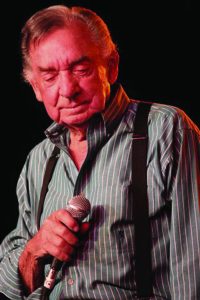

From roadhouses and dancefloor shuffles to concert halls and sophisticated, string-laden standards, the great connector was country music — and Texas music — incarnate.

By Don McLeese

(LSM March/April 2014/vol. 7 – Issue 2)

They say that Texas is a whole ’nother country, and nowhere is that truer than in country music. In Texas, contrasts that would elsewhere seem incongruous — like tuxedos and cowboy boots, steel guitars and symphony halls, respect for tradition and radical innovation — somehow fit together just fine.

I didn’t know how or why that worked before I moved from Chicago to Austin in 1990. Which meant I didn’t really get Ray Price. I would have written him off as another smooth stylist from a bygone era — like Eddy Arnold or Jim Reeves — if I hadn’t had the chance to experience Price as a still vital artist, with a body of work that all held together, in his natural Texas habitat. Where he remained a master of connecting with a song — whether that song was “Crazy Arms,” “Night Life,” or “Danny Boy” — and connecting with a crowd.

He had never lost his interpretive command, nor the innate dignity and decency that had distinguished his music for more than half a century. When I first saw Price perform around the release of 1992’s benedictive Time album, his first in eight years, he was at the top of his game, in command of the adoring crowd that didn’t really think of this as a “comeback.” He hadn’t lost a step; he’d never been away.

Eight years later, when he was 74, he released the even better Prisoner of Love, in which he addressed standards ranging from the title cut to Nat King Cole’s “Ramblin’ Rose” to the Beatles’ “In My Life” to a closing, reverent “What a Wonderful World,” and made them sound all of a piece. I was gone from Texas by then, but Ray Price was by now deep inside of me, and I listened to that album obsessively. I still think it’s one of his best, one that reflects an artistry beyond time or category.

When the artist who had meant so much to country music in general — and to Texas music in particular — died on Dec. 16, some of the obits seemed to scramble to define his significance, his legacy. He was important because he’d been around for so long, and because he’d recorded so many hits (though a whole lot fewer since the ’60s). And he was important because he was connected with so many other artists who were indisputably important, and whose significance was better understood. It was like he had been the last living link between legends, from his formative days rooming with Hank Williams, then inheriting Hank’s band and doing his best to imitate Hank, through the years when his own Cherokee Cowboys nurtured the likes of Willie Nelson, Roger Miller, Johnny Bush, and Johnny Paycheck — all great country songwriters and stylists.

Price himself was never much of a songwriter, but he knew great songs and great songwriters, and he had the knack for taking those words and melodies and making them his own. It was the deep connection with the material — the emotional transparency, conversational phrasing, and bell-like tone of a baritone that could leap into the upper tenor reaches — that turned everything he sang into a Ray Price song, and made every Ray Price song a country song.

So, yes, Ray Price lived a long time, had a lot of hits, and knew some artists who became more famous than he was. And he transformed country music in the process, more than once. If he had only been the man who popularized what remains known as “the Ray Price shuffle,” the 4/4 beat that brought the drums and the walking bass to the fore, packed the dancefloors, and brought Price out of the shadows of Hank Williams’ and Bob Wills’ influence, his pivotal role in country music would be secure. He changed everything with “Crazy Arms” in 1956. And it wouldn’t be the last time.

Just listen to his spoken-word introduction to 1963’s Night Life. In its bittersweet rumination, it could almost be considered a country companion piece to Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours, released the previous year, with both concept albums contemplating the darker side of the night life, the hours after closing time, the truths that bleary eyes eventually must face:

“Tonight, we’ve chosen some of the songs that we sing and play on our dances across the country,” Price tells listeners. “Songs that reflects (sic) the emotion of the people that live in the night life. Songs of happiness, sadness, heartbreak …

“This first song was written especially for me by a boy from down in Texas way,” he continues, as the title cut plays softly behind him. “And it’s accepted so good on our dances, we hope you like it. It’s a little different from what we normally do …”

Yes it was, the song so familiar now, but so new then. And it was “a little different,” a song so bluesy that B.B. King would end up adopting it as an anthem, with a jazzy arrangement featuring some jaw-dropping steel swoops from Buddy Emmons. But the song was as Texas as the singer, and it had been put to the ultimate test — the roadhouse dancefloor — before Price made it the title song of this pivotal album that just might be his best.

It was country music. Because Ray Price sang it. And the bluesiness of the song had been inherent in his music all along, in the lyrics to hits such as “Heartaches By the Number” that weren’t nearly as chipper as the upbeat arrangements.

In retrospect, the album connected the dots between Ray Price Past and Ray Price Future, the evolution of honky-tonk music into America’s music. Because in Texas, country music always was, is, and will be dance music. Price was a roadhouse king, with a regal presence and bearing, and an artist who built a bridge between the dancefloor and the concert hall, where he might be backed by a string section, but the music was as country as ever.

“Night Life” represented a radical departure from “the Ray Price shuffle,” but, as he explains in that intro, it is pure Texas and pure dancefloor. And it was written especially for Price by a musician he’d employed, “a boy from down in Texas way” whose name he didn’t bother to mention because it would have meant nothing to his fans at the time. But he knew a standard when he heard one, and this one from Willie Nelson would be cherished by generations who never knew it was written by an unknown for the great Ray Price.

The maturity and sophistication of “Night Life” made the next phase of his career a natural progression, as sophistication to his ears meant strings, the sort of arrangements that would dilute the musical power of lesser “countrypolitan” artists but enhanced Price’s artistry — his impeccable phrasing, his tone, his intuitive interpretation of the material — while it expanded his audience.

His progression was not without controversy, because the gap for some between “Heartaches by the Number” or other honky-tonk shuffles and his string-laden revival of “Danny Boy” seemed too wide for many to fathom. Yet there’s a purity to the arrangement of the latter that reminds me of the heavenly “The End of the World,” which is about as beautiful as country music gets. And the crossover hit Price enjoyed with “Danny Boy” led to even greater success with his last signature tune, the definitive rendition of Kris Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times.”

It all made more sense when you worked your way backward, as I did when I developed my appreciation for Price after moving to Texas. It was those indie albums he recorded toward the end of the millennium, long after he’d left the national spotlight, that started me down that road. And those albums led to a last hurrah, a return to the national concert stage in 2007, with acolytes Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, as The Last of the Breed (on album, tour, and video). In the public’s mind, Price might have been the lesser artist, the old guy along for the ride. But as his trio mates knew and as the public learned, he was the senior partner, the mentor.

“I told Willie when it was over, ‘That old man gave us a goddamn singing lesson,’” Merle Haggard said to Rolling Stone. “He really did. He just sang so good. He sat there with the mic against his chest. And me and Willie are all over the microphone trying to find it, and he found it.”

As Price himself told writer Michael Corcoran, “The only thing I’ve ever done is sing my kind of song for my kind of people.” And so when Ray Price sang the string-laden “Danny Boy,” it was country music, his kind of song for his kind of people, the kind of people who had known him so long and loved him so deeply in his native Texas. It was country in a way that the great Tony Bennett’s rendition of Hank Williams’ “Cold Cold Heart” never could be.

In the weeks before he died, Price left a message for his kind of people: “I love my fans and have devoted my life to reaching out to them. I appreciate their support all these years and I hope I haven’t let them down. I am at peace. I love Jesus. I’m going to be just fine. Don’t worry about me. I’ll see you again one day.”

At the end, he was a man who was very much at home — with himself, with his legacy, with his family, with his fans, with country music. At home in Texas.

Great article. I have followed Ray since 1966, went to many of his concerts. His music was the best and will long outlive many of todays so called “country artists”.

Thank you for the excellent article. He was the best.

He was one of the best. Saw him at Birthday Parties at Caldwell Auditorium. Know you miss him Mrs. Janie.

He and Tommy Duncan was the best that ever was and ever will be. Both were different but the same. My all time favorites in this singing world.

i saw Ray Price at one of his last concerts a few years ago when he did a benefit for one of his dear friends that had cancer. little did i know that he was suffering himself. he sat on a stool for the concert and sang like there was nothing wrong with him. so glad i got to see him in person before he passed.

Thank you for this tribute to a great singer that

can never be replaced in my heart and mind.

Ray will never be forgotten his voice wow we got to see many many times and he always out did himself.