By Laurie Barker James

(LSM Sept/Oct 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 5)

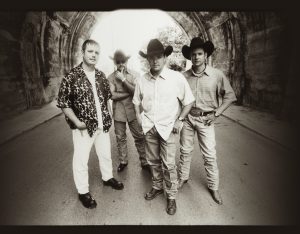

Before Jason Boland and the Stragglers, before Stoney LaRue and Brandon Jenkins, and before that other four-piece band from Stillwater, there was the Great Divide. Firmly entrenched north of Austin and definitely left of Music Row, the band’s original three CDs were produced in the early 1990s by Texan super-producer Lloyd Maines. Although the Great Divide splintered and imploded at the early part of the last century, they are still considered a seminal influence on most of the bands that have come out of the OK state, and any band that values substance and creativity over flash. The band, fronted by Mike McClure, broke up several years ago, but thanks in part to sobriety and prayerful forgiveness, the Great Divide reunited on Aug. 26 for an appearance at the weekend-long Stillwater College Days festival. (The festival also featured LaRue, Boland, Pat Green and Reckless Kelly, and a live CD/DVD compilation is expected to be released.)

Although it wasn’t as unpredictable as, say, the Eagles “Hell Freezes Over” reunion, people who knew the band back in the day were no doubt a little surprised to learn that wild-child Mike McClure was sharing a stage again with his former band. Perhaps nobody was more surprised than the individual band members themselves: Several of the guys hadn’t actually spoken with McClure since he left the band eight years ago.

The Great Divide arguably influenced almost every Oklahoma band over the last two decades. Boland, who came to Stillwater to write at the height of the Divide’s popularity, cites their impact on his own band, the Stragglers. “Their originality was the biggest influence on us,” Boland says. “The music was special, personal, and (the band was) not trying to copy someone else’s success.”

“They were the first band that I knew doing their own thing,” adds Cody Canada, who went on to spearhead two groups, Cross Canadian Ragweed and the Departed, that are pretty much known for doing their own personal brand of thing. “They gave me tons of encouragement and hope.”

In the beginning, it was just four guys from Oklahoma. Brothers Scott and J.J. Lester (rhythm guitar and drums, respectively) along with bassist Kelley Green, joined forces with singer-songwriter McClure, tentatively gigging around the area in the few clubs available at the time. They gathered at a place called the Farm, a ramshackle house owned by a guy named Danny Pierce. The late, great Oklahoma musician Bob Childers lived on the place in a travel trailer. For a decade before the formation of the Great Divide, musicians passing through could swap songs, tell stories around a campfire, and maybe get a meal. McClure, who hails from Tecumseh, says the hippie environment was heady. “It was kind of a different culture than my small town,” McClure says.

McClure was, by default, the primary songwriter. Scott Lester recalls the first time he heard McClure play. “Mike is one of the best songwriters I‘ve ever heard,” he says. “The first song he sang, in my living room, just him and his guitar, was ‘Lookin’ on Back,’ about his grandparents. I was sucked in right there. Mike put into words what the four of us were living.”

But everyone had a band-connected job. J.J. Lester was in charge of booking the gigs, while his brother Scott, a fireman, was the default mechanic for the van vehicles, and Green was nominally in charge of marketing. The Great Divide’s first record, 1994’s Goin’ For Broke, was recorded on a shoestring and distributed by Campfire, a label in Texas which also distributed two of the band’s honky-tonk heroes, Gary P. Nunn and Jerry Jeff Walker.

“When (Campfire) agreed to distribute the record, we thought we had it made,” J.J. Lester says. The band’s CD proved a hit with the local Cowboys who populated Oklahoma State University.

“We were fortunate to be in a college town,” Scott Lester says. “We learned to attack college markets. At the time we started, Mike and Kelley were still in college.”

College kids bought the music, and came to see the band. When they went home over the summer, they took the CDs back to wherever they were from, and the Hastings store in Stillwater became a kind of distributor for Hastings stores in two states, where other kids would go to try to get the CDs. Green went from selling the CDs on consignment to having the local store buy cases outright to fill the demand. And that propelled the Oklahoma band without a real recording deal onto the national SoundScan.

Nashville eventually came calling, lured by the band’s do-it-ourselves attitude and instant, seemingly endless popularity in the college markets of the Southwest. Atlantic Records re-released the band’s second album, Break in the Storm, as the Great Divide’s first national CD in 1998. The breezy “Pour Me a Vacation” was a hit, both on radio and on the new medium of CMT.

But the guys learned a hard lesson when Atlantic’s recording division split in 1999, just as they were gearing up to promote their third effort, Revolutions. Although contractually tethered to Atlantic (owing five more discs), it was clear which way the wind was blowing. “Atlantic Records did not know what to do with us and how to market us,” Green says. “They tried to find a new idea or gimmick instead of just promoting us straight.”

Broken Bow, the current home to Jason Aldean and American Idol contestant Kristy Lee Cook, picked the band up, but the then-fledgling start-up label didn’t have any better idea of how to market the band. At some point in the early part of the last decade of the last century, the Great Divide lost whatever magic drew them together, and splintered. McClure left in 2003, tired, disillusioned and wasted.

“The story of the demise of the Great Divide is not original — we certainly didn’t pioneer the breakup,” says J.J. Lester.

“I gave them six months. That was a long six months,” McClure says, with a laugh. “I just wasn’t happy anymore, so I went to my basement and made records. As a songwriter, you have to follow your calling. But it was hard for everybody.” He went on to release several solo albums, as well as write with and produce albums with artists including Boland, Cross Canadian Ragweed and Javi Garcia.

In the wake of McClure’s departure, the Great Divide soldiered on for a few more seasons with replacement singer Micah Aills. “We weren’t ready to call the Great Divide quits,” Green says. “Anytime a band loses a member there’s going to be a different sound, whether you want that or not. But we would have regretted not trying.”

After the rest of the band finally called it quits, J.J. Lester did some production work himself (for the Eli Young Band and No Justice) and became a college pastor. His older brother Scott now owns a welding company and a construction business, along with a horse ranch. Green became an AutoCAD technician. For almost a decade, the band members didn’t speak much, or socialize.

When a band breaks up, the cliché is that it’s like a divorce. But for the Great Divide, it was also a rending of family — family by birth, in the case of the Lester brothers, and family by choice. “Brothers out on the road — they don’t like each other all the time,” J.J. Lester says. “You can love without liking a whole lot.”

The first step toward the reunion, ironically, came last year, with McClure admitting he was an alcoholic. “I’ve been sober for 16 months — I was tired of being a drunk,” he says. “It’s easy to be drunk all the time. Musicians have to watch it. (Constant drinking) is accepted but not necessarily a good thing.”

McClure reached out to his three former band mates via email, and J.J. Lester says that olive branch was like breaking down a wall. From casual conversations to planning a gig at a venue owned by a mutual buddy, the dominos that led to the reunion all fell into place.

For many who love the Red Dirt scene, the Great Divide’s reunion means a return to the basics of that particular brand of music. Justin Frazell, who hosts the Texas Red Dirt Roads radio show, is a little nostalgic for the time two decades ago when “the passion for the music was real.” Whether it’s the easy availability of gigs almost anywhere or the quick-as-lightning internet marketing, Frazell says that the scene has become “watered down because people think it’s easy” to create music, perhaps without putting in all the miles on the road. “The reunion of The Great Divide relights a fire that has smoldered in the Texas/Red Dirt scene for a while,” he says.

Nevertheless, when asked whether the reunion will produce anything more than that one-night gig in August, all the band members are fairly taciturn.

Green says that, while the reunion feels good, “we’re not ready to jump on a bus and do 200 shows.”

“I don’t think any of us want to do It for a living again,” Scott Lester adds. “But we enjoy each other.”

No Comment