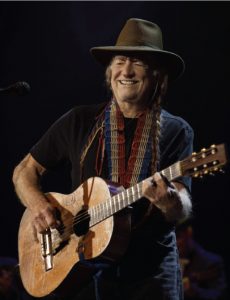

Director (and Willie pal) Billy Bob Thornton pays tribute to “The King of Luck.”

By Lynne Margolis

(LSM May/June 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 3)

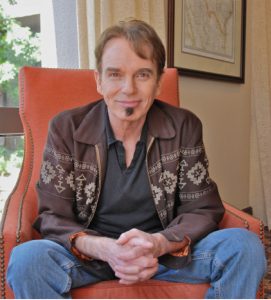

When Billy Bob Thornton was approached about helming a Willie Nelson documentary, he thought it sounded like a cool idea. But when the financiers pulled out and he was left holding the proverbial bag — including a bunch of already-hired film people looking at him with “what now?” expectations — he decided to jump in and do it anyway, financing it himself.

It’s a much smaller movie now, but as Thornton points out, that’s the way Willie would do it anyway: less fuss, more casual and intimate. As it happened, Thornton’s band, the Boxmasters, were out on the road with Nelson, so they grabbed a bit of concert footage. But during an interview in an alcove of the Four Seasons Hotel just before The King of Luck made its South By Southwest world premiere, Thornton said he purposely set out not to make a concert documentary or A&E Biography piece. Instead, he contacted Nelson’s family and several of his friends — many of whom happen to be Thornton’s friends, too — and invited them out to Willie’s place in Luck (the movie set/grownup playground Nelson has out by his Pedernales studio/golf course spread in Briarwood). As Thorton explains, most of the film “is this extended family of his telling why they love him and why they’re loyal to him and he’s loyal to them.”

Of course, that extended family includes the Family Band, Nelson’s longtime posse of stagemates: Sister Bobbie, Paul English, Bill English, Bee Spears and Mickey Raphael. It also includes retired University of Texas coach Darrell K Royal; fellow musicians Freddie Powers, Jimmie Vaughan, Joe Ely, Bobby and CoCo Whitlock, Ray Benson, Ray Price, Shelby Lynne, Kris Kristofferson, Kinky Friedman and Billy Joe Shaver; actors Woody Harrelson and Owen and Luke Wilson; and Nelson’s kids. Unfortunately, friends like former President Bill Clinton, U.S. Rep. Dennis Kucinich and Lyle Lovett were unavailable, and indie budgeting meant they couldn’t fly people around to get interviews.

But the hardest part, according to Thornton, was having to switch from friend mode to documentarian.

“Normally, a documentary filmmaker is really an outsider,” he notes. But these were people he was around all the time. “If I was interviewing my best friend, we’d be laughing and you’d turn the tape on and it’s like, ‘Now let’s act like we don’t know each other.’ We have to act like this is all official, so we would crack up half the time.”

He also had to work at “not being a pain in the ass.” When you’re the subject of a documentary, he says, normally, the internal reaction when the interviewer comes around is, “Get that guy outta here.”

“I didn’t want to be that guy,” Thornton says. “I mean, documentary guys can be very pushy.”

The best aspect of the experience, he admits, was hearing from everyone just how they feel about Willie — something none of them discuss in regular conversation.

The film — done in black-and-white — is separated into segments: the crew, the family, the band and Willie.

“The funniest stuff you’ll hear in the thing is probably from the crew and the band,” says Thornton. “Mickey Raphael is fantastic; he’s a great interview.”

As for what they have to say about the Red Headed Stranger, Thornton says it’s not like a roast or an exposé — more of a reverent tribute.

“They’re really talking about why they love him, why they’ve been part of this big, crazy family all these years and what he means to them and what they mean to him. He’s been very loyal to a lot of people.

“You see all these people around Willie, and it’s like, ‘Are you payin’ all these folks? How in the world do you afford this?’ Maybe that’s why he’s on the road 300 days a year!” Thornton says with a laugh. “But he’s very loyal. He has a bigger posse than rap groups.”

One of those people was road manager Poodie Locke, who died just days after shooting wrapped. Thornton says he and Locke had just talked about Poodie’s desire to do a film project together. “He was real serious about wanting to get some things done … he never talked to me about stuff like that,” Thornton says.

Locke’s death emphasizes an important, if unspoken, undercurrent to the project, a “get it done while he’s still alive to appreciate it” element. It’s easy to think a guy like Nelson might stick around forever, but the death of 97-year-old Pinetop Perkins just days after Thornton discussed this project drove home the fact that this could very will be the last documentary to feature perspective from the living, breathing man himself.

“It’s something that we’re real proud of,” says Thornton. “You won’t see anything fancy in it, and I don’t think Willie would want anything more than that.”

No Comment