By D.C. Bloom

(LSM Jan/Feb 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 1)

How does one begin to thank the thousands of men and women from our armed forces for their selfless service? How does one help the hundreds who come back from far-flung war zones still bearing the physical and emotional scars that have forever changed their lives and perspectives on life and death?

For Austin-based singer-songwriter Dustin Welch, the answer was as straightforward as three chords and the truth. You listen. You care. You share. And you begin to show our nation’s returning veterans how the power of putting words to song can truly begin to soothe troubled minds and souls.

Welch had joined dozens of other Texas musicians on the Voices of a Grateful Nation albums, two volumes of songs that a non-profit organization called the Welcome Home Project released to raise funds and awareness of the hardships young service men and women face today, both around the globe and here at home. The all-star roster of artists — including Walt Wilkins, Jesse Dayton, Malford Milligan, Ray Benson, Terri Hendrix and many others — sent a much-appreciated and much-needed message that Texas and our finest musicians care deeply about supporting our troops. And that this appreciation doesn’t end when their boots hit U.S. soil upon their return. Still, Welch — along with scores of other concerned Texas musicians — wanted to do more.

Soldier Songs & Voices (SS&V) — which provides free music lessons and songwriting workshops to veterans — is an outgrowth of a earlier effort that the Welcome Home Project had initiated in San Antonio to provide music therapy for wounded warriors suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury and other debilitating conditions. But that program never really took root. With its standard guitar curriculum and institutional environment, it smacked too much of just more structured rehab for veterans who gave it try. “And that’s the last thing they want,” says Welch. So they would check it out for a few weeks, and then tended to drift away. And on more than a few occasions, the donated guitars they’d been given to write songs on would show up on eBay months later.

Welch heard about the program’s frustrations in San Antonio and volunteered to help — convinced that a similar program could work if approached a little differently. “Just from my own life, I know how cathartic songwriting is — and how much music can enrich a person’s life,” he says.

And doubly so for a returning veteran, who may be able to express things in song that they can’t — or won’t — reveal to a therapist. After numerous meetings and much cogitation with the folks from the Welcome Home Project and its founder, Charlie Gallagher, Welch finally said, “Why don’t I just try this and we’ll make it up as we go?” So he set about recruiting fellow musicians who shared his belief that this was something worth continuing in a less formal, but ultimately more effective way.

The key, Welch felt, was to have the gatherings at a music venue, a decidedly more social environment, because the starting point for many veterans is to start interacting with others once again. “When you isolate yourself, which a lot of them do, your problems just get even further into your head,” Welch says. “And that can be a dismal and lonely way to live.”

The harsh reality is that withdrawal — and a belief that no one can begin to understand what they’re going through — has led many veterans to take their own lives. The Department of Veteran Affairs reports that 18 veterans commit suicide every day. And the risk of suicide in the youngest group of vets — those 24-years-old and younger — is nearly four times higher than that of non-veterans. Between 2005 and 2010, service members took their lives at a rate of one every 36 hours. And a truly sobering fact: It’s estimated that this year, for every American soldier killed in combat, 25 will commit suicide.

These numbers outrage Welch. “This just can’t keep happening,” he says.

Taking it to the Cheatham Street

Monday evenings now find Welch and a group of musically curious veterans taking up residence in a corner of Cheatham Street Warehouse, the storied songwriters’ den by the railroad tracks in San Marcos. They’re as much soul-searching sessions and gatherings of new friends getting to know more about each other as they are songwriting workshops.

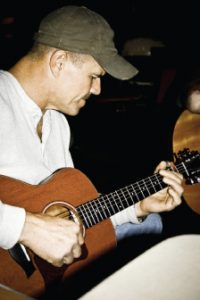

Veteran Tom Kinney calls songwriting a liberating “cocktail of emotion and vulnerability.” (Photo by Melissa Webb)

Tom Kinney is one of the area veterans who attends frequently. He’s a muscular, kind-hearted man, a natural born, self-proclaimed “protector.” He gravitated to the military because he felt it was his calling to help make the world a safer place, something he sensed even as boy, he says, when he heard the song “Bad Bad John,” and felt an immediate kinship with that brave protagonist and one helluva man at the bottom of the doomed mine.

“The military environment forms who you are,” Kinney asserts. “And you’re always going to be different. And you just have issues … you just do. The sooner you accept that the better. And sometimes you feel like you have an anger problem, because the things you hear other people bitch about just seem so trivial.

“But music provides you with a release,” Kinney continues while tuning his guitar. “And what an outlet it is. There’s a real liberating power in it. It’s a cocktail of emotion and vulnerability, but there’s freedom here. And that was totally unexpected.”

A lot of that is because of the harmonious vibe Welch has established. His instructional style is as laid-back as he is. “Sometimes we just free write,” he explains. “And there’s a real sophistication many of the veterans write with. We’ll go through and pick out words and lines, and I’ll help them identify potential hooks and choruses.”

But he also goes the extra mile to really understand what the veterans may be going through. He takes the time to research neurological conditions and better understand the mental gymnastics involved in composing, performing and internalizing music. And he sees the magical results of what the cognitive psychologists study. Welch points to the tremendous strides that Erica VandenBerg, a former Army sergeant wounded seriously in Iraq, has made through the healing power of music making. VandenBerg suffered from Broca’s Syndrome, a condition that greatly impedes one’s ability to communicate, because while the sufferer sees the sentences she’s trying to express just fine in her mind, they come out of her mouth all scrambled up. So while she may think she’s saying “I loved the Voices of a Grateful Nation CDs,” the listener hears “Nation I of loved CDs Voices the Grateful.”

But through the SS&V experience, VandenBerg slowly started to get her vocabulary back and was soon pouring herself into writing songs. Her songs have struck such a chord with Welch that he occasionally performs two of them in his shows — “FOB,” an acronym for the Forward Operating Base VandenBerg operated out of in Iraq, and “War in My Head,” which poignantly describes the battles she fights with her war-damaged brain.

“It’s a great honor that someone values what I put down on paper,” says VandenBerg. “After four years of one rehab after another and basically having my life on hold, I finally feel like I’ve accomplished something because of my music. I was really out of it when I got out of the service. I just didn’t care. And I acted like that when I drove. And I acted like that when I drank.”

She still struggles with seizures and short-term memory loss that makes life an on-going challenge. VandenBerg compares it to what Drew Barrymore’s character deals with in the movie 50 First Dates. But rather than struggling to remember that she’s somehow fallen for Adam Sandler, VandenBerg must continually retrain herself how to make the chord fingering and relearn the progression and song structure she often put in place just the day before. Music therapy, she suggests, helps bring that memory loss back sooner. “It may take a few days to figure things out again,” she adds, “but I’m getting better.”

Spreading the message

While Welch holds down the fort at Cheatham Street in San Marcos, a committed task force of like-minded songwriters and musicians have volunteered their time to help introduce the Soldiers Songs & Voices program to veterans in other towns around the state. In San Antonio, local blues artist Jimmy Spacek and gifted guitarist/gregarious gadfly Maestro Aurora oversee a chapter that gathers at the downtown music venue and eatery Sam’s Burger Joint. Aurora brings more than just musical know-how to the table: his day job at the city’s Lackland Air Force Base is to help veterans get the medical attention and therapy they require. A veteran himself who served more than two decades in the flying corps, Aurora fondly recalls the time Texas guitar legend Jimmie Vaughan stopped by to chat with the group before his evening gig at Sam’s. “What’s the most important thing these guys should know about music?” Vaughn was asked. He replied simply, “Just play what you want to hear.”

Sound advice, no doubt. Some veterans, though, come to Sam’s to play and write among bands of brothers because of what they don’t want to hear anymore. Some are still trying to shake the sounds of war and the cries of fallen comrades that made for countless restless nights in Afghanistan or Iraq … sounds that have followed them back to Texas.

Corpus Christi native and current Brenham resident Michael O’Connor, who collaborated with Jeff Plankenhorn for a track called “Home Again” on one of the Voices of a Grateful Nation collections, hosts a Soldiers Songs and Voices group at the Bugle Boy in La Grange every other Sunday afternoon. According to O’Connor, that group currently skews a bit more towards Vietnam War-era veterans.

“I’m not a therapist, I’m just a guitar player,” admits O’Connor. “It’s an honor to just hang with these veterans who have been back for years, but still are dealing with a lot of issues, such as the effects of Agent Orange. I never could have gone through what these guys have, so I’m real proud to be a part of this. And maybe I’m earning a few points in heaven along the way.”

So when O’Connor can help a veteran sing his first song in public for the first time, he sees it as just a small way of giving back to those whose bravery on the battlefield leaves him in awe. Clearly, it’s a far lesser kind of courage required to take the stage instead of a remote jungle hill, but the value of doing the former in peacetime may be just as valuable — if not more so — than the latter. It all works, O’Connor notes, because “Everyone wants to be in a band.” So he’s invited fellow musicians such as Susan Gibson, Adam Carroll and Woody Russell to drop by and also join this brotherly and sisterly band, lending their ears and years of songwriting experience to the cause.

Every Sunday afternoon, the Saxon Pub in Austin opens its doors to a SS&V group that Owen Temple hosts. “We had a guy recently who finished a song that he said was about things he’d been trying to say to his loved ones for more than seven years,” Temple says. When Temple attended the Voices of a Grateful Nation holiday party at Cheatham Street Warehouse last December, Charlie Gallagher took note of the way that Owen kept sharing guitar and songwriting tips with the attending veterans. “Hey, you’re a natural at this,” Gallagher told Temple. “You wanna do one up in Austin?” Not surprisingly, Temple has had no trouble rounding up additional support for the SS&V Saxon sessions: Chris Wall, Randy Weeks, Plankenhorn and other Austin musical stalwarts have all pitched in.

Houston singer-songwriter Matt Harlan has recently started a Soldiers Songs and Voices group that meets monthly at J.P. Hops House. Harlan was hooked when he attended a SS&V at Cheatham Street with Welch and noticed a distant veteran who “didn’t say a word the whole time and just looked mad as hell at everyone,” as he recalls. But that didn’t deter Harlan from going up to him as the evening’s workshop adjourned. “He didn’t care at all about songwriting, really. He just wanted to talk about gear. And it turned out he was a great guy. But I wouldn’t of known that if I hadn’t gone up to him.” Harlan has enlisted the help of local musician and Vietnam War veteran Jeff Chambers, and, given the city’s population and expanse, they’re making plans to start groups in other parts of Houston and perhaps as far south as Galveston.

Today, there are SS&V bases of operation springing up throughout Texas — and beyond. There is talk of SS&V groups starting soon in El Paso — where a local luthier is stringing together plans — and just down the road from Quiet Valley Ranch in Kerrville. Welch also reports that Chelsea Crowell, Rodney Crowell’s daughter, has picked up the challenge in Nashville and is in the process of pulling together a group along with the Nashville Songwriters Association International. Shortly after starting his group in San Marcos, Welch was touring in Colorado, when he heard talk of a similar effort being led by Tony Rosario. When Welch reached out to him to hear more about their work, he was surprised to learn that Rosario had lived across the alley from the Welch family in Nashville. Soon, the Grand Junction group was a part of the SS&V fold. The SS&V flag also flies in Idaho, in Boise and Pocatello. And according to the SS&V website (www.soldiersongsandvoices.org), programs are also in the works for Portland, Ore., Baltimore, Md., Walla Walla, Wash., and Sarasota, Fla.

Clearly, the idea seems to be catching on. And if every group in every city helps even a handful of veterans cope a little better through the process of making and sharing music, then it’s mission accomplished. Or at the very least, a step in the right direction.

“I’m a firm believer that music is a powerful force,” says Welch. “And that its benefits are much deeper than many think.”

No Comment