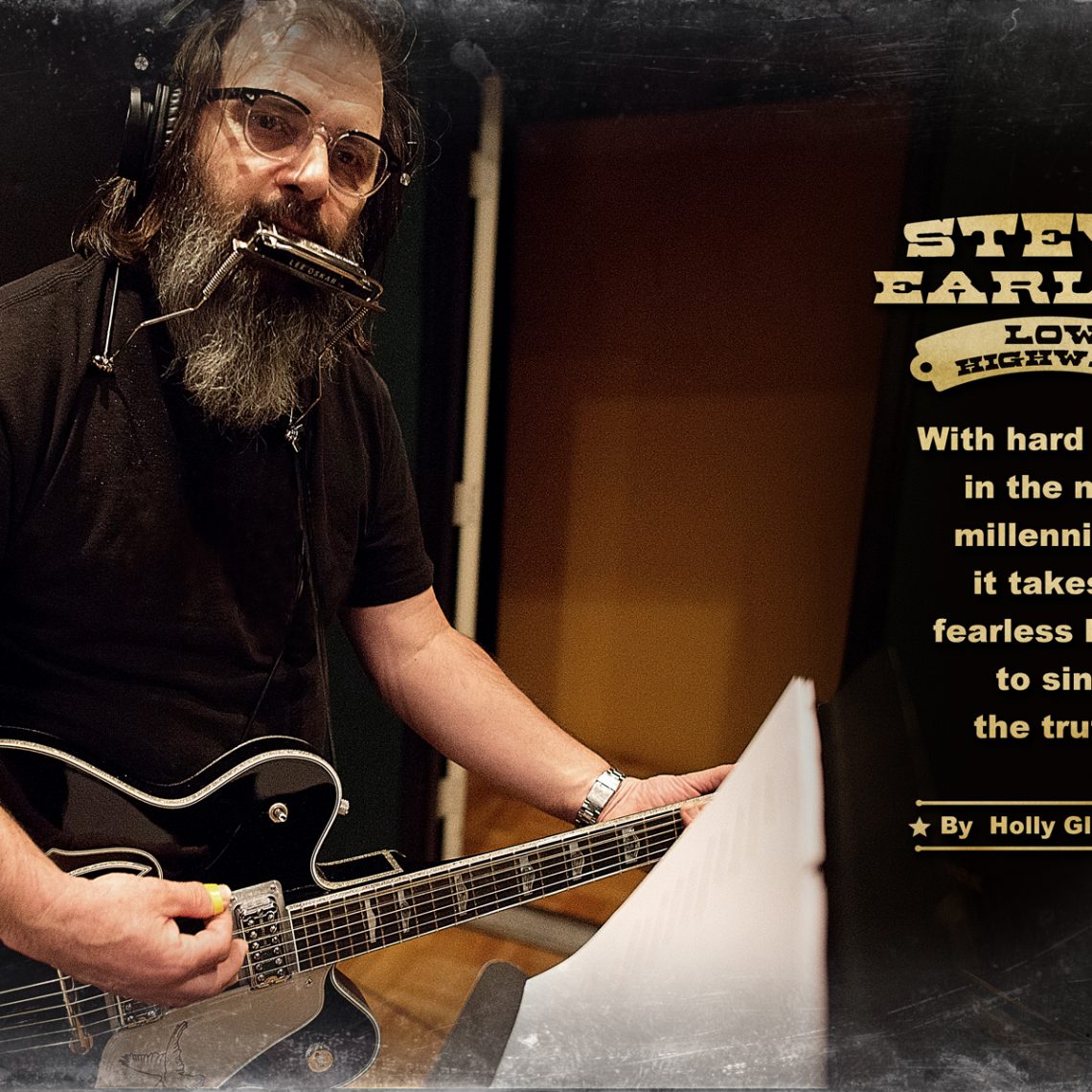

By Holly Gleason

(LSM May/June 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 3)

It’s a late afternoon in the Big Apple, the tail end of a particularly crazy day for roots-rock revolutionary Steve Earle. He’s back at his apartment in the Village following a run up to his other place in upstate New York, but realizes he forgot to bring back an instrument he needs to sit in with the Allman Brothers during their extended run at Manhattan’s Beacon Theater. And on top of that and the million other things on his plate and mind at the moment — or really, any moment — he’s also embarking on the promotional shuffle for his new album, The Low Highway. But the chaotic schedule seems to suit Earle just fine — just like New York City itself.

That biggest of all big cities might seem like an odd fit for Earle, who was reared a Texan and bathed in the troubadour waters of Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark and Mickey Newbury while scrambling around Nashville for more than a decade before coming to prominence as a post-modern rebel with his hand on the blue-collar/redneck pulse. But although he still owns the same house west of the Music City limits that he bought when success hit back in the ’80s, and spends a good portion of his time on the road, he’s embraced NYC as his adopted hometown ever since moving there in 2006. Manhattan’s energy feeds his restless soul and constantly racing mind. There is always something to do, someone to meet, somewhere to go, and for a man with a history as diverse as Earle, that is perfection. Because in the almost three decades since his 1986 debut, Guitar Town, the 58-year old songwriter/rocker has covered a lot of ground — literally, musically, and metaphorically. And he’s not slowing down.

The Low Highway is Earle’s 15th studio album, and the song cycle seems to be the perfect synthesis of all the musical styles he’s made his own since emerging as part of what he’s famously termed “Nashville’s great credibility scare of the mid-80s” (when acts like Earle, Rodney Crowell, Dwight Yoakam and Lyle Lovett all infiltrated the country charts). There is the gauntlet-tossing bravado of “Calico County,” a tale of meth-cooking that hammers harder than an 18-wheeler in the last 100 miles and pulses like Copperhead Road’s most rocking tracks. There’s the claw-hammered bluegrass of “Warren Hellman’s Banjo,” evoking Train A-Comin’ and The Mountain, as well as the progressive power-pop of “21st Century Blues,” which recalls the genre-melding of Washington Square Serenade and the anthemic urgency of The Revolution Starts … Now. And his soul-baring balladry — as heard on Guitar Town’s “My Old Friend the Blues,” Train a Comin’s “Goodbye” and I Feel Alright’s “Valentine’s Day” — is well represented with “Remember Me.” The song finds Earle considering the life he’s lived and what he has left to share with his youngest child, 3-year-old John Henry (his third, and first with his Oscar-nominated singer-songwriter wife, Allison Moorer.)

Earle’s diverse resume goes well beyond music, too. He has been cast as gritty, recovery-grounded characters on several seasons of HBO’s acclaimed The Wire and Treme. After hosting a politically-driven talk show on the now-defunct liberal radio network Air America, he continues his adventures in broadcasting with his Hardcore Troubadour Show on Sirius/XM. He has also written a New York Times’ best-selling work of fiction, I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive, as well as a collection of short stories, Dog House Roses, and is currently at work on a memoir broken into three pieces.

But for all of it, Earle retains his humanity, grounding himself as an artist of the people. His records are musically restless and deeply personal, yet somehow they hit the bulls-eye of what most Americans are trying to grapple with. It’s no coincidence that his perspective seems clearest and most alive when he’s looking out the window of a bus rolling down a two-lane, blue line highway somewhere in the fly over. That’s where he finds the truths, the characters, and the conflicts that have always forged his music. And that music has never been more relevant.

“I’m looking out the window, and I realize as I’m writing these songs, the songs are right now,” says Earle, not quite incredulous, but clearly aware of a shift in his creative reality. “I’m doing this job that was invented by Bob Dylan, who was doing it based on Woody Guthrie. That was his [Dylan’s] model — those songs from another time, from the ’30s, the Great Depression. Those stories and fairly romantic images are what draws us songwriters to it. But those things were real for Guthrie; for the rest of us, it was forensics!”

Not anymore, though. The Low Highway captures the decline of the American way of life in real time. Though never intending to core sample the failure of the American Dream, Earle realized soon enough during the early stages of writing the album that that’s exactly what it was meant to be, had to be. And once he gets started talking about it, look out: With a mind that fires faster than most mortals, he can corner, cut and dart at the speed of sound. Hanging on and keeping up with him over the course of an interview can be a challenge, but the passion that pours out is inspiring. It’s the rarest kind of conversation: unfiltered, to the point and to the gut.

“People are getting hit really hard, and it’s not a matter of bucking up or toughing it out,” he continues, barely taking a breath. “I was writing these songs, and suddenly it dawned on me: these songs … are … now! After I wrote ‘The Low Highway’ and had sung it a few times live, I realized I wasn’t writing about something that was. You could see it on people’s faces, and just passing through little towns more gone than alive on the business thoroughfares.

“So, this record for me is really looking at who’s left behind. Bruce’s last record (Springsteen’s Wrecking Ball) is about that, too. You’re seeing people generally writing about hard times, only it’s actually happening. We saw it coming 25 years ago. He and I saw it wasn’t trickling down the way it was advertised, saw it starting to happen. But now, its everywhere you look — and you can’t turn away.”

***

Earle has always written about the ones slipping through cracks, the ones unseen, the scrappy, the rejected, the losers and the lost. But he’s never been one to ply pity where dignity could do just as well, or better. Starting with Guitar Town, a brash roots travelogue examining the wear ’n’ tear of life on the road, Earle has chronicled the fate of the working stiff trying to get by. “I got a job, but it ain’t nearly enough,” he lamented in “Good Ole Boy (Getting Tough).” “Twenty-thousand dollar pick-up truck belongs to me and the bank and some funny talking man from Iran …” Or, as he railed in “Someday,” voicing the frustrations of a backwater kid working at an all-night gas pump: “You go to school and you learn to read and write/So you can walk into the county bank and sign away your life.”

Championing the people with their backs to the wall, making do somewhere beyond the margins, has defined the populist artist who’s worked hard rock, bluegrass, folk and country motifs over his 40-plus years as a songwriter and singer. But it’s also enlivened his songs in a way that exists beyond mere storytelling.

“I met Steve right when Guitar Town was released,” remembers Grammy-winning songwriter/once-upon-a-time country progressive Rosanne Cash, who shared manager Will Botwin with the tempestuous troubadour during the ’80s. “I heard the record and was totally smitten. It made me feel alive and excited and also … kind of passé. He was doing what I wanted to be doing. That record was just so rooted. It was cinematic, and literate and musically relentless. I loved it, start to finish.”

The Low Highway, Earle’s first studio album co-credited to his band the Dukes since 1987’s Exit 0 (and his first ever with the “(& Duchesses)” also in the name), leans hard into the truths no one really wants to talk about. Meth labs, post-Katrina New Orleans, the plight of the homeless, and the destructiveness of Walmart are all addressed head-on. With a bristling urgency, the songs are delivered with the precision live kinetics of a road-honed band that corners like a dream.

“Guitar Town was a road record, too, but it was a road record about me,” Earle explains, tracing his recording career from the very beginning to the present. “But I got lucky because people felt like those things I was writing about were about them. Like ‘Little Rock & Roller,’ which was about missing my son Justin (while touring), but you know, truck drivers miss their kids, too. So that kept it from being ‘Turn the Page’ — just being sorry for yourself because you’re riding around on a bus that costs more than most people’s homes, making music.”

Where Guitar Town was a record about the road, its follow-up, Exit 0, was literally born on the road — because Earle never got off.

“I had a publishing deal I could live off of, so I could keep taking the money from the road to pay for the bus and the band,” he says. “‘Sweet Little ’66’ and some of the earlier songs I was playing on the tours for Guitar Town were written out there on the road. Like that one and ‘The Week of Living Dangerously,’ we would hone them out on the road, come in and put ’em down in the studio, and then we just kept going. We were such a live band, just playing anywhere we could to try and build an audience. And we did.”

Twenty-six years down the line, Earle is still going, still taking in the American sprawl from the tour bus window. And far from being wearied by it, like the jaded journeyman rocker in that aforementioned old Bob Seger tune, Earle still embraces the opportunity to hit the interstate with songs and band in tow. As he enthuses in the liner notes for The Low Highway, “For me, there’s still nothing like the first night of a North Amercan tour … I’m always the last one to holler good night to Charlie Quick, the driver, and climb in my bunk because to me it feels like Christmas Eve long ago when I still believed in Santa Claus. God, I love this.”

But come morning, the view on either side of that low highway can be a harsh reality check. Beyond the adventure, it’s a searing reminder of just how much the American landscape has changed. And not, as Earle sees it, for the better.

“The road is not a pretty place to go now,” he concedes. “There’s way more shut-down stores than there used to be. They’ve been shutting down factories for years, but now it’s the towns themselves. We take a lot of blue highways, drive through a lot of smaller towns as well as cities, and when you see more than two nail salons and boarded-up businesses in a strip mall, you know how bad times are. And that’s all you see now.”

With The Low Highway’s “Burnin’ It Down,” Earle doesn’t mince words when it comes to identifying who he sees as one of the main culprits.

“Walmart in a town of 10,000 really does damage,” he says. “You’ll see a Walmart going up, and know it’s only a matter of time. Because Walmart, with their sub-minimum wage jobs — or they’re minimum-wage jobs, but they’re not 40-hour jobs, and there are no benefits -— that’s why there’s more meth labs now than mom ’n’ pop businesses.”

Earle pauses for a moment. He’s a talker, and he knows it. But he’s a thinker, and chances are what falls from his lips has been weighed twice and measured accordingly. Though he dropped out of high school because the redneck jocks kept chasing him down and cutting his hair, the son of a Houston air traffic controller is one of the better-read people you will ever meet. That sense of history, literature, and the mechanics of living informs his work and words with a vengeance.

“I wrote ‘Burnin It Down’ really, really early, and it maybe set the tone (for The Low Highway) without me even realizing it,” he continues. “On the surface, it’s a song about a guy who’s turned his car into a bomb, and he’s about to drive it into the wall of a Walmart, blow the thing sky high. But, really, there’s a choice you have to make… and that’s beneath the story line. Listen to it. It’s really about jobs versus bigger and cheaper flat screen TVs; paying people a living wage so they can exist with dignity, or else slip into what is rapidly becoming a third-world country. It comes down to that. So many people we don’t see because they’re in these small towns, and they’re suffering because our economy is now flipping burgers and parking cars and making change, because the factory jobs and the small local businesses are falling away and that’s all that’s left.”

A loping acoustic guitar scape, driven by a muted kick drum and the occasional electric guitar sprinkle, “Burnin’ It Down” is subtle. Though not quite a prayer or a lament, there’s a meditative quality to the song, which is delivered in the most worn part of Earle’s voice. Exhaustion permeates, and as the melody moves along, there’s a hint of organ and a cloud of accordion to pull the listener even closer. But the lulling, pastoral feel sucker punches the listener with a message that strikes like a sock full of quarters.

“Have you heard that song Steve wrote about blowing up the Walmart?” marvels country siren Patty Loveless, on the phone from South Georgia. “That’s sure Steve. Cause, you know, there are a lot of people who feel just like that: So mad, and they don’t know how to say it, or get heard. And they don’t have to, ’cause Steve Earle will do it for ’em. Steve knows, and he’s not afraid to write about that stuff from a very real place. He doesn’t sugarcoat it, he doesn’t make it something it’s not — and that scares people!”

As a girl from the holler whose family moved to the city to get her father better medical care for the black lung disease that would ultimately kill him, Loveless understands the people left behind by the American Dream from a very really place, too. And she’s known Earle for years, going back to when they were both first starting to test their wings, two kids tilting at the very sugary pop-country status quo. She ended up cutting an Earle song on each of her first two albums — “Some Blue Moons Ago” on her self-titled debut, and “A Little Bit In Love,” her first Top-5 hit, on 1988’s If My Heart Had Windows.

Earle crashed the country charts in the ’80s, too, but he was not long for the mainstream.

“He knew no fear, and he just kept going,” Loveless says admiringly. “He was a rebel, you know? A real bad boy, but in that Waylon Jennings outlaw way. Or a Kristofferson type of person: the songs before everything. And they better be real, or he wasn’t interested. He’d fight for that. And yet, it wasn’t fighting to fight — it was for the sake of his music.”

***

By the time Earle saw his MCA debut climb to No. 1 on the country album chart, he’d already been fighting for the sake of his music for over a decade. He was still a kid when he landed in Nashville in the mid-70s, just another scrapper from Texas who dreamed in songs and found his way into the circle of maverick writers and pickers orbiting around the Townes Van Zandt/Guy Clark/Mickey Newbury nucleus. He banged around as an acolyte for Van Zandt, played bass for Clark and found himself a publishing deal, but it was still years — and a shelved rockabilly-infected album for CBS Records — before he saw things really click into place for him. And a while after that before he actually believed it.

“The thing about Guitar Town is, I was so glad to have a record deal, and I made that not knowing if there would ever be another one,” Earle says. “After working for a real long time, and not knowing if there’d be another one, I was gonna make it count! I’d been in town for 13 years at that point, and nothing had happened. So, there was no reason for me to think it was going to be anything else. I mean, Tony (Brown) signed me, Lyle (Lovett) and Nanci (Griffith) around the same time, because he believed singer-songwriters were going to be the next big thing. But I had plenty evidence to the contrary — with 13 years in town and nothing to show for it.

“And it wasn’t cause I was getting fucked up then,” he insists. “The drugs were never the issue — it was that people didn’t want to hear it on country radio. So I dug in, made the hardest truth records I could and went out to find an audience … and then accepting who my audience was.”

In that search, Earle found palpable inspiration. Having come of age when there was a strong distrust between the Suits (the Music Row hierarchy) and the Creatives (the songwriters who were truly striving to distill human experience into three-minute songs), the dark-haired Texan wasn’t someone people on 16th and 17th Avenue wanted to see in daylight hours. But that outsider reality added fortitude and heft. To the present day, it’s what has made Earle a bit of a lightning rod for the conservatives who pay attention and a rallying voice for liberals looking for someone and something a little less elite to speak to their cause. Just as importantly, Earle spoke for a group of people desperately needing someone to speak for them — though it wasn’t as simple as bullet-point historians would make it.

While Earle seemingly exploded after his debut, with features in Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Newsweek and The Los Angeles Times, mainstream country — the purview of “working people,” especially of Southern or Southwestern descent — wasn’t buying in. And if Earle wasn’t going to be the salvation of progressive traditionalism, there was a gap to negotiate, a backlash to mediate and an audience to coalesce.

“There are still people who are angry about that record,” he says, “because I wasn’t what they thought I represented myself to be — some new traditionalist movement that was gonna save country music. Robert Hilburn (The Los Angeles Times’ premier music critic) thought I was reinforcing the idea that country music was art. But that wasn’t my deal at all. I never wanted to be George Jones. Johnny Cash maybe, but not Merle Haggard. That’s just not my deal. I wanted — like so many of us — to be Bob Dylan, to come from that place. But people thought I was something I wasn’t, and then they were mad at me for that.”

In some ways, it did Earle good. The disaffection of the place that launched his career, as well as his increasing drug use and a dyspeptic personal life, made Earle feel even more resolved about following his muse. For his third album, 1988’s Copperhead Road, he walked into Ardent Studios in Memphis and leaned full bore into a much heavier sound. While Lone Justice’s Maria McKee joined progressive bluegrass group Telluride for the closing Christmas hymn, “Nothing But a Child,” the barreling title track at the other end of the record became a rebel anthem for a group of outlaws seeking an alternative fiscal reality. A whole new, wider audience of rock fans found Earle, but it wasn’t long before he realized their expectations could be just as constrictive as country radio.

“The Copperhead Road audience who hadn’t heard Guitar Town and Exit 0, they wanted me to be Lynyrd Skynyrd — and that wasn’t gonna happen, either,” Earle says. “I went through this period of trying to find an audience where I was comfortable: being the right amount of loud, the right amount of intense … because I was always too much that for Nashville. And over time, I realized my audience really is the people who wanted to watch me go through these changes, and pay to experience it with me. They were there for the journey, and they were curious about what was next.”

Still, the Copperheaders were an insistent bunch, hell-bent on deifying the song’s rebel dope growers who sprang up in the stead of their moonshiner forebears.

“I think some people heard ‘Copperhead Road’ and thought it was about how cool it is to be a redneck, or an outlaw redneck,” Earle marvels. “They didn’t get that ‘Copperhead Road’ is kind of a parody. It’s a parody of Toby Keith and all those people who play that kind of attitude. It’s supposed to be real desperate: this is someone who only has this left. I made it as ugly as I could, and no one got it. They just thought it was cool. But it’s about handing down this horrible way of dealing with poverty. They made moonshine, then they grew marijuana back in the hollers. Now they cook meth. It’s a horrible evolution.”

As a man who’s journeyed through his own twisted path of addiction — descending into what he has referred to as his “two-year vacation in the ghetto” as his addiction to crack spiraled out of control, as well as eventually doing time for possession — Earle understands the stakes. “CCKMP” (“Cocaine Cannot Kill My Pain”), from 1997’s I Feel Alright, painted the harrowing truth about the lessening effect of drugs as one’s habit progresses, while “Oxycontin Blues,” from 2007’s Washington Square Serenade, got real about the encroachment of the high-powered painkiller.

On The Low Highway, Earle returns to the motif of generational making-due in the lesser economic brackets. “Calico County” expands on “Burnin’ It Down”’s back-to-the-wall frustration with the blind bravado that comes with living outside the law. With a piston downbeat and a buzzing guitar, Earle opens the song by spitting out the recipe for cooking meth: “Half a case of cold pills soakin’ in a milk jug/Hydrochloric acid iodine and phosphorous/Careful not to get any on ya when you shake it up.” Disturbing as that matter-of-fact description is, though, the real jar comes with the second verse’s window into a world that most college-educated people will never see. Plowing through the raucous track, Earle spells out the facts of his character’s life:

“Born in a double wide out behind the county dump/Mama never told me why Daddy didn’t live with us/Only picture I had he’s climbing on a prison bus/Stencil on his back said Calico County …”

There’s no judgement, just a picture that speaks volumes about what happens when people fall into cracks that have become canyons.

“When crack hit, no one was prepared for it,” Earle recalls. “It was so cheap at the entry level, you didn’t see it coming — and so addictive, you couldn’t imagine. I started smoking crack after shooting dope for years. That’s when the wheels came off pretty quickly. Meth is pretty much the same thing, the momentum of it: you can’t prepare yourself. You just can’t. And it takes everything away. But it’s so easy to make, to get … people start cooking meth, doing it to escape the hopelessness. That’s how it starts.”

***

Earle may have been trapped in a no-man’s land between genres — too rough for country, too twangy to fit in the Guns ’N Roses realm of rock, and too much of a genius to ever make it in pop — but he found out the hard way that drugs didn’t discriminate. His addiction cost him his teeth and landed him in jail after several stints at rehab failed to get him on the straight and narrow. While his hardcore talent remained undisputable, the question around Nashville was “Have you seen Steve Earle?” The answer was usually a blank stare or a guilty look. But once he found himself in jail, he took a good long look and realized what a waste he’d become. Though he’d joke that you know you’ve got a problem when they send Townes Van Zandt to do an intervention, it was time to get real. And like everything else in his life, once Earle makes up his mind, there’s a singular focus that never looks back.

Emerging from prison, he made two world-class albums in rapid succession. The expectant bluegrass-leaning Train a Comin’ was followed by the hard-charging I Feel Alright, a swaggering spew of vitrol at the people who counted him out and a declaration of how exultant his truth was. Establishing his own E Squared Records imprint gave him the freedom to follow his muse, and the MTV To Hell & Back concert special, filmed at the Cold Creek Correctional Facility in Henning, Tenn., gave him street rock ’n’ roll cred and serious badass bone fides.

But Earle was more than a rocker taking corners on two wheels. For 1997’s El Corazon, which merged Train’s acoustic tenderness with Alright’s intensity, he enlisted a diverse roster of guests in the Supersuckers, the Del McCoury Band, and the Fairfield Four, and tipped his hat to Van Zandt in the hushed “Fort Worth Blues.” The opening “Christmas in Washington” also foreshadowed his determined move into the areana of politically charged folk songs by pulling back the curtain on special interests.

Earle emerged not just better for the wear, but strong in his resolve. In addition to helming his talk show on Air America, he became a committed activist, campaigning against capital punishment and protesting the Iraqi War with Cindy Sheehan. And he hasn’t shied away from expressing his convictions in song, either. Indeed, after his entreaty in “Christmas in Washington” — “Come back, Woody Guthrie!” — came up empty, he realized his voice was going to have matter. “Billy Austin,” his death-row lament from 1990’s The Hard Way, may have been his most overt political statement prior to his jail stint, but since then he’s held nothing back, resulting in some of the most powerful (and at times controversial) songs of his career: “Ellis Unit One,” “City of Immigrants,” “Jerusalem,” “Rich Man’s War,” and of course, “John Walker’s Blues.”

“His activism truly comes out of compassion and a strong sense of justice,” observes Cash. “It can’t help but infuse his world because that’s who he is. He has a very rare gift, which is the ability to write a socially topical song, a protest song in the perfect sense, without proselytizing. That’s very hard for me. I’ve had very little success with that. But Steve is brilliant at it. I think ‘Jerusalem’ is one of the greatest anti-war songs ever written.”

There is no doubting that Earle, less of a pop culture lightning rod than a thinking man’s siren, has put his time to good use. In the 21st century, he has published Dog House Roses, a book of short stories, and I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive, a novel about the doctor who gave Hank Williams his final shot and is now working as an abortionist in a border town. And his albums since El Corazon have found him confidently leaping from majestic Beatlesque pop (Transcendental Blues) to traditional bluegrass (The Mountain with the Del McCoury Band), strident protest rock (Jerusalem and The Revolution Starts … Now), spare techno-folk (Washington Square Serenade) and an entire album of Van Zandt songs, Townes.

And now there’s The Low Highway, a project that reunites both the Earle/Ray Kennedy production team known as the TwangTrust and the Dukes (& Duchesses). Among the Duchesses is, of course, his wife Moorer, who is prominently featured on the particularly feisty junker, “That All You Got?” Inspired by New Orleans’ staying power in the face of near complete devastation, it’s metaphorically sound for the relationship between two highly combustible creative people.

That combustion is what fires Earle’s albums: the conflict between what is and what we tell ourselves. Beyond “Calico County” and “Burnin’ It Down,” Earle recorded a trio of songs he wrote for HBO’s Treme — “Love’s Gonna Blow My Way,” “After Mardi Gras” and “That All You Got?” — that evoke the post-Katrina reality of a city still struggling to reclaim its former state of operation. There is also the tugging witness of the homeless in “Invisible,” and the newer-isn’t-always-better, progress-at-what-cost indictment, “21st Century Blues.”

“I always want people to pay attention,” Earle says. “I only make the record I can make: where I am and what I’m experiencing. I wrote ‘John Walker’s Bllues’ because nobody else was going to — and because it needed to be said. But that’s not something I set out to do. Even here, I was making this record when I realized how ‘in the moment’ it was. Maybe writing those songs for Treme, for a show about New Orleans, really focuses on a larger thing.

“The story of New Orleans post-Katrina is really a canary in a coal mine, but the reality is there’s still all these things that all these years later are still broken,” he continues. “Not because people don’t care, but because of fiscal realities. New York after Sandy’s the same thing. There’s more money and more white people there, but it’s the same deal that no one wants to talk about. We as a country don’t recognize or accept that we don’t have the funds to fix this stuff back to how it was. The measure of who we are is how we handle this kind of stuff. We weren’t prepared enough and didn’t care enough (after Katrina) to have an infrastructure in place. Or even a plan. So, Sandy was a mess! There was no electricity in my neighborhood for six days, but we were high and dry. I had a photographer friend in West Beth, the artist community on the West Side, who lost his entire life’s work from the flooding. In New York City! That’s reality … and it takes money to be ready.

“It’s finite. You can’t take over the world and lower taxes,” Earle continues, pulling out of the micro and making the larger connections. “The Romans, the Brits and the Germans: they all tried to take over the world and they all raised taxes, too. So you have to give us credit for originality, but it ain’t gonna work! When a crisis arises, you have to face the facts of what you don’t have. It’s just like the schools: teachers aren’t the problem in our education system, it’s the lack of funding. But if you can blame the teachers, no one will look at the real issue.”

At a time when much of America is narcotized by the Kardashians, various groups of entitled wives behaving Marie Antionette-ishly and the ignomious Honey BooBoo, Earle rues the erosion of America’s intellectual striving.

“I’ve never seen Honey BooBoo,” he says. “But I feel pretty sure it’s not good for me, so I’m not gonna look at that! Other than a bit of the first season of Cops and part of an episode of Survivor, I’ve never watched any reality TV. In a very, very unhealthy way, it’s addictive. You don’t want it, but you just can’t turn away. It’s sick. Like in jail, everybody has to think they’re better than somebody else. It’s human nature, and reality TV is the same thing! In jail, the people you looked down on tended to be sex offenders, especially if there was any hint of a child being involved. After 9/11, it became anyone considered ‘other worldly,’ because they were easy targets to scapegoat. But think about that, because (the reason people watch reality TV) is the same thing.

“The greatest writing of this age is being done for TV. So there’s no excuse to be watching all that crap. There just isn’t, and yet … We get the democracy we deserve, just like we get the music we deserve.”

It’s not about being an elitist; it’s about the unfair way the table is getting stacked. It’s part of what informs how he lives. For The Low Highway, an album that merges his roadhouse swing with the more acoustic post-folk/bluegrass leanings, it tempers the songs. Though not one to preach, he’s not apologizing for his most taut musical wake-up call to date.

“We are so brain washed to believe Wall Street is the indicator. We’ve bought into this notion of trickle down, but there isn’t any. It’s pretty simple: people are going to lose their jobs, because those folks on top are going to protect their profit margins at all costs. If that includes eradicating those people doing the jobs, well, it’s the cost of doing business.

“And nobody’s paid for what happened by putting the economy in the ditch! The people responsible for the sub-prime mortgage crisis? They were rich before, and they got richer after. It was the people who were beneath them who went to jail, the few who did go, and the people borrowing who lost everything. Capitalism is not a religion or a philosophy. It’s not, and that idea that the market will ‘take care of itself’ is not true. So what we’re doing now is co-signing the same bullshit for these people who caused all these problems and weren’t punished. Now they’re brokering the bankruptcy of our way of life.

“It comes down to some pretty basic stuff,” he says. “Everybody wants to believe they’re okay, and that’s perfectly understandable. You want to believe that, and that people are basically good. But that’s the trap. Just because I’m okay. It doesn’t mean (any of this) is okay. The only way we’re going to get better or out of this is to start really caring about each other. And that means caring for all of us.”

It’s interesting that this is the record where Earle reactivates and expands the Dukes with the Duchesses. Longtime rhythm section Kelley Looney and Will Rigby are supplemented by Moorer and the husband and wife team Chris Masterson and Eleanor Whitmore (who also perform as the Mastersons). By bringing so many familiar elements together, there’s an almost telepathic connectivity to the performances.

“Whether it was so much a conscious decision, I don’t know,” he allows. “I never disbanded the Dukes. There’d been Eric Ambel, who’d been added after the fact. The rhythm section was pretty consistent. Chris and Eleanor had been in Allison’s band before John Henry was born — and Chris had always sort of been in line for the gig actually. But Washington Square took me somewhere else; that was me with a DJ on that tour. Townes was just me and a guitar. Then I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive came along, and it needed a bigger band than I’d been carrying. It was like pulling teeth to get Allison to play keyboards, but she did. That band was very special. You could tell from the moment when we first started. And I toured with them, and through all that, I felt like it was a band that deserved an album.”

It was also a band that could reinforce Earle’s low pilot light intensity. Whether the jaunty “That All You Got?,” the jazz perk of “Pocket Full of Rain” or the jangle pop of “21st Century Blues,” the loose grooves lend a certain freewheeling potency to the tracks. Even the straightforward acoustic strumming that grounds “Invisible” has an elegance to it that is equal parts head-held-high protest and marching towards the truth.

“I started ‘Invisible’ for the last record, but then figured it needed to be part of a different kind of record,” he says. “Then when this started coming together, I knew. This is about people in my neighborhood; this one literally is right outside my window. There’s a Catholic Church 50 yards from my front door, and I walk by it every day on my way to the gym. There’s a soup kitchen there now. You see ’em lined up every day — those long, long lines with people coming out with Styrofoam cups of coffee and containers of food. Tim Robbins was an altar boy there when he was growing up. He came from this neighborhood, so that was his family’s church. I was telling him about the soup kitchen, and how many people were coming to it. He said, ‘No, there’s always been a soup kitchen. We’re seeing it now because the lines are so long. You can’t miss them …’ That hit me. People had always been getting fed at this church, just when it wasn’t so many you didn’t see them.

“How we treat the less fortunate says a lot about who we are,” he continues. “I believe Walt Whitman was right when he said, ‘I give alms to anyone who asks.’ Now I may not give them a lot of money… and they may go blow it on drugs, but I help out where I can, do what’s possible. But even more than money, those people notice when you look through them. They know you’re choosing not to see them. They can tell, and they don’t like it because it’s like they don’t even exist. Think about that: choosing not to acknowledge someone’s humanity.

“I just know I want to acknowledge the people, show them they’re seen.”

A basic human need. A simple gesture that costs nothing. The reality is stark, but the solutions can be pretty simple. He sees that inspirational part of what his music can do as part of the legacy of a song’s power.

“Steve’s activism, his humanity and his lyric sense … it’s all of one piece, all Steve!” Cash enthuses. “His heart is huge, and his rhyme schemes are perfect. He ‘contains multitudes.’ He’s like a kid in some ways — excited and excitable, passionate and obsessive, always a beginner.”

***

Today in Manhattan, Earle is as close to at rest as he can be. There is still the gym, still work on his memoir, still songs to rehearse or write. As accomplished as he is — and he has three Grammys to validate his music — it is always about the next song and the next show on the horizon. He admits there is a certain drive, a chasing what can be as an artist, that matches his commitment to civic concerns.

“Everyone who followed Mickey Newbury to Nashville, it goes all the way back to that,” he says. “Tom T. Hall, Hank Cochran, Willie — they all know you have to be smart to write those kind of songs. Kristofferson was a poet! He wanted to be Dylan, to write songs that were more. D.A. Pennebaker just showed me this footage of Kris in a room in Greenwich Village. Odetta, Bob Neuwirth, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot all were there. He had maybe a few songs out, but it was before anyone knew who he was, before he played the Newport Folk Festival, before Bobby Neuwirth introduced him to Janis Joplin and he played her ‘Bobby McGee’ …

“You watch that,” he continues, “and you can tell he was about the art and the poetry of songs, the truth with them. You can invent a new name every 10 years — country rock, alt-country, cow punk — but it’s not new. It doesn’t replace songs, or what’s great. That’s marketing, not music.”

That all-about-the-art/for-the-sake-of-the-song aesthetic has moitivated Earle throughout his entire career. It’s as much a part of what defines him as the independent spirit that propelled him to leave Texas at 19 and never go back for longer than a visit — even though he still acknowleges his Texas roots. And not without a certain amount of pride.

“It’s a cult, you know, that all started around Townes,” he continues. “Guy Clark’s part of it, Rodney Crowell, Lucinda, even Mickey Newbury. Nobody ever goes back, but you’re always a Texan. Even if you don’t live there, it’s always in your blood … It’s something in you. When I got to Tennessee in 1974, you wouldn’t have recognized me out of my cowboy clothes. Rodney and Emmylou did my radio show recently, and Rodney asked me about my old black cowboy hat. I said to him, ‘The last time I saw that hat, it was going west on the grill of a Peterbilt and I was heading east, hitchhiking back to Nashville after going home for the holidays.’ That’s how we all were.”

Earle knows that it’s his roots that make him strong. And that sense of tradition is something that he’s passed on to all three of his sons. Although Justin, Dublin and John Henry were all born miles from the Lone Star State, Earle made sure the first soil they ever touched was from Texas. Just like when Earle himself was born in Virginia, he had dirt sent up from the family farm in a tobacco can and pressed the newborn’s feet into it.

“It came from my grandfather’s farm,” he explains. “My cousin lives there now, so that was the first dirt my boys ever set foot on. Those traditions are important. It’s who we are.”

“That’s Steve,” Loveless marvels. “Beneath all that tough-guy exterior, he has a real soft place.”

“He’s a humble guy,” adds Cash. “He’s scraped the bottom and knows how it feels. He knows time and health are precious. I’ve been so pissed at him at times, put-off by the manic stuff, angry that he didn’t show up for work when he was using … but I have the most tender spot for him. He’s a huge soul. I love him.”

Earle has, as Cash points out, lived a lot of life. Some of it reckless, wanton, even pointless, but always there was that need to return to something heftier, something that spoke more, that called attention to what really mattered. He was never a badass to show someone how tough he was, just as he didn’t protest to get his liberal hip ticket punched. He saw, and he wanted to share. Along the way, he went places that were dead ends, but he always, always found his way back. And after all these years, he’s still out there hitting the low highway, eyes wide open. Because there’s a lot he still wants to see, to say, to do.

“There were four of us who left school at the same time,” he says, looking back. “I’m 58 years old now, and the only one left. Nobody’s would’ve bet I’d be the last one standing, the one who’d survive, but I am.”

No Comment