By Lynne Margolis

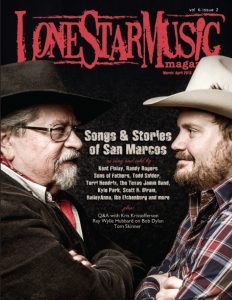

(March/April 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 2)

For the Randy Rogers Band, San Marcos and Cheatham Street Warehouse represent far more than just their college-era stomping grounds. The once tiny town and the rickety little honky-tonk next to the railroad tracks are where they began — literally.

In fact, Cheatham Street and its longtime proprietor, Kent Finlay, mean so much to Rogers and his bandmates, they made the record-label honchos travel there from Nashville when the band inked their deal with Universal’s Mercury Nashville, now MCA Nashville — the label on which they’re about to release their new album, Trouble, on April 30.

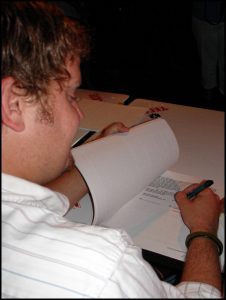

Randy Rogers singing his record contract at Cheatham Street Warehouse on July 30, 2005. (Photo by HalleyAnna Finlay)

“I’m probably a little bit of an emotional, dramatic, nostalgic kind of person,” admits Rogers. “I wanted it to be there with Kent in my little town that I started in, just for the memory, just to be able to say that we did that. And also, it set a tone for us to stay true to what we’ve always dreamed of doing, which is just to make records and to be a band, and not get caught up in the bullshit of the record business.”

Over the dozen years of his band’s existence, Rogers has repeatedly told the story of how Finlay offered him the Tuesday-night slot once belonging to Stevie Ray Vaughan if he could get a band together and commit to working hard.

But there’s more to the story.

“There wouldn’t be a Randy Rogers Band if there wasn’t a Kent Finlay and a Cheatham Street,” says Rogers, whose curly locks surround pinchable cheeks that keep him boyish looking in his 30s. “When I opened the doors to that place, the first time I walked in with my guitar, it really did change my life. It gave me a stage, it gave me an opportunity to play the songs that I was writing for an audience that was already built in.

“Of course, after meeting Kent and learning about the history of Cheatham Street and all the talent, people who were dreamers — he always said that he’s a dreamer, and so many dreamers who came through those doors went on to actually have careers in music, which is what I always wanted to have — it just seemed it was possible,” he continues. “It just seemed like anything was possible. I still apply that to my family life [and] as a working musician, because it’s one of the most impossible jobs to maintain through the years. The confidence that Kent and Cheatham Street gave me, I still use that on a daily basis.”

There was another reason he chose to hold that signing summit in San Marcos — to set an example for the next set of dreamers.

“It’s a way to show other younger musicians that if you believe in yourself and you work hard enough, and of course, if you have the god-given talent, that anything is possible. The things that we’ve accomplished with this band, I never would have dreamed that we could have done.”

Just a matter of time

As for what the Randy Rogers Band have accomplished … well, for starters, singer/guitarist Rogers, guitarist Geoffrey Hill, fiddler Brady Black, bassist Jon “Johnny Chops” Richardson, and drummer Les Lawless managed to get themselves that label deal, and hang onto it for more than six years, through some tumultuous corporate shifts — despite the fact that they haven’t yet notched a top-10 single or become arena headliners. Trouble, their eighth album, is their fourth under Universal’s umbrella. They’ve also scored three Academy of Country Music Award nominations for Vocal Group of the Year and nabbed the No. 2 slot on the Billboard Country Albums Chart for 2010’s Burning the Day; 2008’s Randy Rogers Band reached No. 3.

They’ve opened for John Fogerty and the Eagles, done Leno and Letterman, and made very healthy livings with their 200-show-a-year schedule, which has included touring with Miranda Lambert. On St. Patrick’s Day, they’re opening for George Strait at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo. (Black says his mom is even more excited than he is about that one).

Their first single from Trouble, “One More Sad Song,” finally gave them a top-40 Billboard single — actually, it reached No. 38 — though it didn’t stay there long. Another single, “Trouble Knows My Name” — which features Willie Nelson — topped the Texas Regional Radio Report chart in mid-February, but they’re expecting bigger momentum from “Fuzzy,” a song even more tailor-made than “Trouble” for the Texas/Red Dirt-music loving college crowd Rogers and fellow rockin’ country bands like Reckless Kelly play so well to. That one features Ray Wylie Hubbard, who joined them in Nashville producer Jay Joyce’s comfy home studio to add his mojo.

“It transformed an already cool, groovy song into somethin’ out of this world,” says Rogers.

The title sums up the song’s subject matter, an attempt to recollect a night that got just a little too wild:

Like a TV in a cheap motel

My head feels funny

I lost my keys

I lost my cell

And all of my money

Did I crash a party?

Have a run in with the law?

Take a swim in a fountain?

I don’t know

Cause it’s all kinda fuzzy.

“‘Fuzzy’ is the funnest song that I’ve ever played live,” Rogers says. “I think It’s gonna be an anthem for a lot of college kids.” Laughing, he adds, “It was my anthem when I was in college. I think a lot of people can relate to maybe not remembering all the events of the night before.”

For bands like this one, keeping the spring-break vibe alive is one way they keep their fans close — though unlike Hubbard, who just evokes it in song these days, the RRB guys admit they still push the party envelope themselves. According to Hill, “‘Fuzzy is the song that describes our band more than any song we’ve ever written.”

In fact, things have gotten so fuzzy at times that the whole band once had to check themselves with a Rogers-caused “no-brown-alcohol rule” on the tour bus. And they still follow their annual early-January MusicFest blowout in Steamboat, Colo., with a February dry-out.

“We call it Black February — the shortest month of the year to go sober,” Rogers explains. The guys in Reckless Kelly and Micky & the Motorcars observe Black February, too. They’re all back in fine elbow-bending form by August, however. That’s when the annual Braun Brothers Reunion takes place in Challis, Idaho. Black says MusicFest, where he met his wife, and the Braun Brothers Reunion are two highlights of their year; in true reunion spirit, they bring their families to the latter. Though they missed it last year, they’re already looking forward to this year’s 10th-anniversary gathering, where they’ll hang with Willy and Cody Braun from Reckless, Micky and Gary Braun from the Motorcars, their Dad Muzzie and his brothers, and other artists including the Turnpike Troubadours, the Departed, Wade Bowen and Guy Clark.

“It’s a blast,” says Black (who is not, as far as we know, the reason Black February is so named). “It’s so cool; you wake up and it’s 60 degrees and the mountains are in the background.”

Hill, who prefers “giant cities,” loves tour swings to New York, Chicago and Los Angeles — where he and Lawless “probably did the stupidest thing you can do as a musician, which is, we went and bought skateboards.”

They wheeled all over L.A. — without helmets or pads, the father of three admits. “But I did have some liquid courage,” he adds.

Usually, Black is Hill’s “main runnin’ buddy” on the road. “We really try to tear it up, and post a lot of our antics on the Twitter machine,” says Hill. “If you see people out at the bar partying before the show, you’re probably gonna run into me and Brady.”

No one in the band will confess, however, to being the subject of verse three in “Trouble Knows My Name,” the lively tune from which the album takes its title. Richardson claims they’ve all been sworn to secrecy about the incident, in Missoula, Mont., which Rogers says occurred following an all-day bowling tournament during a tour with Miranda Lambert and Justin Moore. Enjoying their day off, all three bands, crews and the show’s promoters headed to a bar afterward, and someone “had a little bit too much fun celebrating.” As the lyric reveals, the wayward bandmate was invited to spend the night in the local lockup. More than one band can no doubt relate to the verse’s last line: By the time we hit the stage, he’d barely posted bail.

Trouble, indeed

Riffing on a theme of sorts, the band’s video for “One More Sad Song” features an actual storyline involving a bank heist.

“We got to act for the first time ever, which is a new thing for our band,” says Black, who played a rooftop SWAT team sniper. Richardson, who played the hostage negotiator — and who, coincidentally, penned the track titled “Shotgun” — got to drive an actual unmarked police car, racing to an intersection and screeching to a halt. (They all did their own stunts; the kick and adrenalin rush, he says, wore off after the first few tries.)

Then there’s the album cover, which features blowups of each band member’s fingerprints. They’re also offering a package including the album and a T-shirt depicting a pair of handcuffs with the slogan, “Get out of jail free,” and the Monopoly-card promise, “This shirt may be kept until needed or sold.”

As for the Missoula moment, Richardson demurs, “It wasn’t really quite as big a deal as it’s made out to be. The offending party is doing just fine. I don’t think there’s gonna be any long-term repercussions.”

If anything, it’s the opposite. In their first co-write as a pair, Rogers and Hill fashioned the song, based on three actual tour experiences, after Willie Nelson’s “Me and Paul” — and Rogers asked Nelson to perform on it.

“It was a dream come true for me,” says Rogers, who went to the legendary Pedernales Studio in Spicewood to capture their vocals and Willie’s guitar contributions. “It’s the coolest thing that’s ever happened to me in this little short career that we’ve had. Havin’ Ray and Willie on this record really means the world to me, just being from the younger generation of guys comin’ up and [knowing] they thought we were cool enough to help us out.”

Gary Allan also contributed, singing harmonies on “Flash Flood.” And Mickey Raphael, Nelson’s longtime harmonica player, not only adds the choo-choo train propulsion that, along with Black’s fiery fiddle and Hill’s stuttering guitar, drive “Trouble Knows My Name,” he’s responsible for the band’s new love affair with producer Joyce, whose recent clients include Eric Church, Emmylou Harris, Little Big Town and the Wallflowers.

Lost and found

Rogers admits the band was feeling kind of lost after an unsuccessful attempt to record a few tracks with Burning the Day producer Paul Worley. They were seeking some new inspiration when they got a call from John Selman, Nelson’s stage manager, who told them their friend Raphael had mentioned them to his friend Joyce, who said he thought they were great and would love to work with them.

“Brady had done a few sessions with him before, and we were all big fans of the Wallflowers record and some other records that Jay had made, so we were instantly excited and drawn to him,” Rogers says.

Rogers and Hill flew to Nashville and met Joyce at, of all places, Chuy’s, the Austin Tex-Mex institution that recently opened a couple of restaurants in Music City.

“The next thing you know, we’re makin’ a record with one of the most successful producers in the last four or five years,” says Rogers. “It’s another one of those things where you just don’t know what you’re lookin’ for, then all the sudden, it makes perfect sense.

“Once again,” he continues, “that’s Kent Finlay — you know, ‘the harder you work, the luckier you get.’”

All five agree that Joyce’s involvement was a game-changer. Stretching and challenging them in ways nobody had before, he changed up their sound significantly. Yes, it sounds “produced.“ But no, it doesn’t sound soulless.

“Jay is a lot more hands-on than any other producer we’ve ever had. He runs around like crazy. He’s pretty charismatic and energetic,” says Hill. “In the past, a lot of our producers said, ‘You guys do your own thing so well, we’re not gonna try to change anything; we’re just going to capture what you have.’ Jay had a lot of ideas. And he was not afraid to tell us, ‘Hey, why don’t y’all just change this song completely?’”

Black calls him “a mad scientist”; Rogers elaborates, “It was like, ‘Try this, backwards. And flip this upside down. And whatever idea you’re thinking, do the completely opposite of that.’”

They played all kinds of previously inconceivable contraptions; Lawless even found himself beating on metal trays and hitting a banjo with a Leatherman-type all-purpose tool strapped to it.

“Not only is it a lot of fun,” adds Rogers, “it also rekindles that creative little fire that all of us have.”

“Fuzzy” offers a prime example, Hill says. “It has some crazy noises goin’ on in it that I would have never thought to put there. And it really made the song. It has that Jay Joyce magic in it. If our band would have done it without him, it would have ended up sounding a lot more like a blues song. Instead, it sounds … just creepy.”

Actually, it sounds like it’s got some swampland hoo-doo groove on it, enhanced by some ’70s-funk keyboard and Hubbard’s snake-farm charm.

Richardson says he most appreciated Joyce’s enthusiasm and willingness to throw any idea against the proverbial wall to see if it would stick. He also transformed “Flash Flood” into a different song.

Hill explains, “It sounded kind of like a Bruce Springsteen song before. And when he was done with it, it sounded like a country song, and I thought it turned out a lot better because of it.”

Joyce also suggested they invite Jedd Hughes, one of Nashville’s most popular young songwriters and session players, to come in as the “sixth Beatle”; Hughes added mandolin, banjo and some guitar.

They all still swear much affection for three-time producer Radney Foster, an early mentor whom they still honor in many ways, including covering at least one of his tunes on almost every album. This time, it’s the ballad, “If I Had Another Heart.”

“One of my favorite producers to this day is always gonna be Radney Foster,” says Black. “But Jay is a musician, a guitar player, where Radney is a songwriter. And what Jay did for us is push the band, as musicians, a lot further.”

They also preferred his homey basement studio to the one they’d used last time, where the lounge was tiny and they got locked out when the secretary left.

“He got a lot more out of us that way,” says Black. “We were very comfortable in that setting, just because we’re pretty down-to-earth guys. I mean, we all started playing our music in a basement somewhere.”

Fame! Fortune!

From basements, some graduate to places like Cheatham Street Warehouse. And then …

“I think the aspiration is always for world domination,” says Hill. “I mean, we wouldn’t be fair to ourselves, we’d be selling ourselves short if we didn’t at least try.” But he’d just as soon emulate Robert Earl Keen’s success. “They’ve been playing for years and years, same band, same group of awesome guys. They tour the country, they tour the world, and they don’t necessarily break the Top 40, but they make an awesome living and they’re able to support their families doing what they love. That’s what I hope for our band. I’d like to be as big as U2 also, but if we could do it in some sort of Robert Earl Keen fashion, that would be awesome.”

Rogers is a little more philosophical.

“I’ve got a gig tonight, so I’m happy,” he says. “I’m on the road and we made this great record that comes out in April, and I feel like it’s the best album we’ve ever made. All of our families are healthy and our kids are healthy and yeah, I couldn’t be more happy with our position.”

They do wish they could spend more time with their families — especially since experiencing just how ephemeral those relationships can be.

During the course of making Trouble — recorded, somewhat eerily, in a studio named Tragedy/Tragedy — the band endured some painful real-life troubles; Rogers went through a divorce and Richardson’s younger brother and roommate, Cody McLendon, 25, was killed when a driver pulled out in front of his motorcycle. Wearing a helmet wasn’t enough to save him.

You can hear those losses throughout this album; for every “Fuzzy,” there are two sad songs.

Rogers realizes that he’ll never be able to listen to the album without recalling “going through a very emotional and difficult time that’s obviously something that I never dreamed would happen to me.” He figures Richardson will face a similar experience.

“So much of what I go through personally goes into my music, but for me, that’s almost a form of therapy,” says Rogers, who started writing at 12. “I also know that, unfortunately, I’m not the only person who has gone through a divorce. And I think people hearing the fact that they’re not the only one, it’s a comforting thing, and that’s what music does for me; when I look for songs that I can relate to, it’s always about some form of making me feel like I’m not the only one. Or making me feel like it’s gonna be OK.

“I don’t wish a divorce on my worst enemy, to be honest, but life goes on and we’ve got a beautiful, healthy little baby out of it, and we’ll just continue to raise her and love her,” says Rogers of his daughter, Isabelle, nearly 3. “It’s the first time I’ve talked to anybody about it; it’s something that still is pretty fresh for me to talk about. But it’s in the songs and it’s on the record, and I feel like there’s no bullshit when it comes to songwriting.”

With a laugh, he adds, “So I couldn’t help but write a few songs about it.”

Black says the band has built a career performing songs about love and loss. And for Hill, that’s not a problem, “as long as the songs are heartfelt and true.”

“Music is there to evoke an emotion, whether it be funny, happy or sad,” he observes.

Richardson says his experience made him thankful he has his music, and good friends who helped him get through it.

The band’s last remaining single guy, he finally got engaged around Christmas — which raises the issue of whether heading into marriage after watching Roger’s union fracture gave him pause.

“Nobody’s perfect. Everybody makes mistakes,” Richardson says simply. “Me and my fiancé, we’ve known each other for some time. We were actually friends before we ever started dating. I feel real confident about it. Just because somebody else’s situation doesn’t work out doesn’t discourage me. On the other hand, you can look at our guitar player, who’s married to the same girl that he was with in high school. Sometimes it works out for people and sometimes it doesn’t, but you still gotta try your hand at it.”

That sounds like the kind of advice Finlay would give. And the guys in the Randy Rogers Band have been living with that “go forth” mentality since Rogers drew that now-legendary line in the sand so many years ago. When he asked his bandmates to step across it if they were in it for the long haul, each one did, and a dozen years in, they’re still making music with as much honesty as they can.

“You can’t fool anybody when you’re onstage,” Rogers says. “People can see if someone’s up there for themselves or they’re there because they love what they do. I hope people tell that from our shows, that we’re all in this because we really can’t do anything else. It’s what we chose to be our life’s work. It means more to us than a paycheck. There’s a spiritual thing goin’ on with it and there’s definitely an emotional thing goin’ on with it. And if you can convey those two things onstage, that goes a long way with people. I think I had that when I started out with Kent playing those open-mic nights, and I could tell that Kent also had that about him, that he was a lifer and was in it for the right reasons. I think that’s probably why he and I hit it off.”

Maybe his wedding ring’s gone, but Rogers’ musical marriages are more solid than ever. And he still plays at Cheatham Street, the place where he and his bandmates dared to dream, then cemented their vows.

No Comment