By Holly Gleason

I was wearing brand new Prada velvet Mary Janes, with saddle leather straps, and a big velvet, men’s cut shirt from back in the late ’80s, when I was first in L.A., trying to be a baby rock critic of merit. The shirt was one of the few nice things I owned back then, and I cherished it; sliding into it with banged-up jeans and forest green cowboy boots, a little bit of luxe boheme splendor for a girl living on a lotta ramen.

It seems somehow right to have been dressed like this today when I got a text that read, “Is Leon Russell someone you feel you could write a passionate tribute to?” Reading it, figuring this was a pro-active editor looking to stay ahead of the bodystack the last couple years has turned into, I innocently replied, “Yes, why? He hasn’t died, has he?”

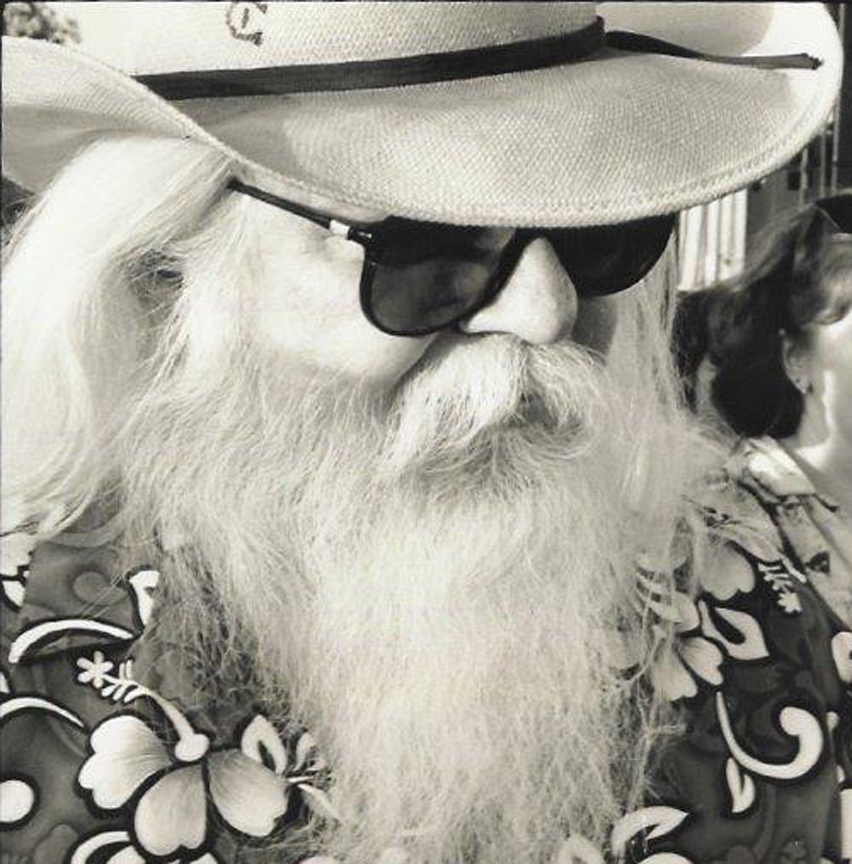

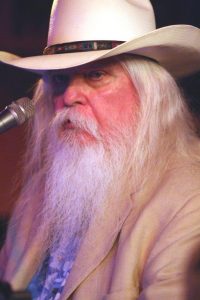

But, of course, he had. Hand in the air, I asked for and paid the check, purse flying to my shoulder, soles to the sidewalk. Leon Russell, always sort of fragile, always incandescent like a candle flame. He was never quite a hippie, nor a gypsy, nor a field preacher, yet somehow he embodied all, and so much more.

Men like Leon don’t really die, maybe shimmer a bit and fade a touch. But dead? C’est impossible. Except the Google Seach confirms – even Fox News says so. And once again, here I am, dizzy from the loss, torn from the moments and music surrendered to the sky.

I can’t even remember the first time I saw him; probably on the great equalizer of humanity, music and social consciousness – and my father’s favorite – The Johnny Cash Show. All I know is my mother snarled, as only she could, “He looks high …” at the TV set in their bedroom — and I truly thought Santa Claus had made good on that summer of love promise to “Tune in, turn on and drop out.”

There he was at a shiny black grand piano, silvery cascades of hair pouring down like white waters, eyes behind mirrored aviator shades as his hands kept rolling and pumping over the keys like some kind of baker making kolaches or other kneaded and twisted delight. He had a voice like an old dog lifted in protest, but there was a zestiness to it, too. You just wanted to taste what he knew — and I was far too young to even imagine.

But I wanted; oh yes, I wanted to know.

Leon Russell invaded my school car, too. The disembodied voice, wrung out and twisting, floated over the vinyl bench seats. The jaunty “Tight Rope,” all carny and “hey, y’all, watch this” and the arpeggiated “A Song For You,” which pledged of loving someone “beyond this space and time” — and because it was Cleveland, the rock ’n’ roll capitol of the world, yes, Russell’s version spun on the rock station in defense of the man who wrote the Carpenters’ inescapable rendition on every pop, ac and elevator music station on the dial.

There was “This Masquerade” for George Benson, “Delta Lady” for Joe Cocker, “Superstar” for the Carpenters. And there were the conversations my hippie babies would have about Mad Dogs & Englishmen, miscegenation (I couldn’t spell it, so I couldn’t look it up back then) and Mary Russell, about Concerts for Bangladesh, records with Willie Nelson and being a genius.

I still thought he looked like Naughty Santa, too much fun and treats and music. I didn’t know about the years in Los Angeles, working with Phil Spector or producing Bob Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” Nor was I aware that it was Russell’s Shelter Records, partnered with the producer Denny Cordell, that was soon to toss the terse raw rock/punk of Tom Petty and the fist-in-your-face “Refugee” into my world. And I didn’t care. Just knowing someone like him existed was plenty.

It was during my tenure as a freelancer in the mid-80s working the country and black music beats for The Miami Herald that the competitive paper’s Jon Marlowe called me to meet him in the stairwell. Stringy white hair, motocross jacket when no one wore such things, The Miami News’ sole critic would cackle and tell me what I was missing; treating me like a colleague, though I was mostly starry-eyed kid.

“You have to pay attention to Leon Russell,” he advised. “As important as Dr. John for mainstreaming that New Orleans shuffle, but a much wider hoop — he’s gospel, and rock ’n’ roll, and soul. And he doesn’t flinch or pander. They can’t make him commit to a box, so they act like he’s some bit of fringe of an Indian jacket. You dig in, you’ll see.”

So out to the Hialeah swap meet I went. Nickels and quarters and dimes. A few bucks could fill in the gaps back then, bad cassettes and slightly blemished vinyl. But the content was there, and man, “Stranger in a Strange Land” was an existential question that suited my own no-man’s-land existence; “Roll Away the Stone” took the metaphysical promises of my Catholic Easter and sowed them with a fiery promise; and the spongy strip-house piano of “Roller Derby” rubbed the undercarriage of the seemingly innocent enough. All of them were bolstered by a peacock feather fan of brash female background singers, equal parts streetwalking working girl and street-smart seraph. Divine and dirty, glorious and porous all at once.

If I got The Band and the power of “Cripple Creek” and Music From Big Pink … If I thought I was figuring out C&W’s bastard Byrds/Burrito’s children Sweetheart of the Rodeo and The Gilded Palace of Sin … If I believed in the mellifluous tone of the steel guitar rising off those Poco records … Then this was the grittier, funk on the roots cornerstone to whatever those other acts were scratching away at.

It’s the reason Eric Clapton, the Stones, and Dylan embraced his musical touch — and why Jerry Lee Lewis took a young Russell and his pals out as his back-up band on a two month tour. To have the kinetic charge to serve as the Killer’s band, you gotta know the inside out from the ground up.

And so, I had my own kinda sphinx: behind mirrored shades, in crisp white suits, playing hillbilly music under the nom du chanson Hank Wilson and wearing a top hat or Stetson like some kind of real world crown. When I felt down, his records were like tapping a vein; Leon Russell & the Shelter People offered a soundtrack for a dreamer’s diaspora. Promises of home and redemption, songs of raw ache and utter brio, guitar notes twisting and piano thump-thumping like a strong heart taking pleasure, it wrung out my own young angst and hung it on the line to dry in the bright light of the sun.

But Leon Russell, like so many of the ones who came before, seemed elusive. Like the scent of Nag Champa, it is in the air, but impossible to touch: sweet, spicy, sense-piquing, yet ever ephemeral. He was always in the back hallways and fire escapes of my life and times in L.A, when FAX machines were super-high tech and Tower Records was almost a city block of sheer heaven. But you don’t meet men like Leon Russell, because visionaries — even those born and based in Tulsa, Oklahoma — just don’t exist among mere mortals. So just the notion is plenty as life whips by and stacks up at your door like so much chord wood for the winter.

Until ex-fiancée No. 4 said “Let’s go to dinner, let’s go to 12th & Porter …”

He had that naughty twinkle in his eyes, the one that always promised too much fun and plain adventure. I probably put on something velvet with my banged-up Levis, probably pulled on cowboy boots of some sort, wiping my mouth with whatever bright pink lipstick I was favoring then.

At a table on the black and white squared linoleum floor, with a perfect view through the giant fishbowl front window, I saw the biggest old school Cadillac pull up. It took up the whole view, the rumble of the Detroit muscle almost rattling the glass. It was obviously old school hillbilly royalty pulling up, but here?

I watched as Sherman Halsey, the scion of the country booking Halsey Co. dynasty, whirled from out of nowhere — silky caramel hair tumbling down his shoulders like some sharp dressed Jesus — to open the car door. He reached in and helped a gorgeous black clad arm emerge. My jaw was slack, not even completely knowing what was happening. But by now I understood, it was something — and my thrilled-at-the-secret boyfriend looked like he’d swallowed a 100-watt bulb.

Blinking twice, I saw a large, sturdy yet frail man climb out of the car. With Sherman helping, taking his weight, the gentleman moved slowly, his fingers circling Halsey’s elbow. There was a halo of serious and a cloud of “holy shit” all around him.

Looking at Little Steve, as my fiancée Stephen Charles Hurst was known at our house, I couldn’t find the words. Finally, an “OH. MY. GOD …” sorta tumbled out. “That’s, that’s…”

“Yup, Toots! It sure is,” said my very-satisfied beau. “I thought you’d get a kick out of this …”

And then they were upon us, and my face flushed, and I felt my hand being held by a papery set of fingers, the sinews and pads very apparent. His face was so carved, so lined by life — it felt like a gypsy reading your palm in reverse. You could see the world’s wisdom in the crags and watch its best parts sparkle in his sharp as a hawk’s pupils.

It is rare that I lose conversation, especially when it’s important. I remember the oxygen leaving the room, the temperature feeling hot, myself perhaps a little dizzy. I smiled, perhaps beamed — and I think I spoke a little bit, but am not sure. I just remember how warm and welcoming, kind and familial the elegant gentleman was. He was happy to be out, even on a cane — or was it a walker? — as he knew he’d have to get his hips replaced sooner than later.

He was recording some, trying to figure out the next moves for a creative man who might have been passed by by lesser musical beings. He spoke of Bruce Hornsby, who I knew from the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will The Circle Be Unbroken, Vol. 2, and I believe I spoke of the Virginia-based keyboardist ability to smear genres without losing the musicality. Russell seemed heartened. Men like him, you see, are meant to play.

Working with Sherman Halsey, my fiancée saw Russell quite a bit. He’d come with reports that the rock legend none of my friends would’ve cared about had asked about me. I’d see stardust for days — far more impressed by that than many of the more famous people I worked with. Because those who practice magic get inside you in deeper ways.

Russell didn’t have the comeback with Hornsby that he deserved. Didn’t get the flex that found Levon Helm or Bonnie Raitt. But still he just kept moving forward. No doubt songwriting royalties — and a good musicians union pension for recording with Sinatra on “Strangers In the Night,” plus Bing Crosby, Johnny Mathis, the Ronnettes, Delaney + Bonnie, Joe Cocker, the Beach Boys and many others — kept his bills paid; but there was more fire to him than that. He kept on playing because his passion never quit. That’s why giants like Willie Nelson and Elton John genuflected in his wake, partnering with him for the thrill of trying to keep up and — at least in the case of John’s case — out of the desire to try and shine a little more light Leon’s way. That sparked The Union, the T Bone Burnett-produced John and Russell duet record that put the latter back on the charts for a flash in 2010 — long enough, at least, to help the all-too-often under-recognized living legend into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame the following year. John himself did the honors of inducting his friend, and Russell spoke of how Elton rescued him from a ditch along the side of life’s highway.

But he also had bought a new tour bus, and was about to embark on making a new album with Tommy LiPuma. As I said, music men keep on playing always.

Little Steve and I drifted apart. He found an incredible woman named Shaye, and they’re so much in love, I was glad I could be a way station on his journey to her. We still talk, for what it’s worth, sharing news of Leon or Sherman, ’til Sherman died somewhere in the blur of the last several years. Love that “exists beyond place and time,” you see, isn’t bound by things like rings or marriages — or even death.

Lately, between the election and Leonard Cohen and the death of my own uncle, it feels like life is coming faster and faster; sadder and darker, too. I’ve not had time to pause and reflect, collect and consider — all that has been lost, all that I’ve been blessed to know, to touch, to embrace as part of my life.

Leonard Cohen, truly the ultimate ladies man. Dapper suits, hat cocked just so — and songs redolent of musk and evocation, enough to make a kid’s knees quiver. Like Russell, his gifts transcend the basics of language: he holds much in a few words, scrapes away the sludgy build-up and finds the essential emotion in melodies and imagery.

I remember walking around a corner too fast, returning after a lunch with Don Was, and bouncing into a recording studio just a bit too fast and slightly off balance. The crease in the pewter sharkskin pants could’ve slashed my jugular, if not for the hand that reached out and steadied me. After I was set right, that steadying hand extended and a low voice announced, “I’m Leonard.” With dark cocoa eyes boring into me, I gulped. And stared. “And you are?” Again, stammering, I managed to get my name out as Don Was laughed and Sweet Pea Atkinson took it in with a guttural chuckle.

That’s the thing about the Towers of Song, they don’t have to flex. They just need to be. The poetry of who they are permeates everything, ignites songs with the right amounts of reserve and tension or raw desire and hell raising. For each, the way they walked or looked into your eyes was as profound as the songs they wrote.

And whether people realize who these non-attention seekers were, their songs live on. Cohen’s “Hallelujah” has been recorded — like Russell’s “A Song for You” — well over 100 times. Each has their cannon, each has their own special stew; but both created an image, a sonic template, even a place within the times that solidly maintained their reality.

“Shoot Out on the Plantation” is playing as I type this. As the nation is torn in half by what they think is unthinkable, it’s all here in this song. With the chunky funky beat, the sticks moving across the high hats and clanging on cymbals with the pace that says, “We mean business,” Russell suggests the upside-down reality of it all: “Yeah, the last one to kiss is the first to shoot / And stabbing your friends is such a drag to boot …”

Chasing the dream, the song, the money to pay the rent or the rush to keep on going, there is a restlessness inside the creative that never truly goes out. If Ray Charles won a Grammy in 1993 for his version of “Song for You,” this could be anyone’s refrain who plays the game of plying music for other people to find their truth.

I’ve been so many places in my life and time

I’ve sung a lot of songs, I’ve made some bad rhymes

I’ve acted out my life in stages, with ten thousand people watching

But we’re alone now and I’m singing this song for you

As a woman who’s chased the road and gently blown on the kindling fire of dreams built on stages and studios, the fragility and need is something I’ve witnessed and felt my own damn self. When it’s late and lonely, you wonder about the cost … and you hum a song, and hope that the price is worth what you’ve paid. But you know, you never know. You really can’t, a because the rush of when it’s working is so intense — and because the emptiness of doubt and being all alone can’t truly be measured. Somewhere in between, there’s a lot of boredom and the baseball cards of dreams. You flip ’em over and remember how sweet it was, waiting on the next song to come up on random rotation that takes you back …

According to news reports and the official statement issued by his wife, Russell — who’d already survived a massive cardiac event and major brain surgery, went in his sleep. He was 74, at home in Nashville.

Leon Russell was a man who loved and kept it funky, whose humanity was pervasive and reached far beyond those who knew about the Tulsa Scene, who warmed their haunted places with Carney or Americana or Leon Live. And now, somewhere, Leon’s looking down, fingers spread like sunrays as he surveys all he left behind. The gris gris and the juju is ours to keep alive, and the songs, well — the songs are here for all to love and live inside. Funny, too, how a man who can find the magic in “He Stopped Lovin’ Her Today” and “Rollin’ in My Sweet Baby’s Arms,” as well as “I Put A Spell on You” and the live combust of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” merged with “Youngblood,” would write his own elegy almost half a century ago.

For all its need and ache, the larger truth in “A Song for You” comes now. As the piano rises and falls, the lyrics open wide to hold us in their embrace now that he’s gone. Gentle catch and benediction, it seems Russell had already spelled it out; it’s just we were all too pinwheel-eyed to believe this moment would ever come.

I love you in a place where there’s no space or time

I love you for my life, because you’re a friend of mine

And when my life is over, remember when we were together

We were alone and I was singing my song for you.

Like all the real hippies, he didn’t fear death — or heaven. He shook his songs, plied his guitars and piano, mined the chutes of Dixie, swamp, Appalachia, Tulsa and tumbleweeds to conjure that sound that shook its tail and balmed the wild night. When America stood at a crossroad, Russell emerged saying, “Why not merge it all?”

Uptopian. Idyllic. Hopeful. Impossible. It was who he was, and all that existed in his music from the very beginning. For a young man who started out Claude Russell Bridges and morphed into Leon Russell by virtue of a fake ID to play in L.A. clubs, it doesn’t matter. Only the music, and how it lifts us up.

For me, trying to make sense of everything, I’m gonna try to let it do that. And it’s funny, I’ve not been around Mr. Russell — except at random airport gates on flights in and out of 6-1-5 — in years; but the idea that he’s gone still guts me somehow, lays me open wide. Maybe it’s for those days when I was young, and he was some kind of earthy paternal presence of us all. Or maybe just like Leonard Cohen and David Gleason, there are some who seem as if they’re inextinguishable no matter what.

With the candles lit and day still blazing, I think I need to walk it off. Find a park or trail, touch the bark and hum just a little bit. He ain’t coming back, but perhaps in the songs, I can hold that smile and white-white hand with the knuckles protruding just a little in my soul again.

Thank you Holly, my goodness what beauty, you captured a lot of my experience as well. I grew up in Oklahoma and lived (live) in Tulsa as a young adult. So he was forever popping in and out of my life just being a Tulsan. Saw him at the Brady Theatre at his Birthday Bash. 3 years ago. And got to see his new Bus! He is our Oklahoma son and I am so lucky to have been here to catch dashing views

of him throughout the years. Thank you Holly, you captured a part of him that i’ve not read elsewhere.

Lovely piece Holly.

Beautiful tribute, Holly. This first-person account brings with it a heartfelt authenticity not found in most memorial tributes, and captures Russell’s essence as well as his history. Thank you for this. 2016 has been a rough year for the arts.

This article is some kind of wonderful. It brought tears to my eyes. Knowing how many people miss him desparately.is a comfort to me. I didn’t know him but I was always,a fan since I heard Tight Rope.

Thanks for the awesome tribute. It brought tears to my eyes. We,.his fans, miss him so much.