By Richard Skanse

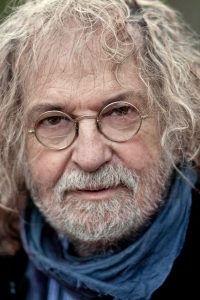

It’s long after dark on April 1, 2015, and Ray Wylie Hubbard is striding up my gravel driveway through sheets of rain looking for all the world like … well, like he pretty much always does: equal parts grizzled gypsy, Old West gambler and Steampunk pirate. Anyone not knowing better, especially on a night like this, might go so far as to say he looks like trouble — the kind of trouble whose knock on the door, timed just right with another crack of thunder and flash of lightning, could spook a jumpy agnostic into hiding in a corner and singing gospel songs.

I open the door and welcome him in.

His usual wild mop of shaggy hair hangs limp, beaten down by the rain, but his eyes dance with mischief behind the blue-tinted lenses of his John Lennon spectacles. “You ready to do this?” he asks straight away, stooping to scratch a curious cat behind the ears but eager to hit the road. “You have an umbrella? It started really coming down as soon as I left Wimberley, but George said it’s not raining at all up at his place, so it should clear up on the way to Austin. If it gets any worse we’ll head back and I’ll have to reschedule, but I’d really like to get this done tonight because Carson leaves town tomorrow, and I want her in this thing.”

By “George,” he means bass player George Reiff, one of Hubbard’s favorite stage and studio collaborators and the co-producer of his last three albums: 2010’s A. Enlightenment, B. Endarkenment (Hint: There is No C), 2012’s The Grifter’s Hymnal, and The Ruffian’s Misfortune, at the moment still a week away from release. Carson McHone is the spitfire young Austin country rocker who sings backup on the new album’s “Chick Singer, Badass Rockin’,” a riotous salute to fierce women rockers from the Runaways to Chrissie Hynde and beyond that Hubbard is hell-bent on shooting a video for tonight, pounding April showers be damned.

“There’s some other great singers I could have used, like any of the Trishas, but what I really wanted was like a female Keith Richards — somebody to just do a high Keith Richards slur, you know?” Hubbard explains as we merge onto I-35 for the 40-minute drive from San Marcos to North Austin. “And George found Carson and she just nailed it.”

She’s ready to nail it again when we arrive at Reiff’s home studio. Pleasantries are exchanged as Hubbard presents Reiff with a vinyl copy of The Ruffian’s Misfortune — his first record pressed on wax in 30 years — but McHone’s got a gig downtown in a couple of hours, so she and Hubbard get right to work. Tonight’s shoot is an exercise in money-is-no-object excess, with literally tens of dollars charged to Hubbard’s Bordello Records AmEx on everything from the $1.99 8 mm app on his iPhone to the Joan Jett Hot Wheels big rig he nabbed off eBay for $20. The cymbal-clapping toy monkey used in his video for 2012’s “Coricidin Bottle” makes a cameo, too, along with BrownBox and SexDrive guitar pedals from Hubbard’s own kit bag (“Product placement!” he cracks with a conspiratorial grin.) Hubbard does most of the filming himself, except for when he needs footage of him and McHone singing the chorus together.

“Flick the screen to make the ‘film’ jump,” he instructs between takes. “Do that as much as you like.”

The mood he’s aiming for can best be described as “artful hot mess.” The finished video, meticulously edited by Hubbard in iMovie and premiered on YouTube a couple of weeks later, proves as sloppy cool by design as drummer Rick Richards’ rag-tag, gut-bucket street beat, which threatens to knock the needle clean out of the groove every time Reiff cues the song up on his turntable and cranks it to 11 for Hubbard and McHone to sing along to in the other room.

“Ray always wants things to be good, but he never wants them to be too good,” Reiff explains with a smile. “I was really happy with the fact that I forced Rick Richards — who’s one of the best drummers ever — to play like a 16-year-old kid in a garage band for this. And Ray … I don’t know if anybody’s ever heard him do a song quite like this, as aggressive as this, before. But I really wanted that represented on the record, because that’s a part of who Ray is.”

After a decade of working together, Reiff has a pretty good handle on who Hubbard is and what makes him tick. “It’s a pretty funny dynamic,” he says of their co-production work, be it on Hubbard’s own records or projects for other artists seeking a little of that patented Ray Wylie “grit ’n’ groove.” “The way it works is, I run around and make stuff sound good and plug things in, and he’s the big picture man: He kind of sits there in the producer’s throne and goes, ‘Well, I think you need to make it more … greasy.’ And whatever artist we’re working with will kind of scratch their head, but I know exactly what he means.”

Grease, grit, and groove have been the primary colors on Hubbard’s sonic palette now for well over a decade, and The Ruffian’s Misfortune — his 16th album and third on his own Bordello Records label — in large part follows suit. That accounts for why he’s picked the righteously cool “Chick Singer” as the album’s video-worthy lead focus track: Hubbard’s flair for self-deprecating wit is as genuine as it is endearing, but so too are his hot flashes of grizzled Jedi swagger that taunt, “rock this hard when you are pushing 70, you will not!”

“There’s actually a couple of songs on this record that sound like a 22-year-old punk guy,” Reiff enthuses — the other being “Bad On Fords,” an uproarious growler about a libidinous Oklahoma car thief on the prowl. Hubbard likes to tell the story of how he came to co-write that one with country singer Ronnie Dunn (aka “not the one with the hat”) and how Sammy Hagar beat both of them to recording it first. But Hubbard’s version on Ruffian’s is definitive, and after a month of listening to an advance copy of the record, I’m convinced that both of the new rockers are certifiably badass enough to give the indomitable “Snake Farm” a run for its money as fan favorite staples of Hubbard’s live shows. Hubbard seems to think so, too. On the drive home from Reiff’s that night after the video shoot, he reveals that his booking agent is close to landing him his third appearance on national late-night TV in as many albums, and he reckons that come June, “Chick Singer, Badass Rockin’” oughta be as fun to play on Conan as “Mother Blues” was on Letterman in 2012 and “Drunken Poet’s Dream” was on Fallon back in 2010. At the very least, he promises, “it’ll be pretty trashy!”

By the time his Conan debut rolls around later that summer, though, Hubbard has opted for something completely different. Accompanied by his son Lucas on mandolin, Lisa Mednick Powell on accordion, and Kyle Schneider on drums, he uses his golden moment in that spotlight not to rhapsodize about Telecasters, sticky fingers and torn stockings, but rather to meditate on forgotten saints, lost souls and red-winged blackbirds whistling “oh that I might die.” Part prayer, part unrepentant last will and testament, it’s a song for the fallen called “Stone Blind Horses,” and it sounds nothing at all like something a “22-year-old punk guy” could ever come close to pulling off. But Hubbard delivers it with the authoritative conviction and gravitas of a battle-tested and world-wizened wayward gypsy/grifter/poet/shaman, because yeah, well … he pretty much is.

* * *

He was born in Oklahoma … Hugo, specifically — 69 years ago this past November.

And then, 41 years later, Ray Wylie Hubbard was born again.

Perhaps not quite in the strict fundamentalist sense; hell, not even remotely. As Hubbard recounts in strikingly candid detail in A Life … Well, Lived, the compulsively readable autobiography he published in early November, there were certainly 12 steps involved, with various demons shed like dead skin en route to a conversion he unabashedly calls a “spiritual awakening.” But he didn’t turn all holier than y’all or go changing all the station presets on his car radio. And he for damn sure didn’t stop playing the devil’s music for a living. But make no mistake: The Ray Wylie Hubbard that has walked the earth for the last quarter century is an entirely different animal — and artist — than the one that came before.

Well, give or take an old joke or two. In his book, Hubbard recounts a very early gig he played with his first band, a just-out-of-high-school folk trio called the Coachmen (later to be renamed Three Faces West). In order to pad out their thin set list, Hubbard’s bandmate Rick Fowler told him to kill time by telling the audience “about your Okie hillbilly dumbass self.” After a panic and a long, uncomfortable pause, he stammered something about his Oklahoma grandfather being a bootlegger: “He smuggled books into Arkansas.”

That was 50-some-odd years ago, but odds are Hubbard used the same bit in front of whatever audience he faced last weekend. “It’s old, but man, it still works,” Hubbard says today with a laugh. “If you get a good horse, ride it!”

For the record, he doesn’t have any songs quite that old still in his regular repertoire, with most of his originals from the first 20 years of his career having long since been put out to permanent pasture. But one hoary old nag still gets a regular workout, and no matter how many times he’s playfully disparaged it over the years, don’t be fooled for a minute into thinking Hubbard himself is any more immune to the simple charms of “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” than you are. “It is kind of cool,” he says, acknowledging the rush he can still get from lighting up a room with shit-eating grins the moment he hits that opening G chord. “People sing along, and you see them smile and laugh, and that’s gratifying, just knowing that it’s enjoyed. And, at least it’s not ‘Feelings.’ I don’t think I could sing ‘Feelings’ every night for 40 years.” (That’s actually a pretty well worn stage quip, too. “The way I see it,” the rest of it usually goes, “careers have been built on less … I wonder what Vanilla Ice is doing tonight!”)

Hubbard never actually meant for “Redneck Mother” to be any more than a laugh in the first place; he didn’t “write” it so much as spew it, venting his rattled nerves in a friendly guitar pull mere minutes after returning from a harrowing beer run in which he really very nearly did get his hippie ass kicked in a bar full of certified bubbas (and one bubba’s mama) in Red River, N.M. And that guitar pull probably would have been the end of it, too, had one of the other musicians in that afternoon’s hootenanny not been Bob Livingston, who carried the song in his head back to Texas and introduced it to one Jerry Jeff Walker. It was Walker’s live cover of “Redneck Mother” on 1973’s seminal ¡Viva Terlingua! that sealed the song’s fate as a progressive country classic, and Livingston’s slow-drawl intro — “This song is by Ray Wylie Hub-berd” — that punched the author’s ticket to infamy. (The following year, Willie Nelson, Jody Payne, and Mickey Raphael sang the song together at the taping of the pilot episode of TV’s Austin City Limits.)

The mid to late-70s were high times (in every sense of the term) for renegade songwriters of the Texas persuasion, and Hubbard — a folk-loving hippie gypsy with a rock ’n’ roll heart — fit right in from the get-go. Having played in various acoustic combos throughout high school and college in and around Dallas (along with formative summer residencies in Red River), he could pack a club and rabble rouse as convincingly as any three-name headliner of the era — especially when leading (more or less) the misfit posse that called themselves the Cowboy Twinkies. A typical night would find them veering recklessly from Hubbard originals (“Redneck Mother,” “West Texas Dance Band”) and Merle Haggard covers straight into Zeppelin’s “Communication Breakdown” and Hendrix’s “Purple Haze.”

“I remember one night when Ray just sat down on the side of the stage and the rest of the band decided to just do Beatles songs,” recalls fellow Oklahoma-born songwriter Kevin Welch, who now lives a short walk up the road from Hubbard in Wimberley. “That was back in his uproarious days; he was pretty legendary. But that was kind of par for the course back then. It wasn’t just Ray — it was pretty much everybody that was getting onstage, and it was definitely everybody that was in the audience.”

Unlike many of his peers on the Texas scene, though, Hubbard never could catch a real break as a recording artist during those heady boom years of redneck rock and outlaw country. The Twinkies were courted by two major labels, but sessions for an Atlantic record stalled before they got out of the gate and the self-titled album they did see to fruition with Warner/Reprise ended up being released with so much studio sweetening (most notably, a cloying dollop of overdubbed female backing vocals) that the broken-hearted band literally cried when they heard it. A couple years later, Hubbard spent about 15 minutes on pal Willie Nelson’s short-lived Mercury imprint Lone Star Records, just long enough to pull together some scattered demos (and a Willie-requested recording of “Redneck Mother”) for 1978’s Off the Wall. After that, Hubbard ended up releasing both 1980’s Something About the Night and 1984’s Caught in the Act — a live album financed by a drug dealer fan who just wanted a cassette to play in his Mercedes — more or less on his own, which back in those days at least was about as good a way as any to ensure that almost nobody knew you had a new record out.

But Hubbard had a lot more weighing on his mind in the mid-80s than just trying to move records. His first marriage had just ended after a six-year run, and though he took the divorce itself well enough in stride — staying on remarkably good terms with his in-laws, at least — seeing his young son Cory move some 30 miles away with his ex-wife after she remarried was rough. Even harder was the death of his father, which left Hubbard, an only child, orphaned at 38. To numb the grief, he double-downed on the alcohol and cocaine habits that he’d nurtured throughout the better part of his adult life. And on top of it all there was the matter of his nagging insecurity about not only the state of his career but his own artistic merit. Although he could still muster great players — from the Lost Gonzos to ex-Mouse and the Traps guitar hero Bugs Henderson — and charm a crowd even with his mind numbed in a chemical haze, Hubbard was finding it harder and harder to swallow his own snake oil.

“I was in this make believe world I had created for myself,” he writes in his book. “It was a dark kingdom where I thought of myself as a Keith Richards cool drug rocker, a Townes Van Zandt tortured songwriter, a Dylan Thomas heartbroken poet. The reality was that I was just a sloppy blackout drunk playing ‘Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother’ twice a night in these shitty honky-tonks and seedy bars in Forth Worth and Dallas and Oklahoma, where the patrons drank like I did.”

At his absolute nadir, Hubbard even mulled thoughts of suicide. Then he gambled everything on trying something that at the time probably seemed even harder: sobriety. Stone cold turkey.

“The 12th of November, 1987, was my last drunk,” he says. “I don’t really remember much about it, but Nov. 13 is my birthday, so I was blackout drunk at 40, then I turned 41 and haven’t had a drink since … or a drug.

“It was just time,” he says matter of factly, setting up another familiar Hubbardism: “I’d had all the fun I could stand.”

Six months and eight-out-of-12 penitent program steps later, Hubbard fell hard for a woman he met at an AA meeting. The attraction was mutual. Judy Stone, daughter of Dallas car dealership magnate Eddie Stone, was a decade-plus younger than Hubbard but already had eight years of sobriety under her belt; she had had all the “fun” she could stand by the wizened age of 22. But she still had a sense of adventure and a soft spot for “bad boys,” and Hubbard — fresh out of the fire, frayed around the edges and scrambling to get his ducks in a row — fit the bill.

“I always used to tell my dad, ‘You know, if I could just meet a nice Christian biker that didn’t go to church …,’” Judy recounts with a laugh. “Because I wasn’t a church person, but I wanted someone with old-fashioned morals, you know? And that was Ray. He was an outlaw, but he was a gentleman and an old soul. From the first time I went out with him, he just seemed like somebody that I’d already known for a really long time.” They married a year later.

As his manager and de facto record label boss (not to mention the mother of second son and sometime lead guitarist, 22-year-old Lucas), Judy’s the one largely in charge of keeping Ray Wylie’s ducks sorted now. But there wouldn’t be much of a Ray Wylie Hubbard career to manage at all these days had he not committed to a bonus 13th step on his road to rebirth. At age 42, two decades and change into his professional songwriting and performing career, Hubbard manned up, swallowed his pride and signed up for his first real guitar lesson. After years of making do with basic chord strumming, he made a concerted effort to learn how to fingerpick. It was like the lifting of a veil.

“What I first noticed after he started fingerpicking was that he no longer felt insecure if he didn’t have a whole band or a sideman with him onstage,” notes Judy. “That freed him up to go anywhere and do anything; all he needed was a guitar. And I could tell a real confidence change, where if he got asked to do a song swap with somebody, he wasn’t feeling like, ‘Oh God, I gotta play “Redneck Mother” to get the crowd to like me because my guitar playing sucks.’

“And then once he wrote ‘The Messenger,’” she continues, “things really changed.”

“‘The Messenger’ was a big breakthrough for Ray,” seconds Welch. “I think that’s when he realized what he would really be able to do working in the song form.”

The proof is right there on record. By Hubbard’s own admission, the main purpose of 1991’s Lost Train of Thought was to let people know that he wasn’t “dead or drunk or dead drunk,” and the album’s mix of raggedy dancehall honky-tonk and spirited “Rockabilly Rock” picked up more or less where he left off in the ’80s before getting his life back in order. But the second release of his sober era, 1994’s Lloyd Maines-produced Loco Gringo’s Lament, was another matter entirely. From the haunting, cinematic sweep of the opening “Dust of the Chase” through to the Rainer Maria Rilke quoting “The Messenger,” this was a record unlike any he’d ever made before, signaling something far more than just a competent comeback: It marked his ascension from journeyman outlaw to the rarified rank of philosopher-poet songwriter’s songwriter. Dangerous Spirits (1997) and Crusades of the Restless Knights (1999) followed exacting suit, with Maines’ keen ear for clean acoustic arrangements neatly complementing Hubbard’s precision-tuned lyrical profundity and wit in songs like “Last Train to Amsterdam,” “The Ballad of the Crimson Kings” and “Conversation with the Devil.”

Hubbard’s writing would only get stronger moving forward, but his music took a hard left turn into grittier, bluesier territory beginning with 2001’s Eternal and Lowdown. Resonator slide supplanted acoustic 12-string as his main weapon of choice, with open tuning his new musical addiction and kindred spirit Gurf Morlix stepping in to play both producer and simpatico enabler, greasing his slide into the primordial ooze of 2003’s Growl and the relentless grooves of 2006’s Snake Farm. Nine years and another four records down the line, Hubbard’s still panning those muddy waters for gold, be it songs or maybe even another magic chord like the one he rhapsodizes about for a full two pages in his book — the one he calls “the secret to the universe.” (Spoiler: It’s the “E without the third.”)

“He still loves to fiddle around on the guitar,” Judy observes, then laughs. “I mean, who do you think it is that sits next to him on the couch? It’s not me. It’s the guitar! He woodsheds every single day. He’ll pull up instructional videos by fingerpicking experts, or Lightnin’ and Mance Lipscomb, people like that, and he’ll get on his guitar and watch those with his headphones on to learn what they’re doing. He stays up until 1 or 2 a.m. every night, just trying to figure out Lightnin’ Hopkins.

“I don’t know if it’s a work ethic thing or just that thing writers have where they have to write,” she continues, “but he’s just driven. And he still really loves what he does.”

That love (and drive) has not been in vain. Although Hubbard’s career has been on the upswing ever since he went sober, it wasn’t until Snake Farm that he fully came into his own as the widely revered elder statesman of Americana he is today. He’s never been anywhere near the Billboard 200, let alone snagged a Grammy, but he can count amongst his notable fans both Beatle Ringo Starr (who gave Snake Farm a thumbs up on his own website) and Eagle Joe Walsh, who was so impressed he snatched up Hubbard’s rhythm section of Reiff and Richards (band poaching being arguably the second sincerest form of flattery). And as for the first form, well, suffice it to say that not since Robert Earl Keen unwittingly launched an entire generation of imitators has one artist’s sound echoed so loudly through the entire Texas music scene; you can’t swing a “Screw You, We’re from Texas” T-shirt at MusicFest or KNBT’s Americana Jam these days without hitting a young roots-rock act (Uncle Lucius, Band of Heathens, Lincoln Durham, Dirty River Boys, etc.) heavily indebted to Hubbard’s signature grit ’n’ groove swamp stomp. For many of them, making the pilgrimage up to “Mount Karma” — the Hubbards’ log cabin shangri-la in Wimberley — to write with the “Wylie Lama” himself is both privilege and right of passage. And if they don’t all come away with keepers good enough for both student and master, a la the Hubbard and Hayes Carll co-write “Drunken Poet’s Dream,” at the very least they’re guaranteed a generous share of sage wisdom, wry wit and, if they’re lucky, a pretty damn good cappuccino (strong coffee remains Hubbard’s last vice of note, though Judy offers that her husband also has a weakness for subtitled kung-fu flicks on Netflix.)

It was over cappuccinos at Mount Karma that Hubbard and I began the first of what turned out to be more than half a dozen different interviews — spread out over the better part of a year — for the Q&A that follows. The conversation started back in February, when Ray Wylie and Judy were still getting the art together for the then freshly mastered The Ruffian’s Misfortune and facing the first round of line edits to an early galley of A Life … Well, Lived. We discussed both at length, but I left with a nagging feeling that we’d barely scratched the surface, so we picked it up again over a couple of days in April and called it a wrap — neither of us apparently having heeded Hubbard’s own warning right there on his album in the ominous opener, “All Loose Things”:

“Right before the harvest a blackbird sings

Look at them fools down there ain’t got no wings

Storm is coming rain’s about to fall

Ain’t no shelter round here for these children at all

Scarecrow singing a song by Kevin Welch

Thunder is rumbling as if the devil himself did belch

Now the dirt is splattering turning into mud

Erasing all traces of broken bones and blood

All loose things end up being washed away …”

The Hubbards’ cabin, high on a hill, was spared the apocalyptic fury of the great Memorial Day Flood of 2015. But many homes — and lives — in the Texas Hill Country were not. Wimberley was hit particularly hard, especially the homes along River Road. “Does it not look like Armageddon?” Judy asked sadly as she and Ray drove me through town for a first-hand look at the damage; weeks of volunteering for clean-up duty had not yet numbed her to the surreal, heartbreaking tableau rolling by outside the car windows. “The water was 42-feet high when it came through here, like a tsunami … Look, see those stilts over there? That’s where that house was that was washed away with those nine people in it … the whole house was taken in full and rushed all the way down the river until it crashed into the bridge and broke apart.”

Within days after the flood, the Hubbards and fellow Wimberley artist Robyn Ludwick set to work organizing a benefit for disaster relief. “This thing was a deep, bloody, horrible wound, and there’s always going to be scars from the memory of it,” Ray conceded, “but we’re going to do what we can to try to heal it, even if it’s just to try to put salve on it.” The all-star “Texas Flood of Love” benefit concert and auction, held Aug. 9 at Austin’s Nutty Brown Cafe, ended up raising a much-needed $120,000 for Wimberley flood victims. But not three months later, Mother Nature pounded the same region again with an encore performance. The Halloween Eve flood wasn’t quite as biblical in magnitude as its Memorial Day predecessor, but for the many still in the early stages of rebuilding their lives and homes — and the friends and neighbors rallying to lend their support and salve — it landed like a sucker punch.

Hubbard’s memoir, released three days after the second flood, was at the printer long before most of the major events of the last 12 months played out. But the loaded ellipses in the book’s title pretty much capture the gist of it. Hubbard nods in agreement when I make this observation at the start of our last interview— more of a debriefing, really — over coffee in San Marcos the week before Thanksgiving.

“A Life … Well, Lived? Yeah,” he says with a light chuckle. “It’s been a very … a very interesting year. And a very busy one, too, even before the floods and the benefit. When the record came out, I told Judy, ‘I want to get out there and work this all over,’ and we really have been all over: I’ve flown so much this year that I’m now on Southwest’s A-List! And the book’s been crazy, too. We just put it out ourselves, you know, which was a real learning experience. I took it to the printer and said, ‘Here’s my book,’ and they went, ‘Where’s your table of contents?’ So, it’s been a process.

“But I’m grateful,” he says with conviction. “I’m thankful for Judy and Lucas. I’m thankful for the people that like what I do enough to keep coming out to see me. And I’m thankful that my hands can still play guitar and that I’m still writing and hopefully, as an old cat, still making valid records.”

And, perhaps it goes without saying, for having a house on a hill?

“Yeah, that too,” he says. “It’s not paid off yet, but it’s still standing.”

* * *

You told me earlier that you had some errands to take care of up in Austin before we could meet today. Just to get a glimpse into what an average day is like for you when you’re not on the road, can you tell me what was on your to-do list?

I went in to give George Reiff a copy of the record, of the CD, to make arrangements for the vinyl. They send two test pressings to him to listen to. What you do is you take the test pressing, and if there’s a pop, you mark where it is, and then you play the other test pressing and if the pop’s at the same place then it’s a manufacturing problem. So we did that. After that, I stopped by South Austin Music and dropped off a 12-string guitar to have a pick-up put in. And then on the way back home, I was going to go by Green Guy Recycling to drop off some stuff, but I was running late and didn’t want to keep you waiting, so I gotta go do that still. And I also gotta run over to Tony Nobles’ place here in town and have him put in a pick-up on another guitar that I’ve got. And then tomorrow I’ve got to do a photo shoot for something or other, and Wednesday I gotta go rehearse with Kyle [Schneider] for Mountain Stage, because I want to be able to do some of the new songs off the record and we really haven’t had a chance to learn them all yet. I think we’ve been doing three or four of them live, but there’s a couple that we need to still rehearse: “All Loose Things” and “Chick Singer,” we haven’t learned those yet.

We’ll come back to the new album, but first off, I just want to state for the record how much I love your book. You’ve made a lot of records over the years, but this is your debut as memoirist, and honestly, it’s terrific. I read it in one sitting.

Well thank you. I read a lot of autobiographies, and I really wanted to make it kind of unique. So I knew it had to have the story of my life — you know, growing up in Oklahoma, moving to Dallas, getting in a band, recording, all that — but I wanted to also put in some of these stream-of-conscious road stories, like the ones I sometimes put on Facebook that people really seem to like. So I’ve got those in there as sort of little mini-chapters, and then we put some of my song lyrics in there, too. And it may not look like it, but I really did spend some time on trying to write it. I kind of went back to the idea where at the end of each chapter, it’s not a punch line, but there’s something where it makes you really want to turn the page.

You gave (music writer/critic) Thom Jurek — who you’ve said coaxed you into doing a book in the first place after you emailed him a couple of those road stories — a “with” credit on the jacket. But it seems pretty clear to me that you wrote this yourself — not just the stream-of-conscious parts, but the narrative chapters, too. It’s apparent just from the pacing and the way you really seem to have fun occasionally using the page as a sort of stage to directly address the reader. This does not read at all like a transcribed-interview-with-stitching kind of memoir.

No. I wrote all of it. But Thom really helped with the capitalization and the punctuation. [Laughs] He said that the stuff I do on Facebook without all of that was really important to have in there, but that a whole book like that would kind of get old. So he said, “Why don’t you go ahead and write it, and I won’t change anything you write, but I’ll capitalize things and put the punctuation in where needed.” So he helped me kind of get it all together. And most of all, his role was really motivational.

When writing about your early years, from childhood all the way through to your 30s and 40s, how connected did you feel with yourself from those different parts of your life? Was there a real distance there, or did it feel like all of that stuff could have happened yesterday? You seem like such a different person today than the character you were in the ’70s and ’80s.

Yeah. I don’t know … but it was interesting, going back and trying to get that perspective from those different times. But the first thing I do remember is that story I tell in the first chapter: hitting my cousin in the head with a rock and then going to church.

You were 5 or 6 years old, and made a pact with God that if your cousin didn’t die from that rock you threw, you would go to church every Sunday for five years.

Right. And I did! Somewhere, I’ve still got those five pins from the Baptist church, for going five years in a row. They’re little pins you’d get every year for going to Sunday School without missing. And I’ve got five of them, and man, they’re somewhere in this house in a box, I think. I was hoping to find them.

You might need those to get past Peter at the Pearly Gates.

Yeah! [Laughs] But anyway, I started talking about that, and I really … there was a lot of going back and writing about the funny stuff, but I remember too all the stuff about like, going to the doctor when my testicles hadn’t dropped, which was just terrifying. And there was always this kind of theme running through it all, which was that thing about these prayers, where I’d pray, but then I’d kind of go back on my part of the bargain. But then later on there’s the whole part about having to accept spirituality again, so it all kind of ties together. That’s really the underlying theme to the whole book: trying to get back to living on spiritual principles today.

And some of the stuff I didn’t really go into detail with. I mention my mom getting killed in the car wreck, and then my dad dying, but as for my first marriage, I didn’t want to really get into any of the sordid details about it. I just didn’t think there needed to be any of that.

How old were you when you lost your mother?

29.

And your lost your father what, about 10 years later?

Yeah.

You write about growing up just being adored by your parents. Did they have many qualms about the route you took? Not necessarily pursuing music, but the lifestyle and habits that you pursued along with it?

Oh, yeah. They never mentioned anything about my drinking or drugging, but I’m sure I worried them a lot, because I don’t think I was very clever in hiding it. And it was kind of a thing too where there was a lot of guilt, because they never got to see me get sober. But they were still …

Supportive?

Yeah. I mean, they’d come to gigs and everything. And they’d let the band rehearse in their living room. The Twinkies would come down and they’d rehearse at their house and they’d stay there. And even after my mom died, and I was doing this other stuff, Terry [”Buffalo” Ware, guitarist] or Dennis [Meehan, aka bassist “Clovis Robilaine”] would come down and stay with my dad. And then later on my dad would run around with [guitar player] Bugs Henderson and all these other guys I knew and play poker with them, but they wouldn’t invite me! Because I was just kind of a bad guy. Like I say in the book, I thought I had this kind of Don Rickles insult humor, but I was really just saying mean things to people. And that was pointed out to me later: “No, you weren’t funny. You weren’t Don Rickles. You were just mean!”

Going back to your childhood, how big was Hugo, Okla.?

I think Hugo was probably about 2,000 maybe at the most — I’m just guessing — and Sopher was population 359. I was born in Hugo and then moved to Sopher, which was 11 miles away. Sopher was where I was raised up. My dad was principal there; grades 1 through 12 were in the same building.

By your teens, your family had moved down to Dallas, where your dad got a new principal job. You write a lot about how your first folk trio, the Coachmen [aka Three Faces West], came together in high school, and how the three of you ended up playing summers out in Red River, N.M. And then you’d all scatter for different colleges in the fall and you started playing with another band back in the Dallas area. But you don’t really talk much about songwriting during those salad days. Were you writing at all back then?

Not really. We were mostly doing Michael Murphey songs. He went to my same high school but was two years older than me, so he was already out in California going to college when we started playing. But he would come back to Dallas and play at the Rubyiat, and we would all go see him and started doing these songs he had. Even when we started playing the Kerrville Folk Festival and the Chequered Flag, we were still doing songs by Michael Murphey and not really writing our own. Well, I guess we had a few. I wrote a song called “Muddy Boggy Banjo Man,” which was on the flipside of a single called “Junk Food Junkie” that my friend Larry Gross did. Larry’s the guy who does Mountain Stage now. Anyway, that “Junk Food Junkie” novelty song he had was a million seller — it was No. 1 for like a week. So we had some originals, but we weren’t doing a lot; it was mostly Michael Murphey songs and some Dylan stuff. I just wasn’t really like a “songwriter,” you know? We were just a folk group.

It’s interesting that you were doing Michael Murphey songs that early on, before the whole “Cosmic Cowboy” era really took off. Bob Livingston once told me that when that scene was in full swing, Murphey was “the Messiah.” Was he like a hero to you all at that time?

He really was. He was a powerful solo entertainer, even before he became the great cowboy entertainer he is now. He had all these incredible songs: “Geronimo’s Cadillac,” “Wildfire,” “West Texas Highway,” and he was just mesmerizing as a solo performer at these little coffeehouses. And he was the only person we knew that did that. We actually knew him; we didn’t know Dylan or Peter, Paul and Mary or the Buffalo Springfield guys, but we knew Murphey. So that was a big deal to know someone who was writing these really incredible songs; it was very inspiring. So yeah, he was quite a hero.

When you say inspiring, was that in the sense of, “If he can do that, I can do that, too”? Or did that level of writing still seem really out of reach?

Well, it wasn’t so much that we wanted to try to write songs like that. But what was inspiring was that our act was playing the same places he was and filling those rooms with great crowds of our own. So it got to where our little act was, I think, at the same level that he was at, at least as performers. We just didn’t have original songs of that caliber.

What was the name of that Dallas area band you played in with Larry Gross in college? In the book you describe it as a jug band, and allude to how it got pretty popular, but I don’t think you ever mention the name.

The Raggedy Sometime Band! I think I recently wrote a Facebook thing about it. So we had this band, and we were playing two sets a night, five nights a week at the Rubyiat, and we were making $250 a week for the whole band. That came to $50 a night split four ways, which was $12.50. Well, we started packing the place, so one night Larry went up to Ron Shipman, who ran the club, and said, “We want a $50 a week raise, up to $300 a week.” Which would mean that each band member would make $15 a night. And the guy goes, “No way, you’re fired!” [Laughs]

Meanwhile, you still had your other little folk scene happening out in Red River. And it was around that same time that “Redneck Mother” was born, right?

Yeah. We had opened our little coffee house, the Outpost, and it was one of those things where we were having a guitar pull, and I think Bob Livingston and maybe B.W. [Stevenson] was there. And the story is, after I went to get the beer and had my encounter at the bar down the street, I came back and just kind of made up “Redneck Mother” on the spot. I had the first verse and the chorus, and all of a sudden Bob starts going, “M is for …,” you know, whatever, and we would spell it out and laugh. And that was about it. But Bob just has a mind where he can remember things, so sometime later when he was playing bass with Jerry Jeff at the Broken Spoke and Jerry broke a string and said, “Bob, sing a song,” he started singing “Redneck Mother.” But just the first verse, the chorus, and spelling out “mother,” because that’s all there was. And everybody went, “what the hell was that?” And then the next night, Jerry said, “do it again!” So one night I got this call from Bob saying, “We’re down here in Luckenbach and we want to cut ‘Redneck Mother,’ but we need a second verse.” I went, “He sure likes to drink Budweiser beer,” because I was drinking a Budweiser, and then, “chase it down with Wild Turkey liquor,” because there was a bottle of that in front of me. Just made it up on the phone. Anyway, they cut it, and that’s Livingston on Viva Terlingua! going, “This song is by Ray Wylie Hubbard.” He just did that because we used to make fun of each other’s middle name. Bob said the record label wanted to take that part off, but Jerry thought it was funny so they left it on there, and so all of a sudden I got a middle name. Before that, I was always just Ray Hubbard.

So what’s Bob’s middle name?

God, I can’t remember now! I guess I should know that, shouldn’t I? [Laughs]

Obviously, it wasn’t just the “Wylie” that stuck. As much fun as you have sort of kicking around “Redneck” as “the obligatory encore” or “the song that wouldn’t die,” what was the immediate impact for you in having that song on that Jerry Jeff record at that time? Was it life changing?

Well, I don’t know if it was full-tilt life changing, because we were already doing OK. Like I say, we were playing the same places as Murphey and Jerry Jeff and filling them up. We’d played Kerrville, the Chequered Flag, the Rubyiat, Mother Blues … all those places. So everybody in this underground scene kind of already knew who I was at the time, which happened to be right when the whole thing was becoming more well known and everybody started getting record deals.

Even your new band, the Cowboy Twinkies. Y’all were signed to Atlantic by Jerry Wexler himself, just like Willie and Doug Sahm. How did that deal end up falling apart?

Well, I was writing by that time: We had “West Texas Dance Band” and “Bordertown Girl” and, ah, I can’t remember the others, but we were playing all of those live and doing really good, and we’d actually cut an album there at Pecan Street in Austin, and it was really a cool. That’s what got us the deal with Jerry Wexler and Atlantic. And I remember we kept trying to say, “Why don’t you just release this? You like it.” But they kept going, “No, we can make it better.” So then we went to Muscle Shoals and butted heads with Bob Johnston, and then came back and never could quite get it together. And later on we did the Twinkies album again for Warner Bros, and they put the back-up singers on it and rope letters on the cover, which was this unfinished thing at the time, and rushed it out. And boy, that broke our hearts. We couldn’t get out and tour behind that record, because we hated it — it just wasn’t us. But the original album we did was a pretty good folk-rock record. It was very, you know, Hearts and Flowers, early Buffalo Springfield, kind of Nashville Skyline sounding; but it just wasn’t going to work for country radio, and that’s what they wanted. So yeah, it was a very weird time. And that’s also when I think cocaine came into the picture, and when I started to, you know … we kept on kind of playing together, and I was still a working musician, but it was all kind of falling apart.

The part of that story that doesn’t make sense is … Bob Johnston was a guy who’d worked with Dylan, Johnny Cash, Simon and Garfunkel. Even all of Michael Martin Murphey’s biggest records at the time. In theory, that would seem like a dream match up for you.

Yeah. It was just strange. Like we’d be doing “Bordertown Girl,” and he’d go, “That’s OK … what else do you got?” And I’d go, “No, we want to put this on the record …” He’d go, “You got anything else?” So then I’d play another one and he’d interrupt me again about halfway through the song. And I said, “Didn’t you hear the record that we did that Jerry Wexler liked enough to give us a deal?” In the end, I guess I just really wasn’t ready to do a record; I just wasn’t at that level yet or something. But it was weird, like we never could communicate very well. I got a chance to make amends with him years later, though. I ran into him over at Poodie’s and we talked about it. I told him, “I don’t know what happened, but I apologize for my behavior.” And he went, “Ah, don’t worry about it — we were just trying to make a hit record. That was a long time ago.”

I know you’ve played with Terry Ware on and off since then, but what about the other Twinkies? Are they all still alive?

No. Jim Herbst, the drummer, died in Florida something like 10 or 15 years ago.

Was there ever talk of a Twinkies reunion, if only just for fun?

Well, we tried one time. I think when I first got sober, maybe ’88, ’89. It was pretty disappointing. Nobody cared! [Laughs] You know, when you’re 21, 22, you can get away with doing “Communication Breakdown” and playing “Silver Wings” and doing the guitar solo like Hendrix with feedback. But when you’re in your 40s, it didn’t seem to work.

After the Twinkies record, you went on to make the album Off the Wall for Willie Nelson’s Mercury imprint, followed by Something About the Night and Caught in the Act — both of which were bankrolled at least in part by drug dealers. It’s actually pretty funny the way you brush over the details of those last two in the book, but you do note that one of those dealers was a fan who just wanted something new from you to play in his car. That sounds like the world’s first Kickstarter campaign.

[Laughs] Yeah, that was Caught in the Act, the live album I did with Bugs Henderson and Mandy Mercier. This guy had just made a big deal and bought himself a Mercedes, and he put in this really good sound system with a cassette player. And he said, “What would it take to get a live recording of you for me to play on this thing, and what would make it sound really good?” I said, “Well, we could get a sound truck …” “How much that cost?” “Oh, probably about $500.” He said, “OK, let’s do it!” And then I said, “Well, for another $700, we could press up some albums.” And he goes, “OK!” and gave me $1,200 cash. So we went and recorded a show at Soap Creek, gave the guy his cassette, he was happy, and we never heard from him again. And then we pressed it up on vinyl and made like, 500 or 1,000 of them. That was the record where I had my hair permed on the cover, because I was going out with a dancer who wanted to be a hair dresser. Oh, and her brother was the drug dealer, so it was perfect!

Do you remember the particulars of the deal with the other drug dealer who helped you make the album before that, Something About the Night?

God, that was a wild story. I actually wrote it up for the book, but it was so confusing, I ended up not using it. The way that one started was, the Gonzos had all recently left Jerry Jeff and were playing with me at the time, but Jerry Jeff called me and said, “I’m doing a live record, why don’t you open for me?” I said, “Won’t that be weird, what with me having the Gonzos and all?” He went, “No, we’re all fine. We’re going to make a live record, and if you want the tape from your part of the show, you can have it.” So we had that, and then we went into a studio and cut some other stuff.

Anyway, we made the record ourselves, and then this guy came along and bought it for $20,000, and he said he was going to really, really promote it. He said, “OK, here’s what we need to do: You call up Willie and get him to do a show, and you can open for him and that way it will be a big release party!” I was like, “No, I’m not going to call and ask Willie to do that.” But the guy kept hammering me, saying, “Well, my partner, he thinks it would be a really good idea.” Well, next thing I know, this other guy calls me and says, “I’m Barney’s partner, and he told me that you got Willie to do a concert for $20,000 that I put up, so I need to see the signed contract.” And I said, “Whoah! What concert? I think we need to talk!” Meanwhile, this Barney guy won’t answer my calls, so my father-in-law attorney at the time, Johnny Crawford, called Barney’s partner and got the story. It turned out this other guy was a drug dealer who’d put up all the money because Barney told him he could get a Willie Nelson concert for $20,000. But Barney had used that money to buy our record — just in order to get me to get Willie — and then his plan I guess was to abscam with the money from the concert pre-sales. Well, Johnny and the drug dealer and I all went over to Barney’s house in Grand Prairie, and that’s when we discovered that he’d picked up and left in the middle of the night. And the drug dealer was like, “Ah, well, fuck …” Johnny and I felt bad for him and wanted to make things right on our end, so we told him, “Well, since it was your $20,000 to begin with, you now own Something About the Night.” And two or three weeks later, the guy ends up getting busted, and Johnny goes, “Tell you what: Give us the rights back to that record, and I’ll represent you.”

So … that was one of my record deals. [Laughs]

These drug dealer guys you’re talking about, what kind of characters were they? Were they scary?

No, not really. They were just long-haired old pot smokers. At that time, you know, in the ’70s …

So they weren’t like “Tuco,” from Breaking Bad.

No, they weren’t like Cartel guys at all. They were just kind of entrepreneurs; you know, like Northern California pot growers. They weren’t shady characters like you see now days. I don’t remember any of them having guns or anything like that, and they all treated me nice; I was a good customer, I guess. It wasn’t until sometime later that it all turned bad and dangerous, when pot and coke turned into freebasing and all that stuff.

Speaking of drugs, you quit all of that at the same time you quite drinking, right? On Nov. 13, 1987?

Yep. Everything. And I quit cigarettes about a year later, and then I quit red meat and pork about a year after that. Still eat chicken and fish and still drink coffee, though.

Do you ever miss any of it?

No, not at all. Because when I drank, I drank for the effect: I liked the way it made me feel. I think I had this illusion where I thought of myself as this drinker who would drink brandy and have a smoking jacket and an Irish Setter, just sitting by a fire … but the truth is, I never had a smoking jacket, I never had an Irish Setter, I never had a fire, and I didn’t drink brandy! I was just a mess. And I’ve really come to realize that if I were to take even one drink now, all of this that I have now would go away. It really would. So no, I don’t miss it at all.

When you count your blessings now, including how far you’ve come artistically over the last 25 years — do you think of all those years before sobriety as wasted time? Or do you think all of that experience was essential to getting you to this point in the first place?

That’s a good question. It’s kind of both. I don’t really relate to that music or what I did back then. A lot of those songs I wrote back then, it’s like somebody else wrote them. But looking back, I think it really was something I had to go through to get to a point to where what I’m doing now really does have value to me. I guess that makes sense in a way.

Even with that disconnect of not being able to relate to them, though, don’t you think some of those early experiences might still inform a lot of the songs you write today?

I would imagine so, yeah. Like I say, I’m embarrassed about a lot of it, about some of my behavior back then, but … and I’m not trying to justify it, but everybody was going crazy back then, doing cocaine in the ’80s and all that. I’m not trying to justify it, but it was definitely a different time back then. And I mean, I had some incredible, great times. We would play at the Lone Star Cafe in New York City on Texas Independence Day with Delbert McClinton and Doug Sahm, and it was just crazy. You look down there in the audience and there’s Robert Duvall and soap opera actors. It was just an incredible time. And we played at the Palomino Club [in Los Angeles] and Col. Tom Parker was at the gig, and so the next day we had lunch with Col. Tom. Another time at the Palomino, we did our sound check and went back to our little hotel to get something to eat, and all of a sudden Jonathan Winters walks in and goes, “How you boys doing?” So we ate dinner with Jonathan Winters and he did this whole routine.

I overheard Judy telling you to be sure to tell me “the story about Willie and the Martians.”

Oh, right. [Laughs] Well, they weren’t really Martians. They were a band called Zolar X that we heard in a bar on the Sunset Strip. We were out there because Willie was playing the Troubadour for the first time, and he had asked if we wanted to open for him. We drove from Houston straight through to L.A., got there a day early, and met this band — they’re still around today, actually. They were like space guys: one guy was dressed all in silver with a silver face and a big old, giant head; another guy was purple and had a lightning bolt; and another was wearing blue sparkle and big old boots. Anyway, we invited them out to the Troubadour the next night, and the show ended up being a pretty big deal: McCartney and Kristofferson were both there, and a bunch of actors and actresses. Well, Willie, Jody Payne and Mickey Raphael all took peyote that afternoon at sound check. Peyote! So of course they’re all still high on it when they’re playing later, and in walks Zolar X — all of them still dressed as space aliens — and they sit down at our table. After the show, we all go upstairs to the dressing room, and I say, “Willie, I want you to meet these friends of mine!” He Willie goes, “Oh, so nice to meet you. Where are y’all from?” And they’re like, “Well, he’s from Saturn …” But the whole time, Willie never even let on that these guys were in costume, because he’s just tripping his brains out. It was a crazy week.

There must have been a lot of those, because that story didn’t even make the book!

Yeah, there’s a lot of them I just sort of forgot about.

You clearly didn’t have any trouble retracing your 12 steps through AA, though. That’s sort of the heart of the book, really; you describe that whole trip almost like Dante moving through the circles of hell. But it was about six or eight months into that journey that you met Judy, right?

Somewhere around there, yeah.

It seems like you were really resisting every step up until then, but after meeting her, it’s almost like you broke out into a sprint.

Yeah. Because the deal was, you know, you’re not supposed to get into a relationship while you’re doing the steps.

She was like your carrot.

Yeah. So I went out and did the ninth step in one weekend. That was a weird thing, going out to make amends, and it was horrible, because I had a bunch of stuff I had to make amends for. God, I can’t remember all of them now, but I went and did them all face to face; said, “I was wrong when I did this, what can I do to make it right?” Then I’d shut up and let them tell me. And most of them went, “great!” But there was one where I think I paid $50 a month for four years to make that particular amend, and on the last check that I wrote when that financial debt was paid, it took everything in the world not to write, “Fuck you!” So really, at that time it wasn’t about getting good; it was just about not drinking. [Laughs]

It wasn’t long after you finished the 12 steps that you started taking fingerpicking lessons. One of the first songs, if not the first song, that you wrote after that was “The Messenger,” which has that line from the poet Rainer Maria Rilke about how “our fears are like dragons, guarding our most precious treasures.” Do you remember your first exposure to Rainer?

It was after I’d been clean and sober for about five or six months. Some girl at some bar gave me that book of his, Letters to a Young Poet. I can’t remember the girl’s name and I can’t remember where it was — might have been Poor David’s Pub — but I’ve still got the book. I don’t think I ever saw her again, but I remember she came up to me and said, “I think you might like this.”

Did it hit you right away?

Well I read it, and it just really started … I still had a lot of doubts about myself, you know. Because when Willie and Waylon and Jerry Jeff all hit, I was too young to be one of those guys, and now Clint Black and Garth Brooks were hitting, and I was too old at 42, 43 to be one of those guys. So I was just kind of really disheartened with what I was doing. But I read that book and that line about fear, and that’s when I decided I needed to learn how to play guitar better. Before that I had always made the excuse that I was too old to start taking guitar lessons, but that helped me overcome my embarrassment. It was right after I read that book that I called that guitar teacher, Sam Swank. And at the same time, I started really studying the craft of lyric writing. I was five or six months sober but still playing at Charlie’s Airport Lounge in between lingerie shows. But I came home one night, was reading that Rilke thing, and all of a sudden decided, OK, I’m going to try to be a real songwriter. I knew I would never be Townes Van Zandt or Guy Clark, but I wanted to write songs that, if I opened for them, I could at least make their audience like me. So that’s when I started writing “Dust of the Chase” and “The Messenger” and “Without Love,” a lot of stuff on that Loco Gringo’s Lament record. I spent about three months just really writing in the mind of that’s where I wanted to be.

When you were writing those songs and wanting to be on that different level, was it just a matter of spending more time on the lyrics than you ever had before?

It was just me deciding, “I’m not going to compromise my songwriting to get a hit, to get somebody to cut it; I’m not going to write it for any other purpose but to write the best song I can about whatever the inspiration happens to be.” And I was doing the fingerpicking thing, too, so it was like all of a sudden, I finally started getting the self esteem I’d been lacking; like with “Dust of the Chase” and “The Messenger” and “Without Love,” I thought, “OK, I think Guy Clark’s audiences will like this.” So I started doing this deal where I would open shows for $50 in front of guys like Arlo Guthrie and Kevin Welch at Poor David’s Pub. Because I needed to let people know that I wasn’t just the “Redneck Mother” guy. And I got a chance to open for Guy Clark in Fort Worth at some really fancy place, like a theater. I think I had Terry Ware come down to play some acoustic guitar with me, and it was just the two of us. And it was so gratifying, because when I walked off, Guy Clark came up to me and said, “That was stunning.” I still remember that. And I just went, “Ah, yes. That was worth it, right there.”

That was the moment.

Well that was the deal: To have someone that I respected so much acknowledge the fact. And then I did a deal with Lucinda Williams and Steve Earle at Rice University, and the same thing happened. That’s where I met Gurf Morlix, who was playing with Lucinda at the time. We did a songwriter thing and it was really cool to be able to do “Dust of the Chase” and to have that audience and to have Steve and Lucinda like that song. It wasn’t like an ego thing, it was a self-esteem thing; it validated all the work that I’d done on learning to fingerpick and really focusing on the lyrics.

1992’s Lost Train of Thought was your first “comeback” album after getting sober, but ’94’s Loco Gringo’s Lament is where your career really rebooted.

Oh yeah. That was the first one I did with Lloyd Maines, and the first record I ever finished that I could hand to someone without having excuses duct-taped to it. We still didn’t really set the world on fire, but we started getting some real nice reviews, and I think it was at that point that we got our first gig at the Cactus Cafe in Austin. And somewhere in there after I got sober I also started playing back at the Kerrville Folk Festival, which was a big deal to me because I hadn’t played at Kerrville for about eight years; my last time there, I played in a blackout. But I got the chance to make amends to Rod Kennedy, asking, “What can I do to make things right?” And he just said, “Come play Kerrville again.”

I take it some burned bridges were a little harder to mend.

[Laughs] Judy kind of found that out when she started doing my booking after we first got married. She called Gruene Hall and got Pat Molack on the phone, and went, “This is Judy, and I’d like to talk to you about booking Ray Wylie Hubbard at Gruene Hall.” Click. He’d hang up. And she called back, and he said, “I’ll never book him again.” She said, “Why?” “He was booked at a gig and he didn’t show up!” So Judy told me, “He said you were booked at a gig and didn’t show up.” I went, “Nah, he’s got me confused with those other three-named guys, like David Allan Coe or Jerry Jeff Walker or Willis Alan Ramsay. It couldn’t possibly be me.” So she called him back and said, “Are you sure?” He said yes. So she came back and said, “He said it was you.” And I went, “Oh yeah … maybe. Oh right! It was that time I was at Willie’s, and I was supposed to play Gruene Hall, but we got kind of loaded and all of a sudden it kind of got late, and I went ‘Uh, Willie, I was supposed to play at Gruene Hall in like 10 minutes, what should I do?’ And Willie took a drag off a joint and said, ‘Well call up Pat and tell him you lied. You’re not going to be there.’ So I called him up and said, ‘Yeah, Pat, I lied, I’m not going to be there.’” I guess he got mad at that, and it was a while before I finally got booked there again. Those last two or three years there before I got sober, I messed up a lot. And it took Judy a while to convince people that …

That this was a new Ray Wylie Hubbard.

Yeah, and that I would show up. It was kind of a struggle there.

Speaking of the “new” Ray Wylie Hubbard, as much as your songwriting and music evolved after you learned to fingerpick, it really changed again after you started playing slide guitar and steering the whole ship into a deeper, meaner groove. That’s sort of been your signature sound now for 15 years. But do you think the fingerpicking folkie in you will ever stage a comeback?

Well, on The Ruffian’s Misfortune, I’ve got “Stone Blind Horses” and “Too Young Ripe,” which are both more in that direction. Especially “Stone Blind Horses,” which to me is very Neil Young folky, it’s more like a Loco Gringo’s vibe. So I never know where I’m going to write now days. I don’t want to just keep the same mid-tempo groove going, and I like trying new things. Like with this record there’s a lot of ’60s garage stuff, too, like “Chick Singer” and “Bad On Fords,” which to me are very, you know, Mouse and the Traps. The way it always works is, I kind of write the songs first and then see how the record turns out. But … I did convince Judy that I needed a 12-string, so I’ve started playing and writing a lot on that. I’ve got some new songs that actually have melodies and a lot of chord changes, instead of just, you know, staying in E or only having two or three chords.

George Reiff pointed out to me that a lot of the songs on Ruffian’s Misfortune are actually one-chord songs. Which, he noted, presented a real challenge for him as a producer. But he thinks y’all pulled it off.

Oh yeah. Like I say, the first … listen to that old R.L. Burnside and T Model Ford stuff — those guys, they just got a groove. But you try to keep it interesting. “Too Young Ripe” is just one open chord except for the very end, where we put a little 4 in there. You don’t really hear it, but it just kind of insinuates it to let you know it ends it. So yeah, I get that groove, and to answer your question … I’m not a full-tilt blues guy, I’m not a folk purist, I’m not a rock ‘n’ roll singer and I’m not a country guy, but I’ve been influenced by all of those. So I just kind of never know … I got up this morning and got that 12-string and started playing “There Are Some Days” and started thinking, “I need to start doing this again, need to start playing 12-string and maybe mandolin, just to kind of get back in there, throw it in, see how it works.”

Whatever kind of guitar you’re playing, one thing that seems to have remained consistent going all the way back to Loco Gringo’s is the quality and craftsmanship of your lyrics. And I think that’s really apparent with all of the songs you included in the book: the lyrics really hold up on their own and in some cases the poetry comes across even better on the page. And then there’s songs like “Rabbit,” where the groove is so deeply ingrained, you can practically read it in every line. Speaking of, my all time favorite line of yours is still, “I said to the rabbit, ‘are you gonna make it?’ The rabbit said, ‘well, I’ve got to!’”

[Laughs] Well, that’s actually from an Ace Reed cartoon. When I was going through my dad’s trunk after he died, there was a little picture frame with a cartoon in it by this guy named Ace Reed. He was a cowboy cartoonist who did these things called “Cow Pokes” that ran in a horseman magazine, True West. And the first frame in this cartoon showed this old cowboy sitting on a fence and this dog is chasing this rabbit, and the caption goes, “Are you gonna make it?” And the next frame the rabbit looks up and goes, “Well I’ve got to.” And I found that and it just hit me, for some reason, why my dad would cut this out and even put it in a little tin 15-cent frame and keep it in this trunk forever. And then I remembered all these times when we’d be driving somewhere, and I’d say “Are we gonna make it?” And he’d say, “Well, we got to.” And I put the two together and just thought, wow. So I put that line in there and it still means a lot to me. “Are you got to make it?” “I’ve got to! If I don’t, what are the consequences?”

Let me ask you about a couple of other songs while we’re at it. Starting with “Snake Farm.”

I’d been reading Flannery O’Connor, and one of her quotes is, never second-guess inspiration. The idea is, when you get inspiration, never doubt that and go “that’s no good.” So I was driving down I-35 past that Snake Farm one day, which of course I’d probably driven by 10,000 times before, but that day I just went, “God, that just sounds nasty.” Then I said, “Well it is, it’s a reptile house, it’s not a hospital.” And I went, “Ewwwww … Snake Farm, it just sounds nasty … Snake Farm!”

Just talking to yourself?

Yeah! By myself, there was nobody there with me. And I thought, “Wow, that’s kind of catchy.” Then I went, “Nah.” But then I remembered that line about never second-guessing inspiration, and was like, “That’s it! That’s what she meant!” After that, it was just, ok, what the hell do I do with it? I’ll make it a love song about a man who doesn’t like snakes, but he’s in love with a woman who works at the Snake Farm. What kind of woman would work at a Snake Farm? Well, her name would be Ramona, she’d dance like little Egypt, she’d drink malt liquor … All the lines and verses just came together, until I had to go to a rhyming dictionary to look up something that rhymed with farm, and it was “alarm.” And I went, “The Alarm! She would like the Alarm!” [Laughs]

“Conversation with the Devil”?

Somebody had given me the Divine Comedy. So I was reading that, and then I started reading about the history of it, about how Dante used the image of going to hell to say political and kind of anti-religious things. And I thought, wow … if you use that set-up that you’re in a dream, you could say whatever you want to say. So I had that in mind, and later I was having coffee with Stephen Bruton up in Austin, and we got to talking about things that weren’t appreciated. And we both agreed that the devil’s fiddle solo in the Charlie Daniels song was actually a better solo, and that the kid was showing off. Then a couple of days later, I heard Judy talking on the phone to I think some girl that she sponsored for AA, and she said, “Well, some get spiritual because they see the light, some get spiritual in jail cuz they feel the heat.” I went, “Ah!’” And then a couple of nights later, I was reading the Divine Comedy again, and fell asleep thinking about our son Lucas, who was about 3 or 4 at the time. When I woke up, the whole song just came together in about an hour.

I’ll tell you a funny little story about recording that song with Lloyd Maines for the Crusades of the Restless Knights album. We had cut “Conversation with the Devil” with a full band: Stephen Bruton on guitar, Paul Pearcy on drums, Glenn Fukunaga on bass, and I can’t remember who the keyboard was, but man, it was rock, like “Positively 4th Street” electric Dylan. And it was really good, too. But after the rest of the record was done, I kept coming back to that song and all of a sudden I realized, it wasn’t a Dylan song, it was a Woody Guthrie song. The music was great, but the lyrics were getting lost. So I called up Lloyd and said, “Lloyd, I love the record, except ‘Conversation with the Devil’: it’s not Dylan, it’s Woody!” And he goes, “You’re right! You’re right!” I said, “I’d really like to recut it with just acoustic guitars.” He said, ‘OK, let’s do it! How about 1 o’clock tomorrow?” So we go to Cedar Creek and I play it for him on my acoustic guitar, and he goes, “Oh, that’s going to be great!” I said, “Well, get your acoustic guitar, so we can get some little fills in there.” He goes, “I don’t have one with me — I thought you wanted it to be just you.” I went, “No, I meant guitars — there was an ’s’ on there, two acoustic guitars.” Well luckily the studio had one there — just this old, gnarly cage, really — so we set up across from each other and we did it one time. And he said, “That’s pretty good, let’s do it one more.” So we did it again, then played them back, and he goes, “That’s great! That second one’s great!” I went, “Well I kind of rushed the words right there a little bit, and here you did that lick but later on you didn’t …” He said, “Na, it’s great!” I said, “Well, right there you can kind of hear my throat catching a little bit …” He went, “No no, use it!” Finally I said, “Lloyd, you gotta catch a plane?” And he goes, “Uh, yeah as a matter of fact I do!” [Laughs]

But, Lloyd was really instrumental in teaching me about the studio. The first record I did with him, Loco Gringo’s, was the first time I’d been in a studio where I was really aware of what was going on and started to understand what the producer’s role was. He was brilliant at that. And so was Gurf, when I started making records with him. And both those guys also really helped boost my confidence in my guitar playing. I was never really that self-assured about my playing before, but Lloyd and Gurf would both say, “You play the lead!”

One more song, artist’s choice. What’s the signature song for you on The Ruffian’s Misfortune?

“Stone Blind Horses.” That’s the last one on the record, and the last one in the book, because that’s kind of where I am today. As I’ve gotten older I’ve really started thinking a lot about mortality and God and about how a lot of my friends are dying. And I kind of look back and somehow keep thinking of that image or idea of “riding stone blind horses, never seen a reason to believe.” Because you know, that’s kind of where I was the whole time in my 20s and 30s: I didn’t see a reason or a need to believe, I didn’t need any of that. But as I’ve gotten older, I’m like, “Well, I hope God grades on a curve!” [Laughs] If you’ve got Attilla the Hun on this end and Mother Theresa on the other, hopefully I’m somewhere here. And that line came to me about, “There are some saints that have been forgotten.” So I got on the computer one night and typed in “saints” and it came back with a whole bunch of them that I’d never heard of. So the line became, “There are some saints that have been forgotten, like most of my drunken prayers.” And for some reason I also looked up “redwing blackbird” and started reading about how the Navajo believe that the slurred whistle that the blackbird makes sounds like the words “that I might die.” Whoah! So, you know, “the high-slurred whistle of the redwing blackbird sounds like he’s singing ‘that I might die’” — it may not make a lot of sense, but it’s based on fact: Nobody can mess with me on that, because I can say, “Look right there, the Indians say that’s what it is!”

Can you describe the feeling you get when you finish a song that you’re really proud of? Or do you have any kind of ritual, or way that you kind of reward yourself when you know you’ve done good?

Well, I say thanks. I still do that. If I finish the song and I play it and then I play it again, I always say “Thanks.” The same thing with the guitar … when Tony Nobles made me a guitar, I went out into the woods and played it for the other trees. [Laughs] I said, “Here, this is your brother!”

Really?

Yeah! I just went out by myself to these trees and played the guitar for them, to just give an acknowledgement of something, somewhere. So anyway, after I finish a song, I’ll go, “thanks,” and then I’ll go, “Yeah, this is going to work. This is really going to work.” Like with “Stone Blind Horses,” I said, “This works. This is going to close out the record.” And sometimes, too, I try not to think about the recording, but all of a sudden like with “Coricidin Bottle” on The Grifter’s Hymnal, it was like, “Bam! That’s how I’m gonna open the record.” And when I wrote “All Loose Things,” once I hit that chord, I knew that was going to open this record. Because that’s the way to open a record!

Of course, when you wrote and recorded that song, you had no idea how prophetic it would turn out to be.

Yeah, it really was. “All loose things get washed away.”

Were you thinking of a literal flood when you wrote it, or was just the imagery?

I think it was just the imagery of it … and just the whole idea of the black bird flying up above, going, “Look at them fools down there, they ain’t got wings. Storm’s coming! You better hold onto something.” Whether the flood’s a metaphor for something or not, you better have something to hold onto or you’re going to get washed away. You’re gonna get swept up in horrible headlines or something. And I’ve always liked the idea of having blackbirds and other little critters saying profound things, like in Aesop’s Fables or Animal Farm. I like the mythology or the nursery rhyme idea of it. Sometimes it also makes me think of Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire, where you’ve got this funky guy in a torn T-shirt, but his words are from Tennessee Williams.

So, what’s ahead on your horizon? Have you started thinking about the next record yet?

Oh, I’ve got a bunch of songs that I’m working on that are almost ready to go. But putting out a record and a book in the same year was really pretty crazy, so I don’t know how soon the next one might be. We might record next year to come out the year after that.

But haven’t you also been working on a record where you’re re-cutting a lot of the songs that you originally did for your albums on Rounder in the ’90s?

Oh yeah, well we’ve got that one almost done, actually. I’ve just got to go back in and re-sing one song. Most of the songs were originally from the Rounder records, but I also cut “Screw You We’re From Texas” and “Wanna Rock and Roll” with Bright Light Social Hour, and man, they really rock — I mean, it’s just a completely different ballpark than I’ve ever been in before. Anyway, we’ll probably mix that one coming up real soon that and put it out next year.

You have a title for it yet?

I think it’s going to be called The Shroud of Touring. [Laughs]

Actually, that kind of sounds like more of a live album, though, doesn’t it?

Yeah.

Well, tell Judy.

Great article, reading his book now. Love it !

Great story about a special man. We love RWH.

The Brando film is “A Streetcar Named Desire”, a ride we’ve ALL been on before. Thanks for bringin’ it, Ray.

Thanks for a great article! This was by far the best interview with Ray I’ve ever read.

Love that “Badass Rockin RWH”. been

on your journey for about 35 years

do you remember coming to Combine

for Rick’s 40th surprise birthday party on his 39th b-day – so the next year he could be 39 forever. You said you might have to leave anytime as Judy was about to have Lucas – what a wonderful son who is a badass guitar player too!!

Can’t wait to read your book, but feel this article told most of the story. Keep working and build that “Wimberly City Limits” venue it will blow ACC out of the water!!!! Love you brother!!! Pam & Rick

Nelms – Dallas

[…] LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, Dec. 10, […]