By Don McLeese

“It’s the singer, not the song.”

— Mick Jagger/Keith Richards

“I’m just an old chunk of coal

But I’m gonna be a diamond someday.”

— Billy Joe Shaver

Everybody’s a critic. If you’ve been participating in Lone Star Music’s “That ’70s Texas Progressive Country/Honky-Tonk Heroes Shotgun Showdown” tournament poll over the past few weeks (and if you haven’t, you’ve been missing a whole lot of fun), you’ve been exercising your critical faculties, or at least knee-jerking your opinions, with every point and click.

Every time you’ve decided that the rough-hewn propulsion of this album trumps the more polished production of that one, or that it’s more important that a singer-songwriter writes better than sings better, or that the historical significance of this album is more crucial than the commercial success of that one, you’re making a critical value judgment, an argument.

And the beauty of the process is, there are no right and wrong opinions. But, if you’re a reflective type who wants to ponder the thought processes behind those opinions, there are stronger and weaker arguments. It all comes down to what am I really saying when I’m saying this is better than that?

Some of the choices have been tough from the start, and they’ve gotten tougher as you’ve winnowed the field, from 64 to 32 to 16 to 8. But I never expected to face a choice as complicated and difficult — even impossible, at first glance — as this one presented in Round 3:

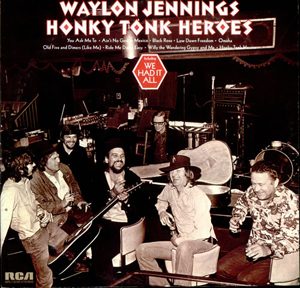

Honky Tonk Heroes by Waylon Jennings

vs.

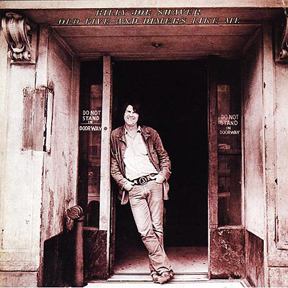

Old Five and Dimers Like Me by Billy Joe Shaver

Was this luck of the draw or the scheme of a diabolical bracket maker? Both were released in 1973, both are seminal works of the “Outlaw Country” surge to come, and both sounded even stronger when I recently revisited them than they had in memory.

But, here’s the rub: The Waylon album could not possibly exist without the songwriting of Billy Joe Shaver, and the Shaver album (and perhaps his recording career) would not have happened without the Waylon classic.

How could there be one without the other?

Which is better: The chicken or the egg?

To clarify that analogy without beating the poultry into the ground, Shaver’s songwriting is the egg, and Jennings’ album is the chicken. Shaver’s debut album finds him still in his formative stages as a recording artist, his songs strong and their vision singular, but no one would mistake him for a professional, experienced singer. His vocal range is narrow, his phrasing hit-and-miss. It’s a voice that lurches here, wobbles there. He’s plainly trying to find his comfort level in the recording studio, and with the arrangements and band accompaniment that had never been part of his songwriting process.

It wouldn’t be smart to call Waylon a chicken, but his album is fully hatched, with an artist who has fully mastered vocal nuance and subtlety (and had yet to succumb to the cliché and caricature that would be his “Outlaw” baggage) delivering perhaps his best album to date, an album that would be a turning point in his career and in the progressive country movement. It is a stronger and more cohesive song cycle than Jennings could have written himself, or than most of his celebrated peers could have. Those songs signal something radically fresh and new and raw and honest in country music.

Nine of those 10 songs are Billy Joe Shaver’s. The first two songs on Shaver’s Old Five and Dimers are also highlights of Waylon’s album, and the title song (of Shaver’s) holds the pivotal second slot on each. In retrospect, I’m surprised that only three songs are duplicated, though one of the necessities of Shaver’s album was to show that there was more to him than what they’d already heard on Waylon’s Honky Tonk Heroes. Because, at the time, pretty much everyone who bought Shaver’s album had been introduced to his name by Waylon. Shaver wouldn’t have had an album — at least not this one, this quick — if it weren’t for Waylon’s album.

So how did a major country star such as Waylon end up devoting almost all of one of his best and most significant albums to the promotion of a previously unknown songwriter such as Billy Joe? And how did Billy Joe employ that calling card as the springboard for a career that continues to this day?

It’s a story that’s very much of a specific time and place, the same time and place celebrated by this whole “Shotgun Showdown” exercise. And it’s a story that has to be considered apocryphally, given the addled, inebriated minds that spawned the memories of that time and place.

But, first, a little context: The early ’70s were a musical era when the previously rigid wall between country and rock, and between rednecks and hippies, started to crumble — particularly in Texas. And most specifically in Austin at the Armadillo. The music industry at large had started to take notice, with Willie Nelson re-launched on a new label with a new freedom, and Sir Douglas Sahm forsaking the psychedelic flashbacks of the ’60s to return home as a roots-rocking solo artist. Jerry Jeff Walker, who had mainly been known for “Mr. Bojangles,” had also reinvented himself in Texas as the original Lost Gonzo.

So, call it Lost Gonzo, Redneck Rock, Cosmic Cowboy, or, still to come, “Outlaw Music,” there was a new freedom in the air, a lot of dope and maybe some of that hippie free love. And Waylon wanted some of it, particularly now that his RCA contract had expired and he was being courted by Atlantic, the same label that had corralled both his buddy Willie and Doug Sahm.

Though he ended up resigning with RCA, he had negotiated for the freedom that Willie had, the freedom to record whatever he wanted with his own musicians, rather than processing his music through the Nashville pipeline. As the apocrypha goes, at a Dripping Springs gathering in 1972, he heard a song that really struck him, titled “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me,” by a guy who was missing a couple of fingers and perhaps a few of his marbles.

“It’s my song,” responded the unknown Billy Joe Shaver, who proceeded to play him some more. A likely inebriated Waylon promised to cut a whole album of the roughneck’s songs if he made it to Nashville. Billy Joe took him seriously, made the trip, and discovered that Waylon had no intention of making good. Maybe he didn’t even remember the guy, or the songs, or the promise. He offered Billy Joe a hundred bucks to go away. In response, Billy Joe offered to kick his ass.

So, Billy Joe played him “Willy” (again), and Waylon loved it (again). And Billy Joe played him some more (again), and Waylon loved those as well, and (again) agreed to devote his next album to the songs of Billy Joe Shaver. RCA country honcho Chet Atkins was aghast, but the label had granted Waylon full freedom and he was exercising it (though RCA would subsequently delay the release).

Co-produced by Jennings, stripped down in instrumentation and filled with the plain-spoken poetry of the unvarnished, unknown Billy Joe Shaver, Honky Tonk Heroes was like an Emancipation Proclamation for the Outlaw Music to come, introducing a new spirit, a new ethos and a new songwriter who was a force to be reckoned with. Billy Joe wrote most of the material on his own, while one of the best, “You Asked Me To,” was credited as a Shaver-Jennings co-write.

Only the final number carried a different imprint, as “We Had It All” would become a popular standard. It was a ballad (with strings) written by Troy Seals and Donnie Fritts. The latter was a songwriter in the Dan Penn vein, who also played keyboards in the band of Kris Kristofferson, who would soon be credited with production on the debut album by … Billy Joe Shaver, who had landed his own deal on the strength of his songs as recorded by others, Waylon foremost among them (though even Tom T. Hall covered “Old Five and Dimers” during that pivotal year). This was common practice at the time, as songwriters such as Guy Clark and Ray Wylie Hubbard found themselves with deals as recording artists after Jerry Jeff Walker had turned their songs into anthems.

Old Five and Dimers remains an auspicious debut, and a more accomplished one than I had remembered, though it lacks the cohesion and consistency that made Waylon’s album a masterpiece. It showcases a more eclectic Shaver, featuring the strong streak of Christian faith in his material that Waylon had bypassed (and which would occasionally become a little belligerent in Shaver’s music to come). The arrangements have a ragtime, Dixie feel to them, and the vocals show a new voice who is not only unpolished, but un-sanded. And it has “Georgia on a Fast Train,” so autobiographical that Waylon had wisely avoided it.

When this match-up was introduced in Round 3 of the Lone Star Music bracket, it was a ridiculous challenge — these two albums that had such synergistic significance that it seemed impossible to separate their breakthrough achievements.

Waylon had taken the raw material of Shaver’s songwriting and crafted it into something extraordinary, without sacrificing any of its powerful transparency to studio polish. These were very personal songs, and Billy Joe was the person who wrote them, but Waylon inhabited them like a great actor with a great role, a role he would continue to define and expand, a role that would eventually define him.

Yet it was an album that wouldn’t, couldn’t exist without the singular songwriting of Billy Joe Shaver, one of the freshest visions to emerge from the new freedom for Texas country music in the 1970s. Waylon was waving that flag, but Billy Joe had designed it (at least this particular version).

As I learned when I was in the midst of writing this, the people have spoken, and though the margin was slim, Old Five and Dimers has triumphed over Honky Tonk Heroes, an outcome that would have been unthinkable four decades ago, when Waylon’s album had kicked opened the doors in Nashville through which the renegade Outlaw Music would stampede. Partly because of the label issues that would plague him throughout his career, Billy Joe’s debut seemed so negligible at the time within the music world at large that he wouldn’t release a follow-up for three years. So picking the latter in hindsight over the former seems to me like something of a Lifetime Achievement Award for Billy Joe, along with a sign that perhaps Waylon’s legacy hasn’t aged as well as that of some of his contemporaries.

But in the obligatory Googling involved in a piece like this, I came across a couple of quotes that might provide some needed perspective. In Michael Striessguth’s Outlaw book, Waylon’s drummer Richie Albright remembered recording the scene-setting title song, which starts slow, stripped-down and intimate and then pushes forward after it has pulled you in:

“We were doing the album and Billy Joe was around, and we began ‘Honky-Tonk Heroes,’ so we cut the first part of the song and we stopped, and Waylon said, ‘This is the way we’re going to do it.’ And Billy Joe had been sitting in the back and he comes walking up, saying, ‘What are you doing? You’re fucking up my song. That ain’t the way it goes.’ Pretty soon Waylon and Billy Joe are just hollering at one another. Billy Joe didn’t understand the way we were putting it together … then we put it together and he said, ‘Yeah. That’s good. That’s the way it goes.’”

Or, as Billy Joe told NPR decades later, “The songs were so big, they were too big for me. I couldn’t possibly get them across the way [Waylon] could.”

In other words, Waylon Jennings showed Billy Joe Shaver how and where Billy Joe’s songs could go. And that’s the difference between a recording artist and a songwriter. I could be wrong, but even after all these years, Billy Joe himself might have voted for Honky Tonk Heroes. Like I did.

[Editor’s Note: Shaver’s Old Five and Dimers Like Me beat Jennings’ Honky Tonk Heroes by a margin of 55.2% to 44.8% in Round 3 of our “Shotgun Showdown,” advancing to Round 4 for a matchup against Townes Van Zandt’s Flyin’ Shoes. Jennings advanced to Round 4, too, albeit with his 1973 album Lonesome, On’ry & Mean (now facing Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger). Voting for Round 4 ends Thursday at 5 p.m. CST.]

I voted for Honk Tonk Heroes too. Billy Joe has alway been the lose cannon on the deck with Waylon our Blackbeard!