By Lynne Margolis

When in the course of human events and July heat, it becomes necessary to pay $4 for semi-chilled water, $6 for Sno-cones and $9 for beer while attending a concert at Circuit of the Americas’ Austin360 Amphitheater, we might hold this truth to be self-evident: that all human cash-cows should be accorded the right to occasional respite from sun and heat without resorting to insurrections against their early-arriving, shade-hoarding brethren.

At Willie Nelson’s Fourth of July Picnic, held Monday, exercising one’s inalienable right to the pursuit of shade was nearly impossible for non-VIP concertgoers and those not fortunate enough to stake territory in the lone misting tent. Good thing the founding fathers signed the Declaration of Independence in July instead of August. Celebrating liberty would be downright deadly during the dog days in Texas.

It should be noted that many outdoor amphitheaters provide covered seating for at least the sections closest to the stage, with remaining seats and lawn areas graded so viewers in those sections can still see the performers. Failure to follow that kind of design plan here, in the land of triple-digit temps and flood-inducing downpours, causes one to wonder, “WTF were they thinking?”

While we’re on a rant, we feel it’s our civic duty to note the supreme tackiness of forcing performers to watch giant screens flashing commercials for upcoming events and sponsor products, as Billy Joe Shaver, Shakey Graves and others delivering sets on the Budweiser Grand Plaza Stage had to do. One can imagine the distraction, if not downright annoyance, those swirling images present.

Let’s consider where else this might have happened. With a reported audience of 10,000, it was too big for New Braunfels’ Whitewater Amphitheater. (It holds only 5,600.) The Backyard Live Oak Amphitheater is still, shall we say, on hiatus. (A July 7 Facebook post read, “Even though we’re a ways from reopening, we want to get your feedback on who you would like to see grace the Backyard stage when the time comes.”) Public properties in Austin require a complex permitting and planning process, and besides, the city does its own July 4 thing. Suburban park areas under discussion as potential sites for festivals, such as Onion Creek Metropolitan Park and Walter E. Long Metropolitan Park, are a long way from being ready. Which doesn’t leave many local options.

But fans who showed up to catch repeat favorites such as Shaver, Johnny Bush, Asleep at the Wheel, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Kris Kristofferson and Jamey Johnson — accompanied by Alison Krauss — seemed to take the Austin360 discomforts in stride, filling water bottles at fountains or the rare refill stand, or forking out.

Some artists spent most of their offstage time on air-conditioned buses, but Shakey Graves got drenched in sweat right along with the crowds well before his own set, standing right in front of the Pavilion stage to worship at the feet of Kristofferson (who later watched Johnson’s set from the wings, inspiring Johnson to render “For the Good Times” as an homage to his idol.)

The sun beat directly on both performer and audience as the revered elder statesman delivered his classics; at 80, his voice is wavery, but thanks to his diagnosis and treatment for Lyme disease, he’s more present than he’d been recently. There’s still something compelling about hearing the author of “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” “For the Good Times,” “Me and Bobby McGee” (complete with now-obligatory Janis reference) and “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down” sing these tunes — even if he does seem a little, well, drained.

A spry Shaver, on the other hand, had no problem keeping up his energy (and, dare we say, redneck-leaning cred) at Texas’ version of “Oldchella” — a term we use with affection and respect, BTW, because we’re all heading in that direction. If we’re lucky. But at 76, he brought up the rear of the seven-decades-plus club; fellow 76-year-old David Allan Coe had to cancel due to illness, and a bus breakdown prevented 74-year-old Leon Russell’s arrival. Ray Wylie Hubbard has a year to go before he joins; Asleep at the Wheel’s Ray Benson has five. But just adding up the years Nelson (83), Kristofferson and Johnny Bush (81) have been around, you get a number higher than the age of the country itself.

Which begs the question of why? Why spend hours and hours in triple-digit heat and pay prices that evoke images of real highwaymen — the robber kind, as opposed to the surviving members of a certain legendary band — to see artists who may have lost a bit of stage presence or, even if they still might captivate under different circumstances, aren’t as likely to do so in these abbreviated sets before sweltering audiences? This is a question that keeps some music journalists up at night, wondering how to characterize such seemingly masochistic exercises in endurance while fairly reporting the events witnessed.

But let’s put that question aside for a second to consider the curious age contrast with the female side of the bill. Because Willie’s daughter Paula also had to cancel her scheduled appearance, 49-year-old Lee Ann Womack was the oldest woman onstage Monday. Alison Krauss is 44. They were also, without doubt, the highlights of an event that was, frankly, short on thrills.

These daylong affairs are generally vehicles for delivering greatest hits and crowd-pleasers — exactly what most concertgoers want. But for those who sought something more — more nuance, more feeling — they had these ladies, and not a whole lot else. (Unless they really were there for Brantley Gilbert, who, like Eric Church in 2015, was booked to draw the ticket-buying bro-country contingent.)

For as much of her set as we got to hear, country it-girl Margo Price sounded impressive, but not yet near Womack’s level. (Sadly, a parking attendant who wouldn’t let us into our designated area cost us, and others, a half-hour spent driving between entrances before a supervisor stepped in; that thwarted our plan to catch her full set.)

From the minute Womack opened, it was clear the golden-voiced Lone Star native, wearing the label “Texas Girl” on her T-shirt, should have been given more than 35 minutes onstage. She delivered her delicious take on Julie Miller’s “Don’t Listen to the Wind,” followed by “A Little Past Little Rock” and “I’ll Think of A Reason Later,” before soaring on her Grammy-nominated cover of Hayes Carll’s gorgeous “Chances Are” and the title track of the album it’s on, The Way I’m Livin’. Then she sent it home with her biggest hit, “I Hope You Dance.” (It was also a pleasure to see her accompanied by one-time Austinite Pete Finney on pedal steel and acoustic guitar.)

Graves’ same-length set also seemed short, especially because his energy, humor and ability to interact with his audience give his shows an unpredictable quality that’s exciting to witness. He moved constantly, thumping his suitcase percussion kit with a red Chuck Taylor-clad heel or effects pedals with a toe while conjuring feedback from a guitar or his keyboard, or swinging his hips to drummer Chris “Boo” Boosahda’s beats while singing in his ethereal falsetto. On this day, he also tossed baby beach balls — and his cannabis leaf-adorned trucker’s hat — into the audience during a set that went a little deeper into his catalog with “Bully’s Lament,” “Roll the Bones,” “The Donor Blues” and “If Not For You 5,000.” As the setting sun finally delivered some relief, he rounded it out with “The Perfect Parts,” “Family and Genus” and the sing-along, “Dearly Departed.”

Krauss and Johnson, fortunately, got 75 minutes, for a set full of sublimely covered classics that paid respects to their many idols, along with a few Johnson originals. “Make the World Go Away” and “How’s the World Treating You” segued into the Band’s “Ophelia,” into which they inserted a bit of “Dixie”; later, they also covered “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.”

Proving once again that her Grammy record is no fluke — with 27 apiece, she and Quincy Jones are tied for the most wins by a living artist — the angelic Krauss delivered gorgeous vocals on “Ghost in This House” and “When You Say Nothing at All.” And Johnson, who’s playing and singing style almost make him sound closer to Willie’s heir apparent than Lukas Nelson, his own son, offered heartfelt treatments of “In Color,” “That Lonesome Song” and his Merle Haggard tribute, “Footlights.”

Just when it started to feel a little too low-key, lights illuminated the giant American flag backdrop and the audience started to chant ”USA. USA.” That’s when Johnson and Krauss delivered what felt like a much-needed reminder of what Independence Day is all about, with Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land.” After Krauss’ violin solo, Johnson sang the fourth “missing” verse:

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said ‘No Trespassing.’

But on the other side it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

Cheers arose from the crowd. He skipped the more-incendiary verses after it, but at least he reaffirmed the classic sing-along’s status as a protest song — a rare species in some country music circles.

Good thing, too, because after a fireworks break, the audience was subjected to Brantley Gilbert, a bro-country character whose act is so lowest-common-denominator, it would have been high comedy if it wasn’t so obnoxious. The musical caterwaul emanating from the stage, inflicted by a bunch of rawk dudes who apparently never met a riff they didn’t want to steal (Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner”? Seriously?), was interrupted only by a speech that could have been written for a certain candidate. Wearing an American-flag tank top, Gilbert strapped on a matching flag-painted acoustic guitar before offering prayers for the troops, then mentioning how much he loves his family, his job, his band and his guns. “I also want to say something about cancer,” he continued, somehow mashing together a dedication to any people who might be fighting for their lives or their country. As the band played, the big side-stage screens showed images of stained-glass windows with rays of sun shining through.

Yes, Gilbert likely sold more tickets. Yes, many fans dug his shtick, which more closely resembled bad heavy metal than country music. But watching that, while observing some audience members cavorting in holiday get-ups that rivaled Halloween regalia, made one ponder, again, exactly what we were here to celebrate.

Fortunately, the picnic’s founder helped set us straight with his gentle presence. It’s almost redundant to list Willie’s setlist, it changes so little these days. And the thrills come more from his still wondrously dexterous playing on the ancient, ageless Trigger than from his weakening (but still melodic) baritone. But when he crooned “Ain’t It Funny How Time Slips Away,” of course it caused a little tug on the ol’ heartstrings. “Always on My Mind” evoked a similar sense of nostalgia.

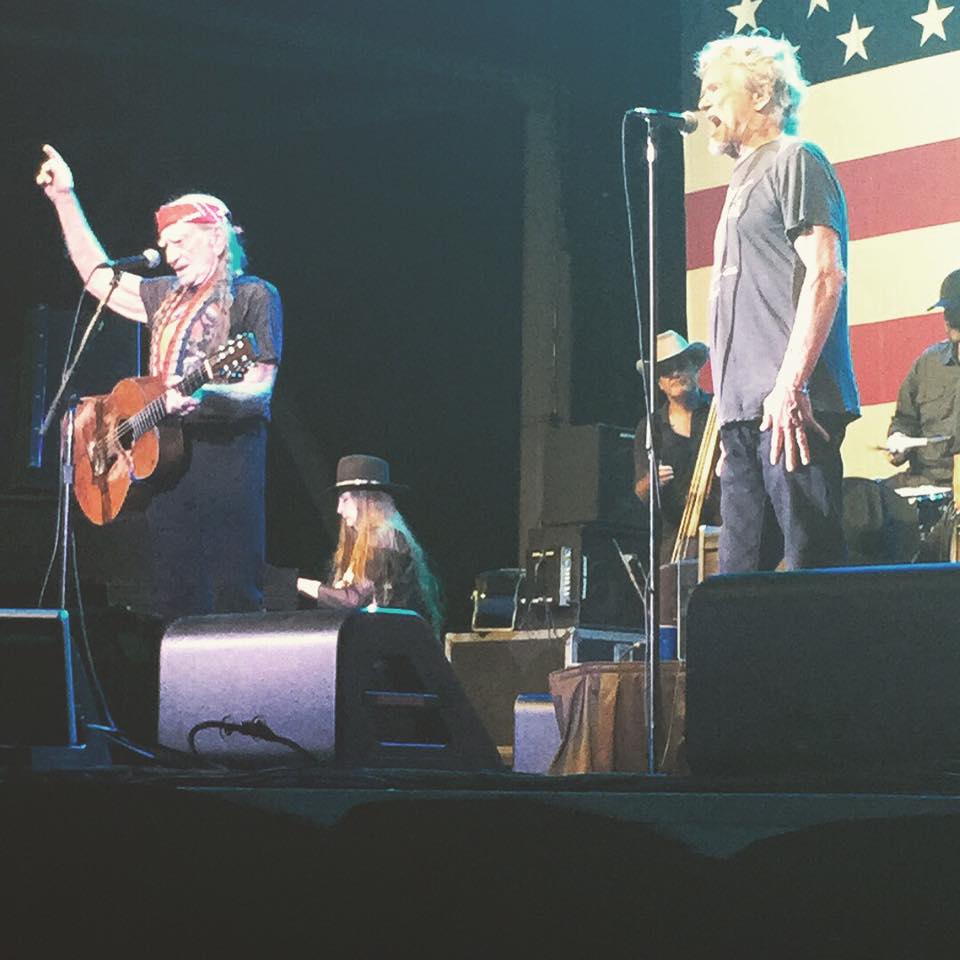

When he brought Kristofferson onstage to duet on “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die,” a humorous, but very likely true last wish, anyone still present had to wonder if this might be the last blast for either legend.

And that, of course, is what keeps them coming. It isn’t because they expect stellar performances (and if you pay enough, and drink enough, you’re more inclined to think an artist’s performance is stellar anyway — especially if it’s your first time). It’s the same reason fans are paying ridiculous sums to attend that October rock summit out in California. We’re all mortal, and the longer we hang around, the shorter our odds get.

Might as well catch ‘em while we can.

In air-conditioning, if possible. And without the pretenders.

Bitch Shut Up. It’s the middle of summer in Texas 2016 what do you think will happen? Its hot, no shade, costs money. Sorry you weren’t born yet when it was at Garner State Park and great but get over it, you are just one more spoiled little kid who never had to go to school with air conditioning.

Who you calling bitch? Don’t bring that trash talk home when you come visit.

C of the A leaves much to be desired for a concert.