By Holly Gleason

(LSM Jan 2014/vol. 7 – issue 1)

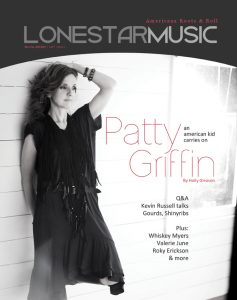

Patty Griffin swings open the door to her tour bus, far heavier than it looks, with a tangle of wavy mahogany hair tumbling down her shoulders. The bus is parked in a lonesome alley behind an historic old brick hotel, and the day is grey, if not quite raining, but she refuses to let the weather dampen her spirits.

Behind her, a short-legged black dog with a snowy muzzle and the rest of her coat turning ashy from age looks up, tail wagging, barking, making her presence felt. Looking down, Griffin sighs. “It’s her last time on the road, and the hotel’s not particularly dog friendly ….”

Last times for old dogs are hard. Harder on the owner, often, than the best friend. And Griffin, whose spring release American Kid was highlighted by a song called “Wild Old Dog,” is clearly intent on savoring every moment with Bean. The slow-moving mixed breed is as at home on the road as an old-school roadie, accustomed to curling up in her own bed onboard the bus in the cozy, caramel-colored front lounge and falling fast asleep to the gentle hum of the generator.

Not all old dogs have it so good.

“I used to drive back and forth from Nashville to Austin,” says Griffin, a critically adored solo artist whose songs have also provided seminal moments for the Dixie Chicks, Kelly Clarkson, and Emmylou Harris. “And I remember seeing this beautiful, beautiful dog out there on the highway, and it didn’t hit me at first, but … who could do that? It’s cowardly, to do that to an animal you’re no longer willing to care for, who loved you no matter what. Even homeless people have dogs …

“I kept on thinking about that dog for years,” she continues. “The story about that dog and how he got there. Pema Chödrön, this American Buddhist teacher, was talking about the Dark Ages — how we’re in one now, where people can just look past such suffering without even noticing. I think about the woman’s voice with that man who’s not having any of it, that feeling of powerlessness.”

It’s the heart and the soul that matters to this slight woman with deep, chocolate eyes; she is not about the shiny, the glossy, so much as those things that endure, that notion of feeling broken but not surrendering, and that flicker of light that shines through. Those are the things that mark the tough ’n’ tender portraits that anchor the songs she writes, the emotional upheavals and arrivals, the scenes so real you can sniff them on those melodies, both delicate and surging.

“I think her music taps into something primal, and I base that statement on the way I’ve seen other people react to her songs and her delivery,” says New York Times best-selling author and Berea College’s Appalachian Studies chair Silas House. His next novel, Little Fire, is interwoven with Griffin’s songs. “There is something about Patty Griffin’s music that is so relatable and full of emotion without being sentimental or saccharine. She captures the joys and sorrows we all have, not only in her careful and luminous songwriting, but also in the careful turns of phrase she has with a single word or syllable.”

Cameron Crowe, the rock journalist turned Oscar-winning filmmaker, also finds inspiration in her music and her being. “Patty writes with such tenderness, depth and soul; her work is filled with purpose and melancholy and the chips-fall-where-they-may language of a truth teller,” Crowe enthuses, calling Griffin “a beautiful ache, like a trip through your old hometown.”

“Her songs make me wish there was a theater playing the films of her songs 24 hours a day,” continues the writer and director, who cast Griffin in his 2005 movie Elizabethtown as a mostly silent local. “She was a wonderful presence on film. In the few scenes we filmed, it was clear she’d be exactly as you’d imagine: charming and enigmatic, a personality filled with deep blues and electric reds, and as quietly unforgettable as her music. ‘Long Ride Home’ was a big inspiration for Elizabethtown, so I was blown away to have her on my journey.”

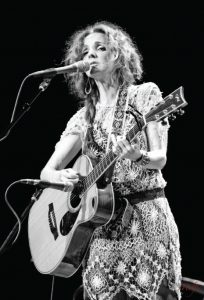

In less than three hours, this woman revered by writers, critics, filmmakers, fellow musicians, and thousands of passionate, discerning music fans the world over will take the sold-out audience at Louisville’s Brown Theater with her on another journey, sharing songs from throughout her life and career that most of them no doubt already know by heart. Before that, she will sit for an extensive pre-show interview tracing the topography of that life and exploring what these songs and recordings are made of, continuing a conversation started over the phone several days before.

But first things first. Like the songs she writes, Griffin’s life is defined by loving, living moments, small details, and tiny gestures, like the way she steps off the bus and into the cold that goes through the bone without a hint of annoyance. Dog leash in hand, she smiles and waits patiently for her dear old companion to make her slow, waddling way out to join her. Press, fans, and the rest of the world can wait. Bean has to tinkle.

* * *

Little Beanie’s impending retirement from the road comes at the tail end of a very big year for Griffin. May of 2013 saw the release of her widely acclaimed American Kid, a deeply personal album inspired by the loss of her father and recorded at the late Jim Dickinson’s legendary Zebra Ranch Studio in Mississippi (with Dickinson’s sons, Cody and Luther of the North Mississippi Allstars, providing the rhythm section). Five months later, American Kid was joined on shelves by a second new Griffin album — or rather, a new old Griffin album: Silver Bell, her almost mythic previously unreleased third album, was finally made commercially available after 13 years in record company limbo.

The reaction to both albums — by critics, fans, and peers alike — has been, to put it mildly, effusive. And although American Kid was overlooked for a 2014 Grammy nomination, Silver Bell (released on Oct. 8, just after this year’s deadline) will still be eligible in 2015. Of course, Griffin is already a Grammy winner, having taken home a Best Traditional Gospel Album Grammy for her last album, 2010’s Downtown Church.

Downtown Church won Griffin more than just a Grammy, though. After the album’s completion, producer Buddy Miller enlisted his longtime friend to be a part of his next project, the roots supergroup Band of Joy anchored by Robert Plant. Griffin sang back-up vocals on Plant’s 2011 Band of Joy record (the Americana Music Association’s Album of the Year) and toured with the band for almost two years. (Not coincidently, Plant can be heard singing back-up on American Kid’s “Ohio.”)

All in all, it’s been a whirlwind four years. But the first 14 years of her recording career were quite a ride, too. The Old Town, Maine native was 32 years old when she burst onto the scene with her 1996 debut, Living with Ghosts, on A&M Records. A beautifully unvarnished demo in all but name, Ghosts was comprised of stark, almost scrawled-line drawings sketching the abused and overlooked. But dignity imbued her characters, existing on the margins but hopeful in spite of it all, and her voice was an amalgam of fire, dank shadows, and old clay that seemed culled from the earth’s very core. When you heard the papery whisper of the have-not’s lullaby “Poor Man’s House,” the supple, velvet sass of “Time Will Do the Talking,” the brandy ’n’ desire of the steadfast “Lorraine,” and the taunting blues pushback of “You Never Get What You Want,” you knew this was a woman of substance. Her ability to seek such colors and textures with her voice — and use an acoustic guitar like a buzz saw, battering ram, or angel wings — suggested something more than a mere spinner of stories and singer of songs.

But the songs could fly on their own, too. Living with Ghosts was more of an underground than commercial hit, but early fans the Dixie Chicks covered the album’s “Let Him Fly” on their industry-shaking 1999 blockbuster Fly, showing the universality of Griffin’s singularity. Her songs were for the faithful and the masses.

When the Chicks hand-picked her as one of their opening acts on their Fly arena tour in 2000, Griffin had a second record of her own to promote — and a suitably loud one, too. Flaming Red (1998) was a churning, raucous affair, as fierce and assertive as its predecessor had been spare and haunting. Jay Joyce’s production moved from the whirling cacophony rock of the title track to the carnival lurch of “One Big Love,” with Griffin’s voice cresting like foam on a wave, inviting and silken on the thick wads of guitars, sheets of keyboard, and pillows of bass notes. The surging “Wiggley Fingers,” with its Hendrix buzz and seismic bottom, threw down an acidic challenge that chilled to the bone, while the murky torch of “Go Now,” equal parts Mule Variations Tom Waits and cocktail-era Sarah Vaughan, suggested an odd timelessness of desire amongst the less than beautiful.

Most devastating of all, though, was “Mary.” Steeped in the beautiful angst of maternal sacrifice, every line a perfect image of the wages of motherhood or a truth about the Blessed Virgin, the song still looms large over Griffin’s canon. Although now known as an austere ballad, Flaming Red’s rendition is embroidered with electric guitar and basted in Springsteen-evoking B-3, with a low rumble of tribal drums communicating the primordial truths Griffin sweeps up in her almost exhaled evocation of every Catholic girl, lapsed, faithful, or not quite sure.

“She’s quite the novelist,” Joyce observes. “She’s also the best singer I’ve ever worked with. You can’t cover her range: she has the lowest, airiest notes to this high note you can’t even describe. And you don’t feel like she’s even working at it.”

Griffin’s roar on Flaming Red was deafening. The sales were not. But with her buzz still growing, she entered Daniel Lanois’ Kingsway Recording Studio in 2000 to work on the follow-up with the confidence and momentum of an artist poised for a breakthrough.

And that’s when — note when, not where or how — the trouble began.

In the age of corporate mergers, staff consolidations, and “smarter business models,” suddenly A&M Records, whose initial support of Griffin was in keeping with its history of developing careers for such singer-songwriters as Suzanne Vega, Joe Jackson, and Sheryl Crow, was absorbed into Interscope Records, the Jimmy Iovine-led temple of hard rap, U2, and Nine Inch Nails. Gone were the nurturers who believed in a subtler kind of talent; it was no longer just about hits, but blockbusters.

The writing on the wall was foreboding, but Griffin wasn’t ready to let go. To understand her determination is to consider how she grew up: the youngest of seven in a small town in Maine, next to an Indian reservation, hers was a world of hard work, small dreams, and no sense of how great it was going to be. As a young adult, she’d left home for Florida, dreaming of seeing a different kind of life, playing the guitar she’d bought for $50 at 16 and figuring out how to be a songwriter. To support herself on her largely self-fueled path to finding her art, she eked out a living waiting tables. And never gave up.

But years later, tasked with delivering the third album that was supposed to be her proverbial big one, she wasn’t sure she could give the new powers that be what they said they needed. “Having been a waitress, waiting on people ‘til I was 30, 31, I was really just trying to finish my job,” she laments, half-ruefully, half-laughing about it now. “I was covering songs, turning in tracks … but it didn’t matter.

“By the time we finished working on it, I was so burned out,” she laments. “The record company I was signed to? It was gone. The new company had no interest in me. Artist Development wasn’t something they were doing …

“They didn’t get it.”

The resignation of a woman raised with just enough tempers her story. But her lingering sadness about the situation is still almost palpable.

“I was 37 years old when I had that meeting with Jimmy Iovine, and all I was asking for was a second chance,” she explains. “When I asked, it felt like there was almost a collective smirk in the room. (It was) Jimmy Iovine and four other guys, one of whom was actually checking his watch.”

Iovine informed her she’d never made a great record. Gave her a copy of the latest U2 extravaganza. But Patty Griffin records aren’t about grand gestures, massive arrangements, and broad, sweeping hooks; they’re redolent with vulnerability, inner strength, and wisdom. Or as she says, “I’m half Irish, half French-Canadian. I’m heavy on the emotions — and I don’t think in these times it’s palatable to the general public.”

And that was that. Griffin was dropped from the roster, and the anticipated Silver Bell — a handful of advance promotional copies of which had already started filtering out to tastemakers and critics — was unceremoniously yanked from the label’s release calendar.

“We knew almost before it was done that it wasn’t gonna come out,” says Joyce, who produced half of Silver Bell. “(Iovine) didn’t know anything about her. She was just one of those artists that was gonna be in the room that day. It was degrading to her.”

“To me, the whole story is about what you think having a life with a recording career is all about,” offers Griffin. “Then overnight, you wake up, and it’s over. When I was getting shoved out, they had some great artists — but it made me feel not good enough, which wasn’t true. I just wasn’t ‘on trend,’ and the old label situation was never about that. But when the takeover happened, and I was with that bunch of strangers, I was in such a hurry to not work minimum wage again, I’d rushed out to do whatever I could … and it wasn’t enough.

“I didn’t realize it would effect how I felt about myself as a musician,” she continues. “I walked away not knowing that. But I felt like something died, like I saw the end of a dream, you know? You held those albums in your hands as a kid, and you watch the labels go around and around and around — Columbia, SwanSong … It felt like all that was over.”

But not her music. Her confidence may have taken a crushing blow, but Griffin gathered herself and reckoned it out. As she admits with a slightly morbid laugh, “I’ve always known I could go out into the street and busk.

“I don’t know if it’s from growing up poor, but I chose to be a musician,” she confesses. “I could’ve gone to college, got into hock up to my eyeballs, but instead I went straight to work. That gave me a heat, an under-my-butt fire to pursue this and make it. When you do that, you can find the things you need when you need them.”

* * *

Let’s take a side trip. To bucolic Delray Beach, Fla., a small seaside town on the Atlantic, populated by demi-moneyed Midwestern snowbirds seeking warmer weather to ease their aging joints. It’s where Griffin went when she left home in search of a sense of self and self-reliance, removed from the harshness of the New England climate and the needs of her extended Catholic family.

“I didn’t have a plan,” she admits. “I just wanted to have a good time. I was a kid, the youngest of seven. I had discipline, but didn’t have any sense of independence. So I left with a couple hundred dollars in my pocket and a friend who was my roommate.”

She found warmer weather and just enough work pulling early morning waitress shifts to get by. It wasn’t necessarily easy making ends meet, but she looks back on the struggle in a positive light.

“We had to get our shit together,” she says, laughing. “But it was great for me: I had to make a living … and instead of having that party life I’d heard about, I got to see a lot of people doing drugs. Where I was working, there was so much cocaine going on, I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want to do that.’ It just didn’t look good, the way people were on it. So, I escaped trouble there! I didn’t have a car, so I rode my bike everywhere. It was just this really different kind of life down there. I hardly had to wear clothes. It was almost the most feral I think I’ve been in a certain way, but really balanced, too, because it was so simple.”

Between listening to reggae at iconic local bar Boston’s and dancing away nights to the urban/Latin sounds of the area, Griffin realized music in Florida was plentiful. But not the kind she wanted to make. The balmy life in mid-Palm Beach County was simple, but this was not the land of her dreams.

As the bus gently idles and Bean dozes on, Griffin considers those days of innocence and independence. “There was just no future beyond that,” she says. “Maybe meet somebody on the beach on Saturday, and you’d get married the next year — that was the future of that situation, the only thing I could see happening.”

Eyes brightening like coals you blow on, she leans forward to the seeming challenge. “But I think you kind of roll into things,” she says. “You have to follow your desires. You just keep staying open to whatever it takes to get that desire to be alive and working for you. (Some people plan), but I never thought of my life that way. I’m always right where I’m at, (taking) what that can bring me.

She pauses, looks up over the coffee steaming before her, and smiles. “I think (being that way) confuses people. But left to my own devices, I don’t really worry about the future.”

She may not worry about the future, but she’s never been one content to fully settle, either. Years later, she’d draw on that instinct to find her footing again after Interscope kicked her to the curb. Back in Florida, it steered her away from the path of least resistance and kept her dream in focus.

“I knew I wanted to sing,” she says. “In my younger years, it was a matter of A) convincing myself it was okay to do it, then B) learning how to do it well.”

Her years in Florida were ultimately key to shaping the artist she would grow into. What she took from those carefree days of being young, soaking up the sun and drinking cheap beer with the other expats seeking escape from the snow, their lives, or loves they couldn’t face, was an outsized appreciation of how life hollows you out inside, the sad notion of what’s lost, the emptiness of aging, and the need to find recognition, if not connection, in others. Those themes, as well as that place, have been echoed time and again throughout her work, from Silver Bell’s “Perfect White Girls” and “Mother of God” to Impossible Dream’s “Florida” to American Kid’s “Don’t Let Me Die in Florida.”

There’s a headiness to the freedom of independence that often recedes to leave one reckoning with the vastness of life. It is in the knowing that that the real adventure begins. For Griffin, that adventure would lead her back to the Northeast, where she continued to learn the craft of the singer-songwriter in earnest playing coffee house gigs. She kept singing, waiting tables and waiting on her dream, and eventually a demo tape led to a record deal. Ironically, A&M hated the record Daniel Lanois’ protégé Malcolm Burn made on her, but loved the startling emotional nakedness of the demos that came before it. And so Living With Ghosts was born.

* * *

After losing her record deal, Griffin figured there was only one viable option for her: get up, and get going. No matter what, no matter how.

“Right when it ended, I ran into (music writer) Dave Marsh at South By Southwest, who told me I’d just been ‘freed up,’” she recalls. She wasn’t quite that optimistic about the circumstances, but ever the pragmatist, she knew she had to keep her head up — “To get back in there, get back out there.”

Getting back in and out meant doing “a ton” of preproduction with guitarist/ producer Doug Lancio, who had a 16-track digital studio at his home in Nashville. Together they made 1000 Kisses, a folkie-bottomed record where the claret and chianti tones in Griffin’s voice captured the glimmers of warmth and shadows of doubt equally. Whether it was the dubious faith in connection of “Tomorrow Night,” the lambasting recounting of the displaced vet “Chief,” or the accordion-bathed wheeze of every day “Making Pies,” her voice defined the record. Her rendition of Bruce Springsteen’s “Stolen Car” had the dying-inside agony of falling apart, stoic yet consumed with disappointment. But her forceful strumming on “Long Ride Home” seemed to square her drive to stay alive.

Unlike its waylaid and orphaned predecessor Silver Bell, 1000 Kisses was not long in finding a home. Neither was Griffin. Dave Matthews’ recently launched ATO Records welcomed the respected singer-songwriter onto its early roster and released 1000 Kisses to wide critical acclaim in early 2002. Griffin would remain with ATO through three more releases: 2003’s live A Kiss in Time, 2004’s Impossible Dream, and 2007’s Children Running Through.

Impossible Dream, produced by Austin’s Craig Ross, showcased a more taunting, more kinetic Griffin on the mic. Buoyed by a renewed sense of confidence and the encouraging support of guests Emmylou Harris and Buddy Miller, songs like “Love Throw a Line” saw a woman in full emerging, equal parts survivor and fighter. And she could still float a wallop of a hard truth on an angel’s kiss. “There’s a million sad stories on the side of the road/We just got used to the blood,” she sings on “Cold as It Gets” with a brittle voice, straight from the Appalachian holler. “There are a million sad stories that will never get told.”

If she’d been seeking, she’d found something in Ross’ studio that nurtured whatever was broken inside. Mavis Staples, the gospel singer, was floating through the air. If she’d been lost or battered by the business, there was a place she could go in that brimstone and forged-earthenware voice that sustained her.

“I walked into Craig Ross’ house, into his studio, and said, ‘Who’s that?’ He said, ‘The Staple Singers.’ It was exactly what I needed to hear: their old gospel stuff.”

Cradling her coffee cup, Griffin smiles to herself. Mavis Staples took the doubtful daughter of Catholics to church in a way she’d never considered. It stuck.

“I’m not a Jesus person,” she concedes. “I’m not exclusively into any religion. But music is probably my religion, and she has a direct connection to whatever that source is, which nobody can ever really agree on because it is so mysterious. She’s connected to it!

“I met Mavis. When I first talked to her, I said, ‘You sang this song, and I’m trying to remember what it was …’ And she said, ‘Was it “The Weight”?’ ’Cause she figured I’d heard the Band do it …”

Hilarious laughing interrupts her explanation about divinity and modern music. She can see the humor in the obvious double down, but she also finds the irony in how far that was from her reasons for believing. Picking up the thread, Griffin continues, “I was like ‘No, it was one of your gospel songs.’ Because that gospel music got me through. Listen to ‘Freedom Highway.’ First of all, the lyrics are profound, and umm, it just kicks your ass into being a better a person, into lightening up and finding the joyousness.

“I just had a gig with her a couple nights ago, and she’s still connected to it,” Griffin marvels. “She still has, not quite the same range, but she still goes right into it: straight through you. It transports you to a much higher place; it’s a direct hit. I can’t imagine even pretending it’s something else… (What she does) is so beautiful.”

Impossible Dream rippled with the same sense of transcendence and transition. She’d grown clear enough to feel her own powers, to engage in “Top of the World”’s speculation, the enduring “When It Don’t Come Easy,” even isolation’s deafening presence in “Icicles.”

She didn’t know, but she didn’t worry. Somehow it would all turn out. Having had all the big promises go bust, music remained.

As strong as Griffin sounded on Impossible Dream, her next album was even bolder. Aiming to rock a little harder, to be a little more upfront and aggressive with her production, she enlisted Mike McCarthy (Spoon, … And You Will Know Us By the Trail of Dead) for the recording of 2007’s Children Running Through. The album opened with a coy whisper: the laconic “You’ll Remember” was torchy, spare, and all about Griffin’s vocal tremble. But it ceded to the funky, horn-drenched swagger of “Stay On the Ride,” and before it was all over her temerity was front and center. Though the sonics weren’t quite up there with the full-on, no-brakes intensity of Flaming Red, the ravishing beauty of songs like “Trapeze,” “Burgundy Shoes,” and “Heavenly Day” (celebrating the life of her dog) — not to mention the steely, mantra-like conviction of “I Don’t Ever Give Up” — was every bit as formidable.

Perhaps most powerful of all, though, was the Children track that would prove to be a telling glimpse of Griffin’s next artistic turn down the road. Listen to the hymn-like majesty of her voice on “Up to the Mountain (MLK Song),” swelling to the rafters above the bed of upright church piano, and you can hear the unfurled gospel spirit of Mavis Staples moving through her.

* * *

Griffin’s six-year, four-album run with ATO was a bountiful one, cementing her standing as one of America’s most respected singer-songwriters of recent vintage. But Children Running Through, which netted a Grammy nomination for Best Contemporary Folk/Americana Album, was her last with the label. It was also her last album of all-original material for five years. Griffin’s reflections on the death of her father in 2009 would deeply inform her American Kid album four years later, but at the time of his passing, she just wasn’t ready to put her grief into writing, much less commit it to tape.

Instead, she turned to the Lord — conceptually, at least.

“To me, Downtown Church came out of loving the Staple Singers,” Griffin explains. “Listening to them, I’ll bet, every day for five or six years: every day. Almost like OCD. Because singing (their songs) just feels good. And you’re singing, trying to pick up all those parts because they’re a family, so you can’t always tell the voices and the parts! It’s just one voice sometimes: the Staple Singers.”

Almost cosmically, the offer to record a gospel record for a small independent label (Nashville’s Credential Recordings) came at a time when Griffin really needed it. “I think having a gospel record to do when my father died, and I felt pretty vulnerable, was a great thing to have,” she says. “I just wanted to use my voice and not think about writing lyrics for a few minutes. I did end up writing a few things, but (Downtown Church) goes back to that singing thing: What is it? Because singing’s a weird thing to do. I don’t think it’s so far off from … speaking in tongues.”

To help her capture that mystery on record, she turned to longtime friend (and avowed Griffin fan) Buddy Miller. Although the two had known and worked together for years, both on the road and in the studio, it was Miller’s first time producing her. He came to the project with the perfect studio in mind: Nashville’s Downtown Presbyterian Church.

“She wanted to be in a room where she could hear her voice coming back at her,” says Miller. “I’d just done a show there, so I figured I could ask, and they couldn’t have been easier. ‘We’re Protestant, so we’re done after Sunday service,’ they told me. We loaded in Sunday afternoon and loaded out Saturday night. Maple Byrne (Emmylou Harris’ longtime guitar tech) slept in the church every night to make sure the gear was safe. I put her in the pulpit singing, then set us up in a semi-circle, looking up at her like she was giving some sort of sermon.”

The results, par for both artists’ track records, were stunning. But beautiful though the tracks were, Downtown Church was so different from any album Griffin had ever made before that a warm embrace by the public was by no means a given. Not only were the fans — who loved her writing — getting an album comprised almost entirely of traditional songs and covers (save for the two Griffin originals, “Little Fire” and “Coming Home to Me”), the record was unabashedly spiritual. Outside of Leiber & Stoller’s “I Smell a Rat,” every song touched on faith and salvation.

“I knew it would be an uncool thing to do,” Griffin acknowledges. “I knew the perception would be difficult for a lot of the fans, because there was such an animosity between people who feel they have a grievance with that super right-wing kind of, even unhealthy, hate-mongering excuse for religion. It’s so prominent, and was prominent when this came up. There’s just a lot of crap, and it’s a big business, and there a lot of people — friends of mine, and I consider myself a part of this group, too — who feel they have a grievance with what Christianity has become. But, since I also know lots of people who are Christians who are good people, including my parents, I felt I owed it to myself to go into this without prejudice. I mean, I love Mavis, and she’s a Christian.”

Griffin pauses, considering the polemics: alienated Catholic girl loses her father and is offered the chance to do an album filled with songs of faith. Turned off to the business of religion, it was an opportunity to tap into the root of salvation.

“How do you put the two together?” she asks. “How do you face your fear about it, and make the goal line about this music and sing it like your own? This is all a personal exploration, this music business and this music. It was an opportunity. It seemed like all the pieces were in place, to make it at least enjoyable. So that was a reason …”

There was also the reassuring presence of Miller, who’d known her since almost before there were Patty Griffin records. And so ultimately, like the protagonist in all great stories of faith and deliverance, Griffin did the obvious: she surrendered to it. Not always easily or completely at the outset, but with humor. She recalls her attempts to adapt and “tweak” some of the lyrics, “so I could get through them with my own interpretation” — and Miller, a Christian, having to put his foot down.

“We got to the Saint Francis of Assisi one (“All Creatures of Our God and King”), and I was like, ‘What if we just …’ and Buddy’s like, ‘Uhm, yeah, Patty … that’s Saint Francis’ text. We can’t change that!’”

Griffin laughs; not quite nervously, but with a hint of self-deprecation. She pushes the hair off her face, rolls her eyes a bit acknowledging her discomfort about it all. Then she drops her truth like a gate.

“For me, as a Catholic, one of the most damaging things was the patriarchal, all-knowing symbolism,” she says. “It kind of leaves the females devastated in the area of self-empowerment. There’s been a lot of choices in how to teach Catholicism that have really screwed women, so I’ve had a hard time with all the patriarchal stuff.”

Faith means walking through fire without knowing how. It means trusting something other than oneself. It means believing in the end when you can hardly see the beginning. Sometimes it means releasing what you “know,” the pain and differences of experience, in the name of what you’re seeking.

“As I was singing the song with John Deaderick playing the piano so beautifully, I started to see what St Francis of Assisi might have seen when he wrote it,” she explains. “And it all went away. I just went, ‘Okay. That’s what this is all about …’ They’re just words, but words that say something that’s coming out of your heart. That’s what (this) singing’s about: words are secondary to that.”

* * *

Through the experience of making Downtown Church, Griffin found something in her grief that had been there all along. It was a different kind of faith, a different kind of revelation and fire. She was always one of the most compassionate songwriters, pushing back the obvious and the bias to show the wounded children, lost souls, and damaged grown-ups below the less-than-perfect exteriors. But now there was a temporal glow, too. That shine only got brighter as Griffin took her grieving time and joined forces with Band of Joy, seeking refuge in moving out of the spotlight and finding definition in the process of building music with a band of fellow seekers.

“I just wanted her voice to be on the record — and who wouldn’t wanna sing on that?” says Miller, who landed the gig producing Robert Plant’s follow-up to Raising Sand, the legendary Led Zeppelin frontman’s “Album of the Year” Grammy winning collaboration with Alison Krauss and producer T Bone Burnett. Miller had been featured on Raising Sand’s tour, leading to his from-the-ground-up involvement in the all-star Band of Joy and the album of the same name.

“Her voice just has the coolest texture to it: this airy quality that can go places, yet also get so guttural and can rock!” he continues. “She can do it all, and doing that gospel record really proved that. So, I asked. And it was a little bit of figuring it out, cause we didn’t know how long (Band of Joy) was going to go, or what would happen …”

Griffin didn’t, either. But she was game. “To go straight into back-up singing after Downtown Church was pretty awesome,” she enthuses. “Because that is vulnerable, and it doesn’t always fall within your strength capacity to do that. I know that Robert would be upset with me (for saying that), but I always wanted to be a back-up singer! It takes so much to do that.”

Griffin may not have been the name on the tickets, but her presence added a definite depth to the blues/folk/mystic rock that Plant, Miller, Darrell Scott, Marco Giovino, and Byron House were making. In true hippie style, Band of Joy remained a work in progress throughout its tenure — and it rippled into Griffin’s sense of what comes next.

Band of Joy ended up touring the world, accompanied by blues-minimalists the North Mississippi Allstars as the support act. There was a family vibe shared amongst all from very early on, with Plant — not booking agents — personally extending the offer to Allstars brothers Cody and Luther Dickinson to continue with the tour. And when Griffin started thinking about her next record, she called Cody herself.

“She left me a message, saying she was interested in making a record and was wondering where should we record,” Cody remembers. “I said, ‘Come to Mississippi, please! Come to our Mom’s property, to our barn, which is the Zebra Ranch. It’s where we grew up, so there’s a sense of family and togetherness and a world-class studio.’”

He pauses, then offers context for those who don’t realize he’s the son of legendary producer Jim Dickinson. “It’s an incredible place to be an artist: all that history and tradition and the legacy of my father. There’s the enigmatic nature and emergence of the blues in North Mississippi and the richness of all that’s here.”

Griffin agreed. She knew she wanted a stripped-down record. She knew she had songs to sing, and Craig Ross in tow as a producer. It was just a matter of making it work. And for the Dickinson boys, making sure the place was ready for their musical crush.

“So Patty brought Robert and everybody to our family studio, which is an old ramshackle barn,” Luther explains. “All I could think is, ‘We gotta clean this place up!’ We hired a dumpster and filled it to the top. And we had this beautiful antique throne for her to be sitting on. But that wasn’t it …”

Like a shy kid, Luther, the string-wizard brother, drops his voice and explains the magic. “This is the only studio in the world with wind. You can hear the sound of the wind blowing through. We had all the doors and windows open, and it was just part of it.”

While Griffin’s musical wanderlust and desire to explore new places is a piece of what makes her fascinating to watch, it’s not a matter of Madonna-like reinvention. Her fearlessness as a writer, scraping the paint to see what’s beneath the layers, is endemic to all facets of her artistry.

“It was so bold,” Luther continues. “She’s just won a Grammy for a gospel record recorded in a church. Then she wanted something as straightforward and from the heart, as unadorned, as possible. So she was determined to follow it up in a barn in Mississippi: organic by design, and ‘get live vocals!’ In this day, nothing’s organic. But this? This is the summation of her whole life experience. She didn’t know what she was getting involved with, but she knew what she wanted, and I think it’s mournful because it’s one of those records that looks right in the eyes of mortality. It’s very blue, in a way …”

Indeed, American Kid is a sobering look at life. But it’s also a record about the redemptive qualities of letting go: of worries, expectations, and yes, life itself. Things that are hard, even daunting, just are. And Patty Griffin, still very much the wickedly youthful songstress as she approaches 50, is finding peace and grace and joy. It gives her a perspective with which to embrace it all.

“My Dad was old, but I didn’t know he was gonna pass away,” she says of the album’s grounding inspiration. “I couldn’t have put this (album) out when I first wrote this stuff, so I got busy with the gospel record, then Robert’s stuff. I couldn’t have made this record: there was too much to put out there when it was all so fresh …”

She pauses. It still hits her in the heart, as all close deaths do. But legacy and reality have a way of easing through the cracks, pushing apart plates of resistance, letting the light find the darkest places.

“Probably the first song was ‘Not A Bad Man,’ and it’s about a veteran coming back,” she says. “That last decade we were in was so about the war, and the greed — and the discovery of that, especially that. And then here was this kid who’d come back from the war, only to be thrown away because he was so traumatized … and that alienation only grew deeper.”

Griffin wasn’t looking to preach, only to gently point people to awareness. Political, yes, but personal, too. The songs on American Kid tell stories of her grandparents’ courtship and wedding night (the quiet “Irish Boy,” the randy “Get Ready Marie”), and marital tenderness (“Mom & Dad’s Waltz”). There are also glimmers of raging against age with a zest for life (the churlish churn of “Don’t Let Me Die in Florida”), the emotional bankruptcy that comes from the diligence of measuring up to expectation (“Faithful Son”), and the joy of mortal release and acceptance (the gently striding album opener, “Wherever You Wanna Go,” and the hushed torch closer, “Gonna Miss You When You’re Gone”). The sum total is a full-spectrum look at life on life’s terms.

“‘Dead strings and ribbon mics’ — Buddy and I joked — ‘that’s how you make folk records,’” offers Luther. “But Patty was just blowing our minds and breaking our hearts, just learning these songs, and those lyrics. She’s just so open and willing and honest; she’s got the touch. I mean, a grown woman looking at her grandparents on their wedding day? It’s the cycle of life.”

“She’s brave enough to be vulnerable,” seconds Cody, “to engage us all, to bring us into her world. I’d watch her mouth, literally, as I played. I’d watch her lips, her body language, the way she moved to get out of the way of her vocal. That’s the blues tradition, which is as old as it gets.”

Cody pauses, trying to explain the stakes. “In a way, I’m afraid of them all: knowing how special the songs all are, and the delivery. I want to break my heart and soul to every beat.”

That’s the devotion Patty Griffin inspires. But even with that, she keeps her head down, refusing to be swirled in the trappings. As Luther says of her time in Mississippi, “She wanted a beige hotel, a very suburban, American interstate hotel, and Robert would drive her to the studio, then drive around all day while we worked.”

Robert Plant’s name alone is larger than most myths. Respectful of her autonomy and aware of the power of her writing, he is careful to maintain a distance to not allow his shadow to fall on her. But Plant, a music man of deep roots, is present on the haunting “Ohio,” a song of slaves meeting or lovers rejoining after time apart; weightlessly, their voices circle and twine, rising on the wordless “uhhhhhh…” with a celestial glow.

“It was just amazing to watch Robert and Patty together,” Cody says, awestruck by their intimacy and passion. “They give me hope. He’s such a gentleman, and they’re so in love. To watch it all go down on the Band of Joy tour, to see that, and to see the way it’s grown …”

You’re not told by management and handlers to not ask about Griffin’s paramour, but it’s obvious there is little about their relationship she’s going to discuss. He untangled the Gordian knot that was “Ohio,” rearranging and suggesting changes. Without saying anything, you know this is something sacred and powerful: she doesn’t need to Tweet about her significant other or make hyperbolic declarations for its impact to be recognized.

Besides, after all of it — the hardships and loss, the soldiering on, and the crummy deals at the hands of a music business that doesn’t fractionally value art as much as commerce — surely this woman, whose songs have inspired so many, is entitled to a little fairy tale to keep to herself and call her own.

And so.

* * *

Not dissimilarly to allowing the artist a little private space to call her own, one can also make a case that a Patty Griffin record as deeply personal, resplendent, and beautiful as American Kid was deserving of a year to call its own, too. It was not to be. In October 2013, just five months after American Kid’s release on New West Records, Universal Music Enterprises — the mega label enveloping both A&M and Interscope, among many other subsidiaries — saw fit to retrieve Silver Bell from the depths of its dead-record vault, blow the dust off, and give it a commercial release, replete with all the fanfare befitting a “long lost” masterpiece by one of America’s most esteemed songwriters.

A songwriter, not coincidentally, whose prestige and visibility of late just happens to be at an all-time high.

But all things considered, regardless of however opportunistic or questionable the timing may be, there is this to be said about the album’s release: better late than never.

Remixed by Glyn Johns, who Griffin met years ago while opening for Emmylou Harris in London, Silver Bell is in many ways a stranger to the woman who fought so hard for the songs almost a decade and a half ago.

“I’d not listened to it a lot over the years,” she concedes, knowing sometimes the best defense is to not mourn what can’t be. “When Glyn came in with the mixes … I was on the road, and I’d put on my headphones, and … it just amazed me to hear these songs, and how he’d uncovered them.”

Of course, Griffin had previously “uncovered” some of those old songs herself, recutting Silver Bell songs like “Top of the World” and “Mother of God” for later albums during her stint with ATO. And the original versions haven’t gone entirely unheard all these years, either. Copies (or copies of copies) of those initial Silver Bell promos disseminated prior to its shelving have been aggressively traded amongst the rabid faithful, swapped by fans, whispered about by musicos, and even mined for songs by other artists. Natalie Maines has joked that it’s her private stock. She recorded the song “Silver Bell” for her 2013 solo album, Mother, and her trio the Dixie Chicks recorded both “Truth #2” and “Top of the World” for their 2002 album, Home. Soon after, in the face of what seemed like an entire genre turning on them — especially noted “boot in the ass” kingpin Toby Keith — following an off-handed Maines comment about George W. Bush during a concert in London at the outset of the war in Iraq, the Chicks took “Truth #2” as a personal battle cry.

“I’m still dumb-founded by what happened to them,” Griffin marvels. “They were all, especially Natalie, targeted: the death threats, the hate … But (knowing) that song helped them stand a little taller in all that, it thrilled me. I love that that happened.

“It’s almost like the universe doing the work.”

The universe works in strange ways. For Griffin, the path has been rocky and faith-testing, but not without its rewards: some small, some grand, but every living moment a lesson and a gift. And captured in songs, written and sung, those personal life experiences and memories become something even more.

It it was never her mission to stun and captivate. She was just an American kid from a big family, looking to find her place playing music. She wanted to write as well as she could, sing with truth and all the beauty she could summon. She wasn’t afraid of not getting there; “there” was wherever she was. But she didn’t want to fall short of what she could do.

Jay Joyce, also from a large Catholic family from the poor part of an industrial city (Cleveland), understands. “I don’t think she thinks she’s as good as we do,” he says. “That Catholic guilt thing? We all do it, think we’re making too much of whatever it is. There aren’t enough Billboard magazines and awards to fill that up. It’s probably not healthy, but we’re making art here. And Patty’s very committed to the songs. That’s what matters, and if it matters, is it ever enough? We may think so, but those are her children.”

But like all true voices, Griffin’s songs speak to (and through) people where they are: From Dixie Chicks under fire to out of the mouths of babes.

“The meaning may move,” observes Luther Dickinson. “I wanna sing a country-blues version of ‘God is a Wild Old Dog.’ And my daughter, she’s not even 4, is singing along with it in her little baby voice. And my Mom and I were talking about the song the other night, and she’s feeling it, like, ‘God has a wild old dog.’ And what could be more beautiful than that?”

Nothing shy of Griffin’s own recollection of the bittersweet encounter that inspired the American Kid song in the first place.

“When I saw that dog, my first thought was, ‘What a beautiful dog …’,” she says. “There he was on the median, on a beautiful day, all alone, and it didn’t occur to me at first what was going on. And I watched him. He took off running. What else is he gonna do, except take a good run? He was gonna live it out, whatever the moment holds, really see what’s there.”

She pauses for a moment, weighing the memory, turning over the cruelty and the freedom in her mind.

“He didn’t think about what had happened. He was just gonna be in the moment: just go for it. In some ways, he didn’t worry. He was.”

Fantastic timeline of her career and Patti as an artist and person.