from the ’80s is featured on most of the album, the powerhouse sound of the two Hightone releases and Live at Liberty Lunch is cleaned up here with beds of acoustic guitar, B3 organ, and back-up vocals courtesy of Nashville harmony queens Jonell Mosser and Ashley Cleveland. As far as the songs go, it’s a solid set, with killer covers of Dave Alvin’s “Every Night About This Time” and Robert Earl Keen’s “Whenever Kindness Fails” and the love-it-or-hate-it “The Road Goes On Forever” sitting next to enduring Ely originals like “Slow You Down” and a reworked “Settle for Love.” But production-wise, it just sounds atypically sanitized — at least by Ely standards. Brown, having previously accomplished the improbable feat of fitting Earle’s ragged vision into mainstream country music (via the smash Guitar Town), was perhaps a little too over-confident in feeling like he could repeat that success with Ely. As a result, Love and Danger, though by no means a bad record, remains my personal least recommended place to start.

Shaking off the polish of the previous album (along with the last remnants of his four-piece rock combo), 1995’s Letter To Laredo found Ely chasing a somewhat more personal muse than the greasy roots rock he’d been banging out of late. The cruising-strip imagery and light-hearted boogie were replaced with flamenco guitars, accordions and lyrics inspired by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. The opening “All Just to Get to You,” a song Ely co-wrote with Will Sexton that actually made its debut on Sexton’s Ely-produced 1988 Will and the Kill album, is a classic travelogue in the name of love. Tom Russell’s epic “Gallo De Cielo” gets its definitive reading with flamenco guitarist Teye’s dramatic accompaniment. And Maines and Ponty Bone return to the Ely fold in impeccable form, providing slices of dobro and atmospheric accordion to the exotic mix of nylon-string guitar runs and thumping percussion. Ely stayed steadfastly in that border groove for 1998’s Twistin’ in the Wind, which was also something of a summit for Ely guitar luminaries past and present: the album features performances by not only Grissom, Teye and Maines, but also Watkins (from Hi Res) and Taylor.

Shaking off the polish of the previous album (along with the last remnants of his four-piece rock combo), 1995’s Letter To Laredo found Ely chasing a somewhat more personal muse than the greasy roots rock he’d been banging out of late. The cruising-strip imagery and light-hearted boogie were replaced with flamenco guitars, accordions and lyrics inspired by the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. The opening “All Just to Get to You,” a song Ely co-wrote with Will Sexton that actually made its debut on Sexton’s Ely-produced 1988 Will and the Kill album, is a classic travelogue in the name of love. Tom Russell’s epic “Gallo De Cielo” gets its definitive reading with flamenco guitarist Teye’s dramatic accompaniment. And Maines and Ponty Bone return to the Ely fold in impeccable form, providing slices of dobro and atmospheric accordion to the exotic mix of nylon-string guitar runs and thumping percussion. Ely stayed steadfastly in that border groove for 1998’s Twistin’ in the Wind, which was also something of a summit for Ely guitar luminaries past and present: the album features performances by not only Grissom, Teye and Maines, but also Watkins (from Hi Res) and Taylor.  The classic power of Taylor and Maines’ dueling instruments is re-established in thrilling fashion on the very first track, “Up On the Ridge.” Other high points on the album include “Working For the Man,” a great minor-key blues workout; “I Will Lose My Life,” a triplet-timed tip of the hat to Freddy Fender; and the anthemic title track, which makes the most of Taylor’s unique tone (not to mention the full emotional potency of Ely’s voice). Even “Nacho Mama,” despite its unpromising title, proves a keeper: it’s a groovy, Latin-tinged ode to girl power featuring some very cool accordion and Farfisa organ work.

The classic power of Taylor and Maines’ dueling instruments is re-established in thrilling fashion on the very first track, “Up On the Ridge.” Other high points on the album include “Working For the Man,” a great minor-key blues workout; “I Will Lose My Life,” a triplet-timed tip of the hat to Freddy Fender; and the anthemic title track, which makes the most of Taylor’s unique tone (not to mention the full emotional potency of Ely’s voice). Even “Nacho Mama,” despite its unpromising title, proves a keeper: it’s a groovy, Latin-tinged ode to girl power featuring some very cool accordion and Farfisa organ work.

If some Ely fans were left cold by the heavy drama and liberal use of Spanish guitar on these albums, 2000’s Live @ Antones, released on Rounder Records, won them back. Ely and his band — a veritable dream-team combo featuring Maines, Taylor, Teye and Ely on guitars, Joel Guzman on accordion, Rafael Gayol on drums and Gary Herman on bass — burn through songs from all stages of his career.  Taylor and Maines put their own stamp on Grissom-era favorites like “Me and Billy the Kid,” “My Eyes Got Lucky” and “Everybody Got Hammered.” Most impressive, though, are the live versions of the newer material from Laredo and Twistin’, where Taylor and Maines take their soloing to new heights. A run through Utah Philips’ bizarre “Rock Salt and Nails” is another highpoint, and the closing tribute to Buddy Holly, “Oh Boy,” is high-speed, West Texas rock ’n’ roll at it’s finest.

Taylor and Maines put their own stamp on Grissom-era favorites like “Me and Billy the Kid,” “My Eyes Got Lucky” and “Everybody Got Hammered.” Most impressive, though, are the live versions of the newer material from Laredo and Twistin’, where Taylor and Maines take their soloing to new heights. A run through Utah Philips’ bizarre “Rock Salt and Nails” is another highpoint, and the closing tribute to Buddy Holly, “Oh Boy,” is high-speed, West Texas rock ’n’ roll at it’s finest.

Phase Five: The Elder Statesman

By the early 2000s, after the Live @ Antones band drifted apart, Ely partnered with Hancock and Gilmore for what proved to be a very successful — and ongoing — reunion of the Flatlanders, picking up in a very different place than they’d left off from their humble beginnings as an old-timey hippie country band in the early-70s.  The Americana/folk scene has always been supportive of collaboration, and the group (and New West Records) found a solid niche with their first two new albums of the decade, 2002’s Now Again and 2004’s Wheels of Fortune. Ely himself capably produced both of those, but the Flatlanders’ third album of the decade was

The Americana/folk scene has always been supportive of collaboration, and the group (and New West Records) found a solid niche with their first two new albums of the decade, 2002’s Now Again and 2004’s Wheels of Fortune. Ely himself capably produced both of those, but the Flatlanders’ third album of the decade was  the real charm: 2009’s Maines-produced Hills and Valleys. The Ely-sung opener, “Homeland Refugee,” a modern tale of recession-era desperation, marked the trio’s most powerful track. In addition to the

the real charm: 2009’s Maines-produced Hills and Valleys. The Ely-sung opener, “Homeland Refugee,” a modern tale of recession-era desperation, marked the trio’s most powerful track. In addition to the  Flatlanders, Ely also found his way into the ranks of another super group, the mercurial Los Super Seven: first for the troupe’s Grammy-winning 1998 debut, Los Super Seven — on which Ely sang Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee” — and again on 2005’s Heard It On the X, covering fellow West Texan Bobby Fuller’s “Let Her Dance.”

Flatlanders, Ely also found his way into the ranks of another super group, the mercurial Los Super Seven: first for the troupe’s Grammy-winning 1998 debut, Los Super Seven — on which Ely sang Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee” — and again on 2005’s Heard It On the X, covering fellow West Texan Bobby Fuller’s “Let Her Dance.”

In the thick of all his ensemble work, Ely found time in 2003 to release a new album of his own, Streets of Sin, using ringers from the Flatlanders’ live band like guitarist Rob Gjersoe as well as Grissom and Guzman. Despite the familiar players, this was probably Ely’s most “solo” album like effort since Hi Res, with the sidemen taking a backseat to his compelling story telling. A solid record from top to bottom, it has some very memorable moments in “Twisty River Bridge,” “I Gotta Find Old Joe” and “All That You Need.” And “95 South,” with its Carl Perkins guitar riff and reference to “potholes bigger than craters on the moon,” is classic Ely travel music.

In the thick of all his ensemble work, Ely found time in 2003 to release a new album of his own, Streets of Sin, using ringers from the Flatlanders’ live band like guitarist Rob Gjersoe as well as Grissom and Guzman. Despite the familiar players, this was probably Ely’s most “solo” album like effort since Hi Res, with the sidemen taking a backseat to his compelling story telling. A solid record from top to bottom, it has some very memorable moments in “Twisty River Bridge,” “I Gotta Find Old Joe” and “All That You Need.” And “95 South,” with its Carl Perkins guitar riff and reference to “potholes bigger than craters on the moon,” is classic Ely travel music.

In 2007, Ely released a trio of works best understood as a whole. The book Bonfire of Roadmaps, the all-acoustic Silver City (Pearls from the Vault, Vol. 1), and the rocking Happy Songs From Rattlesnake Gulch were all trips down memory lane. The memoir, a collection of road journals in poem form, covered various tours and journeys around the world, scattered across many eras. Come to it looking for a definitive autobiography, and you’ll be both confused and disappointed; but approach it as a peek inside the private diary and free-form musings of a world-class drifter, and you’re in for a fascinating ride. The same goes for the book’s two companion albums, both issued on Ely’s own Rack ’Em Records and made up of songs from Ely’s deep archives that had been lost, found and reworked. Unencumbered by the pressure of newly written releases, both discs borrow heavily from familiar works — even twice repurposing the melody of “Me and Billy the Kid” (for “Drivin’ ’Cross Russia” on Silver City and “Miss Bonnie and Mister Clyde” on Happy Songs). The acoustic album is successful all around, showing off the voice and guitar that have made Ely a captivating solo performer.

In 2007, Ely released a trio of works best understood as a whole. The book Bonfire of Roadmaps, the all-acoustic Silver City (Pearls from the Vault, Vol. 1), and the rocking Happy Songs From Rattlesnake Gulch were all trips down memory lane. The memoir, a collection of road journals in poem form, covered various tours and journeys around the world, scattered across many eras. Come to it looking for a definitive autobiography, and you’ll be both confused and disappointed; but approach it as a peek inside the private diary and free-form musings of a world-class drifter, and you’re in for a fascinating ride. The same goes for the book’s two companion albums, both issued on Ely’s own Rack ’Em Records and made up of songs from Ely’s deep archives that had been lost, found and reworked. Unencumbered by the pressure of newly written releases, both discs borrow heavily from familiar works — even twice repurposing the melody of “Me and Billy the Kid” (for “Drivin’ ’Cross Russia” on Silver City and “Miss Bonnie and Mister Clyde” on Happy Songs). The acoustic album is successful all around, showing off the voice and guitar that have made Ely a captivating solo performer.  The electric album is mostly an excuse to groove — though that’s not a slight. Chock full of exciting guitar work and solid hooks, Happy Songs features two of Ely’s absolute finest moments on record. “Hard Luck Saint” is a tale about a Turkish immigrant who worked in Ely’s father’s used-clothing store when he was a kid, with half-time verses opening up into a Bobby Fuller-styled chorus. “Jesse Justice” pays tribute to a drifting pool shooter whose shady past and hotshot pool skills made a powerful impact on a young Ely. The lyrics flow along with a swampy beat reminiscent of Levon Helm and the Band and some tasty Muscle Shoals guitar licks.

The electric album is mostly an excuse to groove — though that’s not a slight. Chock full of exciting guitar work and solid hooks, Happy Songs features two of Ely’s absolute finest moments on record. “Hard Luck Saint” is a tale about a Turkish immigrant who worked in Ely’s father’s used-clothing store when he was a kid, with half-time verses opening up into a Bobby Fuller-styled chorus. “Jesse Justice” pays tribute to a drifting pool shooter whose shady past and hotshot pool skills made a powerful impact on a young Ely. The lyrics flow along with a swampy beat reminiscent of Levon Helm and the Band and some tasty Muscle Shoals guitar licks.

Multi-instrumentalist Joel Guzman has been Ely’s most consistent musical foil in the last decade. A veteran of Tejano legend Little Joe’s Familia, Guzman has lent his Chicano soul Hammond organ to great effect on many of Ely’s tracks. Live, Guzman is usually seen with a three-row button accordion. The pair’s duo shows are an amazing ride through the vast Ely catalog, featuring some deft finger-picked guitar work not always audible in the full-band context. At this stage, there are so many songs and eras to dip into, the material is given fresh life just by the context of the set list. In 2008, Ely self-released (again on Rack ’Em) a live album recorded at Austin’s Cactus Cafe. Digging back to Honky Tonk Masquerade for “Because of the Wind” and showing off “Miss Bonnie and Mister Clyde” from Happy Songs, the overall exquisite Live Cactus! takes a piece from every decade and direction.

Multi-instrumentalist Joel Guzman has been Ely’s most consistent musical foil in the last decade. A veteran of Tejano legend Little Joe’s Familia, Guzman has lent his Chicano soul Hammond organ to great effect on many of Ely’s tracks. Live, Guzman is usually seen with a three-row button accordion. The pair’s duo shows are an amazing ride through the vast Ely catalog, featuring some deft finger-picked guitar work not always audible in the full-band context. At this stage, there are so many songs and eras to dip into, the material is given fresh life just by the context of the set list. In 2008, Ely self-released (again on Rack ’Em) a live album recorded at Austin’s Cactus Cafe. Digging back to Honky Tonk Masquerade for “Because of the Wind” and showing off “Miss Bonnie and Mister Clyde” from Happy Songs, the overall exquisite Live Cactus! takes a piece from every decade and direction.

Legend has it that one night in New York City, shortly before embarking on the fateful Winter Dance Party, Buddy Holly crossed paths with Woody Guthrie in a New York pub. If any artist has encapsulated the potential of a meeting of those two minds, it would be the Joe Ely of the 21st century.  Satisfied At Last (2011, Rack ’Em) his first album of newly written material since launching his own label, features 10 Guthrie-esque story songs that drift through the southwestern landscape, riding a diverse set of rhythms it’s easy to imagine Holly strumming on his Stratocaster. “The Highway is My Home” gets things started with a bit of Latin funk that wouldn’t be out of place in kindred spirit Joe Strummer’s later day Mescaleros. The same goes for the reggae-tinged reworking of “Roll Again.” “You Can Bet I’m Gone” is a tip of the hat to Waylon Jennings’ two-beat groove with some outstanding guitar lines. Covering Billy Joe Shaver’s “Live Forever” is a little like taking on “Gimme Shelter” or “Let It Be,” but the always fearless troubadour pulls it off with flying colors, showing why the song has been a longtime fan favorite at his live shows. By the hypnotic closer, the Hancock-penned “Circumstance,” it’s apparent that 64-year-old Ely has lost little, if any, edge. Most impressive of all, though, is the fact that he is a stronger singer today then ever.

Satisfied At Last (2011, Rack ’Em) his first album of newly written material since launching his own label, features 10 Guthrie-esque story songs that drift through the southwestern landscape, riding a diverse set of rhythms it’s easy to imagine Holly strumming on his Stratocaster. “The Highway is My Home” gets things started with a bit of Latin funk that wouldn’t be out of place in kindred spirit Joe Strummer’s later day Mescaleros. The same goes for the reggae-tinged reworking of “Roll Again.” “You Can Bet I’m Gone” is a tip of the hat to Waylon Jennings’ two-beat groove with some outstanding guitar lines. Covering Billy Joe Shaver’s “Live Forever” is a little like taking on “Gimme Shelter” or “Let It Be,” but the always fearless troubadour pulls it off with flying colors, showing why the song has been a longtime fan favorite at his live shows. By the hypnotic closer, the Hancock-penned “Circumstance,” it’s apparent that 64-year-old Ely has lost little, if any, edge. Most impressive of all, though, is the fact that he is a stronger singer today then ever.

MR. RECORD MAN’S TOP 5 JOE ELY ALBUMS

Narrowing down a top five from the Joe Ely catalog is a daunting task; I’m naturally inclined to recommend them all. But after consulting with about a half dozen other diehard fans, here is my version of his most essential recordings.

1. Live Shots, MCA, 1980

A well-recorded document of one of the finest bands ever assembled, caught on a hot night in England. Ponty Bone’s Euro/Tex-Mex/Cajun accordion sets up some fiery guitar and pedal steel exchanges from Jesse Taylor and Lloyd Maines that manage to exceed the originals in spunk and attitude. Reese Wynans also pitches in with some tasty piano. Ely pours every ounce of heart and soul into the songs, making it easy to see what drew fans like the Clash and Pete Townshend to the band. Dan Alloway from KTEP’s “Folk Fury” show in El Paso calls Live Shots the “ultimate display of roots rock ’n’ roll energy,” while Jim Beal Jr. of San Antonio’s KSYM says he loves the inventive use of accordion and pedal steel in a rock ’n’ roll context. If you needed one album to show what’s wholly unique about this music, this is the one to grab.

A well-recorded document of one of the finest bands ever assembled, caught on a hot night in England. Ponty Bone’s Euro/Tex-Mex/Cajun accordion sets up some fiery guitar and pedal steel exchanges from Jesse Taylor and Lloyd Maines that manage to exceed the originals in spunk and attitude. Reese Wynans also pitches in with some tasty piano. Ely pours every ounce of heart and soul into the songs, making it easy to see what drew fans like the Clash and Pete Townshend to the band. Dan Alloway from KTEP’s “Folk Fury” show in El Paso calls Live Shots the “ultimate display of roots rock ’n’ roll energy,” while Jim Beal Jr. of San Antonio’s KSYM says he loves the inventive use of accordion and pedal steel in a rock ’n’ roll context. If you needed one album to show what’s wholly unique about this music, this is the one to grab.

2. Letter To Laredo, MCA, 1995

Kicking off with the absolutely killer “All Just To Get To You” and finishing up with the anthemic “A Thousand Miles From Home,” Letter To Laredo is an epic album. This mostly acoustic set introduces the flamenco guitar talents of Teye, who contributes dramatic coloring to the songs. Reuniting with original band members Ponty Bone and Lloyd Maines, Ely gets back to the kind of narrative material that graced his earliest work. This time the stories move south, a little closer to the Rio Grande. LoneStarMusic editor (and El Paso native) Richard Skanse ranks this as his favorite Ely album; he discovered it shortly before moving to New York City, and the Garcia Lorca-inspired border ballads helped ease his homesick blues. Also of note is the guest appearance by Bruce Springsteen, aka “the New Jersey Joe Ely,” who adds his vocal touch to the opening track and really shines.

Kicking off with the absolutely killer “All Just To Get To You” and finishing up with the anthemic “A Thousand Miles From Home,” Letter To Laredo is an epic album. This mostly acoustic set introduces the flamenco guitar talents of Teye, who contributes dramatic coloring to the songs. Reuniting with original band members Ponty Bone and Lloyd Maines, Ely gets back to the kind of narrative material that graced his earliest work. This time the stories move south, a little closer to the Rio Grande. LoneStarMusic editor (and El Paso native) Richard Skanse ranks this as his favorite Ely album; he discovered it shortly before moving to New York City, and the Garcia Lorca-inspired border ballads helped ease his homesick blues. Also of note is the guest appearance by Bruce Springsteen, aka “the New Jersey Joe Ely,” who adds his vocal touch to the opening track and really shines.

3. Joe Ely, MCA, 1977

The self-titled debut comes blasting out of the speakers with “Had My Hopes Up High”, recounting Ely’s ride-hitching travels over a country-boogie groove. About a minute and a half in, you get the most devastating guitar/pedal-steel trade off to ever grace a Nashville country album. Both Ely and Lloyd Maines credit producer Chip Young with being fearless in his approach to recording the band; he already had experience blurring the lines of country and rock ’n’ roll prior to taking on the Ely Band, and had the good sense to let them show their stuff. This record is also where you hear Ely’s original and definitive versions of Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s “Treat Me Like A Saturday Night” and Butch Hancock’s “If You Were a Bluebird” and “She Never Spoke Spanish To Me.” Steve Terrell, who spins records on Santa Fe’s KSFR, notes the cover drawing by his pal Paul Milosovitch is a cool bonus, too; it’s a portrait of the artist as a young hippy cowboy.

The self-titled debut comes blasting out of the speakers with “Had My Hopes Up High”, recounting Ely’s ride-hitching travels over a country-boogie groove. About a minute and a half in, you get the most devastating guitar/pedal-steel trade off to ever grace a Nashville country album. Both Ely and Lloyd Maines credit producer Chip Young with being fearless in his approach to recording the band; he already had experience blurring the lines of country and rock ’n’ roll prior to taking on the Ely Band, and had the good sense to let them show their stuff. This record is also where you hear Ely’s original and definitive versions of Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s “Treat Me Like A Saturday Night” and Butch Hancock’s “If You Were a Bluebird” and “She Never Spoke Spanish To Me.” Steve Terrell, who spins records on Santa Fe’s KSFR, notes the cover drawing by his pal Paul Milosovitch is a cool bonus, too; it’s a portrait of the artist as a young hippy cowboy.

4. Dig All Night, Hightone, 1988

The pair of albums Ely made for the independent Hightone label could be seen as two sides of the same coin, a powerful combination of the wizened, matured singer-songwriter and a take-no-prisoners powerhouse rock ’n’ roll band. Lord of the Highway is excellent, but I give the edge to Dig All Night, as the band really finds its groove and Ely delivers some of his best vocal performances. Jim Beal hails the opening “Settle For Love” as one of the ultimate love songs. Other sure bets here are “My Eyes Got Lucky,” “Maybe She’ll Find Me” and the driving title track.

The pair of albums Ely made for the independent Hightone label could be seen as two sides of the same coin, a powerful combination of the wizened, matured singer-songwriter and a take-no-prisoners powerhouse rock ’n’ roll band. Lord of the Highway is excellent, but I give the edge to Dig All Night, as the band really finds its groove and Ely delivers some of his best vocal performances. Jim Beal hails the opening “Settle For Love” as one of the ultimate love songs. Other sure bets here are “My Eyes Got Lucky,” “Maybe She’ll Find Me” and the driving title track.

5. Down on the Drag, MCA, 1979

Sorry Joe and Lloyd — just because the two of you have displayed the talent and judgment to be major components of countless great records, I’m still not accepting your dismissive opinions on this one. And I know I’m not alone in my love of the third Joe Ely album. Hancock contributes some of his finest writing, including the dark and soulful opener, “Fools Fall In Love.” Ed Vizard’s “BBQ and Foam,” despite its light-hearted title, is a somber ballad with a Levon Helm groove and one of Jesse Taylor’s most sparse and melodic solos. The title track (also by Hancock) gives a tip of the hat to Austin’s Guadalupe Street as well as the underground newspaper, The Rag. Maybe Ely’s concepts get a little confusing on “Crazy Lemon,” “Crawdad Train” and “She Leaves You Where You Are,” but I’m happy to keep listening until it all makes sense. An underrated classic.

Sorry Joe and Lloyd — just because the two of you have displayed the talent and judgment to be major components of countless great records, I’m still not accepting your dismissive opinions on this one. And I know I’m not alone in my love of the third Joe Ely album. Hancock contributes some of his finest writing, including the dark and soulful opener, “Fools Fall In Love.” Ed Vizard’s “BBQ and Foam,” despite its light-hearted title, is a somber ballad with a Levon Helm groove and one of Jesse Taylor’s most sparse and melodic solos. The title track (also by Hancock) gives a tip of the hat to Austin’s Guadalupe Street as well as the underground newspaper, The Rag. Maybe Ely’s concepts get a little confusing on “Crazy Lemon,” “Crawdad Train” and “She Leaves You Where You Are,” but I’m happy to keep listening until it all makes sense. An underrated classic.

Hey – from a newcomer to Joe Ely – thanks! I heard him all the time as a kid but was a young punk and foolishly ignored his live shows around town. I regret it now. I know I can still see him, and you’ve given me a bunch of great places to start with the records. Much appreciated.

Nice write up – I’m a longtime Joe fan since the 80s and I think your takes are spot-on. The album that was the biggest disappointment to me was Chicago 1987. You’re right that the tape was sped up; everything is a half-step sharp. I have a good ear for pitch and this was a real distraction for me, which really bugs me because I saw that band live many times and it was great. I’ve been meaning to create a speed-corrected version of the album.