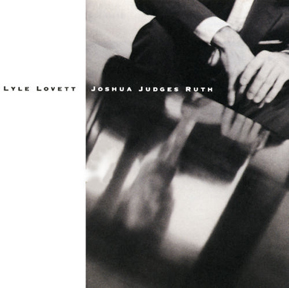

LYLE LOVETT

Joshua Judges Ruth

Curb (1992)

The 1970s wave of “outlaw” country musicians were revolutionary in a ruggedly coherent sort of way: Willie, Waylon, Kris, and their compatriots hung together artistically and socially. They looked and sounded like they belonged together, borrowing each other’s tunes and crashing each other’s concerts on a crowd-pleasingly regular basis. But by the mid-80s, the onetime revolutionaries were old-guard hitmakers. They hadn’t lost their renegade spark, but they weren’t necessarily any less likely to chart a tune than tamer contemporaries like Conway Twitty or Kenny Rogers. Occasionally a young upstart like George Strait or John Anderson would enliven things, but in the post-Urban Cowboy years country music was in danger of turning stale, or at least irrelevant to all but the middle-aged middle-America diehards who were convinced country music was the only music worth listening to. In the wake of what the endlessly quotable Steve Earle dubbed “the Great Credibility Scare,” a few higher-ups in Nashville decided they were overdue for a new round of outlaws.

In retrospect, they couldn’t have chosen a more eclectic bunch. Amidst the edgy honky-tonk of Dwight Yoakam, the Buddy Holly-meets-Springsteen growl of Earle, and the college-rock smarts of Foster & Lloyd, Lyle Lovett might have been the oddest duck of them all (or at least a solid tie with a young k.d. lang). His dashing business suits, asymmetric pile of curly hair, and wry-looking mug were sort of a visual preparation for what you were going to get with his music: classy, unconventional, and fascinating in its self-contradicting blend of off-kilter irony and sweet, sometimes-heartbreaking honesty.

It probably seemed a strange gamble for Curb Records in 1986. A few decades later and with full knowledge of Lovett’s continued musical success, it seems even stranger that a man who looked and spoke like a character from a David Lynch movie and sounded more like Randy Newman than Merle Haggard was a good bet for mainstream country music success. But the craziest thing is that it worked, at least for a while. Lovett’s self-titled debut spawned a Top 10 hit and sold hundreds of thousands; the 1987 follow-up Pontiac did at least as well, not wavering a bit from Lovett’s signature vision. 1989’s Lyle Lovett & His Large Band sold even better, but none of the singles got a whiff of the Top 40; the label wasn’t ready to give him the boot, but a re-examination of priorities was in order.

Among the beauties of the “Great Credibility Scare” was that some extremely and unconventionally talented artists got just long enough of a run in the mainstream spotlight to accumulate a career-sustaining number of fans discerning enough to know that someone like Lyle Lovett is not a substitutable good. He’s not the sort of act that’s replaced by a younger version every few years. No one else could have made the records that put him on the map, and no one else could have made Joshua Judges Ruth, the 1992 landmark album that encouraged his ambitions and dispelled any lingering notions that he needed a hit single to survive.

Joshua Judges Ruth meanders, ponders, jokes and confounds and preaches with a singular kind of verve; it kicks off unassumingly enough with the catchy piano-driven blues shuffle of “I’ve Been To Memphis,” all sly winks and ribald puns (“Sherri she had big ones/Sally had some too/Alison had little ones, that hate to go to school …”), but then gets weird in short order with “Church,” a call-and-response gospel shouter that lyrically climaxes with a long-winded preacher apparently eating a live dove in front of his hungry congregation. Then it’s on to the dirge-like one-two of “She’s Already Made Up Her Mind” and “North Dakota” (a rare Willis Alan Ramsey co-write), both slow as molasses but intriguing in their melancholy, and then back to the blues but with a distinctly un-Lovett-like anger on “You’ve Been So Good Up To Now.” And it goes on like this: disparate tales with disparate tones, sifting through narrative imagination and sincere emotion and bound together by the unique personality writing and singing it all. The sweetly heartbreaking “Family Reserve,” the more tongue-in-cheek “Since The Last Time” and the stark “Baltimore” all wrestle with mortality from different angles; “Flyswatter/Ice Water” is about as tenderly specific of a marital love song as anyone could ask for, and “She Makes Me Feel Good” wraps things up on a surprisingly breezy note given the weight of the words that brought us thus far.

The sort of people who were listening to Lyle Lovett at that point – most of whom are doubtless still listening today – knew something didn’t have to be a hit to be a classic. But in its own way, Joshua Judges Ruth was both, a gold record (certified sales of well over 500,000 by now) in a changing paradigm where idiosyncratic approaches could be awarded with enduring audiences. Nearly 25 years later, Lyle Lovett is still a hot ticket as a live act, a prolific recording artist, and one of the world’s most respected songwriters — a reputation that was cemented and furthered by this offbeat triumph of an album. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment