By Richard Skanse

(LSM July/Aug 2013/Vol. 6 – Issue 4)

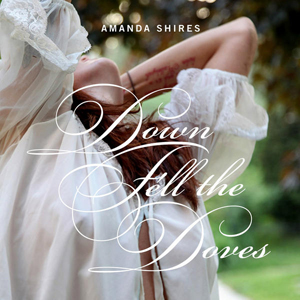

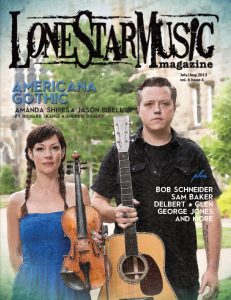

On Feb. 23, 10 days before her 31st birthday, Amanda Shires married fellow singer-songwriter Jason Isbell in a Nashville ceremony officiated by their friend, Todd Snider. On Aug. 6, Lightning Rods Records will release Down Fell the Doves, the follow-up to Carrying Lightning — Shires’ strikingly confident, self-released 2011 album that staked her claim on the Americana map as one of the genre’s most critically adored and buzzed-about young artists in recent memory (culminating with Texas Music magazine crowning her as its 2011 Artist of the Year.) So how did Shires spend the bulk of the long, hot summer of what she’s sure to remember as one of the most monumental years of both her personal life and career?

Studying her ass off and mainlining caffeine to get through summer school.

“Joyce research paper due in the a.m. … I’m screwed,” she groans via text message on the evening of June 27, after I ping her with a quick follow-up question to the interview we’d had three weeks prior. Her topic: “700 Allusions to Music in Ulysses.”

A couple of days later, a check up confirms that she survived the ordeal … more or less. “I bet I did well first few pages,” she specualates optimistically, “then dive into crap land.”

There are innumerable less stressful ways for a promising young artist (and newlywed) to spend a two-month breather from constant touring in advance of launching a new record — not to mention a handful of breezier summer reading picks than James Joyces’ notoriously enigmatic doorstopper. But it’s hard to feel too sorry for Shires, because of course nobody makes a self-reliant, grown woman already well on her way to a successful independent music career carve out time to pursue a Master of Fine Arts in poetry. Shires, who’s still paying off her student loans for her undergrad degree in geography from Texas Tech, applied to the University of the South’s Sewanee School of Letters in 2011 out of her own volition.

“I just wanted to learn more about words and writing so I could hopefully get some more tools in the toolbox to write better songs,” says Shires, who started her third year of the four-summer program in June. She goes all in, too, leaving her apartment and new husband in Nashville to share a house with a fellow female student in Sewanee (an hour and a half away) for the semester and clearing her calendar of concert dates.

“I have a couple of gigs during school, but I really try to keep myself in this kind of academic setting just so I don’t have to keep leaving and coming back,” she explains. “I like to try and stay in that headspace while I’m here. Also, I just like to get away from what I do all year long, anyway. It’s nice to be in a different environment, a really quiet place where you can just have the freedom to try new things.”

Heady coursework and all-nighters aside, she almost makes her summer in academia sound like a vacation. But more than anything else, it’s just another conscious step outside of her natural comfort zone — not unlike the one Shires made back in 2008 when she first moved to Nashville from her native West Texas. She had no designs on becoming any kind of big country star; she just wanted to buckle down and concentrate full-bore on becoming a songwriter, sans the safety net/distraction of constant gigging back and forth across Texas as a fiddle player for hire.

Heady coursework and all-nighters aside, she almost makes her summer in academia sound like a vacation. But more than anything else, it’s just another conscious step outside of her natural comfort zone — not unlike the one Shires made back in 2008 when she first moved to Nashville from her native West Texas. She had no designs on becoming any kind of big country star; she just wanted to buckle down and concentrate full-bore on becoming a songwriter, sans the safety net/distraction of constant gigging back and forth across Texas as a fiddle player for hire.

“Moving to Nashville was like a test to myself to quit being a side person, to try and start over and re-establish myself,” Shires explains. She only knew three people in town when she got there, but stuck it out waiting tables in order to put out her second album (albeit the one she insists on calling her first): 2009’s West Cross Timbers. Five years and two more solo albums down the line, she’s still getting acclimated.

“Some people still ask me when am I going to move to Nashville, because I haven’t learned my directions around town yet,” she admits. “And coming from Lubbock, Texas and Mineral Wells, Texas, it’s hard to think that your home could be a place that has trees and where it rains, you know, like every other day. So it took a while for it to feel like it was home for me. But that’s sort of changed a lot for me now.

“I’m trying not to sound cheesy,” she continues after a pause, “but home for me now is wherever my husband is. We could be living in a tent somewhere and it wouldn’t matter.”

Hallmark sentiments like that one seem to be bit outside of Shires’ comfort zone, too; but she’s woman enough to own up to it — and artist enough to embrace it. Shires has a tattoo (one of many) of a small red heart on her left wrist, inked as a permanent reminder of one of her favorite quotes by Sylvia Plath (from the short story “The Fifteen-Dollar Eagle”): “Wear your heart on your skin in this life.” She wears it openly on her new album, too, most notably with a paean to commitment and true love called “Stay” that rings as forthright and unguarded as the carnal urgency and slow-burn seduction of Carrying Lightning’s “Shake the Walls” and “Sloe Gin.” As a songwriter, Shires has never been one to shy away from full emotional disclosure, so when singing the naked truth calls for showing a little self-professed “sappy” tenderness, she’s up to the task.

But Shires being Shires, she’s also not one to leave good enough alone. Every ray of sunshine she lets into Down Fell the Doves casts a dozen shadows — some real, some imagined, but every one of them more uncomfortable than the last. Put it this way: those doves aren’t falling from the sky for their own good — and Shires really loves birds.

Like the MFA candidate that she is, Shires describes the album analytically as a study in contrasts: no life without death, no good without bad, things falling apart and being rebuilt, etc. And she insists that it’s more “the juxtaposition of sounds and images and musical setting” that interests her, “rather than just ‘the dark.’” But as much as that all may hold up under critical scrutiny, she also concedes that there’s another factor at play behind the album’s not infrequent forays into bleaker corners. Call it what she does: a nagging paranoia that all good things are doomed to end.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” Shires admits. “Maybe it’s just because you remember things that have happened before that were bad, and you can’t help but revisit all those bad things in your head to try and learn more about your fear. It’s just the way I deal with things, I guess. But then sometimes when you talk to somebody else about your problem, you hear it and go, ‘That sounds so stupid when you say it out loud — that’s crazy person talk!’

“So yeah, I really don’t know,” she says, then laughs. “Maybe I need to see somebody?”

***

“I wanna look like a bird, like I was meant to sing

I wanna look like a bird, like I know my place in the world

Like I know my place in the world.”

— Amanda Shires, “Look Like a Bird”

“When I get my wings, hey I’m gonna fly.”

— Billy Joe Shaver “When I Get My Wings”

Going all the way back to her salad days with the Ranch Dance Fiddle Band, the pre-teen, chuck-wagon campfire music sensations of Lubbock, Texas, Amanda “Pearl” Shires has been performing music in public now for more than half her life. She fell in love with and acquired her first fiddle at age 10, after spying it in the window of a Mineral Wells pawn shop while visiting her dad (after her parents divorced when she was a toddler, Shires and her younger sister were raised primarily by their mother in Lubbock). Classical violin lessons and school orchestra she could take or leave, but traditional fiddle tunes and Bob Wills’ Western swing music rocked her world. By 15, she was charming crowds as the youngest-ever member of the legendary Texas Playboys (not to mention the first Playboy to play in pigtails), and by college she was crossing over into alt-countryville with a Levelland band of Panhandle hipsters called the Thrift Store Cowboys. The Playboys doted on her like a granddaughter. The Cowboys treated her like one of the guys. And the whole time, Shires never really once wanted to do anything up there on those West Texas stages of her wonder years but play her fiddle.

“I finally started singing with the Thrift Store Cowboys, after our first record (2001’s Nowhere With You) came out,” she says. “Daniel Fluitt stood a mic in front of me and said, ‘Sing harmony!’ I started out standing six feet away from the mic but slowly got used to it.”

She gradually started writing songs to sing with the band, too, though both her singing and writing still played second fiddle to her fiddle, at least as far as she was concerned. It was her fiddle playing that was starting to land her more and more gigs in the area as a side person, and her fiddle that she wanted to showcase when she decided to make a record of her own, 2005’s Being Brave. “I just wanted to have something that represented what I was doing at the time, that I could sell on the road for a little extra money when I was working for other people,” she says. The record was mostly traditional instrumentals, but she also sang the old Roy Acuff tune “Low and Lonely” for variety’s sake. Then on a lark she added a couple of her early originals and a co-write with the Cowboys’ Fluitt — “just to fill it out, so people would know I could also sing harmony and things like that.”

She gradually started writing songs to sing with the band, too, though both her singing and writing still played second fiddle to her fiddle, at least as far as she was concerned. It was her fiddle playing that was starting to land her more and more gigs in the area as a side person, and her fiddle that she wanted to showcase when she decided to make a record of her own, 2005’s Being Brave. “I just wanted to have something that represented what I was doing at the time, that I could sell on the road for a little extra money when I was working for other people,” she says. The record was mostly traditional instrumentals, but she also sang the old Roy Acuff tune “Low and Lonely” for variety’s sake. Then on a lark she added a couple of her early originals and a co-write with the Cowboys’ Fluitt — “just to fill it out, so people would know I could also sing harmony and things like that.”

Some time after finishing Being Brave (a lovely record, by the way, no matter how much she tries to downplay it now days), Shires landed a handful of shows over a few months playing fiddle for Billy Joe Shaver. They bonded over the old country albums he’d play in his car en route to gigs, sometimes over long distances. Road trips with the legendary honky-tonk hero, Shires affirms with a fond laugh, were both “awesome” and “scary as hell”: “He’s in some kind of big town car, he’s got one of those radars for cops, and he has, you know, no care for real signage on the road or anything, even construction barrels.” He did have a high regard for old swing music, though, and upon remembering that Shires had made a record of fiddle tunes, asked to hear it. Only it wasn’t the fiddle tunes that jumped out at him.

“He listened to the record and said, ‘You know, you really could be a songwriter. There’s no loyalty in side work, and you’ve got something with your writing, so you should work on that.’

“That was a really prophetic kind of moment for me,” Shires marvels, “I was like, ‘What? Are you kidding me?’ But I sat with it a while, and then I was like, ‘Well, maybe he’s right … he’s an old guy, he knows what’s up!’ He’s a crazy dude, but also a caring spirit. So I took his advice. I took it from there and started trying to write and record.”

Shaver’s encouraging words gave Shires her writing wings, but in order to fly she had to take a leap of faith outside of her Texas fiddle player safety nest. Her move to Nashville to “start over” was a big part of her artistic growth, but so too was the fortuitous friendship and professional partnership that she struck up with singer-songwriter Rod Picott. She met the native New Englander and longtime Nashvillian (perhaps best known ’round Texas for his many co-writes with childhood buddy Slaid Cleaves, including “Broke Down”) at a Folk Alliance conference in Austin. As a duo, Picott and Shires toured both nationally and throughout the U.K. and Europe, and they even co-wrote and recorded an album together, 2008’s Sew Your Heart with Wires (voted the fourth best debut album of the year by independent radio DJs reporting to the Freeform American Roots chart.) Picott also co-produced and played on both the album Shires considers her official debut as a solo singer-songwriter, 2009’s West Cross Timbers, and her 2011 breakthrough, Carrying Lightning.

Shaver’s encouraging words gave Shires her writing wings, but in order to fly she had to take a leap of faith outside of her Texas fiddle player safety nest. Her move to Nashville to “start over” was a big part of her artistic growth, but so too was the fortuitous friendship and professional partnership that she struck up with singer-songwriter Rod Picott. She met the native New Englander and longtime Nashvillian (perhaps best known ’round Texas for his many co-writes with childhood buddy Slaid Cleaves, including “Broke Down”) at a Folk Alliance conference in Austin. As a duo, Picott and Shires toured both nationally and throughout the U.K. and Europe, and they even co-wrote and recorded an album together, 2008’s Sew Your Heart with Wires (voted the fourth best debut album of the year by independent radio DJs reporting to the Freeform American Roots chart.) Picott also co-produced and played on both the album Shires considers her official debut as a solo singer-songwriter, 2009’s West Cross Timbers, and her 2011 breakthrough, Carrying Lightning.

“Rod was very influential in that we had a lot of conversations about songwriting, and he was really encouraging and supportive when I started playing ukulele — and anytime you start learning a new instrument can be very tiring for someone else’s ears,” Shires says. “Plus he’s just a really genuine and honest person, and a rare guy in the music business in that he feels empathy and sympathy for people. I was really lucky that I got to spend so much time with him, because I wouldn’t be the person that I am right now if it hadn’t been for him.”

***

“A swarm of sparrows rising

over a cane field,

hearts ascend like that.

Falling is the closest to flying

I believe we’ll ever get,

we’ll ever get.”

— Amanda Shires, “Drop and Lift”

Graced with original material as strong as “Mineral Wells,” Shires’ devastatingly poignant reflection on the aftershock of her parents’ divorce, West

Graced with original material as strong as “Mineral Wells,” Shires’ devastatingly poignant reflection on the aftershock of her parents’ divorce, West

Cross Timbers went a long way towards verifying Shaver’s instincts about her songwriting potential. But Carrying Lightning was the real proof. The album was an end-to-end stunner, steeped in exquisitely crafted and richly detailed lyrical examinations of emotional friction and restless romanticism, all set against a musical backdrop of equally evocative, duskily gothic Americana. It walloped, sighed and ached like Lucinda Williams’ Car Wheels on a Gravel Road sweetened with hallucinogenic honey.

Down Fell the Doves, recorded in Athens, Ga., with producer Andy LeMaster (Bright Eyes, R.E.M.), follows stylistic suit but raises the chill factor. Though lightened with moments of tenderhearted optimism, bliss, humor and playful fantasy (like the aforementioned love song “Stay,” the exuberant “Wasted and Rolling,” the sly “Bulletproof,” and the delightful “A Song for Leonard Cohen”), by and large Doves is a record full of the kind of places and questions sensible types give a wide berth. But there’s just something bewitching about the curious juxtaposition of Shires’ fetchingly folksy, West Texas lilt of a voice and the haunted undertow of her melodies and violin that lures you in, like a siren seducing sailors into rocky waters. In “Deep Dark Below,” she sings about the evils that men do under the spell of madness (“Monsters are men that the devil gets in … to entertain himself awhile”), and “Box Cutters” finds her fantasizing about the myriad ways she could shuffle off her mortal coil, just as casually as shedding a robe before a bath. And in songs like the dangerously pretty “If I” and the aptly titled “Devastate,” she cuts deep into the heart with surgical precision to expose — or is it plant? — the seeds of doubt and fear that can undermine even the healthiest of relationships. By the time the album reaches its final destination amongst the fallen doves, wilted roses and broken silver fountain in “The Garden,” her starkly haunting post-mortem on a dead relationship, you’re ready to go back to “Box Cutters” for pointers.

But other than that, Amanda, how was the honeymoon?

“Whenever I am completely happy, I always fear the worst is inevitable,” she confesses, then muses lightly, “That must be some kind of cherophobia or something.

“But I don’t think I am getting progressively darker,” she continues. “I just think it’s like that thing Townes [Van Zandt] said — you either play zippity doo dah, or the blues. It’s a well, and you don’t get to choose what you draw out of it.”

And in Shires’ defense — or more importantly, in her husband’s defense — all of the songs on Down Fell the Doves were conceived well before the couple’s nuptials in February. They’re still of recent vintage, with most of them written and tracked in 2012, but the well she was drawing from went deep into an emotionally trying two years of her life that predated even the very beginning of the couple’s courtship. While Carrying Lightning was collecting its glowing reviews and Shires was being swept along in its momentum, she was coming fresh out of a break up and — no less or maybe even more crushing in her eyes — mourning the loss of her favorite fiddle of 15 years in a stage accident. And then she broke her finger — specifically, the third finger on her left hand (“A good finger for playing fiddle,” she deadpans). It happened during her first semester at Sewanee in 2011, when she and some friends knocked off from class to go swimming at a local reservoir. Shires swears she was “sober as a judge,” but the rope swing she took an ill-fated turn at didn’t care one way or the other. It tangled around her finger and snapped it like a twig.

“I knew something had happened when I came off that rope and landed in the water,” she recalls. “It was painful, but it wasn’t as painful as when I was trying to swim to shore and could feel the drag of it. And then all this adrenaline comes, and I look up and my finger’s on backwards. It was completely turned around and broken in three places.”

The slow road to recovery with her hand and livelihood locked up in a cast were brutal. “I couldn’t imagine ever playing again, but the specialist I found was pretty confident,” she says. “He went, ‘I’m pretty certain you’ll be able to play again, just do what we say. But that finger’s not going to ever be just like it was.’ Which was very depressing. You have a cast and you can’t practice, and then you have surgery and you can’t practice, and then you have to have a cast again after surgery. So I didn’t play for a long time, and when I could, it took a lot of re-learning. And an emotional struggle just to fight that dark place you go to, where you’re like, ‘I can’t do it, it’s not going to be the same, it’s not going to be worth it.’

“But at the same time,” she hastens to add, “it was also a really humbling experience, because even though that finger will never be what it was, well, hell — I still get to play the fiddle! So what if I’m not 100-percent and so what if I’m not going to ever be the best in the world? I can still play, and it’s the music that makes me happy. It’s not the technical skill of it that’s important — it’s the art of doing it.”

Also helping to fill that glass half-full perspective was the supportive presence of Isbell — and the blooming of their longstanding friendship into something more. They had known each other for years, first crossing paths in Georgia about a decade ago when Shires was on tour with the Thrift Store Cowboys and Isbell was still a Drive-by Trucker.

“We became friends and stayed friends, and occasionally I’d play some shows as a fiddle player for him or play on records if he needed it,” she says. “It took a long while for our friendship to develop into what it is now, though. I always liked him, but I was just fighting my own self, because I’m kind of a person that’s unsure and I would say fearful of relationships. Either you get hurt a few times or you get tired and start guarding yourself. But he was very persistent …”

In a way, her mangled finger helped close the deal.

“This is going to sound like one of those cheesy melodramas, but he came to Sewanee one time, just to visit the school and stuff,” she says. “He found out I broke my finger, and I was like, ‘I have a doctor’s appointment, but I can’t drive because they put a cast the size of, I don’t know, Texas, on my left arm.’ And he said, ‘I’ll come get you and take you to your doctor’s appointment.’ Only I didn’t know they were going to reset my hand that day. They gave me a shot in the hand and then … well, it was not an experience that was pretty at all for anybody to watch, you know? And then you have a girl crying, that’s always great, too. But he still liked me. He liked me at what was one of the worst times for me, and was so supportive. And then out of that, it just became a deeper understanding over lots of conversations.

“That’s when things started looking up,” she says — happily, of course, but also sort of matter of factly. Because “looking up” is just what things usually do, eventually. Shires’ busted-up finger healed — not perfect, but good enough for a determined Texas gal not afraid of a little discomfort for the sake of art to play fiddle again, and she does. Not the cherished one that broke two years ago, but the new one she finally settled on about a year later.

“It’s got a different soul inside of it than my crushed one, but it’s a lovely beast,” she says. “We’re friends now. It took a while but I shouted and it squawked, and now that we’ve spent some time on the road together, it’s even better.”

Kinda like how things panned out between her and Isbell.

In Down Fell the Doves’ “Drop and Lift,” Shires sings of the rise and fall of hearts in chests, each beat signifying the stirring sensation of falling “in and out and out and in and out of love again.” It’s an arresting metaphor for the balance and rhythm of life, distilling all of the agony and ecstasy of the album into three-and-a-half minutes of swirling, exhilarating beauty. And the fact that it’s sequenced two songs before the grim final scene painted in “The Garden” is what ultimately closes the album on an unsung but understood note of hope. From the wreck and ruin of total devastation, there’s really only one place to go.

Well … maybe not for all of those poor gray-eyed and flightless doves. But Shires is a bird of a different feather.

“I got my first tattoo with a fake ID when I was 15 or 16 years old in Hollywood, Calif.,” recalls Shires, who was visiting family at the time. “It was a dragon, and of course I liked it — it was the best ever dragon tattoo you could imagine when you’re 15 or 16, with a big red sun in the background. But then at age 21 I decided that I didn’t really feel that much like a dragon anymore. So I had it reworked into a phoenix.”

***

RELATED

[…] LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, July/Aug […]