By Holly Gleason

“My definition of country music is — in so many words — sheer beauty delivered with ugly honesty,” begins Maren Morris, trying to anchor something every good Texas girl should know. “There’s nothing that couldn’t be said in a few words. It was rooted in that from the very beginning.

“There’s something in country music that always pushes the encyclopedia of life,” she continues. “Hank Williams and Johnny Cash being excommunicated, Merle Haggard and Loretta Lynn writing ‘The Pill.’ All these scandalizing real things …”

After three years as a songwriter, the Arlington, Texan has already mined a gold single with her very first major-label release, the genre blurring, but roots-driven “My Church,” earthy and country, but with a heavy soul/gospel underpinning. The song of swearing some, cheating a bit and falling from grace offers redemption on the FM dial, open road as altar with absolution one record away.

“When Hank brings the sermon

And Cash leads the choir

It gets my cold coal heart burning

Hotter than a ring of fire

When this wonderful world gets heavy

And I need to find my escape

I just keep the wheels rolling, radio scrolling

Until my sins wash away…”

Morris doesn’t sound like Patsy, Tammy, Dolly or Loretta, but like her forebears, she’s trying to be honest about who she is, where she fits and how she sees it. She explains, “I feel like what I was missing on the radio, at least for me, was a song that I’d lived. I’m not talking about falling in love or seeing a cute guy; I don’t wanna harp on that lovey-dovey stereotype stuff. I’m not a super-duper teenybopper, and I’m not worried about all that.

“I’m 26 years old. I’m not married, and I don’t wanna be right now,” she continues. “I feel like so many people of my generation feel the same way. I don’t wanna feed the stereotypes or play to what someone thinks I should singing about.”

It’s not defiance, even if the words would incite a post-Dixie Chicks quiver in the hearts of the conveyor belt mainstream country industry. Morris, who came to town to visit Kacey Musgraves, followed her to her publishing company and stayed to be a songwriter has spent a fair amount time riding the outer edges and watching the deals go down.

Though she’d already released three indie records, she had no intention on chasing the fame. Too compromising, too many things to take her away from the thing she loved: being creative. But time — and watching artists who just don’t quite bring it — was enough to lure the young lady back into the spotlight.

“It was a conscious decision,” she confesses with a reluctant laugh. “I had a sense of what I was signing up for, and I knew I would be less on the creative side than I was used to: being in a room five days a week, making up songs. But I missed being onstage so much and having that connection with the fans.”

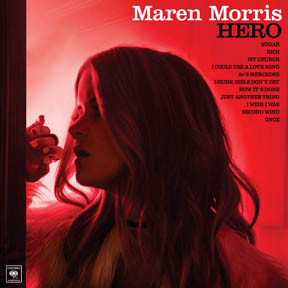

Beyond the immediacy of that connection, it also allowed Morris to write songs from the purest perspective: her own. In the way Hero balances the wry misdirection of “Drunk Girls Don’t Cry” with the lo-fi ambience of the subtle seduction “This Is How It’s Done” and the wah-wah slink of the high-hat and quickening vocal of the non-commital “I Wish I Was,” it’s obvious the streetwise songstress is a hands-in-pocket sort of pragmatist.

Beyond the immediacy of that connection, it also allowed Morris to write songs from the purest perspective: her own. In the way Hero balances the wry misdirection of “Drunk Girls Don’t Cry” with the lo-fi ambience of the subtle seduction “This Is How It’s Done” and the wah-wah slink of the high-hat and quickening vocal of the non-commital “I Wish I Was,” it’s obvious the streetwise songstress is a hands-in-pocket sort of pragmatist.

Working with the unlikely pop hybridizer busbee — who’s worked with Shakira, Adam Lambert, Christina Aguilera, Daughtery and Gavin DeGraw, as well as Keith Urban, Lady Antebellum and Lauren Alaina — the pair incorporated attenuated phrasing, syncopated lines scattered amongst straight vocalizing, creeping arrangements that swoop from lean to lush and some of the most musical melodies on country radio now. If there is rhythm and blues, a waft of EDM, a bit of post-disco calypso, a slightly dubstep, Rihanna-evoking “Sugar” and even the neo-ska undertow of “Rich,” the unifying element is Morris’ slightly nasal, almost affectless alto.

Even when she’s going for it, she never throws herself down the stairs in some kind of overpowering melismatic moment. With “Second Wind,” a post-modern survivor realm, her voice climbs and flexes, matching little trills with a power chorus that pushes back with gusto. When her voice rises, sweeping the declaration “you can hate me, but don’t underestimate me/do what you do ‘cause what you do don’t even phase me…” into the heavens, it’s obvious Ms. Morris ain’t playing.

The dark haired sensation realizes part of what allows her to mix and match is her own vast listening habits. “When busbee and I wrote ‘My Church,’ we were listening to a lot of early Sheryl Crow. It’s funny — we didn’t re-record anything, not even the vocals. Sonically Tuesday Night Music Club really influenced us: the drum sounds, blending gospel, and rock ’n’ roll, and pop, then rootsy country. You don’t think about it, you just draw what you need — and let what’s there happen.”

She pauses, collecting her thoughts, her motivations. Turning her intention slightly, she continues, “I never want to be pigeon-holed. I want to really, really stretch myself — especially because I have to sing these songs every night.”

And singing these songs every night is the bottom line. With a coveted slot on Keith Urban’s Ripchord Tour, Morris is taking her songs to some of country-pop’s most discerning fans. Though she’d only put out her self-titled EP on Sony Nashville, the buzz was so deafening, her ‘90s retro-fit pop-country made her a logical choice for Urban’s tour. In part, Urban’s decision to invite her out on the road is the direct result of Morris’ singularity. Like her friend Musgraves or fellow Texan Miranda Lambert, no one would ever confuse Morris with any of the herd of glitter Barbies yearning to be the next Carrie Underwood.

“My publisher used to tell me, ‘There’s so much of you in here, I couldn’t imagine pitching this to someone else,’” says Morris. “They meant it as a compliment, but I wanted that validation of having artists record (my songs). As a writer, you’re this team player, so you’re writing for someone else’s perspective. You can insert your own truth, but because it’s making it palatable for someone else to be in, you water yourself down. But I can’t water down.”

All she had to do was get back to making records. If she thought songwriting for others was a great way to make a living — and when your co-writers are hitmakers Barry Dean, Shane McAnally and Natalie Hemby, the living is good — the integrity of her voice eventually won out.

“I needed some time to figure out my truth,” she says. “And then the record fell out. It really is this hodgepodge record; all my influences are all there. This grew out of a collection of demos, and it’s all over, but it’s also just who I am.”

No Comment