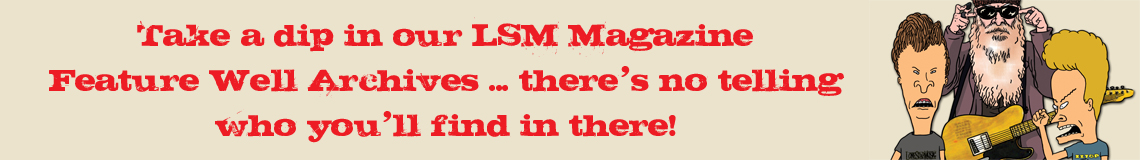

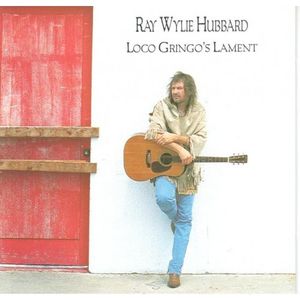

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD

Loco Gringo’s Lament

Dejadisc (original)/Misery Loves Company/Smith Entertainment (reissues)

Most folks have heard the F. Scott Fitzgerald quote about how “there are no second acts in American lives.” Not especially accurate, one could easily argue, but then again this quote’s from 1932 and that’s before the modern music business really kicked in. Since then, redemptions, resurgences and reinventions are normal and often necessary: in a way, Ray Wylie Hubbard checked all three boxes, with the still-stunning 1994 album Loco Gringo’s Lament as the centerpiece of his turning point.

Hubbard might have gone down as a footnote in the long shadow of the Willie Nelson-spearheaded “outlaw country” movement of the mid-70s if he hadn’t penned one of the era’s crucial anthems, “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother.” A good-natured bit of satire Trojan-horsed into a raucous beer joint sing-along, it found its way onto popular records by folks like David Allan Coe and Jerry Jeff Walker and became a bar-band standard for the decades to come. And though it was more clever and substantial than some folks gave it credit for, it wasn’t overly representative of its writer. Unfortunately for Hubbard, neither was his 1975 debut album (Ray Wylie Hubbard & the Cowboy Twinkies); he’s gone on record with how much he disliked the post-production tweaks and add-ons, and he had no interest in promoting the finished product. Despite his reputation as a raucous live act and a unique songwriter, he was a bit of an obscurity even on outlaw-friendly turf, and substance abuse issues were nudging him even further adrift.

Not too far adrift, though, for a second act. Hubbard’s problems were nothing that a resolute commitment to sobriety, a happily enduring marriage, a few rounds of mid-life guitar lessons and a thorough rediscovery of his gifts as a songwriter couldn’t fix. Near-forgotten outside of his fellow songwriters and a few diehard fans, Hubbard rehabilitated his career with the same panache with which he’d turned his personal life around. For his fans, Loco Gringo’s Lament will always be a sentimental turning point, but to the uninitiated it still stands as a damn fine album on its own terms.

The comeback started in 1992 with Lost Train of Thought, a solid album with more than a few memorable songs that got his rejuvenated soul back on the road and set the stage for a greater triumph. His timing wasn’t half bad, either: younger Texans were gradually getting on board with the idea of homegrown alternatives to modern country music, thanks to folks like Robert Earl Keen, so the interest in a Ray Wylie Hubbard comeback expanded past the outlaw-country holdouts into the new generation. And Loco Gringo’s Lament delivered in spades, sparking critical acclaim and nudging Hubbard from near-forgotten to a reclaimed legend of sorts. We couldn’t have known it at the time, but it also put him on track to being one of modern Americana music’s most prolific, distinctive, and successful artists.

But enough about context: how about the album itself? Hubbard boldly kicked off with the baleful, ominous “Dust of the Chase,” five minutes of finger-picked gunfighter ethos tackling mayhem, sex, prayer and restlessness with stoic, unhurried grit. The tempo picked up gradually (and the mood lightened considerably) with the one-two punch of “Just to Hold You” and “Love Never Dies,” two modern love songs awash in gratitude, detail and vulnerability. “We can take nothing greater, on our journey/And rest assured, we need take nothing less” remains one of the great assertions of modern songwriting, and yes some of us might be a little biased because we loved that song enough to make it the first dance at our wedding.

From there, even more up-tempo positivity takes over for a while, with the grooving “Little Angel Comes a Walkin’” and the more philosophical “After the Fall” before the band veers hard into the still-striking “Wanna Rock & Roll.” Partly disguised by the generic title, it’s a taut, biting racecar ride through juke joint romance, backseat sex, public infidelity, and straight-up murder. If the aforementioned love songs were the heart of the album, this was the ornery flipside that hinted at the darker, bluesier tones that would eventually dominate Hubbard’s output.

“Wanna Rock & Roll” also exhausted the record’s supply of havoc (there’d be plenty more on future albums), giving way to a thread of literate compassion that never quite lets up. “Bless the Hearts of the Lonely” is as kind and straightforward as its title implies; “Loco Gringo’s Lament” casts a cautionary light on the rock ’n’ roll excesses that cost Hubbard a lot of years (and of course could have cost him much more); and with “The Real Trick,” Hubbard extends some righteous empathy to the exploited souls of the world and rails against “beautiful ancient wisdom prostituted for personal gain,” tipping his hat towards the teachings of Jesus with one hand while smacking down greedy evangelists with the other. Beautiful, stirring stuff, but somehow it all sets the stage for the even grander “The Messenger.” Probably Hubbard’s greatest composition at the time, and arguably still his best, it’s a sweeter bookend to the album’s stark “Dust of the Chase” opener. “I have a mission, and a small code of honor/To stand and deliver by whatever measures/And the message I carry is by Rainer Maria Rilke/Our fears are like dragons guarding our most precious treasures …”

It was a stunning, personal statement of purpose that still made the time to quote and name-check his favorite poet. Since then Hubbard’s name-checked everyone from Muddy Waters to William Blake to Jon Dee Graham, and when you hear his own name dropped reverently in song by everyone from Houston Marchmann to Hayes Carll to Eric Church, Loco Gringo’s Lament is no small part of the reason. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment