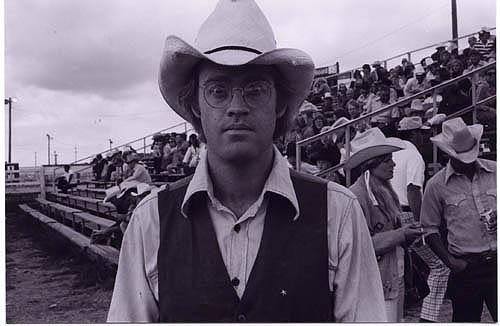

Snapshots, soundtracks and tall tales from Texas and beyond

By Bob Livingston

(LSM March/April 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 2)

First Time For Everything

I didn’t know what to do with myself. I was bouncing between majors; first Art, then RTF, then I tried English. The Vietnam War was raging outside. So far, I was safe from all that, just as long as I stayed in school, made my grades and kept my student deferment from the draft. It was 1969 and I was going to Texas Tech, up in Lubbock. I was obsessed with playing music and getting out of there. Maybe there was a way to do both, and if I ever got the chance, I’d be making tracks … to where I did not know.

The past summer, I’d gone up to the mountains of New Mexico, to Red River, to play in a restaurant bar called the Riverview Inn. It was the first time for everything. I was green; someone called me a hayseed from West Texas I was paid room and board and played for tips. Over the little one-man stage in the Riverview Inn was a sign that read, “Singers’ survival depends on donations.” Nothing has changed.

To supplement these meager wages, I drove jeep tours during the day up to the old ghost mining towns in the high mountains for four dollars a tour. I’d do three, maybe four tours a day. I learned and repeated wild stories to my jeep customers about outlaws and desperados, bank robbers, and hangings in the town square. A train robber named Blackjack Ketchum was hung with some ceremony early one morning, and his head popped right off when the trap door sprung. I got good tips for that tale, and I became a storyteller too …

“The Boys”

One night after my set at the Riverview Inn, ol’ Jack Emory, the owner said, “Come on, Bob, let’s walk down the street, I want you to meet the boys.” It turned out that “the boys’” were a folk trio from Dallas named Three Faces West. They played in Red River every summer in their own club called the Outpost down a dusty dirt back street. They were Rick Fowler, Wayne Kidd and a really funny wise cracker named … Ray Wylie Hubbard. They wore leather pants and leather vests, bandannas and Frye boots — the ones with the square toes. I must admit, I thought they were pretty cool and I wanted to look like them. Ray, Rick and Wayne were great singers and players and were funny as hell. They sang awesome harmonies and did songs I’d never heard before by songwriters they knew personally, mysterious characters with names like Johnny Vandiver, Tom Russell, Kieth Sykes, Buckwheat Stevenson, Ian and Sylvia and a guy from Dallas named Michael Murphey. I thought Murphey’s songs were particularly great, as good as anything I’d ever heard, and Ray and the boys actually knew him. We all became fast friends and we played and sang for the rest of the summer, and I wrote my first pretty good songs with them. Hubbard especially gave me pointers: “Never sit down when you sing, and don’t ever do ‘Early Morning Rain’ again!” I’ve never forgotten.

But in the high mountain passes, the spruce trees were turning blue, a sure sign that fall was upon us and winter was coming fast. So, with the taste of freedom in my mouth, I headed back to Lubbock to get back into school, stay out of the War, and look for an escape.

The Apocryphal Moment

On Dec. 1, 1969, I won the lottery, and my life changed forever. It was the first draft lottery of the Vietnam War and all three TV networks broadcast the event, an old man pulling birthdays out of a big glass bowl. The first birthday drawn was Sept. 14. All men who shared that birthday and were born between 1944 and 1950 were assigned draft lottery number One. If you didn’t have a student deferment, or were blind, deaf, afflicted, or crazy, and you had a lottery number less than 160 or so, then you were probably on your way to Vietnam within a few weeks. The number drawn for my birthday was 309! So I packed my bags and left Lubbock the next day.

Westward Leaning

I headed west, back through Red River, saw the boys for a few weeks and wrote a song with Rick Fowler called “Head Full of Nuthin’” and learned a few new Murphey songs. Next, I tracked further north up to Aspen, Colo., where I played for tips in a bar at the base of a mountain during ski season. My brother, Donald, gave me the gig. Donald was a musician too; he was great at playing and entertaining the crowd, and knew hundreds of hit songs. My family was shocked and concerned about me leaving school, so my brother was secretly watching over me.

One night, after my set in Aspen, a hippy looking dude in a fur coat came up to me and invited me to come to Los Angeles; he said would get me a record deal. He’d been an agent for a lot of Hollywood stars, but he’d dropped acid, left the biz and was spending all his time and money skiing and partying. His name was Randy Fred and he drove a Buick Riviera. I don’t know exactly what he saw in me, but he invited me out to stay with him on a twisty, turny road in the Hills of Beverly.

In another week, the ski season would be over and Randy said he’d meet me at my funky little cabin on the edge of town with further instructions. It was a cold Sunday morning and ironically, even though the ski season had officially ended, it was snowing like hell and the lifts were still open. I was warming up my car and waiting for Randy to drive up. He was over an hour and a half late and I had decided he was not coming. There was a hippie couple that wanted to go to L.A. with me. I told them it looked as though Randy wasn’t going to show and the only other option I had was to go back to Lubbock and finish school. It was a bad option, but I had no other ideas. The hippie couple thought about this for a moment and decided that whichever way I headed, they’d go too. This was the prevailing wisdom of the day, “Leap, and the net will appear.” I waited another 30 minutes and dejectedly prepared to back out of the driveway and head for Lubbock and a sure boring doom as a fifth-grade English teacher. Suddenly, Randy Fred barreled up the driveway in his Buick, all apologies and long hair streaming, handing me keys and directions, saying he’d see me in L.A. in two weeks.

The Hand of Fate

Randy was good to his word and got me a record deal with Capitol Records. They gave me $10,000 in advance and a three-record deal. I bought a Martin guitar and a Datsun pickup truck. I still have the Martin.

I was scared and excited at the prospect of recording my own record and set about writing new songs. A month or so later I had just signed the contract and was driving down a freeway in the middle of Los Angeles when I saw a hitchhiker with his thumb out and a ragged but hopeful look on his face. I usually didn’t stop for hitchhikers in L.A., but this time, the hand of fate reached out and steered my truck over to the shoulder. The hitchhiker turned out to be an auto mechanic from Germany. We got to talking and told each other our life stories. Mine lasted about two blocks. Finally he says to me (in a German accent), “De only otha Texan I knoow is from Dal-las. He’s a musician too. His name is … Mike Murphey.”

It was an amazing and synergistic stroke of luck, or fate, or what ever you want to call it. I gave the German mechanic my number saying if he ever saw Murphey again, to give it to him. That night, Murphey called me up and asked who I was and what I was doing in L.A. He said he lived up in the Mountains above the desert in Wrightwood and he invited me up for a visit. I ended up moving up there and we became friends and wrote and played together. Later on, we started a publishing company with Guy Clark and Roger Miller called the Mountain Music Farm. Nothing much came out of this endeavor except that I was writing songs, playing at folk clubs and having an amazing amount of fun.

Murphey was a great singer, musician and songwriter. He was soulful, had a lot of his songs cut, including a hit for the Monkees, and thought about songwriting and playing music all day. He was a great example for me and he helped set the tone of my life’s course.

There was nothing left to do …

A year later, my record deal with Capitol fell through. They fired 152 artists and I was one of them. They bought me out of my contract and sent me on my way with no advice or reason for their actions. Murphey had had some disappointments, too, so he asked me to go back to Texas with him for some gigs. He handed me a 1972 Fender Bass guitar, and from that moment on, and for the next 35 years, I would be a bass player in a band rather than my own man. But at the time, this seemed to be a big step in the right direction.

Murphey and I played all over Texas and Colorado that summer. There was a lot of buzz about him and he got a record deal with A&M Records. We went to Nashville and cut a album called Geronimo’s Caddilac and moved to Austin. It was 1971 and Austin was a creative boom town; the streets were full of musicians, poets, dancers and artists. We all hung out at the Les Amis Café. Austin had a great live music scene even then. Clubs like the Checkered Flag, the Vulcan Gas Company, the Armadillo World Headquarters, Mother Earth, the Jester. There were folkies like Murphey, Richard Dean and Townes Van Zandt and there were rockers like John Inmon, Rusty Wier, the Stahaley brothers and Gary P. Nunn. Soon we had a band that mixed all these influences into something new. Gary P. joined us. Craig Hillis, Michael McGeary and later Herb Steiner also joined up.

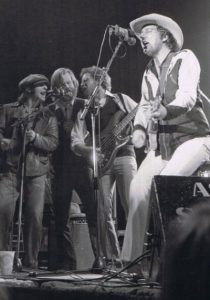

One day, at a band rehearsal with Murphey, a folksinger from upstate New York named Jerry Jeff Walker peeked his head into the rehearsal room and saw, “instant band!” He told us he’d written some new songs, and would like us to play on his new record. The album that we recorded in Austin and New York was Jerry Jeff’s first MCA record, simply titled, Jerry Jeff. Songs like “L.A. Freeway,” “Charlie Dunn” and “High Hill Country Rain” were all recorded live and haphazardly in the studio. This record took off and gave Austin a lot of notoriety. Murphey and Jerry Jeff were reigning princes and the now-called “Austin Interchangeable Band” was playing with both of them. Joe Gracy, who ran the best radio station in town, KOKE-FM, coined the term “progressive country” to describe the sound. Others called it “country rock,” “Outlaw” or “cosmic cowboy” music, but I always thought of Jerry Jeff as the first punk rocker.

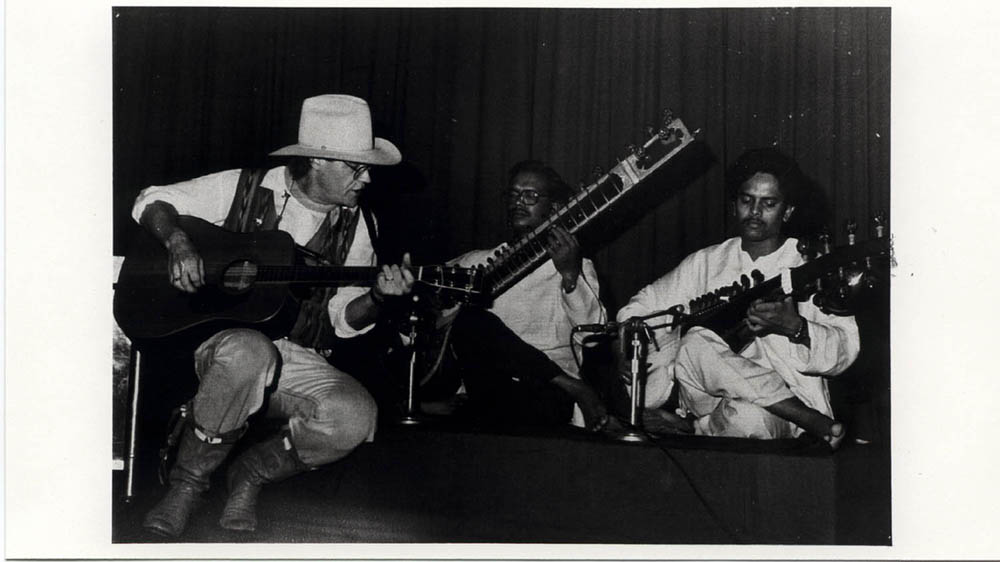

In the end, we formed the Lost Gonzo Band and threw in our lot with Jerry Jeff, for better or worse. I played with Jerry Jeff on and off for the next three decades. I did a lot of other music during that time too, including recording and playing with the Lost Gonzo Band and Ray Wylie’s new Hot Texas Band. I also toured internationally on my own to countries like India, Pakistan, Africa and the Middle East for the U.S. State Department. I adopted a multi-cultural view of our world in sharp contrast to the shit-kicking honky-tonks I played with Jerry Jeff, Ray Wylie and others.

Jerry Jeff and I parted ways in 2006 and I put out a CD influenced by my experiences in India called Mahatma Gandhi & Sitting Bull — an album title guaranteed to ruin your chances of any airplay in Lubbock.

Be Here Now

These days, I’m a folkie and just released a new CD called Gypsy Alibi on my own label, New Wilderness Records. I’m doing better on my own than on any record label I was ever signed with. The album has a bit of everything on it: folk, from my Red River days; the kind of Americana country that I lived on the roadhouse circuit; rockabilly; Texas swing and even a Gershwin-inspired piano track as the title song.

To make a living in the music business in Austin today is not an easy proposition. They say it’s “The Live Music Capitol of the World.” There are literally thousands of musicians here all hustling to survive in a fast, competitive climate. Radio is not as local friendly as it once was. As one Nashville record man told me at SXSW, “Austin is a great party town with music even in the bathrooms, but if you want to get business done, you gotta to go to Nashville, New York or L.A.” I don’t know.

Some musicians manage quite well in this climate, most notably Bob Schneider, Eric Hokkanen, Redd Volkaert, Earl Poole Ball and maybe a hundred others that play every night somewhere and don’t have a day job, but they seldom leave the Austin city limits. I have never really made a living in Austin even though I’ve lived here for almost 40 years because I still love being on the road, and I have more of a draw in Bristol, Va., and Fayetteville, Ark., than in my own town. I play here occasionally, but tour most of the year. I hope to play here more now that my new CD is getting airplay on KUT, KGSR and KOOP.

My spirit of adventure takes me on roads all over this country and internationally to more than 30 countries now, exotic and spectacular places like Vietnam, Africa, and the Middle East. Far, far from Lubbock, Texas! To make it all work and pay for my house, I play folk clubs, house concerts, do sessions, voice-over work, kids shows, folk festivals, give workshops and play the occasional bass gig in a touring country band.

A friend of mine, Lee Roy Parnell, once told me, “Bob, the reason I left Austin for Nashville is because I couldn’t get a $35 a night gig at the Aus-Tex Lounge, so I had to leave or never have the chance of making it.” I don’t know if this is true for everyone, but it’s been true for me as well. From the get-go, I had to make tracks. No regrets about that. None!

You’ve really paid your dues, Cosmic Bob! Hope you continue on your musical journey.

May your music set you free.