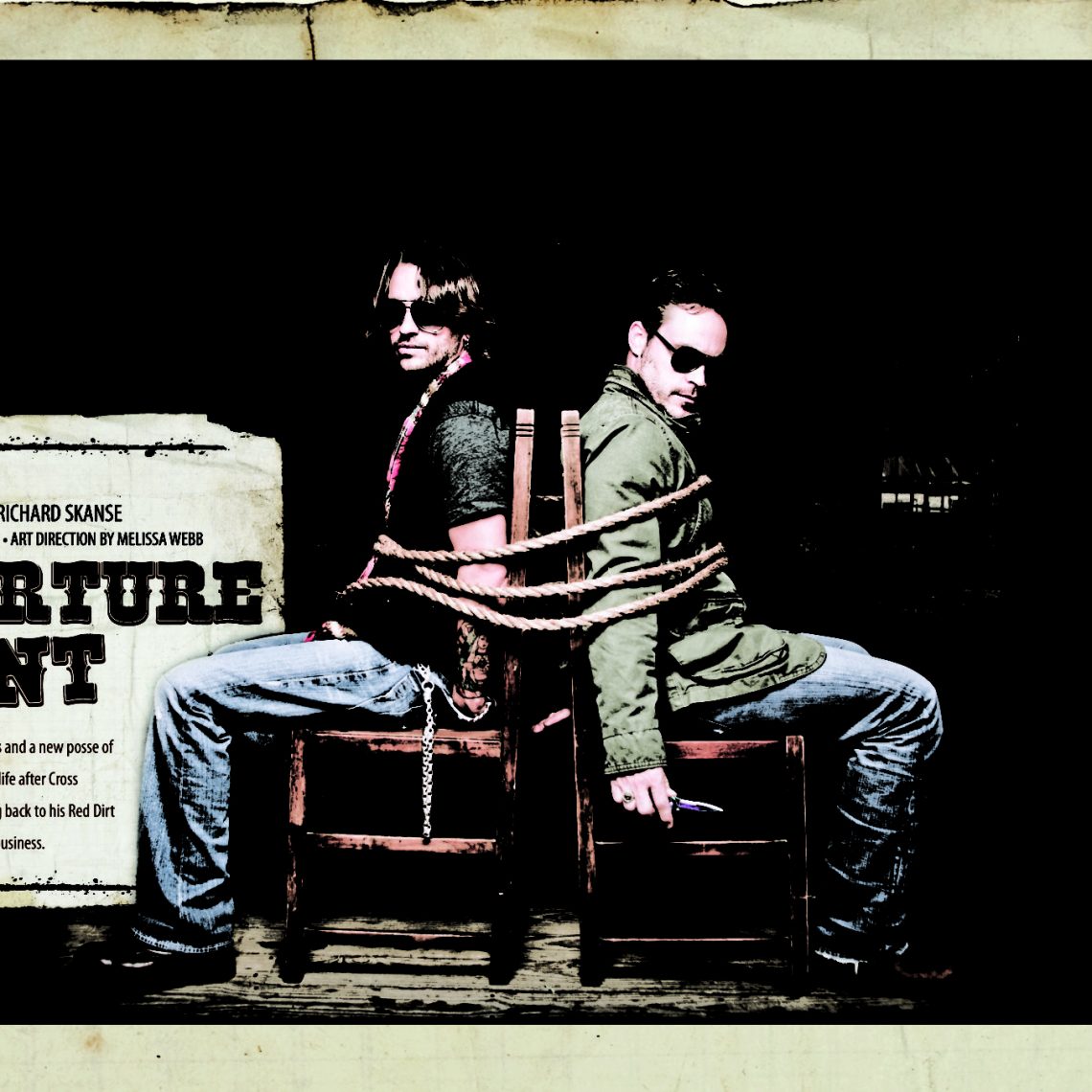

By Richard Skanse

(LSM Jan/Feb 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 1)

On Oct. 24, 2010 — 16 years and 23 days after making its public debut on a trailer bed at Yukon, Oklahoma’s Czech Day — Cross Canadian Ragweed played its swan song in front of a wildly enthusiastic capacity crowd of 1,000 at Joe’s Bar in Chicago. Joe’s — a bastion of Texas, Red Dirt and country music in the heart of the Midwest — was the last show on the books back in May, when the band first announced its decision to take a “break from life on the road.” Fans spent the rest of the summer hoping the respite would only be temporary, but by the time singer/guitarist Cody Canada, bassist Jeremy Plato, rhythm guitarist Grady Cross and drummer Randy Ragsdale walked out on that stage, reality had had enough time to settle in. The last show on the books was going to be Ragweed’s last show, period.

Of course, the diehard faithful will always hold out hope for a reunion somewhere down the line. And who’s to say? According to the band’s official statement back in May, the break was sparked by Ragsdale’s desire to spend more time at home with his family — in particular, his autistic son, J.C.. Ragsdale, the youngest member of the group but also it’s acknowledged founder, reportedly gave the rest of the band his blessing to continue on with another drummer, but they refused, and that was that.

Ragweed’s last hurrah, cont.: (from left) Grady Cross, guest Stoney LaRue, Randy Ragsdale, Cody Canada and Jeremy Plato. (Photo by Jeff Dykhuis)

Perhaps inevitably, rumors later hinted at a somewhat less all-for-one/one-for-all version of events. But the story of Cross Canadian Ragweed, arguably the most successful band to roll out of the Red Dirt/Texas scene in the last decade, won’t be remembered for one bum footnote. It’s the big picture that counts: Four brothers, 16 years, 10 albums and too many miles to count, all boiled down to one explosive finale that lost none of its emotional charge even when chopped into digital bits and beamed across cyberspace via New Braunfels radio station KNBT’s live Internet stream. “We’re gonna cause the second Chicago fire tonight,” Canada cracked at the outset, and for three hours and 15 minutes, Ragweed burned through a 28-song set heavy on guests (Lee Ann Womack, Wade Bowen, Stoney LaRue and Seth James), choice album cuts (“In Oklahoma”), fan favorites (“Constantly,” “Carney Man”), and tried-and-true covers (like the slow-boiling opener, “Mexican Sky,” by fellow Okie Scott Evans.)

A few minutes shy of 1 a.m., after putting “Carney Man” to bed for the very last time, Canada called the band’s management team onstage for a bow. And then he did what had to be done. “Alright, this is it,” he said, trying almost successfully to sound matter-of-fact. Then, after a quick salute to the crowd, a final onstage roll call, and a quick tease — “Stay tuned …” — he fired up the last song of the night: a scorched-earth storm through Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World” that would end an era … and mark the beginning of a new one.

***

Although it didn’t make the final count down any easier, Canada acknowledges now that he knew Ragweed’s days might be numbered even before the band first made public its intent to cut back on road dates.

“I could tell in Randy’s eyes that he had something on his mind, and that he wanted to get home and take care of things with his son,” Canada says. “So when he told us on the phone what was happening, it didn’t surprise me. But still, I balled and squalled on it. And for about two weeks, I was scared shitless.”

Bassist Jeremy Plato sounds like he was caught a little more off guard. “I don’t know that there was any writing on the wall,” he says. “The way it all unraveled was really sudden. And here I was with a newborn on the way, you know? I wasn’t too nervous, though. I was pretty sure I could get another job doing this.”

In fact, it was pretty much a given that he and Canada would end up continuing to work together. Although all four members of Ragweed grew up together in Yukon, Okla., Canada and Plato both now live in New Braunfels (where the band’s headquarters has been based for a number of years). What’s more, they’re now officially family. The mother of Plato’s newborn son is Melissa O’Neal, the younger sister of Canada’s wife (and band manager), Shannon. Jeremy and Melissa will marry this March in Hawaii.

“I’ve had several nights in the back of that bus, listening to Merle Haggard and hugging up next Jeremy, being kind of gay about it, going, ‘Don’t ever leave me, man! I love you! I’ll never leave you!’” Canada says with a laugh. “After that phone call, while we were all kind of in shock, I went over to his house and asked, ‘Well man … we still together?’ He said, ‘Hell yeah we’re still together.’ Like I was an idiot. I was an idiot. There was no question in my mind.”

It’s now early October, two weeks before Cross Canadian Ragweed’s final bow in Chicago, and Canada and Plato are deep in the middle of recording what at one point was meant to be the band’s eleventh album. Back in the summer of 2009, Canada spoke candidly in interviews about Ragweed’s general unhappiness in regards to their well-past-the-honeymoon-stage relationship with the Nashville-based major label, Universal South. Their last studio album, Happiness and All the Other Things, wasn’t even in stores yet, and they were already itching to jump back into the studio to record a tribute album honoring their favorite songwriters from the Oklahoma music scene from which they sprang. That alone would have been a typically defiant middle finger to the powers that be on Music Row — par for Ragweed’s stubborn course. But just to drive their kiss-off point home, they wanted to call the record Contractual Obligations.

Fast forward to the present, and three of the four components of that project — the band, label deal, and the admittedly too-snarky-for-its-own-good title — are all no more. But the heart of the matter still beats strong and true. Now titled This is Indian Land, the record remains comprised entirely of covers written by the Red Dirt State’s finest, ranging from your more internationally known artists like Leon Russell, J.J. Cale and Kevin Welch to comparatively more underground stalwarts like Bob Childers, Tom Skinner and various members of the Medicine Show, the hippie jam band that added a touch of psychedelic rock to the Red Dirt scene in the ’90s. Due out in April, This is Indian Land will be the debut release by Cody Canada & the Departed — and the last.

“We’re going to drop the first part of that after this record, and just be the Departed,” Canada explains. “I’m a band guy, not a solo guy. We’ve got plans for a whole new project, a new rock ’n’ roll thing, so doing this record together is just getting us good and warmed up for the next act.”

That “us” includes not only Canada and Plato, but also another childhood friend, drummer Dave Bowen. Bowen’s late father actually gave Plato his first bass guitar lesson. After high school Bowen moved to New York and hung around the jazz scene for a spell before finding his way back to Oklahoma, where Plato found him working in a music store. “Plato said, ‘Why aren’t you on the road?’” Bowen recalls with a laugh. “I went, ‘What do you mean on the road? Like with the circus?’ It never dawned on me in all my life to be in a touring band.” Next thing he knew, though, Bowen was touring all over drumming with Stoney LaRue, Bleu Edmondson and Dale Watson. (According to Canada, Randy Ragsdale actually recommended Bowen as his replacement in Cross Canadian Ragweed.) Also essential to the Departed lineup are keyboard player Steve Littleton, formerly of the Medicine Show and, most recently, LaRue’s band, and roadhouse rocker/blues guitarist Seth James, with whom Canada played a number of “Two Man Electric Jam” dates after Ragweed’s schedule opened up last summer.

James, whose 2009 That Kind of Man album was released on Ragweed’s Underground Sound label the same week as Happiness and All the Other Things, is putting his own solo career on hold to ride with Canada’s new gang. But the native Texan will be the crucial “X” factor when it comes time for the Departed to step out and distinguish themselves from Cross Canadian Ragweed. Moving forward after the transitional This is Indian Land project, Canada and James will be sharing both frontman and lead guitar duties in the band.

“The plan is to tour this record for a few months, then when we get enough material, just jump right into the next record,” Canada says. “So at first we’ll be doing the songs on this record, plus some Seth songs and a couple of Ragweed songs, but moving on to the next one, Seth’s going to be singing and I’m going to be singing, and it’s all going to be new music — just a whole new thing.

“Shit,” he continues. “Collectively, we’ve got 30 years of playing between us. I’m not saying we’ve made a good mark or a bad mark, but we’ve been doing this for a really long time. So now, let’s do something different. Let’s start from scratch, and build it all over again. Seth and I sat down to write one day, and as we got to talking about this new venture, we both got really, really excited about it. We were kind of cocky about it! Like, ‘This is going to be badass!’”

James, who played his last “Seth James Band” gig — at least for a while — at Gruene Hall in November, is very much on the same page.

“I’ve always had stacks and stacks of songs — more rock ’n’ roll oriented stuff — that I’ve never felt I could really use in the right way until now,” he enthuses. “You just want to be able to play music you love with people you love, and that’s where we’re all at, so it’s a good thing. It’s going to be fun. But we want to come out of the gate swinging with something that we’re really proud of, so we’re going to take however much time it takes to get it done right … and then, hopefully, it will spread like wild fire.”

***

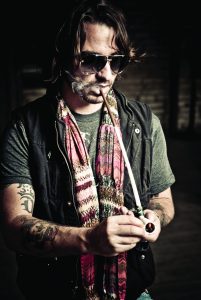

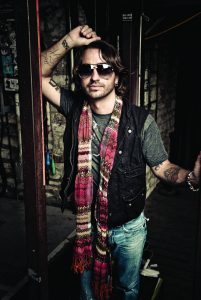

On the surface, Canada and James appear to make a strange pairing. In spite of Cross Canadian Ragweed’s end run on a Nashville-based country label, Canada was always first and foremost a rock ’n’ roller. On a scene choked with young wannabe Waylons all aspiring to be later-day country outlaws, Canada and the rest of the band he led for a decade and a half were doing that and rocking Ted Nugent covers and paying respects to Dimebag Darrell, the renowned Dallas heavy-metal guitarist who was murdered onstage at a 2004 Damageplan concert in Ohio. And though by no means uncomfortable playing acoustic singer-songwriter fare from a stool, Canada seems most in his element when swaggering across a stage and slashing out riffs on an electric guitar. He’s built like a rock star, too, his liberally inked frame wiry and slim enough to give any skinny-jeans-wearing hipster — male or female — body image anxiety. Not that Canada himself would ever mix with the ironic posturing crowd, though; although there’s an edge about him suggesting a keen intelligence beyond just street smarts, his offstage vibe is very much classic, slacker pothead. Apart from the whole charismatic rock star thing, he seems cut from the same muscle-car cruising, cocky-stoner cloth as Matthew McConaughey’s character in Dazed and Confused. (“Say man, you got a joint? It’d be a lot cooler if you did!”)

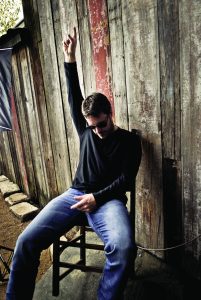

By contrast, James is the Southern gentleman/Marlboro Man incarnate. The grandson of a Texas Ranger (and not the baseball variety), he was raised on his stepfather Tom Moorehouse’s family ranch in King County, Texas. “I’ve spent my whole life on the back of a horse,” he says. “It’s a very unique way of life out there. We lived isolated from everything and did things the way they did 100 years ago — sleeping on the ground, eating out of a chuck wagon, breaking our own horses. When I went off to college, I went from growing up 30 miles outside of a town that had one stop sign and 200 people in it to College Station, which was such a big culture shock to me, it might as well have been Houston.”

James had trouble mixing with the other ranch-hand types at A&M. “I know this sounds snotty,” he says sheepishly, “but guys from West Texas don’t think there’s any real cowboys in East Texas.” So he spent his college years focusing on his studies and music — the later a passion he’d picked up from his birth father. “Pretty much that whole side of my family is musicians,” he says. “My granddad played in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, and my dad put himself through college by playing. And his great-granddad was a pretty hot banjo picker.” The first song his dad taught him to play was “Sultans of Swing” by Dire Straits. From there, he went blues crazy: Jimmy Reed, Freddie King, B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Elmore James, Johnny Winter, Stevie Ray Vaughan, etc. The songwriting styles of Delbert McClinton and Leon Russell also made an indelible impression on him, as heard on the trio of releases he put out in the last decade: 2001’s Bad Luck and Trouble, 2004’s Live at Gruene Hall and 2009’s That Kind of Man. His catalog would likely be a title or two deeper if not for the four years he lost working on a record for Sony Nashville that — “long story short” — didn’t pan out. “Going through that was a good experience, though, because I met a lot of good friends, learned a lot about the business and grew a lot as a songwriter. But it did take up a large chunk of my record-making time.”

He still found time to tour, though, building up his own audience as well as opening many a show for Cross Canadian Ragweed. Canada recalls James first joining the band onstage at the urging of the late Blaine Martin at Blaine’s Pub in San Angelo. James says he can’t remember that meeting (“because Blaine had a talent of making you not able to remember things!”), but he notes that he and Canada actually first crossed paths much earlier than that.

“I think the first time we met we were little, little kids, in Seymour, Texas,” he says. “My grandparents lived there, and he had some family there too. We met at the big Seymour Easter Egg Hunt at the park. I actually knew his sister and her husband for a long time, just from being from that area, and a bunch of his dad’s cousins were all cowboys, just like my granddad out there.

“As far as really getting to know each other, that didn’t happen until years later, when we started bumping into each other out on the highway,” he continues. “But our paths are actually very similar. I know we look so different, like he’s from another world than me, but he’s really not. Like, his dad and my dad are the same damn person. All this North Texas cowboy culture, all the weird things that I say that nobody knows, he knows all that stuff. And we’re really so much alike in the way we grew up, down to the slightest detail — right down to when our parents divorced. I think he’s a year older than me, and our birthdays are one day apart. There’s just all kinds of weird stuff like that that comes up. It’s kind of like we grew up in the same town.”

Whatever North Texas roots they might have shared, though, Canada’s musical coming of age was uniquely Oklahoman. Although the guys in Cross Canadian Ragweed all met and first played together in Yukon (the same small town just east of Oklahoma City that gave the world Garth Brooks), their real journey really began further north in the college town of Stillwater. That’s where Canada first started seriously honing his performance chops at the infamous Wormy Dog (immortalized on the band’s first live album), and, perhaps more significantly, found his home away from home at “the Farm,” the legendary Mecca for Red Dirt songwriters right outside of town.

“I basically lived there,” Canada recalls fondly. “I’d sleep on the Farm couch, which was a dirty, smelly old couch, but it wasn’t a gross place at all. It was just a hippie compound, you know? And I was just a teenager, but I remember thinking, ‘Man, this is something!’ That’s how I always explain it: You really felt like you were experiencing something, but you just didn’t know what it was yet! But that was when I first met not only (Jason) Boland and Stoney, but Mike McClure and Tom Skinner and Bob Childers and the Medicine Show and the Red Dirt Rangers — all those guys. I remember when I was 17, Tom kind of took me under his wing. I was sitting in a lawn chair one night, watching him play, and he called me up to sing a song, and I was the most nervous I’ve ever been in my entire life. And then he put this record together and asked me to be a part of it. I’m 34 now, and I’m still not over that. But that’s how those people are; they’re just good folks, and they take care of each other. Tom had a heart attack or a stroke back then, and we did a big benefit concert for him. And Childers was living in the trailer on the Farm, and it burned down, and everybody gathered around and raised money and took care of him. Because that’s how that community works.

“Childers had a songbook that was about 10-inches thick, and it was the only thing in that trailer that didn’t burn,” Canada marvels. “It had songs he wrote with Garth, a song he wrote with (Jerry) Garcia, stuff he wrote with members of The Band … Because Bob hitchhiked all over the place. He was born somewhere in Texas, I believe [West Virginia, actually], and he made it to Oklahoma, lived there for awhile, and then hitchhiked to San Francisco and lived there from ’67 to ’70. And then he hitchhiked back this way and landed in Stillwater and went, ‘This is where I need to be.’”

Fittingly, the Childers song Canada recorded for This Is Indian Land is one he co-wrote with members of the Medicine Show, called “Make Yourself Home.”

“This record is full of songs that I know, that I’ve known forever,” he says. “But with the exception of maybe one or two of them, nobody else outside of Oklahoma has really heard them. I’m not trying to be cheesy and build it up, but this album is the one that I’ve been wanting to do for years. It’s about giving back to those guys who taught us how to be good people and good musicians and support each other … just the Oklahoma way, you know? And I hate to admit it, but I got away from that for a while. I got stressed about writing songs for the next album of ours. But once Ragweed started slowly disappearing, when we knew that was coming, that’s when I dove right back into it. And now I feel like we’ve got it by the balls again. Especially with this group of jammers.”

***

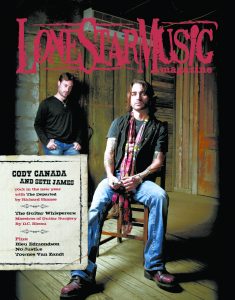

The Departed, from left: Steve Littleton, Seth James, Cody Canada, Jeremy Plato, and Dave Bowen (Photo by Valerie Fremin)

At the time of this writing, This Is Indian Land is still a work in progress. A firm release date hasn’t even been set yet, though Canada says “sometime in April” (after Plato’s March wedding) with a confidence that seems bankable. It will more than likely be released on Ragweed’s old homegrown Underground Sound label, unless a better offer comes along between now and then. Meanwhile, Cody Canada & the Departed are already booked for a handful of shows, including their official debut on Dec. 29 at Gruene Hall and a return to Joe’s Bar in Chicago on Jan. 14. They will also be one of the very first acts to break in the stage at the new Austin City Limits Live venue in downtown Austin (Feb. 11).

Right now, though, the band is still in the middle of another long day at Yellow Dog Studios in South Austin, laying down tracks. Engineer Adam Odor is at the controls (the band is self-producing the album), and Canada, James, Plato, Bowen and Littleton are behind the glass, grooving in the funky, psychedelic swirl of “Face on Mars,” by the singularly eclectic Okie singer-songwriter/fiddle player Randy Crouch. Last night, the song’s tricky rhythm apparently kicked their ass, but today they’ve nailed it down — thanks in part to Odor’s excitable revelation that what the track really needed was a Motown drum beat. The end result is every bit as out there as the Frank Zappa-esque Crouch original that Canada, Plato and Bowen were listening to earlier this morning on the bus. Well, almost.

“I talked to Randy Crouch for about 30 minutes today on the phone, and he said, ‘When you guys get done with this tune, we’ll go to Mars and we won’t even need a spacesuit!’” Canada relates with a laugh. “I’d been trying to get ahold of that guy for three months. I thought I was going to have to send smoke signals. I would really like to have him play fiddle on the record, just because he’s so fucking awesome. I mean, the guy plays guitar and fiddle like Jimi Hendrix. He lives out in the hills, way back in the sticks, and looks like Charles Manson, but he’s the sweetest guy you could ever meet.”

In addition to the Crouch tune, the band will track two more songs before calling it a day: “If You’re Ever in Oklahoma” by J.J. Cale, and “Kickin’ Back in Amsterdam,” one of the album’s two Kevin Welch covers (the other being “True Love Never Dies”). Other songs expected to make the record include the aforementioned Childers/Medicine Show co-write “Make Yourself Home,” Leon Russell’s “Home Sweet Oklahoma,” “The Ballad of Rosalie” by Randy Pease, “A Little Rain Will Do” by Greg Jacobs, “Staring Down the Sun” by the Red Dirt Rangers, “Hold On, Christian” by Scott Evans of the Medicine Show, and three Tom Skinner songs: “Water Your Own Yard,” “Skyline Radio” and the Mike Shannon co-write “Long Way to Nowhere,” which Plato gets to sing.

There’s also another old tune, “Any Other Way,” which stands out as the only song on the record actually written by one of the members of the Departed. “Cody knew it was a Medicine Show song, but he couldn’t quite remember it,” says Littleton, the oldest member by about eight years. “It was a funny thing, because we were in rehearsal and he was like, ‘There was a song that went, “Stick around till the day I die …” Hey, Plato, what was that song?’ And I said, ‘That’s “Any Other Way.” And Cody goes, ‘Do you know that song?’ I laughed and said, ‘Hell yeah, I wrote it!’ So, I don’t think me being a part of this project had anything to do with them putting that song on the record — that was just a coincidence. But I can’t tell you blown away I am by the fact that they decided to do this project in the first place, and also that they asked me to be a part of it.”

The songs on this first record may all be covers, but both on album and onstage, having Littleton’s keyboards in the mix should go a long way toward helping the Departed establish a sound of its own. So, too, will the almost blood-brother-like syncopation of the Plato and Bowen rhythm section, with its roots extending way back to their pre-teens (“When we were kids, probably 12 or 13, David and I were going the save the world with our jazz-metal confusion,” Plato quips. “We were waiting for Steve Vai to call,” adds Bowen.) And last but not least, there’s the intriguing promise of the band’s two very dynamic but stylistically different lead guitarists (and co-frontmen).

“I think we compliment each other really well,” James enthuses. “Our styles are different enough that we don’t step on each other’s toes at all. Cody plays guitar like Neil Young in Crazy Horse; he just has this real rock ’n’ roll way of playing guitar — a real, straight-up, old-school classic rock approach. But I never listened to Ted Nugent or Grand Funk to get riffs; I was listening to Freddie King or even people like David Grissom. We just come from two totally differently places guitar-wise, and because of that, I have no doubt that anybody listening, whether they’re guitar people or not, will be able to hear the record and go, ‘That’s Seth, that’s Cody.’ It’s always very apparent who’s playing, and that’s a really awesome — and hard — thing to come by.”

Naturally, Canada seconds that enthusiasm. But the thing he sounds most excited about exploring — after This Is Indian Land is polished off and released into the wild — is the anything-can-happen rush of discovering what direction the Departed’s first batch of original songs will take them in.

“So far, we’ve only finished one song,” he laughs. “Seth and I have got several in the works, but that one we’ve finished, we’re really proud of. It’s called ‘Black Horse Mary.’ It’s a bad girl riding into town — instead of a bad guy. We just practiced it the other day. All three of us sing it — me, Seth and Jeremy — like a call and repeat kind of thing, and it came out exactly how we all envisioned it.

“It’s our first real song,” he says proudly, “and we set the bar pretty high for ourselves.”

No Comment