Notes From the Editor

By Richard Skanse

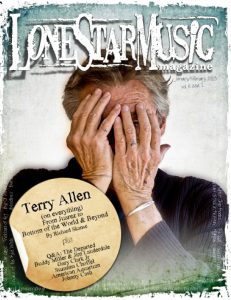

(LSM Jan/Feb 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 1)

Thank you for picking up our latest issue of Lone Star Music Magazine. We’ve been mighty busy since the last one, what with the holidays and launching our brand new record store in San Marcos, Superfly’s Lone Star Music Emporium. But somehow in between all the shopping and celebrating and sorting through literally thousands upon thousands of pieces of used vinyl, we managed to knock out what I think is one of my favorite issues to date. Inside, you’ll find features and Q&As on the varied likes of the Departed, Buddy Miller and Jim Lauderdale, North Carolina Americana rockers American Aquarium, Texas’ latest Voice contestant, Suzanna Choffel, and the inspiring efforts of Dustin Welch and other Texas songwriters to help veterans express themselves through music via the Soldier Songs & Voices program. Back in reviews, we spin the latest by Kelly Willis and Bruce Robison, Kris Kristofferson, and Gary Clark Jr., arguably the hottest national contender to spring out of Austin since, oh, Stevie Ray Vaughan. And if you’re a Johnny Cash fan, has Mr. Record Man ever got a treat for you: an in-depth review of the Man in Black’s 63-disc Complete Columbia Album Collection box set. And in our columns department, Terri Hendrix reflects on her lifelong passion for collecting (and making) music, Javi Garcia waxes poetic on the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers, new contributor Holly Gleason (“Rowed Over”) offers a Music Row-insider’s take on TV’s Nashville, and Rita Ballou hands out her first ever “Velvet Koozie Awards.”

Oh, and then there’s our little cover story on Terry Allen, which happens to be the longest piece I’ve ever written outside of the unpublished novel I’ve been chipping away at for the last 20 years. I’m a tad too embarrassed to admit the actual word count, but if any Artist (capital “A” intentional) we’ve ever covered — or that I’ve ever interviewed in the last two decades — deserves the Peter Jackson-esque epic treatment, it’s this guy. And not just because his new album, Bottom of the World (his first in 13 years) already has a guaranteed spot on my Best of 2013 list.

The first time I interviewed Allen was back in 1999, right after he’d released his last album, Salivation. I had only been familiar with his music for a couple of years at the time, having started with 1996’s Human Remains on the recommendation of a dear friend and quickly working all the way back to his 1975 debut, Juarez — hands down, still one of my all-time favorite albums. But as highly as I regarded his music — ranking his songcraft right up there alongside Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt — I knew next to nothing about the rest of Allen’s art, apart from whatever passing reference his label bio made on the subject. I vividly remember trying to wrap my head around his description of “Countree Music,” a piece he’d recently finished for the Houston airport that incorporated a floor map of the world with a big tree stuck in the middle with branches that reached out across the map. In each branch was a speaker playing music (by Allen and friends Joe Ely and David Byrne) representing different countries, so that one could circle the map and hear sounds from around the world. Then Allen told me about the customized cattle brands he’d been making, like the spiral reading “All artists trying to be God will burn in hell” and one with the word “Control” at the end of a deliberately unwieldy 12-foot pole. “For a flat fee I’ll come and brand your wall or I’ll brand your car or I’ll brand your carpet,” he explained, proudly noting that he’d just branded half of Ely’s house with “Irony.” “We nearly burned down his studio door because the paint caught on fire — but it looked great after we put it out.”

All things considered, I thought it went well — but I walked away from it feeling as mentally exhausted as I had after the only other interview I’ve ever done with a subject whose art and intellect flat-out intimidated the hell out of me: Warren Zevon (RIP). Trying to keep up with both of them was about as unnerving as playing chess against a Garry Kasparov.

A few years later, I ended up renting an upstairs apartment in the Buda, Texas house owned by Allen’s oldest son, musician and songwriter Bukka Allen. In the hallway downstairs was a series of framed, original Terry Allen artwork — pieces that mystified me on a daily basis me even after I started getting accustomed to seeing Terry and his wife, actress/writer Jo Harvey Allen, whenever they’d swing through town for work or visits. But apart from casual pleasantries and occasionally asking Terry what he was working on, I kept what I hoped was a respectful distance; about the longest I talked with Allen during my two years as his son’s tenant and roommate was to grab an anecdote for a feature I was writing on Ely. At the time, Allen was in the midst of staging an ambitious multi-media art and theater piece called Ghost Ship Rodez, but I figured I’d wait until he finished an album of new songs before tackling the subject of his own art again. Truth be told, as eager I was to hear the follow-up to Salivation, the thought of really interviewing the guy still kinda freaked me out.

Fast-forward to the fall of 2012, and it still freaked me out, especially as I frantically reviewed my notes and questions on the flight to Albuquerque and crammed in one more good listen to Bottom of the World in my rental car en route to his house in Santa Fe. Much to my relief, though, the ensuing interviews — both one-on-one with Allen in his studio and with Allen and his wife over a couple of very pleasant meals out on the town — turned out to be some of the most enjoyable I’ve ever done. They were candid, funny, and full of insight into the demon work ethic and vision that goes into making art that consistently challenges convention and never fails to fascinate, whether it be in the form of sculpture, theater, or song. For years, I made the common mistake of pegging Allen as a world-class Texas songwriter who also “did” art, or vice versa. Now I know better. In Terry Allen’s world, art is art, period — and few people walking the earth today are creating it in any way, shape or form quite as masterfully as he is.

No Comment