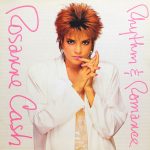

By Holly Gleason

Thirty years ago, at a time when Nashville was running on the fumes of Merle, Waylon, Willie, and Emmy, the general state of country music was young(ish) women who were the doppelgangers for late middle-aged secretaries with functioning libido, lounge-lizard lotharios with back-combed chest hair, good ole boys left over from the Urban Cowboy era, and vocal groups that were more gospel harmony than the Everyman bar band Alabama. The industry was booming, with country having grown into the most listened-to genre in America, but it had also grown soft, with almost all traces of honky-tonk grit, hardscrabble truth and outlaw swagger washed clean away in the mainstream. Less than a decade after Wanted: The Outlaws gave country its first platinum album, the status quo had over-corrected and moved over to “Islands in the Stream.”

It was time to rock the boat again. And at least for a spell, that’s just what a handful of intrepid artists did, rising from the ashes of what country meant and breaking through the wall of vanilla white noise to bring the music back to where it really came from. A young and restless Steve Earle, still years if not decades away from bona fide Americana icon status, took Merle Haggard’s “Every Working Man” reality and grafted it onto a populist rock frame. Dwight Yoakam took the jack-hammered intensity of L.A. punk and applied it to hardcore classic country. And Rodney Crowell offered a cooler, New Wave edge to Emmylou Harris’ hippie traditionalist Laurel Canyon country cousin to the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and Poco.

Earle, Yoakam, and Crowell weren’t alone, either. Whether it was the Desert Rose Band’s Bakersfield/bluegrass hybrid, Foster & Lloyd’s rockabilly/Texas shuffles, or the Blaster’s Dave Alvin’s stark Steinbeck drifter ’n’ loser take on Haggard, the music came from varied places and mined different approaches and aesthetics, but it all felt deeply rooted in meaningful ways to country’s antecedents while simultaneously pushing the genre forward in new and interesting ways. Most thrilling of all, though, was the fact that so much of these mavericks managed to be heard not just on the fringes, but smack in the middle of that mainstream — not as part of an easily defined and industry co-opted and packaged “movement” so much as rogue agents infiltrating the machine. Fittingly, it was Earle himself who later summed up the phenomeon best: He called it “The Great Credibility Scare of the ’80s.”

It wouldn’t last for very long, but it’s impact was profound. In some ways, the Credibility Scare made Nashville safe for staunch traditionalists ranging from Randy Travis, Ricky Skaggs and Keith Whitley to more mainstream classicists including enduring icons George Strait and Reba McEntire, as well as the now defunct Judds. And for a few unforgettable years, country seemed like it really could be the smartest genre in contemporary music. With spark, pop, heart, and rural soul, the Credibility Scare brigade transfixed critics, music aficionados and plenty of country fans looking for something a bit more real. These are some of the records that helped light the fuse and gave us a reason to believe.

* * *

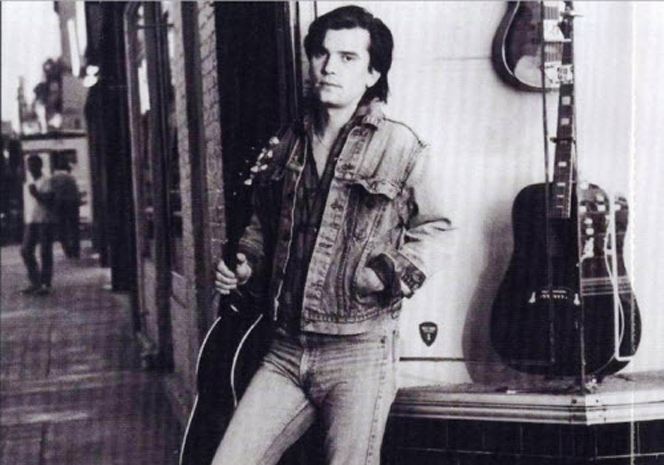

Steve Earle, Guitar Town (1986)

Hard-charging, blue-collar hippie redneck Steve Earle told the truth about the Southern working poor with Richard Bennett’s resonant electric guitars, hard down-stroked acoustic creating a populist surge, and just enough pedal steel to let you know “this ain’t Springsteen.” But like the Boss, Earle’s tales of long-haul truckers, all-night gas station attendants and ne’er do well musicians rang with authenticity from the margins.

Dwight Yoakam, Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. (1986)

Although Kentucky-native-turned-L.A. denizen Dwight Yoakam has always worn his “hillbilly” music roots proud, his major-label debut was anything but an exercise in antiquated ’50s and ’60s country jukebox nostalgia. Whether giving Johnny Horton’s “Honky Tonk Man” a baleful moan or injecting an electric edge into the title track’s iconic checklist of post-honky-tonk living, Yoakam brought an exhilarating swagger to the genre that was all his own. Between Yoakam’s chilling howl, the punk crash of the drums and Detroit bluesman/producer Pete Anderson shoving the guitars way up, Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc. conjured a sexiness that was as much an homage to cowpunks Exene Cervenka and John Doe of X as it was to Hank Sr. and Buck Owens.

Rosanne Cash, Rhythm & Romance (1985)

With 1981’s Seven Year Ache, Rosanne Cash toppled the notion of genre exclusivity by embracing songs by Steve Forbert and Tom Petty as well as Merle Haggard. But the snap of the drums and the languishing of the rhythm section suggested country was looking at a punk gutting of the bloated MOR-ery that had settled on the genre. Rhythm & Romance made good on the promise. If the sheets of synthesizer sound dated, they represented the curves of the new wave — and the frenzy of John Hiatt’s “Pink Bedroom” exploded country’s post-modern spark. There were soul-searching moments — the raw “Halfway House,” the aching “My Old Man” — but also a sense that country could shed its bloat and return to its essence harder than ever.

Lyle Lovett, Lyle Lovett (1986)

A collection of demos polished into final mixes by Tony Brown, Lyle Lovett’s self-titled debut brought a high literary sensibility and down-home set of metaphors to the human condition. A quirky mix — from Tammy Wynette worthy ballads (“God Will”) to romp ’n’ ride gusto (“Cowboy Man”) — the album was unified by the dusty romantic prism that Lovett drew his vignettes and portraits from. A little swing, a little Guy Clark, a bit of the old cowboy matinees, he showed the life of a dreamer a little short on the rent and high on the dream, delivered in a voice like dry oak tempered by a wink when it’s necessary.

k.d. lang, Angel with a Lariat (1987)

Canadian k.d. lang hit Nashville like an 18-wheeler through a nursery school window. Never mind the flattop haircut, chain-sawed cowboy boots and almost cartoon cowgirl clothes; that voice — dark and dusky and all mellow erotica and musk — and that control suggested the manifest of Patsy Cline’s legacy. The bouncing take on Lynn Anderson’s “Rose Garden,” as much jovial polka as anything, was the nudge that suggested the old school had value. The earnest come-on implied the erotic charge was real. And was it! kathy dawn lang was a singer’s singer — whether joking through “Got the Bull By the Horns” or laying waste to the heart with her take on Cline’s “Three Cigarettes in the Ash Tray” — and she understood irony and ecstasy as a diving rod to a song’s true center.

Dave Alvin, Romeo’s Escape (1987)

The Blasters, like X and to an extent Los Lobos, understood the urgency underlying American roots music, and they paved the way in many ways for the Credibility Scare. When Dave Alvin left the blues/rockabilly-leaning band for a solo career, he drifted to Nashville where his terse lyrical pictures captured the same kinds of jagged moments that electrified the underbelly of Bakersfield’s oil field communities. More austere than Yoakam, who would have a No. 1 with the haunted “Long White Cadillac,” Alvin tore through the punk rage of “New Tattoo,” the American Dream’s smothering ennui on “4th of July,” and the lonesome culture blur of “Border Radio” with a tone that was almost holy. These weren’t contrived scenes, but lives lived till threadbare. And like Haggard, he gave the less-thans swagger, dignity and a realism that honored the truth, not some Hallmark take on Steinbeck.

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Vol. 2 (1989)

The first Will the Circle Be Unbroken, released in 1972, saw the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band as hippie kids trying to unite old-guard country stars — from Roy Acuff and Maybelle Carter to Jimmy Martin — with the counter culture. In 1986, the California/Colorado pop/rock/country/jug band took the old-guard in Johnny Cash, Acuff and Martin, brought in Cred Scare kids via Foster & Lloyd and Ricky Skaggs, outliers including Bruce Hornsby, and merged their own peers John Prine, Chris Hillman, and Roger McGuinn for a core sample of a moment of true musical merging. Recorded live at (Randy) Scruggs Sound, the tracks bristle with the combustion of great players pressing each other. Rosanne Cash and John Hiatt’s “One Step Over the Line” is a naughty romp that’s as erotic as it is fun, while Emmylou Harris’ bittersweet “Mary Danced with Soldiers” and Levon Helm’s “When I Get My Rewards” both demonstrated the elegance of acoustic music given room to breathe. To sink into this forgotten jewel is to truly understand the moment — and the NGDB’s role as curators long before the term was vogue.

Rodney Crowell, Diamonds & Dirt (1988)

Rodney Crowell, long a critics’ favorite, teamed with old friend Tony Brown (with whom he’d played in Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band) to make an album that represented the best of every kind of country music he’d heard growing up in Houston. Beyond a cover of Buck Owens’ “Above and Beyond,” sung with an almost hummingbird sweetness, there was the twin fiddle “I Couldn’t Leave You If I Tried,” the juke jointin’ “Crazy Baby,” the almost Elvis balladery of “After All This Time” and Guy Clark’s loping “She’s Crazy for Leavin’.” If any one album defines the overlap between the new traditionalism emerging and the credibility scaremongers, this is it. Classically approaching the genre, Crowell offers takes on the forms that throw the windows open and breathe an easy reality into them. Sexy without being overt, smart without straining, shuffling without counting the beats, this made real country fun for the naysayers and non-believers. And boy, did it pay off: Diamonds & Dirt was the first country album to have five No. 1 hits.

Emmylou Harris, The Ballad of Sally Rose (1985)

At the time of its release, whispers abounded that this tragic song cycle was the fictionalization of Emmylou Harris’ artistic entanglement with the late Gram Parsons, self-proclaimed purveyor of “Cosmic American Music.” Whether it is or it isn’t, The Ballad of Sally Rose is an honest, post-feminist portrayal of a woman facing heartbreak, finding purpose in the music and carrying on with dignity in the devastation. It’s also home to the exquisite “Woman Walk the Line,” a stately paean to the girls who go into the night seeking songs, not paramours.

Foster and Lloyd, Foster and Lloyd (1987)

If the Byrds and the Beatles had a slumber party at the Everly Brothers’ house and listened to nothing but Hank Williams records, the result would be not unlike Foster and Lloyd. Del Rio, Texas’ Radney Foster teamed with Bowling Green, Kentucky’s Bill Lloyd for a slightly hip duo that merged a disarming air of innocence with the college radio tilt of the BoDeans, the dBs (whose “White Train” they covered), and the Blasters. Foster’s voice, wide open and warm, captured the unrequited guy’s ache in “You Can Come Crying to Me,” the black-and-white valor of the local rodeo celebration “Texas in 1880” and the unabashed crush of the industrial rockabilly shuffle “Crazy Over You.” But it’s Bill Lloyd’s jangle guitars and sense of melody — and those irresistible, sweeping harmonies — that set F&L apart from all other duos, making them retro post-modern charmers.

The Desert Rose Band, The Desert Rose Band (1987)

Though best known as the country-leaning member of the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers, Chris Hillman’s true roots were in the Golden State bluegrassers the Hillmen, which also featured hard country legend Vern Gosdin. Creating a supergroup with superstar harmony singer/bluegrass vet Herb Pederson and wunderkind guitarist John Jorgenson — as well as iconic steel player Jay Dee Maness, Palomino Club drummer Steve Duncan and upright bass bluegrasser Bill Bryson — The Desert Rose Band was aggressively acoustic, muscular and propelled by a euphoric cover of Johnny & Jack’s “Ashes of Love.” But just as importantly, Hillman & Co. stirred history into a more aggressive kind of pure country. “One Step Forward” gave the band another hit, as did their melancholy “He’s Back and I’m Blue,” their first No. 1. Jorgenson’s guitars — electric and otherwise — pushed Nashville into a rock vein that never lost its California country footing.

Lone Justice, Lone Justice (1985)

Comprised of three L.A. kids (singer Maria McKee, guitarist Ryan Hedgecock, and bassist Marvin Etzioni) with an ear for unfiltered rock and throwback country and one veteran from Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band (drummer Don Heffington), Lone Justice was a firebomb in roots country clothing with enough blast to help launch cowpunk with their self-titled 1985 debut. Tom Petty and Mike Campbell provided the churning “Ways To Be Wicked,” while professed Christian McKee’s gospel exhortations on “Soap, Soup and Salvation” and her ecstatic delivery on Etzioni’s “You Are the Light” suggested the redemption after Saturday night. Balancing the threatening swagger of “Wait Til We Get Home,” which bristled with erogenous charge, with the inconsolable throb of “Don’t Toss Us Away” (penned by McKee’s brother, Bryan MacLean of ’60s psych-folk rockers Love, and later a hit single for Patty Loveless), Lone Justice swung the emotional gamut. Alas, critical acclaim and accolades from the the likes of Yoakam, Dolly Parton and even U2 never quite translated to commercial success, and the band wasn’t built to last; they’d disband shortly after the release of their second album, Shelter, in ’86. But their exhilarating command of roots music’s most extreme and palpable passions blazed a trail for the next generation of alt-country frontiersmen and women.

As usual, spot on girl!

This is tremendous insight and I am happy to say I own most of those records…

It was a breath of fresh air in the early eighties when Steve Earle et al hit … kinda like when the Beatles kicked rock n rolls tamed ass back in the sixties, and IMHO we need another big boot now !

Great article.

You followed them all, all along, didn’t you! Kept us up on it all. We still need this list! Thanks Holly! You deserve a new pair of shoes!