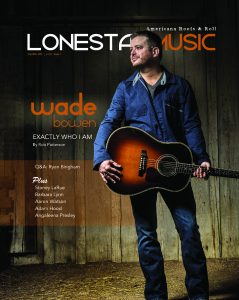

By Rob Patterson

(LSM Jan/Feb 2015/vol 8 – issue 1)

There are, every now and then, occasions in an artist’s career when the things that really matter come together in near-magical congruency: the stars align, they hit their stride with all pistons firing — however one might wish to describe it — and they have their moment. And it’s their time to shine.

Right now, Wade Bowen is having that special moment. And in the Texas/Red Dirt movement as well as beyond, it is his time.

You can hear it loud and clear on his latest album, his fifth studio recording but the first to simply be called Wade Bowen — an apt title for such a seamless and cohesive collection of his strongest songs to date. You can feel it in his energetic and joyful live performances, plus witness the effects of an artist hitting his musical sweet spot in the audience he draws. You can also detect it in what Bowen has to say.

He’s almost dumbstruck yet still proud that the record that bears his name as its own is far and away his best ever. “We were sure trying for that,” he admits. “I’ve always tried for that, but over the years I’ve just gotten older and — I don’t know about much wiser, but I have figured out a little more how to do it …”

“I felt like it was hitting a big reset button for me,” Bowen continues. “All of it.”

Part of that stems from the fact that Wade Bowen is his first release after parting ways with Sony Nashville, their short marriage proving to be an all-too-familiar example of an artist grabbing the brass ring of a major-label record deal only to see things now quite work out as planned. But it’s not every artist who comes away from such an experience not only unbroken, but better than ever and with self-confidence to match — not to mention a Top 10 record on the Billboard Country chart and a first-ever gig on national television (Bowen is scheduled to appear on Conan this January).

“I don’t know if I’ll ever beat this record,” he says. “I really don’t. I hope I do. But I think for this moment in time it has captured my life and career. I felt it from the moment I finished it: This is going to be a very special one for me.”

“I don’t know if I’ll ever beat this record. I really don’t. I hope I do. But I think for this moment in time, it has captured my life and career. I felt it from the moment I finished it: This is going to be a very special one for me.” (Photo by Rodney Bursiel)

* * *

It’s early November, a week and a half after the official release of his album, and Bowen is running a little late to our interview meeting and meal together at Herbert’s Taco Hut in San Marcos, a mutual favorite about halfway between his home in New Braunfels and mine in Austin. He apologizes via text, then again shortly thereafter — and rather profusely — the moment he arrives at the restaurant and finds our table. Nevermind that it’s a rare day off from the road for him and that his brief holdup was merely on account of something or other to do with spending time his two young sons, Bruce and Brock: Bowen is nothing if not polite. You get the feeling from his down-to-earth demeanor that his mama raised him right, and — as Wade’s brother-in-law and longtime friend Cody Canada offers straightaway — that he’s just an all-around “good dude.”

He’s also about as Texan as it gets, even though he’s presently wearing a Boston Red Sox ball cap. “I’m more of a Rangers fan,” Bowen clarifies for the record, “but I have some buddies who play for the Red Sox, so as long as they aren’t playing the Rangers, I root for them. I actually played this benefit last night down in Boerne in Tapatio Springs for Josh Beckett [a native of Spring who pitched for the BoSox]; he’s got this big fundraiser deal, so me and a couple of guys went down there and played for his party. It was a lot of fun. Now that he’s retired he’s pretty much hanging down around here a lot. Great guy.”

Bowen knows from sports: For more than a decade, he and his wife Shelby have hosted an annual celebrity golf tournament and concert — the Bowen Classic — in Waco, and prior to picking up the guitar in his late teens, competitive sports was at the core of his life. “I went to a pretty small school, so I played everything — football, basketball, golf, track,” he says, albeit noting that, being shorter than the usual hoops players and smaller than many out on the gridiron, “I got knocked around a lot.”

But even during his days as a high school jock, he nurtured a serious jones for music, too. “I still was obsessed with music,” he recalls. “I’d tell all my friends — even though I was still a little shy to sing around them — that that’s what I wanted to do. But I had no clue about how to do that, and I wasn’t really interested in figuring it out when I was a teenager. Then I got the bug when I was 17.”

Then, during his freshman year at Texas Tech, Bowen saw Robert Earl Keen, “and it changed my life.” Soon after that, Bowen started his first band, West 84.

“I was always under the assumption that I’d have to move to Nashville, wait tables, wait in in line for my turn for a record deal, as 98 percent of the artists in country do — go up there and wait your turn,” he notes. “Play the ballgame, right? When I saw Robert Earl, I just went, ‘Hold on, you don’t have to do that.’ So I immediately went and started a band. The rest is history. All because of him showing me that you don’t have to move; you can stay here.”

It wasn’t just Keen’s maverick approach to building a successful music career that made a lasting impression on young Bowen, though; he also keyed in on the Texas legend’s craft and commitment to great songwriting. “I think I was — and still am — trying to learn so much, and why they write the songs they do,” he says of Keen and the other Texas songwriting greats that came before him. “I think with the Robert Earl stuff, like his first album, he’s telling all these stories. I was just really intrigued by that, beause I really hadn’t heard a whole lot of that before. And Guy Clark painted pictures I’d never heard before. You hear all this mainstream commercial stuff, and then you start digging into Guy Clark … I was mesmerized.”

Not that Bowen quite had the knack for writing to that level himself when he first started out. An early show of his with West 84 that this writer caught in the late ’90s at Austin’s Stubb’s (on the smaller indoor stage) left little impression. The college kid from Lubbock was earnest in his music making even then, but headliner Bruce Robison’s cannily emotive songs overshadowed Bowen’s opening set by many miles. Bowen’s dogged determination did win him some loyal fans on the then still burgeoning Texas/Red Dirt music scene, but he’s the first to admit that his first compositions and recorded efforts weren’t all that special. “There was one before Try Not to Listen that I made when I was like 20 years old,” he recalls a little sheepishly. “We sold it for a while and finally I said, ‘Hey, we’re not making any more those.’ It was pretty bad. I was still trying out how to write songs.”

Some of those early efforts had legs, though. At a performance Bowen played at Austin’s Belmont in late September, he introduced a song called “Who I Am” as the third one he ever wrote. It held up surprisingly well even next to some of his best songs of more recent vintage, and the overwhelmingly enthusiastic reception it received by the crowd made clear its history as a fan favorite. But as energetically as he performed it that night, Bowen expresses ambivalence about the composition when I ask him about it. “It’s one of those songs that I think every artist or writer has where you’re like, ‘Oh God … I’m so sick of that one,’” he admits. “But you have to sing it. Be careful what you write; you might have to sing it for the rest of your life. My brother-in-law has ‘Carney Man,’ and he hates singing it. But I say, ‘Hey, you just have to play it. It’s your own fault for writing it!’ But I just feel like I’ve written so many other songs, I don’t understand why people won’t let that one go. It’s as simple a song as I’ve ever written.”

On the other hand, he’s also written songs where he knows that he’s nailed it. “On this new record, my favorite song that I just keep coming back to is ‘West Texas Rain.’ The more I think about it, the more I play it, I really feel that’s one that … I’d let them play it at my funeral,” Bowen says proudly. “I knew when I wrote it that it was a special song. I felt like when we got it down in the studio that it’s a special song. And then getting Vince Gill to come in and sing on it — that’s icing on the cake to me.”

Ultimately, whether he’s nitpicking at his earliest efforts or discussing how far he’s come in terms of craftsmanship and maturity with his latest album, it’s clear that Bowen takes his songwriting — and with it his drive to keep raising his own bar — very seriously. “Yeah, I do,” he says. “I always have. I’m so scared about not being taken seriously, so scared of being seen as cheesy, not being good enough …”

“I think that’s why I like this record.”

* * *

Truth be told, it wasn’t just the newer songs or even the tried and true “Who I Am” that made Bowen’s September concert at the Belmont so much more impressive to this witness than that easily forgotten show at Stubb’s back in the day. The entire set was very nicely balanced between country and rock with the occasional pop hook or flourish, in essence not too far removed from a lot of mainstream country but refreshingly free of the heavy and syrupy cheese too often slathered onto Music Row creations. It was also similar in stylistic mix to what’s become the core sound of the Texas/Red Dirt music scene, but with a depth and resonance that’s not always so readily apparent in a genre that all too often seems content to just rest on Lone Star laurels, as if anything that’s not from Nashville is somehow “good enough.” The band played with richness and dynamism, Bowen sang with commitment and utterly true sincerity, and together they formed a communal bond with the audience that was as palpable and strong during the more meditative moments as it was at its most upbeat and fun. And the fact that a substantial portion of that audience happened to be rather attractive women was also hard not to notice.

Bowen laughs when I commend him on that last point, and smiles as he points out an old showbiz maxim: “I hope so! That’s how you get the guys there!”

Joking aside, though, I ask him about the root of this appeal his music clearly has with the ladies. Bowen’s a good-looking fellow, but his boyish attractiveness (not to mention his clear commitment to his wife and family) doesn’t really scream chick magnet. Could it have something to do, perhaps, with him having grown up the only boy among three sisters?

“I don’t know,” he shrugs, stumped. He ponders the question for a further beat or two, though, and concedes that all the women in his family had to have been a factor. “It’s gotta be a big influence in my songs because of my sisters and my mom, the four people in my life that are very … well, the foundation of what I write about and think about. There’s probably a ‘sweet’ factor in my music that the girls feel. It’s not angry, it’s not pissed-off, so maybe that’s the reason. I really don’t know, though. I never really try to think about it or try to figure it out.”

One thing’s for certain, though: Music was a constant presence in the Bowen household throughout his entire childhood in Waco. “Music was such a staple of growing up, it was just embedded in my family,” he explains. “My sisters never pursued music as a profession, but they’re just as passionate about it as I am. Same with my mom. Music was always there. She was always singing. We were always dancing. It was just a very rare time when music was not playing at home.”

And the music playing in the Bowen home, he notes, was almost always “well, country. Country and country and country!

“My Mom was really into Patsy Cline,” he continues. “And my older sisters [Tammy and Tracy] were really into mainstream kind of music: Alabama. They used to drive me around to Alabama shows. Alabama was my first concert when I was 5 years old.” Naturally, Bowen fit right in on 2013’s multi-artist salute, High Cotton: A Tribute to Alabama, cutting “Love in the First Degree” with Brandy Clark. “I think my sisters were more excited about that than I was,” he laughs. “And I was pretty excited.”

When Bowen got a little older, his sisters became similarly obsessed with Garth Brooks and George Strait. He also picked up a love of the Eagles from his mother, and — from his dad — Willie Nelson.

“I always associate Willie Nelson with my dad,” Bowen says. “Growing up my whole life, I thought my dad didn’t appreciate or didn’t like music as much as the rest of us did. But then, when I got older, especially when I started writing songs, I realized that he was the real smart one in that he was listening to Guy Clark and Willie, Waylon and more obscure stuff that I didn’t know much about. And I just was amazed at that stuff once I discovered it, and we started having conversations about it.”

All of those songwriters that his dad loved so much would have a big impact on Bowen’s approach to the craft. But it wasn’t until a few years after he started playing that he belatedly discovered — via a cousin — the artist who today is his biggest musical hero: Springsteen. “He’s my favorite,” Bowen says definitively. “I named my son Bruce! And I don’t know why the fuck I didn’t discover him sooner because he has become, of all the influences in my life, far and away No. 1 — the biggest influence of my entire career.”

The influence of the Boss is easy enough to spot on Bowen’s latest. In the same way that cars, thoroughfares and people in motion are consistent themes over Springsteen’s catalog, travel is a major thread through Wade Bowen.

“I also like the fact that he’s 64, and he’s as relevant or more relevant than he’s ever been,” Bowen marvels. “It’s so cool to see that. You go see Springsteen and he still runs around like he did when he was 25. I also like seeing artists like Guy Clark, who’s 71 now and still writing great songs. They’re still relevant to me.”

The curious thing about that, though, is that even as he looks up to heroes like Springsteen, Keen, Clark, and Nelson who continue to make music that inspires him well into their 60s, 70s, and even (in Willie’s case) 80s, Bowen has been a fixture of the Texas/Red Dirt movement for long enough now — 16 years — that for many college fans and aspiring young artists coming up on the scene today, he has become something of an elder statesman himself. At the ripe old age of 37.

“It is funny,” he says, shaking his head. “I don’t feel that at all, but I’ve been getting that a lot with this record. So I guess I am the ‘older guy.’ [Kevin] Fowler and I were talking about it last night: ‘I guess we’re the old guys and we’ll just try to help the younger ones as much as we can … We’ll get out our canes and wheelchairs and go hang out on a porch somewhere and play!’”

He laughs, of course, but it’s apparent that he’s also duly humbled by the notion and conscious of the responsibility it entails.

“If people wanna look up to me, I always am happy to give them time and advice,” he says. “I believe I’m very kind to the younger guys because I appreciated the times people were kind to me. I’m always reminding myself of when people were assholes and the people who were nice, and try to learn from everything.

“But … I still look at Robert Earl and Lyle Lovett and those guys as the veterans,” he continues, then laughs again. “Even Pat Green and Jack Ingram … let them be the ‘old guys.’ I still wanna be the young guy!”

Although Green himself is only five years older than Bowen, he was already one of the biggest names in Texas country when he took the younger fellow Tech alum under his wing. “Pat saw me, and he was one of the guys who helped me when he didn’t have to,” Bowen recalls. “He was as big as he ever was in his career and he called me, and said, ‘I think it’s time. You and me need to write a song together.’ I was like, ‘Why do you want to write with me? You could write with anyone in the world.’ And he was like, ‘I like you. I think you’re good.’

“So he and I wrote ‘Don’t Break My Heart Again,’ and it came out, and that started the decline of Pat Green,” Bowen continues with a laugh. “I’m kidding! But ever since he’s been telling everybody how much he likes my voice and my songwriting.”

Cody Canada and Cross Canadian Ragweed also provided crucial early support for Bowen. “I met him in Lubbock,” recalls Canada, who now fronts the Departed. “We were gigging out there and he came out to the show. I didn’t even know he was a musician, but to be honest we hit it off that very first time. Then I found out later he was a musician and we started adding him to our shows. He’s one of the first people we met when we stated coming down to Texas. He always treated us real nice, he had really good taste in music … and I was fortunate enough to have him marry into my family.”

“If people wanna look up to me, I always am happy to give them time and advice. But … I still look at Robert Earl and Lyle Lovett and those guys as the veterans. Even Pat Green and Jack Ingram … let THEM be the ‘old guys.’ I still wanna be the young guy!” (Photo by Rodney Bursiel)

* * *

Buoyed by the support of friends like Green and Canada early on — not to mention the continued refinement of his craft and tireless work ethic — it wasn’t long before Bowen was an established top-drawing Texas music act in his own right. A pair of well-received records for the short-lived, Texas-based Sustain label — 2006’s Lost Hotel and 2008’s If We Ever Make It Home — along with a popular Live at Billy Bob’s release in 2010, eventually landed him not only on Nashville radar, but on the roster of BNA Records as part of the Sony Music family. By 2012, he was next in line — like Green, Ragweed, and several other popular Texas/Red Dirt acts before him — for the proverbial Big Dance on the national stage.

It turned out to be a rather short dance, and an awkward one at that. Within a year the whole deal had gone sideways, and Bowen was back to square one and hitting that aforementioned “reset” button — albeit for better for more than worse.

“It was just bad timing all the way around from the moment I got there,” he notes of his tenure with the major label. “They’re great people and I love ’em, but there was a lot of hiring and firing: a new president came in, and there were people coming in and going out the door every week. And, you know, I probably could have been more patient on my end. But we had so much going on and I felt it was a critical time. I like to move a lot faster I guess.” So after only one album with BNA, 2012’s The Given, “we kind of agreed to disagree.”

“It was a weird release,” Bowen continues. “We messed it all up — we meaning Sony and us, too. We came up with this idea to release it regionally because we needed new music out for the fans, and then we were going to re-release a fuller extended version with more songs and stuff a few months later. So they didn’t put anything into that [first] release, and all of a sudden it debuted at No. 9 on the Billboard

charts and they started going, ‘Whoa! This should probably be worked more!’ But they never got to the next portion of the record release. Instead, they told me they wanted me to go back into the studio, but I’d already cut 14 songs for them for [the longer version of] The Given. So none of it was making sense to anybody. The single ‘Saturday Night’ got to No. 39 on the Billboard charts, and then they hired and fired people and it just fell apart on its way up. And then they never jumped on another single. To this day that’s the one thing more than any of it that I will never understand, is why they never went ahead and jumped on another single. They just sat on it for a year, and finally I just said, ‘I guess you have no plans to do anything for me, so I’ll just go do my own thing.’”

His frustration at the way things went is clearly evident, though he insists that he harbors no hard feelings for the people he worked with during that time. “Gary Overton, who’s the president of Sony, I still talk to him all the time,” Bowen says. “He’s a tremendous human being, I love him to death, he’s been so good to me. And years from now we’ll have that conversation of, ‘Man, it would have been fun.’ We get along so great, and I really do miss working with him and a lot of those people at the label. I think we could have done a lot of cool stuff. But it was both of us: they messed it up, we messed it up; we could have been more patient.”

All things considered though, he seems to have come out on top.

“I think a lot of that really went into this record,” Bowen observes. “Because of all of that I made the best record of my career. Because of all that I really … I stopped … I don’t want this to sound bad, but I stopped caring so much. I stopped looking towards what I didn’t have yet in my career and started to embrace what I did. I did that in my personal life, too. It’s such a more pleasurable way to look at things.”

What’s more, Bowen’s short time with Sony did help him continue to expand his touring radius. “We’re going to the West Coast twice a year now, the East Coast once a year, and the Midwest two or three times,” he reports. “That’s a lot of out of state, out of our region, out of our norm work.”

And he got to know producer/engineer mixer Justin Niebank, who prior to Wade Bowen also worked on The Given and has a long list of production credits that includes country acts both older (Vince Gill, Marty Stuart, LeAnn Rimes, and Patty Loveless) and new (Eli Young Band and Ashley Monroe) as well as such diverse artists as Sheryl Crow, Blues Traveler and the Iguanas.

“I think Justin is such an incredible producer,” Bowen raves. “I love to see what he does, and usually it’s a drastic change from the original. We went to this studio outside of Nashville called the Castle. There is so much vibe in there. Here we are in the middle of nowhere, holed up, and in a few days we made the record from start to finish. That was the first time I’ve done a record like that; the other records I’ve done in pieces, doing three or four or five songs at a time just to kinda hear what we have.”

At the very beginning of the sessions, Bowen says, Niebank sat him down with the musicians and told him, “Tell them what you told me — tell them why we’re here.”

“I said, ‘Well, we’re here to have fun,’” Bowen recalls. “‘All the stuff you were told in this town that you can’t do, all the stuff that you’re afraid to do … this is the record where you don’t have to worry about freaking us out. Try to freak us out. Have fun with it. We can always go back and do it again. This is a record for us to just have a blast making together. And I want to hear that when I listen back.’”

Bowen smiles at the memory. “There were a couple of guys at the end of the deal who were thanking me, saying, ‘I needed to kind of get this off my chest, to have fun and play some really fun music and not worry about it being radio friendly or any of that. It was great for us, we all needed that.’ And Justin said the same thing: ‘We needed the monkey lifted off our backs.’”

Bowen did, too.

“It’s funny how … I always have fun making records — I remember the fun of it; but at the same time I was always so caught up in making everything right instead of just enjoying the process,” he says. “So it was a real blast to just have that no-fences approach, where you can’t make a ‘mistake’ and you can’t record the ‘wrong song’ because there’s no such thing. I told Justin, ‘I don’t care if every song on this record is six minutes long; if it feels right, I don’t care about radio. I don’t care about success. I don’t care about anything. I just want to get this record out of myself and that’s all this is for.”

The end result wasn’t just “another” record for Bowen, but a definitive statement of both purpose and identity; one that, to borrow the title of that “simple” little song he wrote way back when, announces, “This is ‘who I am’ now.” As such, it could only be ever be called one thing.

“People could ask me, ‘Why’d you name it Wade Bowen?’ And I could go, ‘Because it means a lot to me. And it’s honest.’”

* * *

Since its release on Oct. 28, Wade Bowen has already proven itself to be one of the most successful — commercially and critically — records of its maker’s career. Like The Given before it, it debuted at No. 9 on the Billboard country chart, and the buzz it’s generated — including that appearance on Conan O’Brien’s late night TV show — is unlike anything Bowen’s experienced before in his 16-year run. But here’s the topper: he’s already got his next record in the can and ready for launch this spring or early summer — and odds are it’ll be even bigger.

It won’t just be his name on it, though, because that next record is a 50/50 collaboration with his friend and frequent co-writer, Randy Rogers. After years of playing wildly popular acoustic duo gigs together under the banner “Hold My Beer and Watch This,” they’ve finally gone and made a record together — and one with the help of none other than Lloyd Maines at the production helm.

The two artists have shared a special connection since they first met, back when both were just getting their respective acts together. “He came out to a show in San Marcos I was playing,” Bowen recalls. “I was still in school in Lubbock but I had a gig down here on the Square. Randy was just getting started, too, and he came up to me after the show and said, ‘Man, I enjoyed it. You wanna come back to my house, bring the boys, come party and stay the night? We’ve got this place over here called the White House. And we jam late at night.’

“He had just finished up his first record, Like It Used to Be. He’d literally gotten back the mix that day. At that time he didn’t have a stereo; he had a computer on his desk. But he said, ‘Mind if I play you some of these?’ I was like, ‘sure.’ And I sat there and listened to the entire record almost from start to finish almost. I thought it was really good. And he was blown away that I actually gave more of a shit about listening to that than trying to go get laid that night. Later that night we were passing the guitar around and he was kicking people out because they were talking, and I was like, ‘I think I’m going to like this guy.’ Later on we decided to play some shows together, and we’ve been friends ever since.”

Eventually, Bowen says, “I was like, ‘We’ve been doing this for years, we need to brand this [duo] thing. Let’s give it a name and make it a tour.’ So we did that and it’s really turned into something great. Over the years we’ve done various things, and I’ve always pushed for us to go beyond just getting up and doing shows. So we recorded the shows, and we hear the recordings, and he’s like, ‘Man, there’s something here!’

Then Bowen unveiled the next part of his plan. “I said, ‘We’re not going to be able to promote it as much unless we have some studio stuff, so let’s go in and do some studio tracks, too.’ So we called Lloyd Maines, who’s someone neither of us has ever worked with before. We went into the studio with a mixture of our bands, kinda combined the two into one. We did three songs and had such a blast that, on our last day in the studio, Randy pulls me aside and says, ‘This is the most fun I’ve had in a long time — let’s do a whole record!’”

They ended up booking another session with Maines and recording another seven songs. Bowen says they have yet to determine what all they’ll pick out of the new studio songs (three covers and seven originals that Bowen and Rogers “never put on record because they were too country”) and the live recordings they already had stashed, but rest assured something’s coming soon. Bowen describes it as a “real ’70s, true country kind of thing,” reminiscent of both Moe Bandy and Joe Stampley and Willie and Waylon. And according to Maines, a bona fide Texas music legend in his own right who has worked with a veritable who’s who of Lone Star icons including Terry Allen, Joe Ely, Keen, and the Dixie Chicks, it’s a keeper.

“Frankly, until that point I hadn’t even met Wade and I barely knew Randy,” the producer admits. “I was aware of both of them, though I wasn’t that aware of their music. But man, it was a great experience. They asked me if I had any songs they might want to cover, so I gave them about eight songs. And one of them was this really old Joe Ely song, ‘I Had My Hopes Up High.’ And I’ll tell you, man … Wade and Randy swapped out verses, and when Wade came in on the second verse, he just burst into it and he sounds exactly like Ely — that cutting edge thing. They did a hellacious version. I can’t wait to play it for Joe.”

Bowen’s uncanny Ely impersonation wasn’t the only quality that Maines took note of, either. “I’m totally impressed with Wade,” Maines continues. “He just sings his ass off. But on top of that he is one of the nicest, most considerate and polite guys. And he takes care of business. So many artists get so wrapped up in the art side of it that they don’t pay attention to the business end of things. But he is right on the spot and totally on top of it.”

On the surface, that complement might seem at odds with the Bowen that made Wade Bowen, the stop-worrying-about-everything-and-just- have-fun guy. But taking care of business — and taking seriously all the other things that matter most, like songwriting, family, and collaborating with friends to make music he’s truly proud of — is exactly what makes Bowen the artist and man he is today. And you won’t find him pretending, let alone aiming, to be anything else.

“Pretty much with me, what you see is what you get,” he says. “I’m a pretty simple and straightforward guy, which I pride myself on, because I don’t think there’s enough regular guys in this business.”

He says he’s been asked a lot lately about where he’d like to see himself and his music going in the future. The answer, not surprisingly, is an honest “I don’t really know … nor do I really care.”

“It’s kind of cool,” he says. “I feel proud and confidant of the decisions I’ve made in my career. And it’s really the first time I feel like I can really say that. No more looking back anymore. Only looking forward. I just want to keep making records the way I made this one. I just want to enjoy the process, enjoy playing for people, and just worry about what I can control. And stop worrying about what can come out of it or what decisions I am making that are keeping me from being a huge superstar, or whether it’s more money or less money … I already make a pretty good living doing what I do. So whatever happens, happens.

“I spent so much time in my career trying to force shit,” he continues. “Now I’m the complete opposite. It almost sounds lazy, but it’s not a lazy thing. I’m just confident. And I’m really open to whatever happens from here on out — just letting go and quit worrying about it. My whole deal is smile more. Smile, Wade, just smile.”

No Comment