By Richard Skanse

(March/April 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 2)

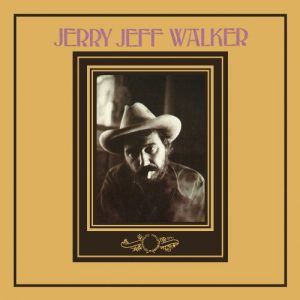

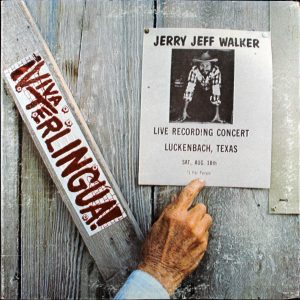

By the time Jerry Jeff Walker came sliding sideways into Luckenbach, the 31-year-old freewheeling drifter already had enough miles on his troubadour odometer to leave his standard manufacturer’s warranty in the dust. He had crisscrossed the country (and Canada, to boot) several times all through the ‘60s, recorded seven albums, parlayed a night in the pokey into an instant-classic Top 10 song, and even flirted with a burnout-and-cocaine-induced early retirement in too-sunny Key West. But a recent move to Austin and a fortuitous hook-up with the perfect band of like-minded musical gonzos had jumpstarted his muse again, as proven straight away on his first Texas album, 1972’s Jerry Jeff Walker. But the record Walker and his merry men cooked up the following year in Luckenbach — ¡Viva Terlingua! — heralded his true arrival. “Mr. Bojangles,” the aforementioned Top 10 hit (courtesy of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s cover, one of the first of many), would forever be his most famous song, but the Jerry Jeff Walker most fans know and love was born fully grown in that Texas ghost town in the summer of 1973. After that, everything he’d done before during his previous incarnation as a rambling folk singer seemed — much like fellow cosmic country icon Willie Nelson’s pre-Austin stint as a short-haired, clean-shaven Nashville songwriter — like a curious footnote to the Jerry Jeff legend.

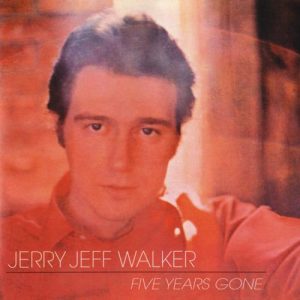

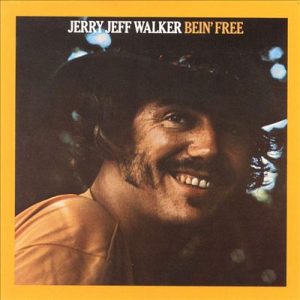

A statement like that requires an asterisk of its own, of course, lest it be misconstrued as a flip dismissal of Walker’s early catalog. The four solo albums Walker cut between 1968 and 1970 — Mr. Bojangles, Driftin’ Way of Life, Five Years Gone, and Bein’ Free — all hold up as among his very best as a songwriter, and many of his songs from those records remain staples of his live set to this day. Indeed, Walker’s return to solo-acoustic theater performances in recent years harkens back to his folk days a lot more than to his rowdy progressive-country run of the ‘70s. And again like Willie’s Nashville days, those early records represent Walker’s most prolific period as a writer; after 1969’s Driftin’ Way of Life, it would be 27 years before he recorded another album comprised of all of his own songs — 1996’s Scamp.

Scamp came in the middle of the third (and latest) stage of Walker’s recording career, which began in the mid-80s when he hopped off the major-label train and began releasing his albums on his own Tried and True Music label. There’s keepers in that bunch, too, and Walker’s pioneering DIY business model has proven to be as influential to later generations of independent Texas artists as his music.

All that said, though, the records Walker made for MCA during his peak “wild years” (1972-1978) still hold up as far and away the funnest he’s ever made, if not the funnest to ever come out the Austin scene, period. Pity half those records he made during that epic run are long out of print.

As a teenager, Walker (born Ronald Clyde Crosby) played in a band in his native Oneonta, N.Y., called the Tones. But his real musical journey began after high school (and a brief fling with the National Guard), when he hit the road as an itinerant, ukulele-and-guitar strumming folk/street singer. Inspired by the gypsy songman lifestyle of folk heroes Woody Guthrie and Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, he drifted around the country for the better part of the ‘60s, with extended stops in New Orleans, Houston, and New York City’s Greenwich Village. Along the way, he stockpiled songs, met the a man he’d immortalize in “Mr. Bojangles,” and introduced one Townes Van Zandt to one Guy Clark when they were all playing the folk clubs in Houston. Later on in his career, Walker would record many of Clark’s most famous songs, but at the time when they first met, Clark had not yet discovered his own voice. As Walker recalled in the liner notes to 1972’s Jerry Jeff Walker: “[Guy] told me once, ‘You know, I used to hear you and Townes play a new song every couple of days, but it never dawned on me that I could just write one of my own.’ O.K., Sleepy John, it never dawned on me to build my own guitar, either.”

Houston was also where Walker met Bob Bruno, who he describes in his 1999 autobiography, Gypsy Songman, as “the epitome of a New York City jazz player.” Together with Walker’s buddy Pete Troutner, bassist Gary P. White (who was working at NASA at the time), and drummer David Scherstrom, they formed a psychedelic folk-rock-jazz combo called the Lost Sea Dreamers. They eventually found their way back up East and signed to Vanguard Records, which requested a name change that couldn’t be abbreviated to “L.S.D.” They rechristened themselves Circus Maximus and recorded two albums for Vanguard before imploding: 1967’s Circus Maximus and 1968’s Neverland Revisited.

Houston was also where Walker met Bob Bruno, who he describes in his 1999 autobiography, Gypsy Songman, as “the epitome of a New York City jazz player.” Together with Walker’s buddy Pete Troutner, bassist Gary P. White (who was working at NASA at the time), and drummer David Scherstrom, they formed a psychedelic folk-rock-jazz combo called the Lost Sea Dreamers. They eventually found their way back up East and signed to Vanguard Records, which requested a name change that couldn’t be abbreviated to “L.S.D.” They rechristened themselves Circus Maximus and recorded two albums for Vanguard before imploding: 1967’s Circus Maximus and 1968’s Neverland Revisited.

Only the self-titled debut has seen reissue in the CD age, but the 1999 Walker compilation Best of the Vanguard Years gives a fair enough sample of his songwriting and singing contributions to both albums, with three of his four tracks from Circus Maximus and and four of his five from Neverland. (The remaining Circus Maximus songs, including the debut’s minor FM radio hit, “Wind,” were written by Bruno.) Walker’s songs provided the folk half of the band’s folk-jazz fusion, though they sound nothing like most of the solo fare he’d begin recording soon after.  Out of the selections featured on Best of the Vanguard Years, highlights include Neverland Revisted’s trippy “Trying to Live Right,” with Walker spitting rapid-fire, almost rap-style verses over rolling organ, and the languid and surreal “Hansel and Gretel.” From the first album, “Lost Sea Shanty” and “Oops I Can Dance” both have a jangling, Byrds-y vibe. Vocally, Walker sounded more than a little like mid-to-late-60s era Neil Diamond, albeit without the irresistibly charming hooks. His best was yet to come.

Out of the selections featured on Best of the Vanguard Years, highlights include Neverland Revisted’s trippy “Trying to Live Right,” with Walker spitting rapid-fire, almost rap-style verses over rolling organ, and the languid and surreal “Hansel and Gretel.” From the first album, “Lost Sea Shanty” and “Oops I Can Dance” both have a jangling, Byrds-y vibe. Vocally, Walker sounded more than a little like mid-to-late-60s era Neil Diamond, albeit without the irresistibly charming hooks. His best was yet to come.

Right after Circus Maximus folded tent, Walker began his solo recording career in earnest. In between the band’s two albums, he began hanging around the Village scene with guitarist David Bromberg, and it was with Bromberg that he popped into New York radio station WBAI one night to play on DJ Bob Fass’ freeform midnight-to-dawn show. The duo played Walker’s as-yet-unrecorded “Mr. Bojangles” live on the air, and Fass and his audience were so taken with it that the DJ started playing his live recording of the song in frequent rotation. Out of thin air (literally), Walker had an underground hit on his hands, ripe to capitalize on — but Vanguard, which Walker was still signed to after Circus Maximus broke up, passed on the opportunity to claim dibs on it. According to Walker, the label’s president mistakenly assumed the Bojangles character was a black man and deemed the song — particularly in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s recent assassination — “a little bit racist.” Nevertheless, Vanguard gave Walker a hall pass to try his luck with another label, provided that he still come back to complete his original contract with another record. Atco, a division of Atlantic Records, quickly jumped in, resulting in Walker closing out the decade with two albums for Atco (1968’s Mr. Bojangles and 1969’s Five Years Gone) and a third for Vanguard, 1969’s Driftin’ Way of Life. Atco would also release his fourth solo album, 1970’s Bein’ Free. All four titles remain available on CD and as legal downloads.

Right after Circus Maximus folded tent, Walker began his solo recording career in earnest. In between the band’s two albums, he began hanging around the Village scene with guitarist David Bromberg, and it was with Bromberg that he popped into New York radio station WBAI one night to play on DJ Bob Fass’ freeform midnight-to-dawn show. The duo played Walker’s as-yet-unrecorded “Mr. Bojangles” live on the air, and Fass and his audience were so taken with it that the DJ started playing his live recording of the song in frequent rotation. Out of thin air (literally), Walker had an underground hit on his hands, ripe to capitalize on — but Vanguard, which Walker was still signed to after Circus Maximus broke up, passed on the opportunity to claim dibs on it. According to Walker, the label’s president mistakenly assumed the Bojangles character was a black man and deemed the song — particularly in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s recent assassination — “a little bit racist.” Nevertheless, Vanguard gave Walker a hall pass to try his luck with another label, provided that he still come back to complete his original contract with another record. Atco, a division of Atlantic Records, quickly jumped in, resulting in Walker closing out the decade with two albums for Atco (1968’s Mr. Bojangles and 1969’s Five Years Gone) and a third for Vanguard, 1969’s Driftin’ Way of Life. Atco would also release his fourth solo album, 1970’s Bein’ Free. All four titles remain available on CD and as legal downloads.

Vanguard may have missed the “Bojangles” boat, but it lucked out with the pick of Walker’s first solo litter. Although all four albums are highly recommended listens for Walker fans and aficionados of the singer-songwriter genre, Driftin’ Way of Life is the real charmer of the bunch. Its 11 Walker originals — including such enduring classics as the toe-tapping title track and the lovely “Morning Song to Sally” — fit together like pages from a hitchhiking minstrel’s road journal, which of course it is. The album tells you virtually everything you need to know about Walker’s life during his walkabout days in the ‘60s, just a strummin’ and singin’ and lovin’ (and leavin’) from town to town without a care in the world, and he makes it sound so much fun (for the most part), it’s a wonder he ever stopped. The rustic folk-country sound that pervades the record is closer in spirit to Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and New Morning than it is to Walker’s gonzo records of the ‘70s, but in hindsight, it’s clear which way the wind was blowing him.

Vanguard may have missed the “Bojangles” boat, but it lucked out with the pick of Walker’s first solo litter. Although all four albums are highly recommended listens for Walker fans and aficionados of the singer-songwriter genre, Driftin’ Way of Life is the real charmer of the bunch. Its 11 Walker originals — including such enduring classics as the toe-tapping title track and the lovely “Morning Song to Sally” — fit together like pages from a hitchhiking minstrel’s road journal, which of course it is. The album tells you virtually everything you need to know about Walker’s life during his walkabout days in the ‘60s, just a strummin’ and singin’ and lovin’ (and leavin’) from town to town without a care in the world, and he makes it sound so much fun (for the most part), it’s a wonder he ever stopped. The rustic folk-country sound that pervades the record is closer in spirit to Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and New Morning than it is to Walker’s gonzo records of the ‘70s, but in hindsight, it’s clear which way the wind was blowing him.

Kicking off with another mini-autobiography-in-song, “Gypsy Songman,” Mr. Bojangles is, for the most part, cut from similar cloth as Driftin’ Way of Life, and arguably just as good when broken down song by song if not quite as so much as a whole. Both albums make fine use of Walker’s friend Bromberg on guitar, and Mr. Bojangles has, of course, “Mr. Bojangles” (along with “Little Bird,” the feisty “I Makes Money (Money Don’t Make Me),” and the wistful “Old Man”). It’s also a tad more eclectic, mainly thanks to the rather bizarre “The Ballad of the Hulk,” a nearly eight-minute screed against war, politicians, the economy, hypocritical priests, petty society in general and, just for good measure, the record industry. The track’s simmering jam-rock groove, sprinkled with jazzy guitar solos, plays like an LSD-addled Circus Maximus flashback; it’s more interesting than it is actually enjoyable, weighing down the second half of the album like a Hulk-sized bummer.

Walker finished out his Atco contract with Five Years Gone and Bein’ Free. You can actually judge both pretty accurately by their cover photos. The woefully underrated Five Years Gone, with its red-tinted portrait of a clean-shaven, serious-looking Walker in a button-up shirt, is an introspective beauty of a classic early-70s singer-songwriter record that’s barely folky and not a bit country. A couple of songs pick up the pace a little (namely the cover of Michael Martin Murphy’s “Tracks Run Through the City” and the closing “Born to Sing a Dancin’ Song,” which sounds like a stowaway from the Bojangles or Driftin’ sessions), but mostly this is an album best heard late at night with a mind geared for quiet reflection. (The version of “Mr. Bojangles” included on the Five Years reissue is a nice surprise; it’s the original live version Walker and Bromberg played on Bob Fass’ WBAI radio show, complete with the DJ’s awed reaction at the end: “That is a beautiful song. You wrote that? Wow.”)

Walker finished out his Atco contract with Five Years Gone and Bein’ Free. You can actually judge both pretty accurately by their cover photos. The woefully underrated Five Years Gone, with its red-tinted portrait of a clean-shaven, serious-looking Walker in a button-up shirt, is an introspective beauty of a classic early-70s singer-songwriter record that’s barely folky and not a bit country. A couple of songs pick up the pace a little (namely the cover of Michael Martin Murphy’s “Tracks Run Through the City” and the closing “Born to Sing a Dancin’ Song,” which sounds like a stowaway from the Bojangles or Driftin’ sessions), but mostly this is an album best heard late at night with a mind geared for quiet reflection. (The version of “Mr. Bojangles” included on the Five Years reissue is a nice surprise; it’s the original live version Walker and Bromberg played on Bob Fass’ WBAI radio show, complete with the DJ’s awed reaction at the end: “That is a beautiful song. You wrote that? Wow.”)  Bein’ Free, released the following year, has its share of quiet moments, too — including the classic “Stoney” — but the Walker pictured on the cover — cowboy hat, scruffy sideburns, mustache and big happy grin — could not look more different from the sensitive-but-conservative-looking gent on Five Years Gone. He cut the record in Florida with a bunch of veteran rhythm ’n’ blues players (including Memphis all-stars Jim Dickinson and Charlie Freeman and Dallas harmonica ace Don Brooks), but the album’s best and loosest tracks (most notably the ramshackle, laugh-along opener, “I’m Gonna Tell on You”) herald the dawn of his golden progressive country era. All he had left to do was move to Texas.

Bein’ Free, released the following year, has its share of quiet moments, too — including the classic “Stoney” — but the Walker pictured on the cover — cowboy hat, scruffy sideburns, mustache and big happy grin — could not look more different from the sensitive-but-conservative-looking gent on Five Years Gone. He cut the record in Florida with a bunch of veteran rhythm ’n’ blues players (including Memphis all-stars Jim Dickinson and Charlie Freeman and Dallas harmonica ace Don Brooks), but the album’s best and loosest tracks (most notably the ramshackle, laugh-along opener, “I’m Gonna Tell on You”) herald the dawn of his golden progressive country era. All he had left to do was move to Texas.

Jerry Jeff Walker (MCA, 1972) is where the good times really start rolling. The album found Walker teamed for the first time with Texans Gary P. Nunn, Bob Livingston, Craig Hills, Michael McGeary, and Herb Steiner (later known as the Lost Gonzo Band), and it was mostly recorded direct to tape (sans fancy studio board) inside an old Austin dry cleaners building. A host of other players (including Bromberg and Murphey) joined the fun during the mixing of the record in New York, making for what Walker called “a real hobo cluster-fuck,” and every note of the album sounds like a happy accident. It’s an end-to-end delight and stacked with classics, including Walker’s own “Hill Country Rain,” “Charlie Dunn,” “Her Good Lovin’ Grace,” and “Hairy Ass Hillbillies,” as well as his first two Guy Clark covers, “That Old Time Feeling” and “L.A. Freeway.” Clark himself would only barely improve on those two when he finally got around to recording his stone-cold perfect debut, 1975’s Old No. 1. Though long out-of-print in the States, Jerry Jeff Walker was finally issued on CD by the Australian label Raven Records in 2011 — and it’s worth every penny for the import. Or better yet, hunt down a vintage copy on cracklin’ vinyl, if only for Walker’s fun song-by-song notes on the original back cover.

Jerry Jeff Walker (MCA, 1972) is where the good times really start rolling. The album found Walker teamed for the first time with Texans Gary P. Nunn, Bob Livingston, Craig Hills, Michael McGeary, and Herb Steiner (later known as the Lost Gonzo Band), and it was mostly recorded direct to tape (sans fancy studio board) inside an old Austin dry cleaners building. A host of other players (including Bromberg and Murphey) joined the fun during the mixing of the record in New York, making for what Walker called “a real hobo cluster-fuck,” and every note of the album sounds like a happy accident. It’s an end-to-end delight and stacked with classics, including Walker’s own “Hill Country Rain,” “Charlie Dunn,” “Her Good Lovin’ Grace,” and “Hairy Ass Hillbillies,” as well as his first two Guy Clark covers, “That Old Time Feeling” and “L.A. Freeway.” Clark himself would only barely improve on those two when he finally got around to recording his stone-cold perfect debut, 1975’s Old No. 1. Though long out-of-print in the States, Jerry Jeff Walker was finally issued on CD by the Australian label Raven Records in 2011 — and it’s worth every penny for the import. Or better yet, hunt down a vintage copy on cracklin’ vinyl, if only for Walker’s fun song-by-song notes on the original back cover.

¡Viva Terlingua! (MCA, 1973) was even better. Never a fan of traditional studio environments, Walker moved his new Gonzo gang — and a state-of-the-art mobile recording unit — out to the dancehall in his buddy Hondo Crouch’s Hill Country hamlet of Luckenbach, and very casually knocked out one of the all-time greatest records in Texas music. Seven of the album’s nine tracks were cut “studio-style” (sans rowdy audience), but the immortal cover of Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” and Nunn’s even more famous “London Homesick Blues” (sung by Nunn himself) were both captured during the impromptu live concert the band threw at the end of the week. Walker also nailed another Clark classic, “Desperados Waiting for the Train,” and Murphey’s “Backslider’s Wine,” and revisited his own “Little Bird” (originally on Mr. Bojangles), giving the song as much of a total Texas makeover as he himself had undergone. But the two songs that best captured the “wish you were here” spirit of the record were his brand new “Sangria Wine” and the opening “Gettin’ By.” His “Don’t matter how you do it, just do it like you know it” line in the latter’s opening verse oughta be his epitaph.

¡Viva Terlingua! (MCA, 1973) was even better. Never a fan of traditional studio environments, Walker moved his new Gonzo gang — and a state-of-the-art mobile recording unit — out to the dancehall in his buddy Hondo Crouch’s Hill Country hamlet of Luckenbach, and very casually knocked out one of the all-time greatest records in Texas music. Seven of the album’s nine tracks were cut “studio-style” (sans rowdy audience), but the immortal cover of Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” and Nunn’s even more famous “London Homesick Blues” (sung by Nunn himself) were both captured during the impromptu live concert the band threw at the end of the week. Walker also nailed another Clark classic, “Desperados Waiting for the Train,” and Murphey’s “Backslider’s Wine,” and revisited his own “Little Bird” (originally on Mr. Bojangles), giving the song as much of a total Texas makeover as he himself had undergone. But the two songs that best captured the “wish you were here” spirit of the record were his brand new “Sangria Wine” and the opening “Gettin’ By.” His “Don’t matter how you do it, just do it like you know it” line in the latter’s opening verse oughta be his epitaph.

After ¡Viva Terlingua!, Walker recorded five more albums for MCA that kept delivering the goods in highly satisfying fashion: 1974’s Walker’s Collectibles, 1975’s Ridin’ High, 1976’s It’s a Good Night for Singin’, 1977’s A Man Must Carry On, and 1978’s Contrary to Ordinary. Out of that bunch, only Ridin’ High and A Man Must Carry On have ever been issued on CD and as legal downloads, though Australia’s Raven label is set to release Walker’s Collectibles on CD this April and will hopefully follow suit with the others down the line. The rousing Walker’s Collectibles, which added a few horns to the Gonzo stew, was his last album of the decade comprised mostly of his own songs (including another remake from Mr. Bojangles, “My Old Man”), along with two more Nunn tunes (“Rock Me Roll Me” and the moody “Well of the Blues”). Ridin’ High featured only two Walker originals (the tender “I Love You” and the uproarious “Pissin’ in the Wind”), but there’s no knocking his taste in picking great material: Clark’s “Like a Coat from the Cold,” Willie Nelson’s “Pick Up the Tempo,” Chuck Pyle’s “Jaded Lover,” Jesse Winchester’s “Mississippi You’re on My Mind” and especially Michael Burton’s “Night Rider’s Lament” all rank high amongst Walker’s best moments on record.

After ¡Viva Terlingua!, Walker recorded five more albums for MCA that kept delivering the goods in highly satisfying fashion: 1974’s Walker’s Collectibles, 1975’s Ridin’ High, 1976’s It’s a Good Night for Singin’, 1977’s A Man Must Carry On, and 1978’s Contrary to Ordinary. Out of that bunch, only Ridin’ High and A Man Must Carry On have ever been issued on CD and as legal downloads, though Australia’s Raven label is set to release Walker’s Collectibles on CD this April and will hopefully follow suit with the others down the line. The rousing Walker’s Collectibles, which added a few horns to the Gonzo stew, was his last album of the decade comprised mostly of his own songs (including another remake from Mr. Bojangles, “My Old Man”), along with two more Nunn tunes (“Rock Me Roll Me” and the moody “Well of the Blues”). Ridin’ High featured only two Walker originals (the tender “I Love You” and the uproarious “Pissin’ in the Wind”), but there’s no knocking his taste in picking great material: Clark’s “Like a Coat from the Cold,” Willie Nelson’s “Pick Up the Tempo,” Chuck Pyle’s “Jaded Lover,” Jesse Winchester’s “Mississippi You’re on My Mind” and especially Michael Burton’s “Night Rider’s Lament” all rank high amongst Walker’s best moments on record.  The Lost Gonzos contribute mightily, too, via new recruit John Inmon’s excellent “Goodbye Easy Street” and Livingston and Nunn’s “Public Domain” (next to “Pissin’ in the Wind,” the funniest song in the Walker canon.) The following year’s It’s a Good Night for Singin’ was just as good, with the lone Walker original — a remake of Bein’ Free’s “Stoney” — leaving plenty of room for another batch of grade-A covers — including Tom Waits’ “Looking for the Heart of Saturday Night,” Butch Hancock’s “Standin’ at the Big Hotel,” and Billy Joe Shaver’s “Old Five and Dimers Like Me” — and more choice cuts from his band, like Livingston’s title track and Nunn’s achingly bittersweet “Couldn’t Do Nothin’ Right.”

The Lost Gonzos contribute mightily, too, via new recruit John Inmon’s excellent “Goodbye Easy Street” and Livingston and Nunn’s “Public Domain” (next to “Pissin’ in the Wind,” the funniest song in the Walker canon.) The following year’s It’s a Good Night for Singin’ was just as good, with the lone Walker original — a remake of Bein’ Free’s “Stoney” — leaving plenty of room for another batch of grade-A covers — including Tom Waits’ “Looking for the Heart of Saturday Night,” Butch Hancock’s “Standin’ at the Big Hotel,” and Billy Joe Shaver’s “Old Five and Dimers Like Me” — and more choice cuts from his band, like Livingston’s title track and Nunn’s achingly bittersweet “Couldn’t Do Nothin’ Right.”

Maybe Livingston, Nunn and Co. were just a little too good, because after A Good Night for Singin’, the whole Lost Gonzo Band landed its own record deal with MCA. Walker quickly pulled together a new group — the Bandito Band — comprised of guitarists Bobby Rambo and Dave Perkins, drummer Freddie Krc, bassist/sax player Ron Cobb, and horn player Tomas Ramirez. Both the Gonzos and the Banditos are featured on A Man Must Carry On, a double-album hodgepodge of studio cuts, live tracks from the road, and a smattering of spoken word pieces by poet Charles John Quarto and Walker’s late Luckenbach friend Hondo Crouch, to whom the album was dedicated. It’s a sprawling, throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks affair, which, naturally, makes it a perfect time capsule for Walker at his high flyin’ (and ridin’) wild ’70s peak (the tracks were recorded over a span of two years, accounting for 82 boxes of tape to choose from).

Maybe Livingston, Nunn and Co. were just a little too good, because after A Good Night for Singin’, the whole Lost Gonzo Band landed its own record deal with MCA. Walker quickly pulled together a new group — the Bandito Band — comprised of guitarists Bobby Rambo and Dave Perkins, drummer Freddie Krc, bassist/sax player Ron Cobb, and horn player Tomas Ramirez. Both the Gonzos and the Banditos are featured on A Man Must Carry On, a double-album hodgepodge of studio cuts, live tracks from the road, and a smattering of spoken word pieces by poet Charles John Quarto and Walker’s late Luckenbach friend Hondo Crouch, to whom the album was dedicated. It’s a sprawling, throw-everything-at-the-wall-and-see-what-sticks affair, which, naturally, makes it a perfect time capsule for Walker at his high flyin’ (and ridin’) wild ’70s peak (the tracks were recorded over a span of two years, accounting for 82 boxes of tape to choose from).  The cover of Rusty Wier’s “Don’t It Make You Wanna Dance?” is probably the album’s most famous cut, but the all-live “side four” of the original release was the real highlight — kicking off with an epic, six-minute “Mr. Bojangles” and a roaring “L.A. Freeway” and coming to a head with “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” — this time with writer Ray Wylie Hubbard and Willie Nelson both joining in the fun. Maddeningly, MCA split the original double vinyl album onto two separate CDs, titled Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, and the album remains split that way as a download, too. But don’t even think of buying one “volume” and not the other; like all the best double albums of the decade, A Man Must Carry On is best appreciated all the way through.

The cover of Rusty Wier’s “Don’t It Make You Wanna Dance?” is probably the album’s most famous cut, but the all-live “side four” of the original release was the real highlight — kicking off with an epic, six-minute “Mr. Bojangles” and a roaring “L.A. Freeway” and coming to a head with “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” — this time with writer Ray Wylie Hubbard and Willie Nelson both joining in the fun. Maddeningly, MCA split the original double vinyl album onto two separate CDs, titled Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, and the album remains split that way as a download, too. But don’t even think of buying one “volume” and not the other; like all the best double albums of the decade, A Man Must Carry On is best appreciated all the way through.

After sharing space with the exiting Lost Gonzos on A Man Must Carry On, the Bandito Band made its full-fledged debut on 1978’s Contrary to Ordinary. You can hear the changing of the guard loud and clear on tracks like Butch Hancock’s “Suckin’ on a Bottle of Gin,” where the brassy horns dominate the mix. (Joe Ely’s version from the previous year remains definitive.) The record fares better with the (contrary to ordinary) more mellow fare, like Rodney Crowell’s “Till I Gain Control Again,” Billy Jim Baker’s title track, and Susanna (wife of Guy) Clark’s “We Were Kinda Crazy Then.” Walker has called Contrary to Ordinary one of his favorite records, and it does have its charms, but it’s arguably the weakest of his ’70s MCA era.

After sharing space with the exiting Lost Gonzos on A Man Must Carry On, the Bandito Band made its full-fledged debut on 1978’s Contrary to Ordinary. You can hear the changing of the guard loud and clear on tracks like Butch Hancock’s “Suckin’ on a Bottle of Gin,” where the brassy horns dominate the mix. (Joe Ely’s version from the previous year remains definitive.) The record fares better with the (contrary to ordinary) more mellow fare, like Rodney Crowell’s “Till I Gain Control Again,” Billy Jim Baker’s title track, and Susanna (wife of Guy) Clark’s “We Were Kinda Crazy Then.” Walker has called Contrary to Ordinary one of his favorite records, and it does have its charms, but it’s arguably the weakest of his ’70s MCA era.  He then closed out the decade with a label change, recording both 1978’s Jerry Jeff (aka the “Red, White & Blue Album”) and ’79’s Too Old to Change for Elektra (both are available as downloads). Jerry Jeff is pretty much a loud and cocky rock record (Lee Clayton’s “Lone Wolf,” Rambo’s “Boogie Mama”), but once again it’s the slower stuff that sticks best: Guy Clark’s “Comfort and Crazy,” Crowell’s “Banks of the Old Bandera,” and the opening “Eastern Avenue River Railway Blues,” a Mike Reid song given a grand, piano-driven arrangement reminiscent of early Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. Walker’s update of his own breezy “Her Good Lovin’ Grace” (first recorded on ’72’s Jerry Jeff Walker) was another standout, though it doesn’t improve much upon the original.

He then closed out the decade with a label change, recording both 1978’s Jerry Jeff (aka the “Red, White & Blue Album”) and ’79’s Too Old to Change for Elektra (both are available as downloads). Jerry Jeff is pretty much a loud and cocky rock record (Lee Clayton’s “Lone Wolf,” Rambo’s “Boogie Mama”), but once again it’s the slower stuff that sticks best: Guy Clark’s “Comfort and Crazy,” Crowell’s “Banks of the Old Bandera,” and the opening “Eastern Avenue River Railway Blues,” a Mike Reid song given a grand, piano-driven arrangement reminiscent of early Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. Walker’s update of his own breezy “Her Good Lovin’ Grace” (first recorded on ’72’s Jerry Jeff Walker) was another standout, though it doesn’t improve much upon the original.  Walker didn’t write a note on Too Old to Change (made when Walker was all of 37 years old), but the songs all come across as very personal snapshots of a man who very much was ready for a change. His cover of “Ain’t Living Long Like This” doesn’t hold a candle to Waylon’s, Emmylou’s, or Crowell’s original, but if nothing else, he packs it with conviction. The rest of the album is considerably more mellow — the sound of one of the ‘70s most notorious devil-may-care partiers coasting to a long, slow stop with nothing but fumes left in the tank. As he noted pointedly in his autobiography: “The day after I walked out of the studio, I gave up drugs, whiskey, cigarettes, and red meat.”

Walker didn’t write a note on Too Old to Change (made when Walker was all of 37 years old), but the songs all come across as very personal snapshots of a man who very much was ready for a change. His cover of “Ain’t Living Long Like This” doesn’t hold a candle to Waylon’s, Emmylou’s, or Crowell’s original, but if nothing else, he packs it with conviction. The rest of the album is considerably more mellow — the sound of one of the ‘70s most notorious devil-may-care partiers coasting to a long, slow stop with nothing but fumes left in the tank. As he noted pointedly in his autobiography: “The day after I walked out of the studio, I gave up drugs, whiskey, cigarettes, and red meat.”

The ’80s would bring even more change for Walker, beginning with a brief return to MCA for two more records: 1981’s Reunion and ’82’s Cowjazz (both are long out of print). In his book, Walker notes that Reunion was recorded in Muscle Shoals with only Rambo left from his own band; the title referred to “someone coming back to himself, my own ‘reunion.’” Songs included fresh takes on Bein’ Free’s “Maybe Mexico” and Driftin’s “Morning Song to Sally,” plus a newer song, “For Little Jessie (She Knows Her Daddy Sings),” that he wrote for his daughter.

The ’80s would bring even more change for Walker, beginning with a brief return to MCA for two more records: 1981’s Reunion and ’82’s Cowjazz (both are long out of print). In his book, Walker notes that Reunion was recorded in Muscle Shoals with only Rambo left from his own band; the title referred to “someone coming back to himself, my own ‘reunion.’” Songs included fresh takes on Bein’ Free’s “Maybe Mexico” and Driftin’s “Morning Song to Sally,” plus a newer song, “For Little Jessie (She Knows Her Daddy Sings),” that he wrote for his daughter.  Cowjazz offered Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” Tom Waits’ “Old ’59,” and, most intriguingly, Bob Bruno’s “Wind” — the one minor hit off of the debut Circus Maximus album 15 years earlier. “I had come full circle,” wrote Walker. “‘Wind’ was the last song I would cut for a major label.”

Cowjazz offered Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” Tom Waits’ “Old ’59,” and, most intriguingly, Bob Bruno’s “Wind” — the one minor hit off of the debut Circus Maximus album 15 years earlier. “I had come full circle,” wrote Walker. “‘Wind’ was the last song I would cut for a major label.”

Walker launched his DIY era four years later with Gypsy Songman (Tried & True Music, 1986), a career overview comprised of new recordings of may of his most popular and/or favorite songs. Originally released only on cassette tape, it was eventually issued on CD when Walker and his manager/label boss (his wife, Susan) secured distribution through Rykodisc. He closed out the decade with Live at Gruene Hall (T&TM/Ryko, 1989), and by the ‘90s, he was back at his prolific pace full speed, knocking out two more live records and six studio albums before the turn of the century. The last decade has produced three more.

Walker launched his DIY era four years later with Gypsy Songman (Tried & True Music, 1986), a career overview comprised of new recordings of may of his most popular and/or favorite songs. Originally released only on cassette tape, it was eventually issued on CD when Walker and his manager/label boss (his wife, Susan) secured distribution through Rykodisc. He closed out the decade with Live at Gruene Hall (T&TM/Ryko, 1989), and by the ‘90s, he was back at his prolific pace full speed, knocking out two more live records and six studio albums before the turn of the century. The last decade has produced three more.

The Live at Gruene Hall album went a long way towards putting Walker back on the map and introducing his music to a new generation of Texas music fans; but out of the three live records he’s released since launching Tried & True, it’s by far the weakest. Walker sounds in good voice; the band he assembled for the project is top notch — Lloyd Maines, Champ Hood, John Inmon, Johnny Gimble, Roland Denney, and Brian Piper; and the material, mostly new, is strong enough.

The Live at Gruene Hall album went a long way towards putting Walker back on the map and introducing his music to a new generation of Texas music fans; but out of the three live records he’s released since launching Tried & True, it’s by far the weakest. Walker sounds in good voice; the band he assembled for the project is top notch — Lloyd Maines, Champ Hood, John Inmon, Johnny Gimble, Roland Denney, and Brian Piper; and the material, mostly new, is strong enough.  But any excitement or energy in the legendary dancehall that night sure didn’t stick to tape; it sounds like it was recorded at a soundcheck to an empty room. You don’t even hear a rowdy cheer when Willie Nelson shows up to duet with Walker on Steven Fromholz’s excellent “The Man with the Big Hat” — but that’s not the crowd’s fault, because Nelson wasn’t even there at the taping; his vocal was overdubbed in post-production.

But any excitement or energy in the legendary dancehall that night sure didn’t stick to tape; it sounds like it was recorded at a soundcheck to an empty room. You don’t even hear a rowdy cheer when Willie Nelson shows up to duet with Walker on Steven Fromholz’s excellent “The Man with the Big Hat” — but that’s not the crowd’s fault, because Nelson wasn’t even there at the taping; his vocal was overdubbed in post-production.  (Presumably, Walker’s “why don’t you join Willie and I while we sing it” introduction was overdubbed, too.) By refreshing contrast, Viva Luckenbach (T&TM/Ryko, 1994) sounds like a true celebration shared by band and fans alike, and the rousing Night after Night (T&TM, 1995), boasting an all-killer, no-filler set list of fan favorites recorded over three nights at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Va., drips sweat right out of your speakers. “If you were there, this is what you heard,” Walker writes in the liners. “No overdubs, no new vocals, no nothin’.” Which of course is how it should be.

(Presumably, Walker’s “why don’t you join Willie and I while we sing it” introduction was overdubbed, too.) By refreshing contrast, Viva Luckenbach (T&TM/Ryko, 1994) sounds like a true celebration shared by band and fans alike, and the rousing Night after Night (T&TM, 1995), boasting an all-killer, no-filler set list of fan favorites recorded over three nights at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Va., drips sweat right out of your speakers. “If you were there, this is what you heard,” Walker writes in the liners. “No overdubs, no new vocals, no nothin’.” Which of course is how it should be.

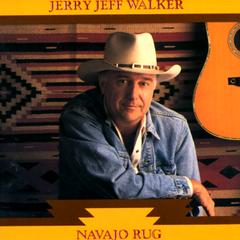

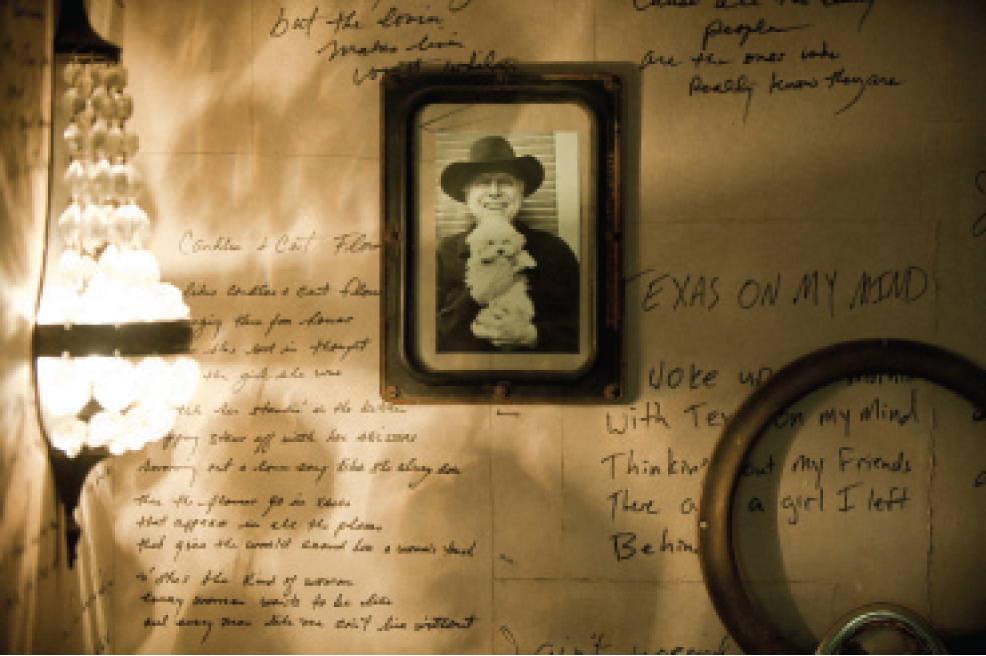

Walker’s Tried & True studio albums of the last 20 years have all been uniformly solid, albeit sometimes a little hard to tell apart — mainly because so many of them share such similar covers (more often than not, a close-up of a smiling, silver-haired Walker in a cowboy hat.) Most were co-produced by Walker and Lloyd Maines and feature variations of the same “Gonzo Compadres” lineup of Lost Gonzo and Bandito Band vets. The first two are the best. Navajo Rug (T&TM/Ryko, 1991) opens with the irresistible Ian Tyson/Tom Russell title track, and the feel-good vibe never lets up through a mostly up-tempo set of catchy songs by Walker (“Just to Celebrate,” “Nolan Ryan (He’s a Hero to Us All)”), Guy Clark (“All Through Throwing Good Love After Bad”), and Steven Fromholz (“Rockin’ on the River”).

Walker’s Tried & True studio albums of the last 20 years have all been uniformly solid, albeit sometimes a little hard to tell apart — mainly because so many of them share such similar covers (more often than not, a close-up of a smiling, silver-haired Walker in a cowboy hat.) Most were co-produced by Walker and Lloyd Maines and feature variations of the same “Gonzo Compadres” lineup of Lost Gonzo and Bandito Band vets. The first two are the best. Navajo Rug (T&TM/Ryko, 1991) opens with the irresistible Ian Tyson/Tom Russell title track, and the feel-good vibe never lets up through a mostly up-tempo set of catchy songs by Walker (“Just to Celebrate,” “Nolan Ryan (He’s a Hero to Us All)”), Guy Clark (“All Through Throwing Good Love After Bad”), and Steven Fromholz (“Rockin’ on the River”).  Hill Country Rain (T&TM/Ryko, 1992) follows suit, kicking off with Walker’s most defiant anthem since his ‘70s heyday, “Rock and Roll My Baby,” and closing with an anthemic remake of the title track (first heard on ’72’s Jerry Jeff Walker).

Hill Country Rain (T&TM/Ryko, 1992) follows suit, kicking off with Walker’s most defiant anthem since his ‘70s heyday, “Rock and Roll My Baby,” and closing with an anthemic remake of the title track (first heard on ’72’s Jerry Jeff Walker).

After 1994’s self-explanatory Christmas Gonzo Style came Scamp (T&TM, 1996), Walker’s first record of all originals* since Driftin’ Way of Life (*counting his arrangement of the traditional “He Was a Friend of Mine.”) They’re not all necessarily his most memorable tunes (well, apart from jingle-catchy “Down in Texas,” which was used in a commercial), but they’re packed with zesty vigor and humor.

After 1994’s self-explanatory Christmas Gonzo Style came Scamp (T&TM, 1996), Walker’s first record of all originals* since Driftin’ Way of Life (*counting his arrangement of the traditional “He Was a Friend of Mine.”) They’re not all necessarily his most memorable tunes (well, apart from jingle-catchy “Down in Texas,” which was used in a commercial), but they’re packed with zesty vigor and humor.  The real keeper is “Let ’Er Go,” in which Walker packs pretty much his entire life story into 7:22 delightful minutes; it’s like a hummable Cliff’s Notes to his Gypsy Songman autobiography. (Walker actually did record a “soundtrack” of sorts to his book: 1999’s Gypsy Songman: A Life in Song, which — just like his similarly titled Tried & True debut in ’86 — was another collection of newly recorded classics.)

The real keeper is “Let ’Er Go,” in which Walker packs pretty much his entire life story into 7:22 delightful minutes; it’s like a hummable Cliff’s Notes to his Gypsy Songman autobiography. (Walker actually did record a “soundtrack” of sorts to his book: 1999’s Gypsy Songman: A Life in Song, which — just like his similarly titled Tried & True debut in ’86 — was another collection of newly recorded classics.)

Cowboy Boots & Bathin’ Suits (T&TM, 1998) is a whole lot better than its admittedly alarming title and cover (Gonzos in shorts!) lets on. Recorded in Walker’s beloved Caribbean get-away of Belize, it’s essentially ¡Viva Terlingua! gone tropical: a part live, part studio postcard from Gonzo Compadre paradise. After Walker gets the requisite steel drums out of his system with the opening “Come Away to Belize with Me,” you’re left with a breezily enjoyable

Cowboy Boots & Bathin’ Suits (T&TM, 1998) is a whole lot better than its admittedly alarming title and cover (Gonzos in shorts!) lets on. Recorded in Walker’s beloved Caribbean get-away of Belize, it’s essentially ¡Viva Terlingua! gone tropical: a part live, part studio postcard from Gonzo Compadre paradise. After Walker gets the requisite steel drums out of his system with the opening “Come Away to Belize with Me,” you’re left with a breezily enjoyable  collection of songs highlighted by Guy Clark’s “Boats to Build” and a terrific Fred Neil medley (featuring “Dolphins,” “A Little Bit of Rain,” and “Everybody’s Talkin’”). Gonzo Stew (T&TM, 2001) is another satisfying offering, mixing can’t-miss covers (Clark’s “The Cape,” Todd Snider’s “Alright Guy,” Roger Miller’s “Dang Me”) with choice Walker originals like the Cajun-spiced “It Don’t Matter,” the Dixie-swinging “Little Old Town Called New Orleans,” and the laugh-out-loud worthy “The Other Jerry Jeff.” Walker also covers two worthy songs penned by his son Django, “Texas on My Mind” and “Down the Road.”

collection of songs highlighted by Guy Clark’s “Boats to Build” and a terrific Fred Neil medley (featuring “Dolphins,” “A Little Bit of Rain,” and “Everybody’s Talkin’”). Gonzo Stew (T&TM, 2001) is another satisfying offering, mixing can’t-miss covers (Clark’s “The Cape,” Todd Snider’s “Alright Guy,” Roger Miller’s “Dang Me”) with choice Walker originals like the Cajun-spiced “It Don’t Matter,” the Dixie-swinging “Little Old Town Called New Orleans,” and the laugh-out-loud worthy “The Other Jerry Jeff.” Walker also covers two worthy songs penned by his son Django, “Texas on My Mind” and “Down the Road.”

Gonzo Stew wasn’t Walker’s last hurrah, but he has since slowed down his recording pace significantly, releasing just two more albums over the course of the last decade. The Mitch Watkins-produced Jerry Jeff Jazz (T&TM, 2003) is Walker’s love letter to the songs he grew up on via his parents’ record collection before setting off to discover his own music. It’s a crooner’s album, but by no means a snoozer; he sounds like he’s having as much fun singing these songs in his 60s as he did singing “Pissin’ in the Wind” in his early 30s. (And for the record, he sounds great singing them, too.)

Gonzo Stew wasn’t Walker’s last hurrah, but he has since slowed down his recording pace significantly, releasing just two more albums over the course of the last decade. The Mitch Watkins-produced Jerry Jeff Jazz (T&TM, 2003) is Walker’s love letter to the songs he grew up on via his parents’ record collection before setting off to discover his own music. It’s a crooner’s album, but by no means a snoozer; he sounds like he’s having as much fun singing these songs in his 60s as he did singing “Pissin’ in the Wind” in his early 30s. (And for the record, he sounds great singing them, too.)  The reflective, laid-back Moon Child (T&TM, 2009), originally released exclusively as a download, is rather sleepy, but Scamp Walker takes his rest with dignity. Every song on the album, from his own “Moon Child” to Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s “Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown” to Chris Wall’s “The Poet is Not in Today” to John Denver’s “Back Home Again,” fits his elder-statesman gypsy songman’s voice tried and true. After 30 albums and five decades of ridin’ high through his driftin’ way of life, the old man’s still doin’ it like he knows it.

The reflective, laid-back Moon Child (T&TM, 2009), originally released exclusively as a download, is rather sleepy, but Scamp Walker takes his rest with dignity. Every song on the album, from his own “Moon Child” to Jimmie Dale Gilmore’s “Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown” to Chris Wall’s “The Poet is Not in Today” to John Denver’s “Back Home Again,” fits his elder-statesman gypsy songman’s voice tried and true. After 30 albums and five decades of ridin’ high through his driftin’ way of life, the old man’s still doin’ it like he knows it.

MR. RECORD MAN’S TOP 5 JERRY JEFF WALKER ALBUMS

1. ¡Viva Terlingua!, MCA, 1973

OK, buckaroos, here’s what you do should you fancy takin’ a chance at makin’ a Texas-sized classic of a country record: Find yourself a tiny Hill Country ghost town, a tub full of sangria, a handful of gonzo compadres, and the blind faith that all the right songs will come along right when you need ’em to. And when in doubt, always remember: It don’t matter how you do it, just do it like you know it.

2. Driftin’ Way of Life, Vanguard, 1969

On the Road, as sung by a young Scamp with nowhere to go but everywhere and no place to call home except wherever his gypsy songman heart fancied.

3. Ridin’ High, MCA, 1975

Released smack in the middle of their unbeatable seven-album run for MCA in the ‘70s, Ridin’ High finds Walker and his Lost Gonzo Band at their pick-up-the-tempo peak. Hold onto your hat for dear life and join the fun — but mind the piss blowing in the wind.

4. A Man Must Carry On, MCA, 1977

Nevermind that CD-era “Vol. 1” and “Vol. 2” nonsense: this is one super-sized collection of classic Walker at his freewheelin’ gonzo best. It’s like the “White Album” of progressive country music.

5. Navajo Rug, Tried & True Music /Rykodisc, 1991

The first great album of his Tried & True era finds independent Jerry Jeff knockin’ on 50’s door but spry as ever, all through throwing good love after bad and ready to click his heels, dance a step and let go a laugh.

I picked up on Jerry Jeff with the release of Viva Terlingua in the summer of 73 in Paleface Park. I have followed him his entire career. One of my fondest memories was when he stopped into Blancos in the mid 90’s to sing a couple of songs for 4-5 of us in the bar. He went missing between sets at the Texas Opry House and found him sleeping in the bed of my truck, circa 1974…To this day I am still friends with Gary Nunn. Texas is not Texas without Jerry Jeff……TheDude..

Thanks from Big Ern in Australia

[…] Jeff thanks everyone. Laughter and applause fill the ‘recording studio’ (said to be inside an old Austin dry cleaners building) with Texans Gary P. Nunn, Bob Livingston, Craig Hills, Michael McGeary, and Herb Steiner (later […]