By Scott Schinder

(LSM Jan 2014/vol. 7 – issue 1)

If one were to invent the story of a tragic, tormented cult hero who failed to receive a level of fame and fortune commensurate with his achievements and influence, it would be hard to create one more dramatic or colorful than the saga of Austin-bred psychedelic trailblazer and horror-rock master Roger Kynard Erickson, better known to his friends and fans as Roky.

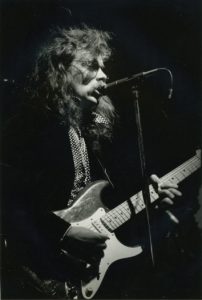

Roky Erickson is a genuine original, and a genuine eccentric, in a field in which those terms are thrown around too easily. As lead singer, rhythm guitarist and co-songwriter of the 13th Floor Elevators, Erickson helped to pioneer ’60s psychedelia, matching his wild-eyed banshee wail to the band’s acid poetry and expansive sonic excursions. In his subsequent solo career, he plumbed the depths of his tortured soul to create uniquely powerful rock ’n’ roll that mined horror-movie imagery to evoke the monsters that plagued his soul.

Along the way, unfortunately, Erickson has paid the same penalty extracted from many of those who’ve flown too close to the sun. He’s spent extended stretches of his life in personal and creative limbo, while his struggles with mental illness and drug abuse made him a legend for the wrong reasons.

The more tragic details of Erickson’s life often threaten to overshadow the power of his musical output. It doesn’t help that his discography is one of the most convoluted in rock ’n’ roll and has been a shambles at many points, with numerous marginal, disposable, shamelessly exploitative and/or legally questionable releases flooding the shelves while some of his greatest music has remained difficult to obtain for long periods. That situation has been redressed by the recent release of expanded versions of the Elevators’ original studio albums, along with the three solo albums that helped Roky to reach a new, punk-savvy audience in the ’80s. So now is as good a time as any to survey the ins and outs of his catalogue.

Assembling a library of essential Roky Erickson music is actually a fairly simple task, since his best work is contained on a handful of albums. Navigating his catalog’s more shadowy corners, where the listener must figure out the difference between the minor gems and the shameless ripoffs, is where things get more challenging and interesting.

In their turbulent 1965-1969 existence, the 13th Floor Elevators created a sound and sensibility that was utterly unlike anything heard before. Although the band’s ostensible raison d’etre was the oddly graceful acid-poetry lyrics by founder/leader/guru Tommy Hall, the band’s real genius was in its visionary sound. Guitarist Stacy Sutherland’s innovative use of reverb and echo sometimes made him sound like an extraterrestrial Dick Dale or a subterranean Dave Davies. Along with Erickson’s voice and Sutherland’s guitar, the Elevators’ other trademark was the otherworldly “electric jug” of Hall, who, lacking conventional instrumental skills, used an empty jug to create echoey, distorted vocal lines that hung ghostlike over the band’s music.

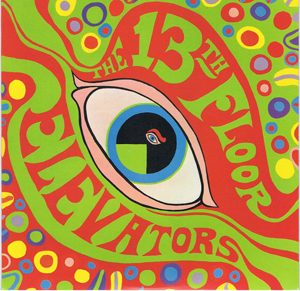

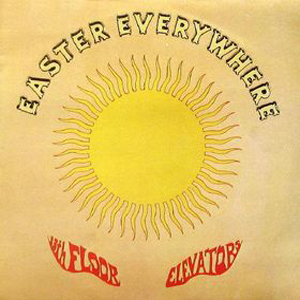

During their lifetime, the Elevators released three studio albums on the Houston-based International Artists label, which in the second half of the ’60s also became the home to such other oddball Texas psychedelic outfits as Bubble Puppy, the Red Crayola, and the Golden Dawn. The Elevators’ first two longplayers, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and Easter Everywhere (released, respectively, in 1966 and 1967), are essential classics that belong in the collection of anyone interested in psychedelia.

During their lifetime, the Elevators released three studio albums on the Houston-based International Artists label, which in the second half of the ’60s also became the home to such other oddball Texas psychedelic outfits as Bubble Puppy, the Red Crayola, and the Golden Dawn. The Elevators’ first two longplayers, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and Easter Everywhere (released, respectively, in 1966 and 1967), are essential classics that belong in the collection of anyone interested in psychedelia.

The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators, recorded when Roky was just 19, opens with the savage Erickson-penned garage anthem “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” which reached No. 55 on Billboard’s national pop chart (although it charted higher in many regional markets through the Southwestern U.S.). Although it remains the Elevators’ (and Roky’s) best-known and most-covered song, it’s not representative of the band or the album. For one thing, Erickson’s lyrics offer snotty teen garage petulance in place of Hall’s lysergic mysticism. (Erickson had previously released a slightly less frantic version of “You’re Gonna Miss Me” as a 1965 single with his previous band, the Spades, and brought the song with him when he joined the Elevators).

Beyond that savage opening, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators is a consistently riveting listen even without chemical enhancement, with such Erickson co-compositions as “Reverberation,” “Roller Coaster,” and “Fire Engine” embodying the band’s uplifting-yet-uneasy sound. Elsewhere, the haunting “Splash 1,” which Erickson wrote and sings with Tommy Hall’s wife Clementine, showcases the tender side that would remain a recurring presence in Roky’s work.

The Elevators’ 1967 sophomore effort, Easter Everywhere, is a tad less tense and edgy, but more accomplished and consistent. Recorded mostly with a new rhythm section, it’s loaded top-to-bottom with memorable material, including the epic Erickson/Hall collaborations “Slip Inside this House,” “She Lives (In a Time of Her Own),” “Earthquake,” and “Dust.” Those tunes rank with the band’s greatest, as does “I Had to Tell You,” another heart-tugging Erickson/Clementine Hall ballad, along with a cover of Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” that Dylan reportedly described as his favorite.

The Elevators’ 1967 sophomore effort, Easter Everywhere, is a tad less tense and edgy, but more accomplished and consistent. Recorded mostly with a new rhythm section, it’s loaded top-to-bottom with memorable material, including the epic Erickson/Hall collaborations “Slip Inside this House,” “She Lives (In a Time of Her Own),” “Earthquake,” and “Dust.” Those tunes rank with the band’s greatest, as does “I Had to Tell You,” another heart-tugging Erickson/Clementine Hall ballad, along with a cover of Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” that Dylan reportedly described as his favorite.

The Elevators began work on a third studio album, reportedly under the working titles A Love That’s Sound and Beauty and the Beast, in 1968. But the band’s increasing drug-fueled instability sidelined the project. Instead, International Artists slapped together Live (1968), a fake concert LP comprised mainly of demos and studio outtakes overdubbed with unconvincing crowd noise and assembled without the band’s participation. Although the result is of some minor interest for the inclusion of Elevatorized covers of Bo Diddley, Buddy Holly, and Solomon Burke tunes, it’s largely written off by the group’s admirers, with good reason.

Listeners wishing to get a true taste of the Elevators’ fabled power as a live unit will have to make do with the small handful of vintage concert recordings that have surfaced over the years. The best of these, in terms of sonic fidelity and performance quality, is an early 1967 Houston Music Theatre set that was first released by Big Beat in 1988 as Live: Rockius of Levitatum, and which has been sloppily repackaged multiple times, e.g. Magic of the Pyramids (on Collectables, a label that’s issued a number of dodgy Elevators titles) and Levitation. Also worth hearing in a September 1966 recording from San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom that’s available in various guises including Out of Order: Live at the Avalon Ballroom, Through the Rhythm and Another Dimension.

One live set to avoid is the one packaged as Last Concert and The Reunion Concert, which is actually a largely unlistenable audience recording of a 1984 gig from an ill-fated attempt by Erickson, bassist Ronnie Leatherman, and drummer John Ike Walton to revive the Elevators minus Sutherland or Hall. Although six of the eight songs are actually from Roky’s solo career, the show seems to have been a powerful one. But the miserable sound renders what should be a significant historical document fairly useless.

The Elevators — some of them, anyway — managed a final studio album with 1969’s Bull of the Woods. With Erickson and Hall only appearing on the four tracks salvaged from the unfinished A Love That’s Sound/Beauty and the Beast, it’s mostly Stacy Sutherland’s show. Bull of the Woods has some interesting moments, many of them offering an interesting mix of shadowy psychedelia and twangy rural rock. In terms of Roky content, though, it’s a footnote.

The 13th Floor Elevators’ albums remained out of print and difficult to find for many years, until CD reissues began appearing in the late ’80s. Since then, the band’s output has been revived by numerous labels in countless packages of varying quality. In 2009, Britain’s Charly label (which was the first to reissue the Elevators catalogue on CD, albeit with scattershot fidelity) released the limited-edition 10-CD box set Sign of the 3-Eyed Men, which collected the Elevators’ studio albums along with a hefty selection of rarities and live material. Although now out of print and nearly impossible to find at non-exorbitant prices, much of the box’s contents have been recycled in other recent packages. For instance, a set of early 1966 studio recordings that predate the recording of the Psychedelic Sounds album is out separately as Headstone: Contact Sessions, while a CD’s worth of alternate singles mixes have been collected as 7th Heaven: Music of the Spheres/The Complete Singles Collection.

Despite the proliferation of Elevators ephemera, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and Easter Everywhere are still pretty much all the Elevators that most listeners will need. Both are easily obtainable, although some versions are better than others. The two-CD expanded editions of the three studio albums that Charly released in 2010 are a sonic improvement upon the label’s earlier versions of those titles. Those packages present the first two albums in complementary mono and stereo mixes, while pairing Bull of the Woods with a reconstructed version of its unfinished ancestor, A Love That’s Sound.

The market is also glutted with countless redundant 13th Floor Elevators compilations, some assembled with care but most tossed together with little rhyme or reason. Many of these packages (which bear such cute titles as Reverberations, His Eye Is On the Pyramid and All Time Highs) simply reshuffle familiar album tracks, while others (like Manicure Your Mind, Psych-Out and Psychedelic Circus) dredge up vaguely interesting but inessential studio outtakes.

By the end of the ’60s, the 13th Floor Elevators had crumbled, the victims of their own chemical excesses as well as a campaign of police harassment directed against the band, whose open advocacy of controlled substances made them an inviting target for law-enforcement authorities. In 1969, Erickson was arrested in Austin for possession of a single joint — at the time, a felony that carried a possible 10-year prison sentence.

Pleading not guilty by reason of insanity to avoid prison, Erickson was committed to the Rusk State Hospital for the criminally insane, where he spent three nightmarish years amongst murderers and rapists, and received electroshock and Thorazine treatments. During his stay, he formed a band with some fellow inmates, wrote a book of mystical poetry entitled Openers, and composed numerous songs. Most of those compositions would go unrecorded until nearly four decades later, when they would provide the basis for a surprise comeback album (more on that later).

When he was finally released from Rusk, Erickson was a changed man, with many observers agreeing that treatments he received at Rusk exacerbated whatever psychological problems he may have had before entering.

After a brief Elevators reunion attempt that resulted in a handful of live shows, Erickson formed a new band, Bleib Alien, later known as Roky Erickson and the Aliens. The band’s hard-rocking sound contrasted the Elevators’ otherworldly rumble, but complemented Roky’s feral howl and new songs, which were both raw and melodic. His lyrical references to horror movies and supernatural phenomena turned the demons, zombies and vampires that populated his psyche into unmistakably personal music and engaging, asymmetrical wordplay.

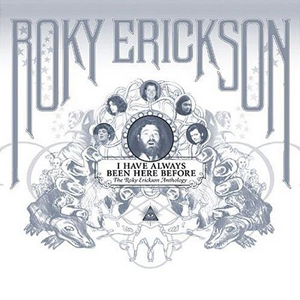

Erickson returned to the studio with longtime admirer and fellow Texas iconoclast Doug Sahm, who financed and produced two songs — the harrowing “Red Temple Prayer (Two Headed Dog)” and the yearning, Buddy Holly-esque “Starry Eyes” — and released them as a single on the short-lived Mars label in 1975. “Bermuda” b/w “The Interpreter” followed in 1977, released by Rhino in the U.S. and Virgin in the U.K. The same year, the French Sponge label released an EP containing “Red Temple Prayer,” “Mine Mine Mind,” “I Have Always Been Here Before” and “Click Your Fingers Applauding the Play.” Erickson would rerecord these essential numbers, in more professional, less frantic form, for subsequent, better-distributed releases, but the quirkier original editions are collected on 2005’s I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology.

Erickson returned to the studio with longtime admirer and fellow Texas iconoclast Doug Sahm, who financed and produced two songs — the harrowing “Red Temple Prayer (Two Headed Dog)” and the yearning, Buddy Holly-esque “Starry Eyes” — and released them as a single on the short-lived Mars label in 1975. “Bermuda” b/w “The Interpreter” followed in 1977, released by Rhino in the U.S. and Virgin in the U.K. The same year, the French Sponge label released an EP containing “Red Temple Prayer,” “Mine Mine Mind,” “I Have Always Been Here Before” and “Click Your Fingers Applauding the Play.” Erickson would rerecord these essential numbers, in more professional, less frantic form, for subsequent, better-distributed releases, but the quirkier original editions are collected on 2005’s I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology.

In 1979, Roky and the Aliens recorded 15 tracks in San Francisco with Creedence Clearwater Revival member Stu Cook producing. Those sessions would produce some of the most lucid music of Erickson’s checkered career, encompassing many of the songs that would comprise the core of his repertoire for years to come, e.g. “Creature with the Atom Brain,” “Night of the Vampire,” and “Bloody Hammer,” which possess unusual, indelible hooks and oddly poetic turns of phrase.

To many ears, it’s the Cook tracks that offer the clearest entry into Roky’s raging musical soul, due to the energy of their performances and the clarity of the production and arrangements, although some devotees consider them to be overly polite, preferring the more unhinged earlier versions released elsewhere.

The Cook-produced material was originally spread over two overlapping albums: Roky Erickson and the Aliens, informally known as “Runes” or “Five Symbols” for its untranslatable cover characters, released by CBS in the U.K. in 1980; and The Evil One, released in America by 415 the following year. All 15 songs would eventually be collected on later CD reissues, which usually used the cover from the original British release and the title of the U.S. version. The best of these include Sympathy for the Record Industry’s 2002 double-disc The Evil One (Plus One), which adds a 1979 radio interview, with Roky previewing rough mixes from the album and offering a rare insight into his one-of-a-kind mind; and Light in the Attic’s handsomely packaged, smartly-annotated new issue of The Evil One (2013).

The Cook-produced material was originally spread over two overlapping albums: Roky Erickson and the Aliens, informally known as “Runes” or “Five Symbols” for its untranslatable cover characters, released by CBS in the U.K. in 1980; and The Evil One, released in America by 415 the following year. All 15 songs would eventually be collected on later CD reissues, which usually used the cover from the original British release and the title of the U.S. version. The best of these include Sympathy for the Record Industry’s 2002 double-disc The Evil One (Plus One), which adds a 1979 radio interview, with Roky previewing rough mixes from the album and offering a rare insight into his one-of-a-kind mind; and Light in the Attic’s handsomely packaged, smartly-annotated new issue of The Evil One (2013).

Recorded with three ex-Aliens and Jefferson Airplane/Hot Tuna bassist Jack Casady, the raw, rocking Don’t Slander Me — mostly recorded in 1981-1982 but not released until 1986 — is a little less focused than its predecessor. But its typically Rokyesque mix of love songs (“Nothing in Return,” “Starry Eyes”) and demonic exorcisms (“Burn the Flames,” “The Damn Thing”) makes it a consistent winner.  1986 also saw the release of Gremlins Have Pictures, which, despite being a collection of disparate tracks recorded in various places and with various bands through the ’70s and ’80s, is a consistently riveting listen, offering a heaping helping of Erickson’s talent and vision, and featuring some of his strongest lesser-known compositions. (Both Don’t Slander Me and Gremlins Have Pictures were also given superb reissues in 2013 by Light in the Attic.)

1986 also saw the release of Gremlins Have Pictures, which, despite being a collection of disparate tracks recorded in various places and with various bands through the ’70s and ’80s, is a consistently riveting listen, offering a heaping helping of Erickson’s talent and vision, and featuring some of his strongest lesser-known compositions. (Both Don’t Slander Me and Gremlins Have Pictures were also given superb reissues in 2013 by Light in the Attic.)

After the sessions for Don’t Slander Me but prior to its release, Erickson rerecorded three of the album’s songs (“Haunt,” “Starry Eyes,” and “Don’t Slander Me”) — along with the bittersweet folk rockers “You Don’t Love Me Yet” and “Clear Night for Love” — for 1985’s five-song Clear Night for Love EP. Those tracks would prove to be his last recordings for a decade, as he retreated from music and fell into life on the margins of society.

Considering the precarious state of Erickson’s mental health, it’s not surprising that he signed a multitude of bad contracts that resulted in all manner of dodgy releases, encompassing live recordings, demos, alternate versions and various other ephemera. Apparently he had no input into most of these titles, received little or no payment in most cases, and was not even aware of the existence of many of them. Some of these are blatantly exploitive and/or barely listenable, while others yield valuable insights. In any event, these releases helped to keep fans occupied during a decade-long stretch in which Erickson fell upon hard times and withdrew from musical activity. Among the more notable are Mad Dog and Love to See You Bleed, both on the mysterious Swordfish label. Mad Dog is an excellent collection of late-’70s demos and live tracks, including killer alternate versions of various Evil One and Don’t Slander Me numbers, many of which rival the official versions intensity-wise. Love to See You Bleed draws from the same pool of material, with less worthwhile music but more bizarre archival curios.

Of the numerous live discs, recorded with an array of backup bands in the late ’70s and early ’80s, Live Dallas 1979 and Casting the Runes feature good sound and incendiary performances. Beauty and the Beast includes a couple of hard-to-find songs, while Roky Erickson and Evil Hook Wildlife E.T. combines some savage mid-80s live numbers with a pair of incendiary studio tracks and brief interview snippets. The best of the lot may be Live at the Ritz 1987, which, despite its bootleggy recording quality, boasts a ferocious performance as well as an absolutely incredible 16-minute radio interview bonus track that’s worth the price of admission on its own.

1987’s The Holiday Inn Tapes is a casual lo-fi acoustic session cut at the title motel in Austin. Its contents, along with those of Clear Night for Love and the 1977 Sponge EP, are collected on the 1988 CD Click Your Fingers Applauding the Play. 1995’s Demon Angel: A Day and a Night with Roky Erickson contains few rare songs, but is generally a better listen, presenting the audio of a live solo set originally shot for a Texas TV documentary. 2004’s Don’t Knock the Rok! is possibly the oddest of oddities: a loose 1978 practice session with the Aliens consisting mostly of Roky’s stream-of-consciousness assortment of pre-Beatles pop and rock ’n’ roll covers.

Word of Erickson’s difficulties reached old friend and Warner Bros. Records exec Bill Bentley, who responded by assembling the 1990 tribute/benefit album Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye: A Tribute to Roky Erickson, which features a wide array of memorable interpretations by the artist’s contemporaries (ZZ Top, Doug Sahm) and acolytes (R.E.M., Julian Cope, the Jesus and Mary Chain). Unlike many of the all-star tribute albums that would follow, Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye succeeded as a musical statement, while achieving its goal of exposing Erickson’s material to a new generation of listeners.

The tribute disc also set the stage for All That May Do My Rhyme, released in 1995 on Butthole Surfers drummer King Coffey’s Trance Syndicate label. Promoted as Roky’s first new album in a decade, it actually combined five charming new, demon-free tunes, plus a duet reworking of “Starry Eyes” featuring Lou Ann Barton, with the contents of the 1985 Clear Night for Love EP. The result is surprisingly cohesive, showing Erickson to still be capable of crafting fetchingly elliptical pop tunes and reflecting compellingly on his own travails. Four years later, Trance Syndicate’s Emperor Jones subsidiary released Never Say Goodbye, a mostly fascinating collection of demos of otherwise-unrecorded ’70s and ’80s songs, including six recorded during Erickson’s incarceration at Rusk.

Roky’s situation improved signif-icantly in the 2000s, as he received much-needed medical care and legal aid and eventually made his return to the live stage. 2007 saw the release of Kevin McAlester’s compelling documentary, You’re Gonna Miss Me, which spawned a 12-song soundtrack CD combining familiar Erickson standards with lesser-known rarities; a fine listen, but way too skimpy a selection to serve as a useful overview. Far more authoritative is Shout! Factory’s aforementioned 2005 double-disc set, I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology, which starts with the Spades and ends in the ’90s, covering all of the important bases along the way.

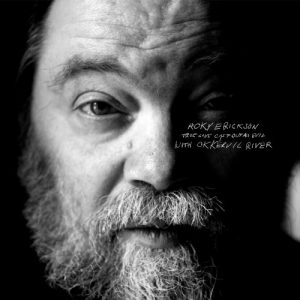

Although I Have Always Been Here Before would have been a graceful valedictory coda to his career, Erickson had at least one more trick up his sleeve. In 2010, he achieved the unexpected feat of blessing the world with another sublime Roky Erickson album, his first set of all-new recordings in a quarter-century. True Love Cast Out All Evil, produced by Okkervil River leader Will Sheff and featuring Sheff’s band as backup, rescues a set of largely-unheard ’70s songs, most of them written during Roky’s stay at Rusk, to create an affectingly reflective song cycle.

Although I Have Always Been Here Before would have been a graceful valedictory coda to his career, Erickson had at least one more trick up his sleeve. In 2010, he achieved the unexpected feat of blessing the world with another sublime Roky Erickson album, his first set of all-new recordings in a quarter-century. True Love Cast Out All Evil, produced by Okkervil River leader Will Sheff and featuring Sheff’s band as backup, rescues a set of largely-unheard ’70s songs, most of them written during Roky’s stay at Rusk, to create an affectingly reflective song cycle.

True Love Cast Out All Evil presents a very different Erickson than the mystic warrior of his Elevators years or the haunted howler of his solo work. With Roky singing resonant, sensitively arranged songs of God, freedom, and bottomless loss in a frayed, vulnerable voice, it’s terrifying, touching, and ultimately triumphant, expanding his remarkable legacy in ways that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier.

Having survived his otherworldly ordeals and returned to the land of the living, Roky Erickson has resumed his life as a working musician, playing shows throughout the U.S. and overseas — as well as in his hometown of Austin — for crowds of adoring admirers, most of whom weren’t born when the 13th Floor Elevators began their explorations of inner space. Whether or not he produces any more new music, his timeless recorded legacy will continue to burn brightly.

MR. RECORD MAN’S TOP 5 ROKY ERICKSON ALBUMS

1. The 13th Floor Elevators, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (International Artists, 1966)

Although not technically the first psychedelic album, or even the first to use the word, this is still ground zero of the psychedelic revolution, and none of the psych outfits that followed equaled the Elevators’ intensity or inventiveness.

2. The 13th Floor Elevators, Easter Everywhere (International Artists, 1967)

The Elevators’ second album is regarded by many as their best. While it lacks its predecessor’s historic status, it features much of the band’s most ambitious songwriting and most adventurous performances, as well as some of Roky’s most possessed singing.

3. Roky Erickson and the Aliens, The Evil One (original release 1980-1981; reissued by Light in the Attic, 2013)

The wellspring of Roky’s brief but potent ’80s resurgence, The Evil One trades the Elevators’ spacy sound and philosophical lyrics for jagged garage-rock sonics, compact melodic craft, and cartoonishly cathartic lyrics whose lurid horror-movie imagery serve as a vivid canvas for the artist’s tortured psyche and fearsome vocal howl.

4. Roky Erickson, Gremlins Have Pictures (original release 1986; reissued by Light in the Attic, 2013)

This diverse compendium of ’70s and ’80s live tracks collects numerous significant non-album songs, transcending its ostensible status as an archival release to offer a vivid, unvarnished account of Erickson’s singular talent and vision.

5. Roky Erickson, I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology (Shout! Factory, 2005)

Smartly assembled by Bill Bentley and Gary Stewart (and insightfully annotated by Bentley), this two-CD, 43-song collection covers all of the bases, from Erickson’s pre-Elevators combo the Spades through his ’90s comeback. If there’s any artist who needed such a collection, it’s Roky, and I Have Always Been Here Before does an admirable job of untangling his convoluted catalog.

No Comment