WILLIE NELSON

Tougher Than Leather

Columbia (1983)

Blessed with a long life, an enduring and distinctly offbeat charisma, and more natural talent than any one man should have, the worst thing you could probably say about Willie Nelson is that he does tend to lean on retreads. Justifiably proud as he may be of a chestnut like “Night Life” or “Funny How Time Slips Away,” one has to wonder how many versions of the same old songs need to be filtered through new producers and approaches every couple of years when Willie offhandedly decides to tackle reggae, swing, blues, (how long until he tries to put the grass back in bluegrass?), Daniel Lanois, or whatever.

But patience is earned. Willie Nelson will always hold the goodwill of country music fans with any sense of adventure because he rolled over the credibility he’d earned from his early contributions to the Great American Songbook and took it upon himself to make waves. Some rough-hewn Austin beer joint could be as noble a stage as the Grand Ole Opry, braids and sneakers could make as indelible an impression as Nudie suits, and a stark song cycle about a roving cowboy grieving deaths that happened at his own hand could sell as many records as a slick package of string-laden love ballads. 1975’s Red Headed Stranger was the landmark, the game-changer, the critic’s choice and left-field success that proved there was more than one way to make successful country music at a given point in history. And it came on the heels of the devastatingly personal Phases & Stages, which was itself preceded by the playfully awesome Shotgun Willie, in a three-year stretch where the humble, twangy Texan seemed like he might be the greatest artist in the world (or at the very least, on one hell of a roll). And maybe it was exhausting, because the tap ran a little dry after that; there was still at least one new Willie album a year for well over a decade, but it wasn’t quite the same. Album-length tributes to Lefty Frizzell and Kris Kristofferson, records built on reinterpreted gospel and pre-war pop, etc. Admittedly, it’s hard not to love Stardust, but one could be forgiven for reaching back for the album that gave the Red Headed Stranger his nickname and cemented his fame.

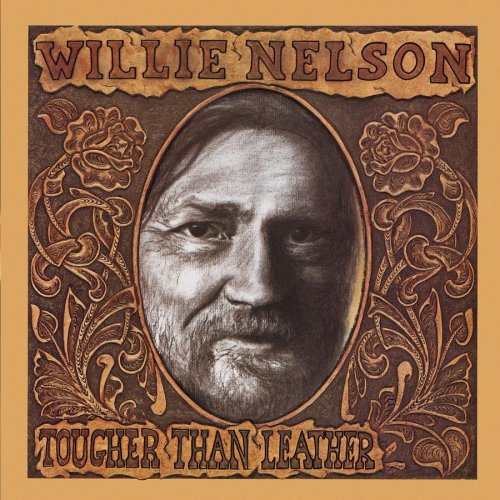

And then out of nowhere, in 1983, Willie did some reaching back himself. If anything, he dug even deeper when he wrote and recorded Tougher Than Leather. It’s historically overshadowed by Red Headed Stranger: it didn’t come first, of course, and it also came at a time when the whole “outlaw country” movement had been absorbed into most listeners’ idea of what modern country music was supposed to be anyway. But the same threads of temporary mayhem and enduring regret are there; there’s interludes of Spanish guitar and barrelhouse piano, reprises of earlier tracks woven in later, and songs of repentance and acceptance tying the whole thing to a bittersweet close. There’s even a sepia-toned photo on the album cover in case anyone missed the point of what Willie and his decade-more-accomplished road band were trying to revitalize.

What’s more, a forgotten note about Red Headed Stranger is that very little of it (including the title track) was written by Nelson himself. His genius lay in tying together traditional material into a tale of his own design. By the time he got around to Tougher Than Leather, maybe he’d exhausted his interest in other people’s material; the sounds and themes might have been older than the hills, but the words were his own. The knockout title track features an aging drifter who takes down an upstart cowboy in a gunfight (to be fair, the kid started it) then finds the rest of his life tainted by self-recrimination over the grief he caused the young man’s sweetheart. It’s pretty amazingly self-contained, but as on Stranger, Nelson found worlds’ worth of emotional weight both in the lead-up and the long denouement. “Little Old Fashioned Karma” dabbles in the sort of other-world spirituality that’s usually literally foreign to country music; “Changing Skies” and “I Am the Forest” tap into the trippy, transformative, ominous powers of death and change and redemption with depth and world-weary tunefulness. Narrative concept albums weren’t really in style by 1983, even for ambitious rock bands, but Nelson’s force of personality was a binding strength and a compelling voice that made it soar. “Flying high, flying high … from a place to a place … changing skies, changing skies.”

It’s a feast of an album, a somewhat obscure high-water mark in an outstanding career, and yet in many ways one of those gems that somehow sink towards the bottom of the deep bin of Willie Nelson albums. May we all be so lucky as to do enough great things that something this good could be overlooked. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment