By Brian T. Atkinson

(LSM Jan/Feb 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 1)

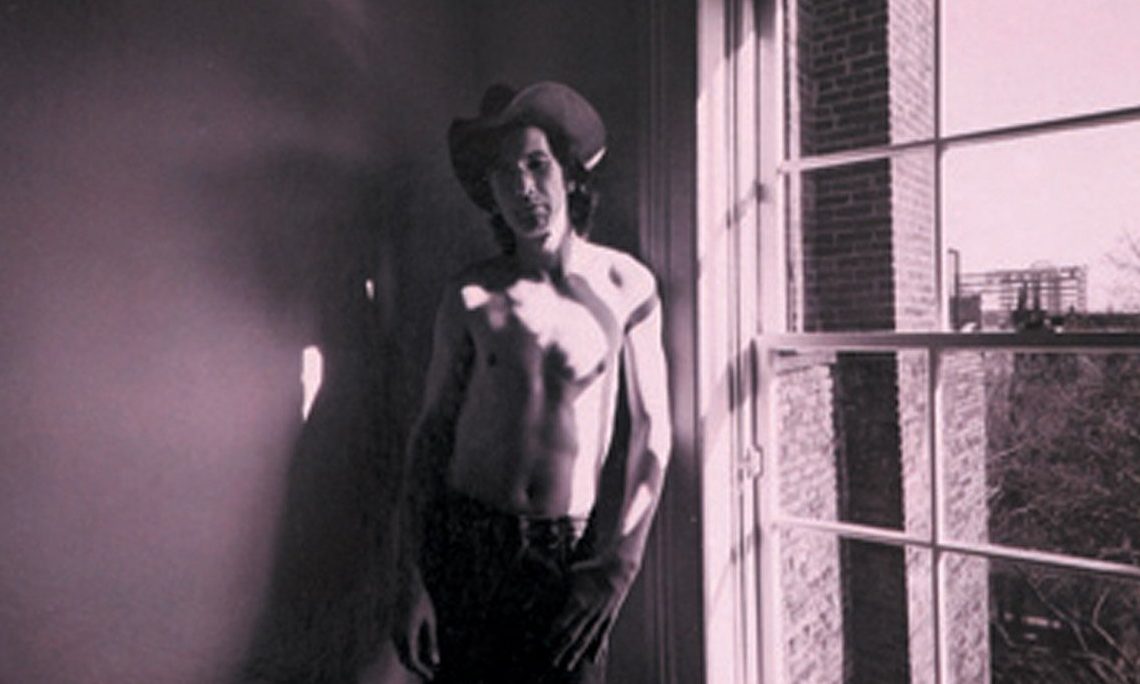

As a young man, Townes Van Zandt wrote with the blazing intensity of a man counting numbered days. He might’ve been.

After all, the Fort Worth native, a cult figure at best outside Tennessee and Texas during his lifetime, made sure his time would be short. “I don’t envision a very long life for myself,” a youthful Van Zandt says early in Margaret Brown’s 2005 documentary, Be Here To Love Me. “Like, I think my life will run out before my work does, you know? I’ve designed it that way.” Van Zandt lived fast and wrote faster, even as his blueprint devolved into alcoholism and drug addiction’s slow suicide.

Along the way, he became the modern era’s most elegant lyricist. Trace his desire slowly: “Well, the diamond fades quickly when matched to the face of Maria/All the harps they sound empty when she lifts her lips to the sky,” he sings on “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria,” one of several highlights from his debut, For the Sake of the Song (1968). “The brown of her skin makes her hair seem a soft golden rainfall/That spills from the mountain to the bottomless depths of her eyes.” Every word frames the woman’s beauty with vibrant imagery, a trademark that ribbons throughout his catalog.

Along the way, he became the modern era’s most elegant lyricist. Trace his desire slowly: “Well, the diamond fades quickly when matched to the face of Maria/All the harps they sound empty when she lifts her lips to the sky,” he sings on “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria,” one of several highlights from his debut, For the Sake of the Song (1968). “The brown of her skin makes her hair seem a soft golden rainfall/That spills from the mountain to the bottomless depths of her eyes.” Every word frames the woman’s beauty with vibrant imagery, a trademark that ribbons throughout his catalog.

Remarkably, Van Zandt composed the majority of his 57 indisputable classics before turning 30 years old. For the Sake of the Song doubles down on “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria” with four additional keepers: “I’ll Be Here in the Morning,” “Tecumseh Valley,” “Waitin’ Around to Die” and “For the Sake of the Song.” Each outlines a depth and despair that his 24-year-old voice would require years to grow into. Meanwhile, Van Zandt feminized his lifelong creative mission statement atop the title track’s simple three-chord melody: “Maybe she just has to sing for the sake of the song/And who do I think I am to decide that she’s wrong?”

Van Zandt claimed his songs literally fell out of the sky. Words rushed through his body. Burned his hands. Our Mother the Mountain (1969) shows it (“Be Here to Love Me,” “Second Lover’s Song”). Van Zandt’s richly crafted sophomore album needs that buoyant energy, for here again, as on For the Sake of the Song, celebrated producer Cowboy Jack Clement drapes Townes’ pristine picking and poetry with blankets of flutes and strings. Nonetheless, “Kathleen,” “My Proud Mountains,” “Snake Mountain Blues” and the title track emerge from underneath the heavy hand as lasting contributions. Ultimately, the album sold as poorly as his first.

Van Zandt claimed his songs literally fell out of the sky. Words rushed through his body. Burned his hands. Our Mother the Mountain (1969) shows it (“Be Here to Love Me,” “Second Lover’s Song”). Van Zandt’s richly crafted sophomore album needs that buoyant energy, for here again, as on For the Sake of the Song, celebrated producer Cowboy Jack Clement drapes Townes’ pristine picking and poetry with blankets of flutes and strings. Nonetheless, “Kathleen,” “My Proud Mountains,” “Snake Mountain Blues” and the title track emerge from underneath the heavy hand as lasting contributions. Ultimately, the album sold as poorly as his first.

However, word spread. Legendary singer Joe Ely began redesigning the Texas music landscape when he discovered Our Mother the Mountain. The Lubbock native excitedly introduced the album, a hitchhiking Van Zandt’s payment for a lift back toward Houston, to his Flatlanders bandmates Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock, who embraced the duality in songs like “St. John the Gambler” and the reworked “Tecumseh Valley.” “[Townes’ songs] sound like simple little love songs,” Hancock says, “and then all of a sudden — zap! — he hits you with a line that makes you look death straight in the face.”

Van Zandt’s next move forward took two steps back. As his reputation grew underground, the songwriter showcased his wares by reissuing more tracks from his first album on Townes Van Zandt (1970). Jim Malloy’s more sympathetic production results in Van Zandt’s most cohesive early studio effort, particularly revealing “For the Sake of the Song” and “I’ll Be Here in the Morning” as purely as intended. New tunes both dark (“Lungs,” “None But the Rain”) and light (“Colorado Girl,” “Columbine”) fortify the increased intensity captured on “Waitin’ Around to Die” and “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria.” The seamless “Don’t Take It Too Bad” unravels as a perfect circle.

Van Zandt’s next move forward took two steps back. As his reputation grew underground, the songwriter showcased his wares by reissuing more tracks from his first album on Townes Van Zandt (1970). Jim Malloy’s more sympathetic production results in Van Zandt’s most cohesive early studio effort, particularly revealing “For the Sake of the Song” and “I’ll Be Here in the Morning” as purely as intended. New tunes both dark (“Lungs,” “None But the Rain”) and light (“Colorado Girl,” “Columbine”) fortify the increased intensity captured on “Waitin’ Around to Die” and “(Quicksilver Daydreams of) Maria.” The seamless “Don’t Take It Too Bad” unravels as a perfect circle.

Van Zandt’s following album simply unravels. Delta Momma Blues (1971) aims for bristling street savvy (the pulsating urban blues “Brand New Companion,” “Where I Lead Me”), but ends up entirely unfocused. Most clearly, Van Zandt’s gentle measures of love (“Come Tomorrow”) and loss (“Tower Song”) feel disjointed against his apocalyptical journey into the abyss at close (“Nothin’”). The opening “F.F.V.” could’ve been left on the floor at New York City’s Century Sound. At least producer Ronald Frangipane (Janis Ian, John Lennon) nails Van Zandt’s seething coming-of-age tale “Rake.” Few songwriters license integrity enough to purge as nakedly.

Van Zandt’s following album simply unravels. Delta Momma Blues (1971) aims for bristling street savvy (the pulsating urban blues “Brand New Companion,” “Where I Lead Me”), but ends up entirely unfocused. Most clearly, Van Zandt’s gentle measures of love (“Come Tomorrow”) and loss (“Tower Song”) feel disjointed against his apocalyptical journey into the abyss at close (“Nothin’”). The opening “F.F.V.” could’ve been left on the floor at New York City’s Century Sound. At least producer Ronald Frangipane (Janis Ian, John Lennon) nails Van Zandt’s seething coming-of-age tale “Rake.” Few songwriters license integrity enough to purge as nakedly.

Wind truly caught Van Zandt’s artistic stride the following year. A writer at the very top of his game, he offered his most indelible landscapes on High, Low and In Between (1972). Many passages prove as exhilarating (“Greensboro Woman,” “High, Low and In Between”) as they are confounding (“You Are Not Needed Now,” “Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold”). Each offers lessons in songwriting, but try topping the Technicolor opening of “Highway Kind”: “Pour the sun upon the ground/Stand to throw a shadow/Watch it grow into a night/And fill the spinnin’ sky.” The album, produced by Van Zandt’s manager Kevin Eggers in Los Angeles, is almost all highs. None soars more effortlessly than “To Live’s to Fly,” Van Zandt’s closest parallel to the Kerouacian blueprint.

Wind truly caught Van Zandt’s artistic stride the following year. A writer at the very top of his game, he offered his most indelible landscapes on High, Low and In Between (1972). Many passages prove as exhilarating (“Greensboro Woman,” “High, Low and In Between”) as they are confounding (“You Are Not Needed Now,” “Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold”). Each offers lessons in songwriting, but try topping the Technicolor opening of “Highway Kind”: “Pour the sun upon the ground/Stand to throw a shadow/Watch it grow into a night/And fill the spinnin’ sky.” The album, produced by Van Zandt’s manager Kevin Eggers in Los Angeles, is almost all highs. None soars more effortlessly than “To Live’s to Fly,” Van Zandt’s closest parallel to the Kerouacian blueprint.

At the same time, Van Zandt’s substance abuse was reaching new lows. By titling his next album The Late, Great Townes Van Zandt (1972), the singer directly taunted a recent heroin overdose. An oak-strong work, The Late, Great builds on Van Zandt’s classic pillars: “If I Needed You” and “Pancho and Lefty.” The songs, while buried unceremoniously near this album’s end, would eventually land Van Zandt atop the country chart for the first and last times thanks to duets by Emmylou Harris and Don Williams (1981’s “If I Needed You”) and Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard (1983’s “Pancho and Lefty”). For good enough reason, fans celebrate those masterfully crafted hits as highest watermarks, but another dark horse truly beats as The Late, Great’s heart.

At the same time, Van Zandt’s substance abuse was reaching new lows. By titling his next album The Late, Great Townes Van Zandt (1972), the singer directly taunted a recent heroin overdose. An oak-strong work, The Late, Great builds on Van Zandt’s classic pillars: “If I Needed You” and “Pancho and Lefty.” The songs, while buried unceremoniously near this album’s end, would eventually land Van Zandt atop the country chart for the first and last times thanks to duets by Emmylou Harris and Don Williams (1981’s “If I Needed You”) and Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard (1983’s “Pancho and Lefty”). For good enough reason, fans celebrate those masterfully crafted hits as highest watermarks, but another dark horse truly beats as The Late, Great’s heart.

Van Zandt wrote the staggering “Snow Don’t Fall” about his 19-year-old girlfriend Leslie Jo Richards, who was murdered while hitchhiking on an errand for him during the Southern California recording session for High, Low and In Between. “My love lies ’neath frozen skies,” he mourns, “and waits in sweet repose for me.” Van Zandt rarely performed the song in concert, but devotees John Gorka and Nanci Griffith recorded an exquisite version years later. The song remains his greatest lesson in lyrical economy. “‘Snow Don’t Fall’ is, what, two verses and a bridge and then repeating the first verse?” Gorka marvels. “It’s such a perfect song in so few lines.”

By this point, Van Zandt’s prolific burst — six quality albums in five years — had made him a living legend among Texas songwriters. Guy Clark, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Joe Shaver and Jerry Jeff Walker led those championing his singular approach. “The inspiration was not to be like Townes,” Clark says, “but to be able to find that place within yourself to write.” Shaver cuts straighter to the quick: “As far as I was concerned, he was the best songwriter that ever lived, and that’s it.” Van Zandt’s next release, his masterpiece, forever proves the point.

Disciples have labeled the songwriter a poet and prophet for four decades now, and their most compelling argument remains Live at the Old Quarter (1977). Taped over a seven-night stand at Rex Bell and Dale Soffar’s Magnolia City club in July 1973, Live at the Old Quarter showcases Van Zandt’s raw narratives, solo and acoustic as intended, before a rare full house and executed in top form. Most agree it’s Van Zandt’s finest moment. “Live at the Old Quarter blew my mind,” the Gourds’ Kevin Russell says. “It’s great, and I think it’s all the Townes you really need.”

Disciples have labeled the songwriter a poet and prophet for four decades now, and their most compelling argument remains Live at the Old Quarter (1977). Taped over a seven-night stand at Rex Bell and Dale Soffar’s Magnolia City club in July 1973, Live at the Old Quarter showcases Van Zandt’s raw narratives, solo and acoustic as intended, before a rare full house and executed in top form. Most agree it’s Van Zandt’s finest moment. “Live at the Old Quarter blew my mind,” the Gourds’ Kevin Russell says. “It’s great, and I think it’s all the Townes you really need.”

All stars align. At 29 years old, Van Zandt performs poignantly (“Pancho and Lefty,” “If I Needed You,”), powerfully (“White Freightliner Blues,” “Tecumseh Valley”) and with blinding force (“Lungs,” “Mr. Mudd & Mr. Gold”). Covers deftly augment his dry wit and easy delivery (“Chauffeur’s Blues,” “Cocaine Blues”). Especially weighed against the mediocre concert albums that litter his posthumous catalog — In Pain, (1999), Absolutely Nothing (2002) and Acoustic Blue (2003) among them — this flawless 27-song set easily stands as his definitive work. “I used to go see him at the Old Quarter when I was a kid,” Jesse Dayton says. “It’d be like seeing Bob Dylan and Hank Williams all rolled into one — if he wasn’t drunk, of course.”

Van Zandt’s errant behavior certainly plagued his success, but the songs themselves might’ve been the strongest repellent. He well understood. “The kind of songs I play — poem songs, story songs — are not what you’d call a particularly accepted mode of art these days,” Van Zandt once said. “Most of those Nashville folks won’t do things in a minor key. Nashville’s just not geared for minor keys.” “Townes was poison to the big labels in Nashville,” songwriter David Olney says. “If ‘Pancho and Lefty’ became where the bar was set in Nashville, a lot of people would’ve been out of work pretty quick.”

Six years after The Late, Great, Flyin’ Shoes (1978) again measured up. Van Zandt’s best studio album effortlessly energizes tales of love (“No Place To Fall”), lust (“Loretta”), desire (“Dollar Bill Blues”) and devotion (“Pueblo Waltz”). Gary Scruggs’ lost and lonesome harp transforms “Flyin’ Shoes” into Van Zandt’s finest daydream yet. Recorded at Chips Moman’s Nashville studio, Flyin’ Shoes features a broad scope of support players — Spooner Oldham (piano), Jimmy Day (steel guitar) and Randy Scruggs (mandolin) among them — that lend unwavering richness to songs like “Snake Song,” “Brother Flower” and a cover of Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love.” No studio effort captures Van Zandt’s essence better.

Six years after The Late, Great, Flyin’ Shoes (1978) again measured up. Van Zandt’s best studio album effortlessly energizes tales of love (“No Place To Fall”), lust (“Loretta”), desire (“Dollar Bill Blues”) and devotion (“Pueblo Waltz”). Gary Scruggs’ lost and lonesome harp transforms “Flyin’ Shoes” into Van Zandt’s finest daydream yet. Recorded at Chips Moman’s Nashville studio, Flyin’ Shoes features a broad scope of support players — Spooner Oldham (piano), Jimmy Day (steel guitar) and Randy Scruggs (mandolin) among them — that lend unwavering richness to songs like “Snake Song,” “Brother Flower” and a cover of Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love.” No studio effort captures Van Zandt’s essence better.

(Side note: Smart consumers will find all seven above studio albums on Charly Records’ excellent four-disc Townes Van Zandt: Texas Troubadour (2001). The only downside is the eight curious choices issued at close from Live at the Old Quarter.)

Nine more years passed before Van Zandt recorded again. His output had diminished significantly in quantity, but quality remained mostly high. At My Window (1987), boasting top session men Mickey Raphael (harmonica), Roy Huskey Jr. (bass) and Kenny Malone (drums), is his most successful collaboration with Jack Clement. Most notably, the producer’s gentler touch allows the album’s bookend highlights to glow like sunset snapshots (“Snowin’ on Raton,” “The Catfish Song”). Van Zandt’s weary vocals prove triumphant and troublesome: Age rings positively haunt the title track and finally perfect “For the Sake of the Song,” but their depth spotlights hollowness echoing throughout the lightweight “Little Sundance No. 2” and “Gone, Gone Blues.”

Nine more years passed before Van Zandt recorded again. His output had diminished significantly in quantity, but quality remained mostly high. At My Window (1987), boasting top session men Mickey Raphael (harmonica), Roy Huskey Jr. (bass) and Kenny Malone (drums), is his most successful collaboration with Jack Clement. Most notably, the producer’s gentler touch allows the album’s bookend highlights to glow like sunset snapshots (“Snowin’ on Raton,” “The Catfish Song”). Van Zandt’s weary vocals prove triumphant and troublesome: Age rings positively haunt the title track and finally perfect “For the Sake of the Song,” but their depth spotlights hollowness echoing throughout the lightweight “Little Sundance No. 2” and “Gone, Gone Blues.”

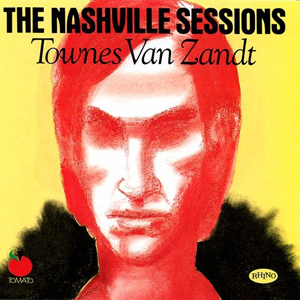

At this point pushing his mid-40s, Van Zandt had already surpassed his expected expiration date by a decade or two. He had only one new studio album left in him, and it would take seven more years — including his only extended stretch of adulthood sobriety and one final dive toward the bottom of the bottle — to get there. The meantime granted dubious asylum to his long abandoned album, Seven Come Eleven (recorded in the early 1970s). By its release, the renamed The Nashville Sessions (1993) was old news. It features plenty of keepers — “At My Window,” “Rex’s Blues,” “Loretta,” “Buckskin Stallion” — but definitive versions had already been cut. Mostly a wash for aficionados, The Nashville Sessions primarily offers two revelations: “White Freightliners Blues” and “Two Girls.” Bluegrass bands have closed a thousand festivals with the former, and the latter offers some of Van Zandt’s most surrealistic lyrics. “The swimming hole was full of rum/And I tried to find out why,” he sings. “All I learned was this, my friend/You gotta learn to swim before you fly.” “I think that verse is just far out,” Clark says. “I quote it all the time.”

At this point pushing his mid-40s, Van Zandt had already surpassed his expected expiration date by a decade or two. He had only one new studio album left in him, and it would take seven more years — including his only extended stretch of adulthood sobriety and one final dive toward the bottom of the bottle — to get there. The meantime granted dubious asylum to his long abandoned album, Seven Come Eleven (recorded in the early 1970s). By its release, the renamed The Nashville Sessions (1993) was old news. It features plenty of keepers — “At My Window,” “Rex’s Blues,” “Loretta,” “Buckskin Stallion” — but definitive versions had already been cut. Mostly a wash for aficionados, The Nashville Sessions primarily offers two revelations: “White Freightliners Blues” and “Two Girls.” Bluegrass bands have closed a thousand festivals with the former, and the latter offers some of Van Zandt’s most surrealistic lyrics. “The swimming hole was full of rum/And I tried to find out why,” he sings. “All I learned was this, my friend/You gotta learn to swim before you fly.” “I think that verse is just far out,” Clark says. “I quote it all the time.”

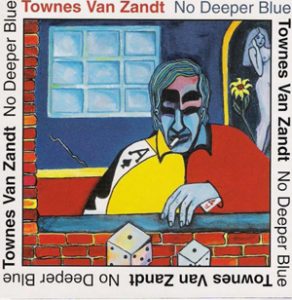

Van Zandt’s recording career concluded with a fizzle. By No Deeper Blue (1994), he finally had earned a weathered and whipped voice for blues, but his most electric effort ironically lacked punch and substance. The album opens strong with two harrowing travelogues into darkness (“A Song For,” “The Hole”) and perhaps the most sympathetic portrait of homelessness on record (“Marie”). However, other than nods to family (“Katie Belle Blue”) and friends (“Blaze’s Blues,” “Cowboy Junkies Lament”), all else pales. The mediocre “Gone Too Long” issues his last words. “I’ve been gone too long/Too long gone, too long,” Van Zandt sings. “Travelin’ hard, I just can’t get back home/It’s hard to believe I’ve done all that much wrong.”

Van Zandt’s recording career concluded with a fizzle. By No Deeper Blue (1994), he finally had earned a weathered and whipped voice for blues, but his most electric effort ironically lacked punch and substance. The album opens strong with two harrowing travelogues into darkness (“A Song For,” “The Hole”) and perhaps the most sympathetic portrait of homelessness on record (“Marie”). However, other than nods to family (“Katie Belle Blue”) and friends (“Blaze’s Blues,” “Cowboy Junkies Lament”), all else pales. The mediocre “Gone Too Long” issues his last words. “I’ve been gone too long/Too long gone, too long,” Van Zandt sings. “Travelin’ hard, I just can’t get back home/It’s hard to believe I’ve done all that much wrong.”

Ultimately, the songwriter baited demons for 52 years before dying at his Nashville home on New Year’s Day 1997. His impact spreads further with each passing day. “Townes was covered with more grace than about any human being that I’ve ever had the privilege of knowing,” says singer-songwriter Michelle Shocked, who crossed paths with Van Zandt at the Kerrville Folk Festival. “The gifts that he had and the inspiration he gave and received were truly spiritual gifts.”

Van Zandt’s was art ripe for posthumous renaissance, and recent history has obliged. Most notably, Texas songwriters Guy Clark (“To Live’s to Fly”), Billy Joe Shaver (“White Freightliner Blues”) and Steve Earle (“Two Girls”), among others, cherry picked from his cannon on the excellent Poet: A Tribute to Townes Van Zandt (2001). Additionally, the German compilation There’s a Hole in Heaven Where Some Sin Slips Through (2007), and British releases Introducing Townes Van Zandt via the Great Unknown (2009) and More Townes Van Zandt by the Great Unknown (2010) celebrate his legacy with a decidedly more askew approach. And in May 2009, Earle cracked Billboard’s Top 20 with his Grammy-winning tribute album, Townes.

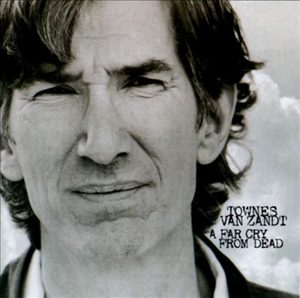

Van Zandt’s own greatest posthumous contribution remains A Far Cry From Dead (1999). A robust major-label collection culled from cassettes he recorded during his sober stretch in the early the ’90s, the album features buoyant full-band takes on greatest hits like “Pancho and Lefty,” as well as the studio improvisation “Squash” and the only recording of “Sanitarium Blues,” his chilling spoken-word reflection on time spent in mental hospitals. “Gigantic one-way gate ahead/You’re thinking, ‘Man I’d as soon be dead,’” he sings, sounding choked and corrupted. “They decide to give you life instead.”

Van Zandt’s own greatest posthumous contribution remains A Far Cry From Dead (1999). A robust major-label collection culled from cassettes he recorded during his sober stretch in the early the ’90s, the album features buoyant full-band takes on greatest hits like “Pancho and Lefty,” as well as the studio improvisation “Squash” and the only recording of “Sanitarium Blues,” his chilling spoken-word reflection on time spent in mental hospitals. “Gigantic one-way gate ahead/You’re thinking, ‘Man I’d as soon be dead,’” he sings, sounding choked and corrupted. “They decide to give you life instead.”

***

Quotes used in this column have been excerpted from writer Brian T. Atkinson’s forthcoming book, I’ll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt, due in 2011. The book features interviews with 40 songwriters, including Texas-born artists Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell, Jack Ingram, Kris Kristofferson and Lyle Lovett, as well as Scott Avett, Kasey Chambers, Jim James, Grace Potter and Josh Ritter.

MR. RECORD MAN’s TOP 5 TOWNES VAN ZANDT ALBUMS

1. Live at the Old Quarter, Tomato 1977

“Live at the Old Quarter is still the best Townes recording,” says Guy Clark, Van Zandt’s best friend and a legendary songwriter in his own right. Listen to the authority. Live at the Old Quarter captures Van Zandt delivering a seamless concert at the height of his powers. He’s funny, heartbreaking, inspiring. Hardly slurs a word. Unbeatable.

2. Live at Union Chapel, London, England, Tomato 2005

Two decades later, Van Zandt’s playing had grown muddy, his voice murky. Nonetheless, overwhelming heart and a deeper set list — with newer additions “A Song For,” “Catfish Song” and the “Still Looking for You”/“Dead Flowers” medley — makes this 1994 concert a perfect bookend to Live at the Old Quarter.

3. Flyin’ Shoes, Tomato 1978

Six years after his peak recording period, Van Zandt was mostly wasted and wasting. Flyin’ Shoes hardly shows it. In fact, the songwriter’s seventh studio album boasts exhilarating new work — “Dollar Bill Blues,” “Rex’s Blues,” “Flyin’ Shoes,” “Loretta” — backed by hill country musicians who clearly appreciate the poetry at heart. As far as his studio releases go, start here.

4. The Late, Great Townes Van Zandt, Tomato 1972

The Late, Great is essential for “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You.” Period. But don’t let those high watermarks overshadow nuggets like Guy Clark’s priceless (and otherwise unrecorded) slice of life, “Don’t Let the Sunshine Fool Ya,” or Van Zandt’s spontaneous “German Mustard.” All of Van Zandt’s earthy charm lies between the two.

5. High, Low and In Between, Tomato 1972

Van Zandt was called the Van Gogh of country music. See High, Low and In Between for proof. Songs like “Highway Kind,” “Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold” and “You Are Not Needed Now” radiate with absolutely singular landscapes. Absent a couple of “in between” toss-offs —the opening “Two Hands” and “Standin’” — this is all highs and no lows.

20 ESSENTIAL TOWNES VAN ZANDT COVERS

(In alphabetical order by artist)

1. “Waitin’ Around to Die,” The Be Good Tanyas, Chinatown 2003

2. “Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold,” Vince Bell, Recado 2007

3. “To Live’s To Fly,” Guy Clark (w/Emmylou Harris), Old Friends 1988

4. “If I Needed You,” Dead Ringer Band, Living in the Circle 1997

5. “Brand New Companion,” Steve Earle, Townes 2009

6. “Buckskin Stallion Blues,” Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Mudhoney, Mudhoney/Jimmie Dale Gilmore 1994

7. “Tecumseh Valley,” Nanci Griffith, Other Voices, Other Rooms 1993

8. “Pancho and Lefty,” Emmylou Harris, Luxury Liner 1977

9. “Snowin’ on Raton,” Robert Earl Keen, Gravitational Forces 2001

10. “Heavenly Houseboat Blues,” Christian Kjellvander,

There’s a Hole in Heaven Where Some Sin Slips Through 2007

11. “Flyin’ Shoes,” Lyle Lovett, Step Inside This House 1998

12. “You Are Not Needed Now,” Jonell Mosser, Around Townes 1996

13. “Snake Song,” David Olney, One Tough Town 2007

14. “Harm’s Swift Way,” Robert Plant, Band of Joy 2010

15. “Loretta,” John Prine, Poet: A Tribute to Townes Van Zandt 2001

16. “No Lonesome Tune,” Peter Rowan, Tree on a Hill 1994

17. “I’ll Be Here in the Morning,” Sid Selvidge (w/Amy Speace), I Should Be Blue 2010

18. “Dollar Bill Blues,” Shinyribs, More Townes Van Zandt By the Great Unknown 2010

19. “Where I Lead Me,” Eric Taylor, Scuffletown 2001

20. “No Place to Fall,” Steve Young, No Place to Fall 1978

No Comment