By Richard Skanse

As milestone birthdays go, 70 trips around the sun certainly merits a fair amount of fuss. A nice family dinner at bare minimum for most folks, and if the birthday boy happens to be, say, the Official Texas State Musician of 2016, then by all means a celebratory bash at a joint just swank enough to convey a sense of occasion a little more special than the average weekend gig. So go ahead and file Joe Ely’s birthday show Friday night (Feb. 10) at Austin’s Paramount Theatre as a pretty big deal — a not-to-be-missed kinda affair for any fan of legendary Texas songwriters of the “Lubbock Mafia” persuasion, right up there with last month’s celebration of Terry Allen’s seminal first two albums, Juarez and Lubbock (on everything), on the same stage.

Ely — whose actual birthday is Thursday, Feb. 9 — was one of Allen’s guests back in January, blowing harp on “New Delhi Freight Train” and singing with the all-star lineup during the two-song encore, and odds are Allen will return the favor at some point during Ely’s Paramount show. Schedules permitting, one or both of Ely’s two fellow Flatlanders — Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock — will more than likely also fit into the program somewhere, along with … well, to be honest, Ely can’t really say just yet.

It’s not that he’s being coy; he just hasn’t ironed out all of those details yet, at least not when I ask him nine days before the big show. Although he has most of his players for the night confirmed — a veritable hall of fame of distinguished Joe Ely Band alumni, from pedal steel wizard Lloyd Maines to guitarists David Grissom, David Holt, and Jeff Plankenhorn — figuring out how to juggle essentially three different revolving combos (and special guests) in and around three different segments covering a span of four-and-a-half decades worth of music is apparently still a work in progress.

“Rehearsal is going to be a bitch,” Ely offers over a late morning cup of coffee at his kitchen table. “I’ve been pulling my hair out over the setlist … but I think I’ve just about got it.”

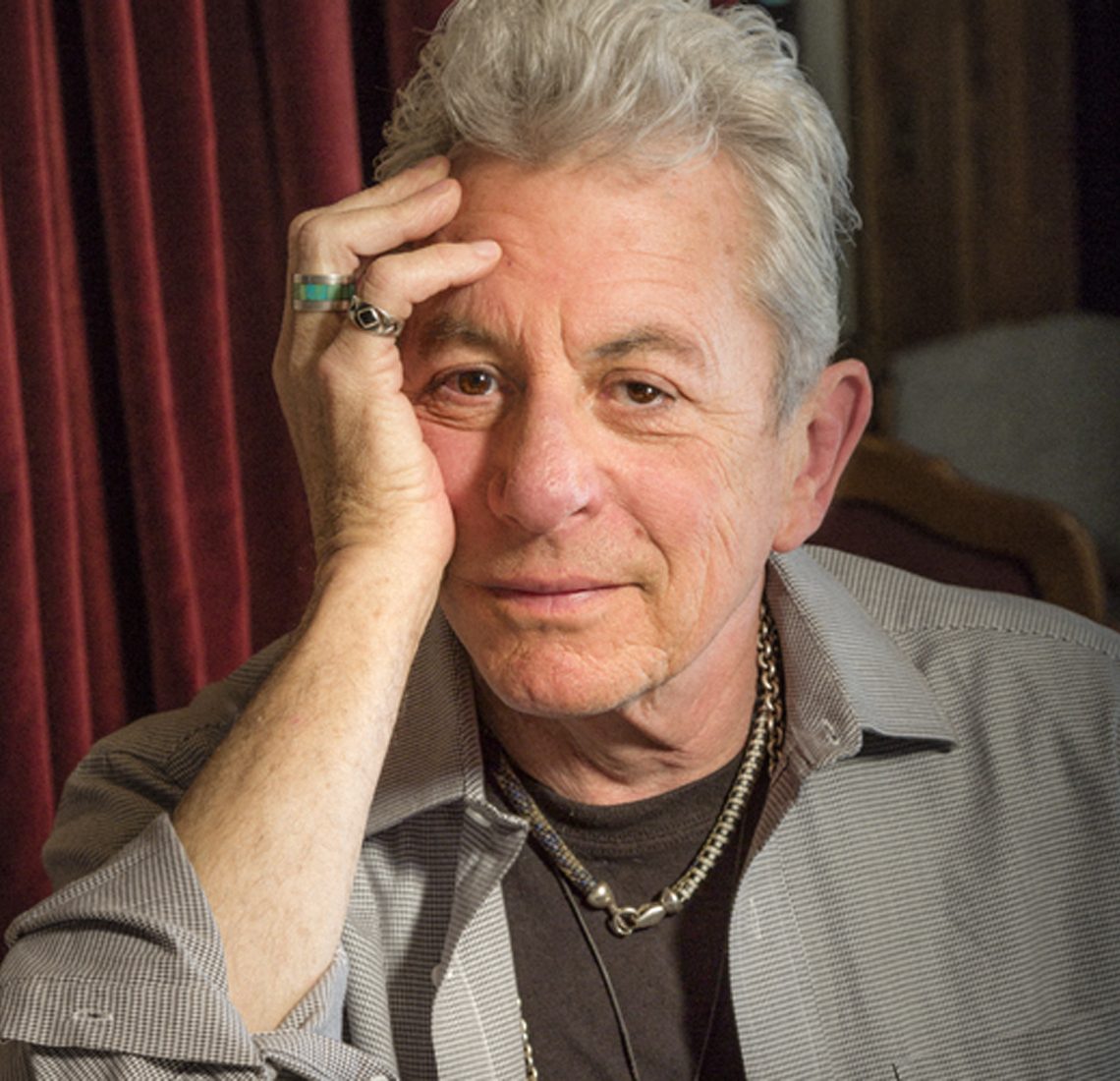

Ely’s hair may be a lot whiter now than the last time I visited with him here at his southwest Austin homestead back in 2011, but it doesn’t really look a strand thinner. And remembering something Grissom told me 10 years ago about Ely always waiting until right before showtime to hash out a setlist based on his quick read of a room, I can’t imagine any of the seasoned band members sharing the stage with him Friday night being caught off guard if he ends up deciding to just wing things freestyle at the last minute. Because that’s just how the Crazy Lemon has always rolled, and even though his birthday blowout at the Paramount will undoubtedly go down as a fat deposit in the memory bank for any lucky fan in attendance, Ely himself really doesn’t seem especially nonplussed by the whole turning-70 thing. Or at least, not anymore than he did about turning 69 — or even 22.

“I had teachers in high school that said I wouldn’t make it to 21,” he explains. “So every one after that has just been … well, I guess turning 40 was kind of a realization that, you know …”

That you’re stuck here?

“Well, yeah,” he answers with a laugh. “But I turned 40 on the North Sea, in February. We were doing a tour at the top of Norway, from the Arctic Circle down, and I was sick of riding in the van because we were skidding around the fjords and there was no guardrail and like, 2,000 feet down to the North Sea. So I went, ‘I’m getting off of this fucking van, man — just drop me off and I’ll catch a bus to Bergen.’ There actually wasn’t a bus, but there was an icebreaker that was going south. So I was waiting there at the ferry stop in Trondheim, looking out at all these chunks of ice floating in the sea, and that’s when I realized that it was my 40th birthday. And I kind of said, ‘You dumb ass — how did you end up in the Arctic Circle on your 40th birthday?’

“I realized that I had no answer for that,” he continues, “but it definitely made getting to 50 and everything after that easier. Because each time I’d look back at that tour traveling around fjords in Norway and think, ‘Well, I can make it another 10 years!’ So now, it’s just another day, you know?”

That mindset, he points out, can really take the pressure off a guy. Once you make it up to — and beyond — a certain point on your lifeline that might have once seemed like Neverland, you sorta realize that you no longer really have to do anything; instead, you only do things because you want to do them.

“That’s kind of been the way I’ve always run my life,” he admits, “but usually I’m so far behind that I have no way of catching up. Now, I just realize that, well, if I die tomorrow, I’ve got most things halfway done, anyway, so to hell with it!”

Rest assured, though, that Ely’s not looking to check out any time soon. Last February, less than a week after turning 69, he suffered a heart attack while riding shotgun with his wife Sharon when they they were running errands in Austin. “I was just lucky to be with her, and that we were only two blocks away from the hospital emergency ward,” he recalls. “But they put a couple of those — what are they called, stents? — in me, and I was feeling better; I was in the hospital for three days, took it easy for a couple of days after that and then went and played a gig.”

Twelve months later, he reckons his stamina maybe isn’t quite what it used to be, “but my blood’s moving better and my actual energy is probably double what it was before. In fact I just went and had my yearly test, and they said, ‘Come back in a year.’ So I feel pretty damn lucky. Whoo!”

Good thing, too, because as has long been the case with Ely, there’s not just a pile of halfway or almost-done projects on his plate that he actually wants to finish, but also just as many new ones he can’t wait to get to waiting in line behind those. Sometimes a newer idea jumps the queue and seduces him into rewarding it priority focus, but often as not he’s happily in his element tending to as many different albums, songs or myriad other creative endeavors as he can at once.

“I’m working on about four or five records right now, and have been for years,” says Ely, who’s probably logged as many hours in his beloved home studio (which fills a small cabin behind his house) over the last three and a half decades as he has on the road going all the way back to his first case of the chronic wanderlusts as a Lubbock teenager. One of those records currently on his front burner has actually been “done” for nearly 30 years; it’s an album of whimsical not-really-lullabies lullabies that he wrote and recorded for his daughter Marie right after she turned 4.

“We actually recorded that one twice,” he says with a laugh. “We started out recording it three days before Christmas, pretty much all day long for two days. I gave it to Marie that Christmas, then I pulled it out about a year later and went, ‘Hey wait, this is pretty good!’ So I got Mitch Watkins, David Grissom, Jimmie (Gilmore), and Glenn Fukunaga in and we re-recorded about half of it. We’ve passed it around to friends through the years — all the neighbor’s kids would borrow it — and I’ve thought about putting it out for a while now, but can never figure out a time. But it’s a fun, funny little record.”

Judging from the three tracks he plays me off his MacBook through a portable Bose speaker on his dining room table, it really is fun — and not at all just in a “better than Barney” kinda way; one track, presumably called “Rock My Baby to Sleep,” features Mitch Watkins playing the main melody on what sounds like a mellotron or synthesized bagpipes, but plug in a Grissom, Holt, or Plankenhorn lead guitar and it’s easy to imagine it blowing the roof off Antone’s or Gruene Hall. Ditto the rousing little number about blowing “Old Mr. Ghost” away, or the one with the gypsy lady reading palms in the candlelight set against the haunting, unmistakable squeal of Richard Bowden’s fiddle. Ely says he’s thinking about pitching the record to an animation studio as a possible soundtrack, but nods and smiles at the notion that adults would probably dig the record even more than kids.

While that album (which Ely says he might title The Milk Maid and the Cowboy, “or something like that”) is finished and just waiting for its moment, the handful of others currently hopping around inside his head and piles of hard drives are all still “in a state of re-arranging and stuff.” “I can’t really talk about them, because I don’t really know them yet,” he says. “They’re telling me what to do instead of me telling the songs what to do. But I know there’s one group that’s kind of a suite of songs from a big city. A lot of those stories came from right after we did that first Flatlanders record (1972), when I jumped on freight trains and ended up living in New York City for half a year; after I came back to Texas I started writing down a lot of that New York stuff, and some of those writings became songs.”

Of course, a lot of those New York writings also made it into print as part of Ely’s first book, Bonfire of Roadmaps, published by the University of Texas Press back in 2007; he later went on to record three different spoken-word albums (complete with sound effects and atmospheric background scores) from the same career-spanning collection of road journals.

Ely says he still writes and records new songs “all the time”; his last album of new stuff, Panhandle Rambler, came out in late 2014, and when asked if the daily Trump Show has reignited his protest fire of late, his teases the title of one particular song he’s working on called “Revenge Creates Revenge.” But meanwhile, his hoard of unreleased material dating all the way back to the early ’70s continues to yield all manner of long-buried gems that are every bit as worthy of his time and attention. Some of it’s stuff he just never got around to finishing, or that he did finish but initially put aside for one reason or another. And then there’s the stuff that he either completely forgot about or didn’t even know still existed.

“Did I tell you about the tapes Lloyd found?” he asks with a grin. He says this right after we first sit down, long before we even talk about his Paramount birthday show or anything else, but as cool Joe Ely things go, it’s worthy of one of the late Steve Jobs’ famous “one more thing …” reveals. It’s a collection of around 26 demos recorded between 1973 and ’74, right between that aforementioned first Flatlanders record and Ely’s classic 1977 self-titled debut — the album LoneStarMusicMagazine.com readers recently voted as the best progressive country album of the ’70s, beating out Willie’s Red Headed Stranger. Some of the demos are solo acoustic; others capture the original Joe Ely Band (both before and right after the introduction of the mighty Jesse “Guitar” Taylor) in full-on, Cotton Club-razing form — as yet unheard outside of the greater Panhandle area but already sounding ready to take on the world. Most of the songs would later be re-recorded for Joe Ely, 1978’s Honky Tonk Masquerade, and 1980’s Down on the Drag, though a few fell through the cracks and haven’t been heard or played live in well over four decades.

That Ain’t Enough: “I had teachers in high school that said I wouldn’t make it to 21,” says Joe Ely. (Photo by Matthew Fuller)

Listening to those tapes today, Ely can remember all kinds of details about who was coming in and out of the nascent honky-tonk band at the time, and how and when most if not all of the songs came to be written, whether by himself or by friends like Hancock and Gilmore. But he can’t for the life of him remember anything about the actual recording sessions for those demos, other than the fact that most of them had to have been done at Lubbock’s Caldwell Studios — save for the solo takes, which “might have been done at a friend of Butch’s.” And he hadn’t thought about any of them in decades, until Maines recently rediscovered them.

“Apparently he had them all this time,” says Ely. “When they moved from Lubbock to Austin, they piled a bunch of stuff in boxes, and they’ve just been moving around still packed away ever since. And I guess he didn’t realize that this one box had these demo tapes that we did way back when. So it’s kind of like The Odessa Tapes that the Flatlanders did, where we would record all this stuff, and then go off and leave it and just forget about it.”

Ely says he’s sent the tapes off to producer Ray Kennedy in Nashville for a few small repairs (fixing a little tape warble here, a dropped channel there), but the handful of tracks he samples for me off of his laptop — including “Gamblers Bride,” “I’ll Be Your Fool,” “Standing at the Big Hotel,” “Fools Fall in Love,” and an alternate version of the Hancock-penned Flatlanders song “You’ve Never Seen Me Cry” (which Ely calls “Windmills and Water Tanks”) — all sound pretty damn great. The acoustic tracks obviously differ the most from the fuller arrangements later recorded for Ely’s first three MCA records, but even the early band tracks reveal layer upon layer of new insight into the evolution of one of the best combos to ever storm out of Texas — the same band that just a few short years later would count England’s The Clash amongst its biggest fans.

Ely cues up the demo recording of “Because of the Wind” that he recently gave to his friend Terry Allen for use in his new installation, “Road Angel” — a surreal jukebox of music and memory in the form of a full-scale, bronzed 1953 Chevy parked in the woods at Austin’s Laguna Gloria. He can’t help but smile in awe at the eerily beautiful cry of Maines’ pedal steel. “Lloyd had already … that’s exactly the way he still plays it now,” Ely marvels. “It’s just uncanny — so complete!”

He stops the song and shakes his head, still smiling.

“Isn’t that amazing?” he enthuses. “When I first heard that, it kind of brought tears to my eyes. Because that whole band … we were just kind of rag-tag, playing on old, beat-up amplifiers and stuff, but it had such a great spirit to it, you know? And those old honky-tonks would all light up and night and get all warm, and the band would start up …

“I’m just really glad these tapes exist,” he continues. “It really helps me kind of see, you know, what happened between the Flatlanders and when we all kind of went off in different directions.”

I want to hear more, and assure him other fans will, too. Ely nods and says he’s thinking about releasing all of the demos together, probably sometime before the end of 2017. And hopefully that 30-year-old album he originally made for his daughter, too. I remind him about the first time he told me about his plans to release his home-recorded original (and superior) version of his 1984 album Hi Res. That was back in 2007, but he didn’t get around to finally releasing the promised B4 84 — volume 5 in his “Pearls From the Vault” series on his own Rack ’Em Records — until 2014.

He laughs.

“Yeah, well, you know … things happen.”

Encantada