By Andrew Dansby

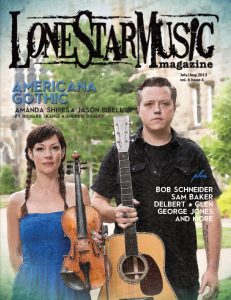

(LSM July/Aug 2013/Vol. 6 – Issue 4)

Six years ago Jason Isbell had a new band and a new career, and he spoke with conspiratorial candor about both, recalling a sunny morning a few days earlier in what he called “picturesque Madison, Wis.” Isbell and the 400 Unit had played a show there the night before and were feeling the effects of a late one. Right as their van slowly passed in front of little open-air market, one of the band members flung open the side door and issued a stream of vomit, right in front of an unsuspecting audience of stroller-pushing families. The rest of the band, meanwhile, had to decide whether it was worth spilling their coffee to try and grab their mate’s belt and keep him from falling out of the vehicle.

Things have changed for Isbell since then. Once best known for his short but noteworthy stint as a Drive-by Trucker, he is now an acclaimed solo artist with six albums (two of them live) under his belt and a growing Americana audience for his soulful sort of narrative rock ’n’ roll. His latest studio album, Southeastern, has already netted him a feature in the New York Times, while his previous one, 2011’s Here We Rest, produced “Alabama Pines,” which won Song of the Year at the Americana Music Association’s Honors and Awards ceremony last year. At 34, Isbell is also newly sober. Talking from his Nashville apartment, he speaks in a soft tone and foregoes the stories of drunken tour shenanigans in favor of measured, thoughtful answers that suggest a newfound clarity about where he’s been and where he is.

There’s a lot of movement on Southeastern, which plays out as a series of meditations on home and self. Isbell has always written with an intense awareness of place. Graveyards are never just graveyards — they always have names. So do streets, stores and some towns he’s been to that you likely haven’t. As a musician, Isbell’s home on any given night is often far from the place where he receives his mail, so it’s logical that such a transient existence could lead to the contemplation of life, death and identity and how they relate to one’s home.

Especially identity. The talented big kid who hid behind a ball cap, a bottle of whiskey and two other singer-songwriter/guitarists in the Drive-by Truckers isn’t the same one who recorded this new set of songs. Southeastern has a now-and-then construct of a guy singing about his former self. “There’s a man who walks beside me, he is who I used to be,” Isbell sings on “Live Oak.” On “Songs that She Sang in the Shower,” he sings from the point of view of a character who says, “In a room by myself/looks like I’m here with the guy that I judge worse than anyone else.” Elsewhere, there are signs of change: “The difference with me is I used to not care,” goes one line. In the song “Elephant,” one character tells another, “You’re better than your past.”

Especially identity. The talented big kid who hid behind a ball cap, a bottle of whiskey and two other singer-songwriter/guitarists in the Drive-by Truckers isn’t the same one who recorded this new set of songs. Southeastern has a now-and-then construct of a guy singing about his former self. “There’s a man who walks beside me, he is who I used to be,” Isbell sings on “Live Oak.” On “Songs that She Sang in the Shower,” he sings from the point of view of a character who says, “In a room by myself/looks like I’m here with the guy that I judge worse than anyone else.” Elsewhere, there are signs of change: “The difference with me is I used to not care,” goes one line. In the song “Elephant,” one character tells another, “You’re better than your past.”

Although Isbell characterizes Southeastern as being “very personal without necessarily being autobiographical,” every song sounds lived in and informed by first-hand bad experiences. Alcohol and drugs and fights appear and reappear in the stories throughout, and at times hope seems to be but a light in the rearview. But new towns provide new brightness. And like a bird flying south to escape the cold, Isbell seems to have found his own migratory pattern to get away from the discomfort referenced in so much of his writing. He headed southeast and made his best album so far in a career and life that now has renewed clarity and purpose.

***

Isbell opens Southeastern with “Cover Me Up,” a song that references past trials from the perspective of the warm and reassuring succor of redemptive love — and the clarity of sobriety. It’s no secret that the person leaving her boots by the bed is Amanda Shires, the esteemed singer-songwriter and fiddler player who is now his wife.

They started as friends and collaborators and competitive pool players.

“He’s pretty good at pool,” she told me two years ago. “But all I have to do is get him drunk, then I can whoop his ass.”

Shires referenced a $20 debt from a pool game, so it didn’t seem she was going to get rich taking advantage of her friend. As they grew closer, she instead staged an intervention.

“I felt, if not unique, then alienated in that I felt there were these joys or things that make people happy in life that weren’t really in the cards for me,” says Isbell, post rehab. “I felt clouded in a way, and that prevented me from realizing that wasn’t the case. That’s the cycle. You drink because you don’t think you can be happy sober. And you can never be happy sober, because you’re always drunk.”

He laughs.

“I was fortunate to find some humility that wasn’t there before,” he continues. “Almost everybody in the world has it a whole hell of a lot worse than I do. Even if I never fell completely in love and got married, even if I drank myself to death at 35, that still puts me light years ahead of 99.9999 percent of people who ever lived on earth. When you come to terms with that, it all falls away.”

Southeastern isn’t a concept album, but the sequencing does unspool in a narrative fashion. “Cover Me Up” has the most direct connection to Isbell today, offering a glimpse of the present before telling the story as to how one arrived there. It’s almost cinematic in a way, though Isbell stops the comparison to specify, “well, the way cinema used to be.”

“Now, everybody’s so concerted with action,” he explains. “Even in narrative pictures and albums, everybody is so concerned with hitting you in the face first. People are worried about selling the first song in a show. But in all honesty there’s no reason to punch them in the face off the bat. Work toward a goal.”

He points to his wife as a positive example of the later approach, noting that Shires sometimes starts her performances with an a capella song. And “Cover Me Up,” though far from being that spare, likewise opens Southeastern on a note of quiet but assured confidence, promise, and hope.

“This just seemed to me a good way to start the album,” says Isbell. “In a lot of ways it’s a summary of where I am now. If a record is a record of events, why not start there? Why not start somewhere good?”

***

Later on Southeastern, though, good turns to fatigue. There’s a plea for company, and some prickly tales of people struggling through their nights.

Years ago, during the interview with the aforementioned band-member-puking-out-of-the-van story, Isbell discussed his then-new album Sirens of the Ditch, his first outing after being forced out of the Truckers. The title referred to frogs, a phrase written by 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. At the end of a tour Isbell said he bought a frog, thinking it might be the sort of pet he could maintain. “I don’t have the capacity to take care of anything except myself,” he said.

Years ago, during the interview with the aforementioned band-member-puking-out-of-the-van story, Isbell discussed his then-new album Sirens of the Ditch, his first outing after being forced out of the Truckers. The title referred to frogs, a phrase written by 16th-century Italian poet Torquato Tasso. At the end of a tour Isbell said he bought a frog, thinking it might be the sort of pet he could maintain. “I don’t have the capacity to take care of anything except myself,” he said.

It turns out Isbell’s capacity for self-preservation was overstated. A bottle of whiskey always seemed to be within arm’s reach when he was onstage with the Truckers. After Isbell joined the group, the Truckers’ dynamic seemed hard-wired for sparks. For starters, he joined a band on the rise, after the Truckers had garnered national attention for the album Southern Rock Opera. The Truckers didn’t look like a band of equals: Despite the weariness in his voice and the seasoned nature of his songs, Isbell was only 22 when he joined the band, visibly much younger than Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley, who had started the Truckers years earlier.

Then there’s the natural toxicity that comes from three creative types contributing songs. It seemed copacetic at first — Isbell’s incendiary song “Decoration Day” was the title track of his first album with the band. His “Goddamn Lonely Love” and “Danko/Manuel” were also standouts. But the shows eventually exuded a palpable tension, particularly noticeable on stops during their 2006 run opening for the Black Crowes. Further complicating matters was the fact that Isbell’s marriage at the time — to Truckers bassist Shonna Tucker — was coming undone.

Then there’s the natural toxicity that comes from three creative types contributing songs. It seemed copacetic at first — Isbell’s incendiary song “Decoration Day” was the title track of his first album with the band. His “Goddamn Lonely Love” and “Danko/Manuel” were also standouts. But the shows eventually exuded a palpable tension, particularly noticeable on stops during their 2006 run opening for the Black Crowes. Further complicating matters was the fact that Isbell’s marriage at the time — to Truckers bassist Shonna Tucker — was coming undone.

Alcohol couldn’t have helped matters.

“We were all just really fucked up for the most part,” he says. “We were a bunch of really heavy drinkers. It’s not my place to say if somebody else is an alcoholic or not. We all did our share. We were just a bunch of rednecks given a little bit of money, which is not necessarily a great thing.”

But Isbell’s departure from the band did nothing to stop the flow of whiskey.

His dismissal was broken to the public in the muted clichés of the music industry, with the requisite language about creative differences and growing apart. And Hood, who issued the statement about it, produced Sirens of the Ditch, which furthered the impression that things were OK. Nobody believed that, though. But it wasn’t until only recently that both parties finally came clean with the admission that Isbell was fired.

By then, both Isbell and the reconfigured Truckers had already moved past the issue and realized that they were better for the split. Still, it’s easy to see how the dismissal could’ve shaken the young writer, whose identity at the time was so linked with a band whose identity, like his own, was rooted in the South.

***

Isbell’s ease with detail in his songwriting is part study and part experience. He grew up in Greenhill, Ala., the son of a house painter. Music was never far away. Muscle Shoals, an epicenter for Southern soul, was a short drive away. There was musical appreciation in the family, though Isbell says they were laborers rather than songwriters.

Isbell got his first guitar before he was 10, and thinks he started writing around 13. Because of his size and his family’s work, labor was always around the corner. His father once made him load trucks at a fireworks factory to pay him back for bailing him out of jail. He ended up six hours short of graduating from the University of Memphis, eventually continuing his studies with the Truckers.

But Greenhill and his family were never far from the surface in his work. One of Isbell’s first songs to draw notice was “Outfit,” in which a house painter father offers advice to his musician son. Isbell’s father’s work is where he found the title for his new album, too: it was the name of a paint manufacturing company where the old man worked.

“I remember the place being sort of a dungeon in my mind,” Isbell says. “There would be folks getting injured on the job. I remember a guy got a piece of metal in his eye from one of the dye machines. Instead of making a workman’s comp claim, the foreman would just hold his eye open and take a credit card and run it against his eyeball until the metal came out. As a kid that’s horrifying. So I guess it was sort of reclaiming a piece of my past that was a little bit frightening.

“These are all work songs, in a lot of ways,” he continues, “whether they’re physical work songs or about doing work on yourself — on your own personality and your own character.”

After the hopeful opening, the idea of home feels elusive on Southeastern. Travel takes characters to places that become song titles — “Stockholm” and “New South Wales” — both places found in the southeastern region of their respective countries, and both of them very far from the Southeast he knows. Characters are often detached from family and friends, often due to drink or drugs. One is dying, presumably of cancer, and he notes, “surrounded by her family, I saw that she was dying alone.”

Isbell is a voracious reader and a precisionist with language. He also seems to have a keen affinity for the way names of pharmaceuticals sound, like benzodiazepine and Klonopin. The former is used in Southeastern’s “Different Days,” and the latter in “Relatively Easy.” (His last album, meanwhile, featured a beautifully melancholy song called “Codeine.”)

“I just think they’re very interesting words,” he says. “And I felt like they fit. I didn’t have to search for those words. But I never really took prescription drugs like other people have. They’d usually halt my drinking abilities, which didn’t need much help in hindsight. But I know which ones you can’t mix together. That’s Band 101: Knowing what not to take, what you can’t do a lot of … If you don’t learn that you end up one of those people that falls asleep on a couch and doesn’t wake up.”

Fortunately for Isbell, he shook his addiction to his own drug of choice, alcohol, before it came to that. But sobriety, too, factors into the anxiety of identity threaded through these songs. After the chemical fog burns off, what remains? Relationships and daily habits defined by drinking are no longer the same. Does a new person rise from this?

“I don’t mean this in a negative way, but it’s really like a math problem,” Isbell says. “Things need to be solved. In some cases it’s this transition between a prolonged childhood and acceptance of adult-hood. That really is at the heart of what’s been on my mind the past couple of years. In my 20s, I was trying to behave like a teenager and pulling it off for the most part. I didn’t have to grow up until I was ready to. As that’s happening, you’re looking at what goes in red and what goes in black. It’s not quite a balance sheet, but I feel like I gained more than I lost.

“I’d be lying if I said it was all for the better, though,” he continues. “There are still things you miss, and I wouldn’t call them regrets. I’m glad they’re where they are, that I was that person at that point in time. But I’m also glad I’m not that person anymore. Trust me, in this particular business there are a lot of people who never make the decision to be an adult. Sometimes that decision gets made for them at 27, at 32, at 45.”

He says he’s seen too many musicians and songwriters — heroes and mentors — who “are just a shell of who they were,” even though they’re not that old.

Isbell admits that he’s “not a big AA guy.” “I’m not really into meetings and I don’t care for their politics,” he explains. But he does say that the Serenity Prayer has been crucial to recovery.

“You have to come to terms with the fact that there are things you can’t fix,” he says. “I’ve become a person who looks at situations from this point forward and thinks, ‘Whatever happened yesterday is done. Here’s where we are right now and how we go about fixing it. The first part is trying not to worry so much about who to blame.”

***

Yesterday is done, then, and here’s where Isbell is right now: sharing a comfortable coexistence in Nashville with Shires, who formally became Amanda Isbell in February when their friend and fellow singer-songwriter Todd Snider officiated their wedding in Nashville. Snider got himself ordained at Shires’ request.

“It was his first wedding, and he makes a great reverend, but he said he’s only going to do non-heterosexual weddings from now on,” laughs Shires, who along with Isbell played on Snider’s Agnostic Hymns & Stoner Fables album.

“I was honored to be asked, to be sincere,” says Snider. “It was really pretty, and she looked beautiful, of course.”

Isbell talks about wanting to start a family, though that may be a ways off still, with new his and hers albums to promote (Shires’ latest, Down Fell the Doves, is due Aug. 6.) In the meantime, there’s already plenty of creative cross-pollination between the two. They play on each other’s records, frequently tour together and support each other onstage. And back home, they write together — in a fashion, at least. Isbell admits that they’ve only co-written one or two songs together (“That’s not easy for either of us,” he explains). But they’ve worked out a system where they retreat to opposite sides of their apartment to write on their own, then convene in the middle.

“That part has worked real well so far,” says Isbell. “We help each other edit. And it’s great, because in general, anybody who’s unafraid to tell you when you’re being a jackass can help you bring a song into the world. It’s really beneficial. But a lot of people push those people out of their life.”

Snider observes that Isbell and Shires should be careful, though, because “they’ve both made monster records. I could see them battling each other for trophies next year.”

He laughs, but he’s not kidding about his respect for both of them.

“Amanda and Jason and Hayes (Carll) and Justin Townes (Earle), that whole generation of players are really strong,” Snider says. “I find them inspiring. It’s a fun group to be around. They make me feel older, but I don’t mind — that’s an easier chair to sit in that the one they’re in. I love listening to these younger people who are just going mad, and Jason and Amanda definitely are that. They have given the entirety of themselves to this.”

For Isbell, that’s proven to be even more true with sobriety. He was always committed to his craft, but now finds he has a lot more time to write.

“If you’re spending six or eight hours drinking, go to sleep, then spend two or three hours with a hangover, there’s not really much day left.”

Southeastern closes, as it opens, with a song that feels particularly personal. It’s one that came out of one of those show-me-yours-and-I’ll-show-you-mine sessions with his wife. In the song, the narrator’s “angry heart beats relatively easy,” a line that tempers its tension with hope. It also echoes the first line on the album: “A heart on the run keeps a hand on the gun/you can’t trust anyone.”

Unlike the case with “Cover Me Up,” though, the narrator in “Relatively Easy” isn’t necessarily Isbell himself. But they do share the same heart, and with it the same longing for some inner peace and trust. And each in their own ways, they find it.

“I should say I keep your picture with me every day

The evenings now are relatively easy.

And here with you there’s always

something to look forward to

My lonely heart beats relatively easy.”

***

RELATED

How can I getalk a physical copy of this issue?

The magazines we still have in stock (and at the moment we still have copies of the Jason Isbell/Amanda Shires issue) can be purchased here: https://www.lonestarmusic.com/index.php?file=mer-merchandise&iCategoryId=10