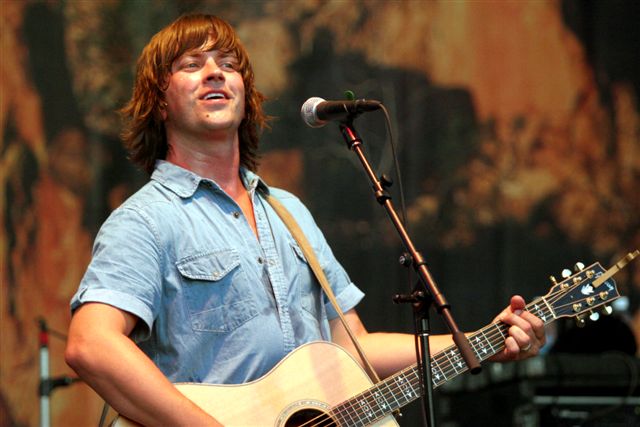

By Richard Skanse

(LSM May/June 2014/vol. 7 – issue 3)

“We’ve been doing this longer than you’ve been alive …”

So begins the first song on the Old 97’s 10th studio album, Most Messed Up, and if you’re not a fan of songs that shamelessly get self-referential — let alone veteran rock ’n’ roll bands that refuse to quietly move aside after 20 good years to respectfully make room for new kids half their age, well … step off the tracks. True to its name, Most Messed Up crashes through the door three sheets to the wind and dead-set on finding not just a hook-up or punch-up but a dozen rounds of each. The four 97’s (singer/ guitarist Rhett Miller, bassist/singer Murry Hammond, lead guitarist Ken Bethea, and drummer Phillip Peeples) may all be a lot older than they were when they first rolled out of Dallas with their 1994 debut, Hitchhike to Rhome, but not even their salad days as Bloodshot Records-certified, major-label-bidding- war-provoking insurgent country upstarts found them ever sounding quite this full-tilt and go-for-broke on record. It’s the sound, Miller admits, of a band that still very much has something to prove.

“I’ve always been grateful in a way that there was no massive success that came along, because the hunger that propelled me when I was 15 years old and doing my first gig has never gone away,” says Miller, calling from his home in New York’s Hudson Valley a day before reconvening with the rest of the band to kick off a four-month tour. “You’re always trying to prove it to somebody, whoever that is — like the cool kids, or when I was young, the girls — and I’ve always felt that and I’ve always liked that. I like the drive and the ambition. And yes, I always want to be better and be the best songwriter that I can be, and I want people to recognize that, too. I know that there’s something gross about saying it, but there’s a reason I get up onstage and try so fucking hard every night, and that’s that I want them to get it.

“I don’t want to spend my life apologizing for, you know, trying to be a kick-ass rock ’n’ roller,” he continues. “Because I think there’s something noble about spending your life in pursuit of that, and I’m proud of it.”

Doubtless the rest of Old 97’s would concur, and the performances on Most Messed Up certainly back that up. But it’s part of Miller’s job to talk the talk, and he’s acquitted himself so well in his role as frontman, principal songwriter and band spokesperson that the rest of the group has long since come to terms with his occasional need to pop out for a solo album every now and then. He’s a trooper, too: At this year’s South By Southwest Music Conference and Festival, Miller trekked down to Austin for a week’s worth of Old 97’s promo work all by his lonesome. When we catch up with him a week later, he’s still recovering — but nevertheless ready to hit the road again in 24-hours and get back to the business of walking the walk.

You were just back in Texas for SXSW, but you were the only Old 97 here all week. How many frontman-get-out-of- jail cards did you earn by handling all of the band’s SXSW promotional duties yourself this year?

[Laughs] Man … my manager just called me to thank me again for all the hard work or whatever. But I like to work. So if I have to go down there and leave the family, I’m fine with working my ass off. But boy, it kicked my ass this year. I had like seven gigs in 48 hours, and then the panel I did and two interviews and two photo shoots … it was really a lot. And when I got back I was sick for 48 hours, just with a cold and from being run down. So I had to sleep for like 15 hours just to recover. But that’s fine. Like I said, I love to work.

You were born in Austin and grew up in Dallas, but home for you now is in upstate New York. How did you end up there?

My wife and I were in L.A. when we figured out we were going to have a kid, and we just couldn’t really justify staying there because we couldn’t afford anything we would have wanted. And we ended up really loving it here. We live outside of a little college town 90 minutes north of Manhattan, and it’s unexpectedly a beautiful place to live. Although I do miss Texas.

You’re a long way from the rest of the Old 97’s, who are kind of scattered over the rest of the country: Ken and Phillip are still in Dallas, but Murry lives out in California, right?

Yeah, Murry lives in Pasadena, and Ken and Phillip are in Lake Highland.

Do you think the fact that you all live so far apart has actually been a factor in why they Old 97’s have stayed together for so long? Would the band still be together if you all lived in the same town all the time?

[Laughs] No, I think you have a good point. I think when we come together, we’re really together, and when we’re apart … we don’t need to be together. I think there’s something nice to that. It takes some of the pressure off. It’s like when I do a solo record and I tour behind it a lot and I really get to where I miss the guys and I’m so happy to get to come back and make a record with them. And then by the time we’ve made an Old 97’s record and toured the record and done all the work for that, I’m really ready to go back to the solo stuff for a little bit. So yeah, I think your point is a good one — absence makes the heart grow fonder.

When you’re in the middle of making a solo record — obviously you’re not all by yourself, but do you ever consciously miss the guys? Like, “Hey Murry, listen to this! Oh, wait …”

Like the phantom pains kind of a thing? Yeah. You know, there’s a thing that happens that’s kind of like that. After finishing the Old 97’s record at the beginning of the year I went straight to Portland to start work on a solo record with Chris Funk and his band, Black Prairie, which is most of the Decemberists plus a couple of other players. And there were some contentious moments at the end of the 97’s record, like there is in any democracy — there was some back and forth that was really heated. And so I got to this session in Portland with these other guys, and it was just so easy going because we didn’t have all the baggage that 20 years of history can sometimes bring — and because I got to be the boss. There were a few moments where I thought to myself, “Oh, I want to do this … I wonder how I’m going to convince them?” And then I thought, “Oh yeah, I don’t have to convince anybody of anything, I just have to ask them nicely and then they do it!” So not to say it’s better or worse, but it is different. But the 97’s wouldn’t have a 20-year catalog that’s as loved as it apparently is if it wasn’t for that push and pull dynamic that makes us what we are.

Speaking of that push and pull, have there been times over the course of the band’s history when the 97’s really did feel up against the ropes or about to implode? Have you ever come that close to calling it a day?

I’m such an optimist that I’ve never given into the fear or awareness of any proximity to an implosion. But in retrospect, I know that there were times, like in the early days of the band — like there is in any band — where you’re wondering if this thing was going to work. And then you look at your friends who have jobs and who are making actual money and have some security. So I would bet that there were a few moments where we could have easily given up. But at the same time, things really kept moving; we did the Dallas record, then we did the Bloodshot record, and we went straight from that to the bidding war with all the labels trying to give us as much money as possible to get us to sign with them. And from that straight to, you know, we had a pretty glorious three-year run on Elektra where they were spending a ton of money to get people to know about our band, which was fantastic — although in retrospect I can see how that business model failed. You don’t need $300,000 to make a record — come on! But all of those years moved pretty quickly, and there wasn’t a lot of time for second-guessing. And there wasn’t a lot to be unhappy about. We were quickly moving into the position of being basically as successful as the level of bands that we had all looked up to and emulated, like X and the Pixies. Maybe we never played arenas like the Clash did, but you know, they were opening for the Rolling Stones, so whatever. We kind of pretty quickly got to the point that we had all wanted to be at.

After that, the next time that kind of offered a lot of opportunity for disaster was when Elektra was folding, and I had decided to make a solo record. That had nothing to do with me wanting to become a famous pop star, which of course I got accused of a lot at the time; it was really just that I had all these songs that the band didn’t like, and it was making me fucking crazy that I couldn’t release them anywhere. I didn’t see it as being an either/or; I thought, I can do this and that, and the fans will hear the record and realize, “Oh yeah, these aren’t Old 97’s songs, this makes sense.” And honestly, I think that’s how it’s worked it out. But there was a time when I was making The Instigator and all the changes were happening when I think we could have stopped being a band. I think there was some fear and bad feelings going around. But in the end we just came together and said, “If we can get over this, we can be a band for fucking ever. We can be 70 years old and still be doing this and people will still be wanting to hear us, if we do it right.” And fortunately I think we did it right.

The Old 97’s album Drag It Up came out right after The Instigator. Was that the band’s therapy record?

Yeah, Drag It Up was where we really sort of worked through those growing pains. And I can still hear all of that when I listen to it. There are some fun moments on that record — I’m really proud of “Won’t Be Home No More,” and I think “The New Kid” had some elements of triumph about it — but that’s a tough record. It was a tough record to make, and sometimes it’s a tough record to listen to. But I’m glad we made it; you know, you’ve gotta make it to go onto the next one.

I think that “next one,” 2008’s Blame It On Gravity, really did convey a much more positive head space for the band as a whole, and a couple years after that y’all had so much new material to work with that The Grand Theatre ended up being two albums (Volume I in 2010 and Volume II in 2011). But to my ears, Most Messed Up sounds like the most assertive and energetic record you’ve ever made. And it’s also probably the most reckless sounding — like the Old 97’s on a bender. What sparked that attitude about it?

That’s a good question. I’m not positive I have a full answer for it. You know, in terms of the songs, the song “Nashville” is the one that kind of opened the floodgates with these themes. And that was a fluke. I’d gotten put together with this old songwriter in Nashville, John McElroy, and he said, “I think your audience would like it if you walked out onstage and said ‘fuck.’” And we got wasted at 10 a.m. at his house in Nashville and wrote this song in two hours. And it’s funny because out of all the songs on the record it’s got the most narrative voice; it’s the most removed, kind of like a short story. But it really opened me up to the idea that I don’t have to be subtle or hide behind anything, that I can just walk out onstage and go, “Fuck it, I’m going to be honest — all the stuff that I only alluded to on all the other records, I’m going to just fucking stand up and sing it; I don’t have to be embarrassed. This is real life, we’re all grownups here.” And that was really liberating, knowing that I can be as fucked-up as I want and that I don’t have to pretend to be great, and if the songs are raw and I let myself go there, then it’s probably going to be better than if I try to do something fancy and hide behind something else.

That said, though, it doesn’t mean that all the songs are straight-up autobiography. I’m probably a little bit better off than the guy on that album. But it’s definitely me.

So it’s not necessarily a personal mid-life crisis being worked out there.

Well, a little bit. I mean, everybody I know is going through the shit; it’s part of being in your early 40s and realizing that the sweet bird of youth has not only taken off, but flown away to somebody else.

I think my favorite line on the record is “I’m not crazy about songs that get self-referential,” from “Longer Than You’ve Been Alive” — a song that is unabashedly as self-referential as any you’ve ever written. But I also always loved “The One” from Blame It On Gravity. I just think it’s fun when you kind of name- check the other guys in the band.

[Laughs] Yeah, or when my friend Robert will end up in songs. The reason I think I wrote that line is because I heard an echo of my friend Jon Brion’s voice, who produced The Instigator for me, and who’s somebody I really admire as a songwriter and as a producer and as a person. When we were making The Instigator, I had a song called “This Is What I Do,” and it was pretty self referential, too. I actually named girlfriends from my past by name. And Jon said, “I like this song, but in general, I really don’t like songs that are self referential. I think it sort of kills some of the potential for universality of a song if you make it specific about yourself.” And I’ve always worried about that a little, and it’s kind of nagged me as I’ve written songs in the 12 years since then. But part of this record, and that song in particular, was, fuck it — there’s no rules. And if I want to sing about being in a rock band for the last 20 years, I’m going to sing about it, and I’m going to tell the truth. So when we play that song live now, I’ll sing that line, “I’m not crazy about songs that get self-referential,” and then I’ll say, “Too late!”

One of my other favorite songs on the album is “Intervention,” which features a guest appearance by Tommy Stinson of the Replacements (and more recently, Guns n’ Roses). How did that come about?

Tommy was there for the basic tracking of the final two songs on the record, which were “Intervention” and “Most Messed Up.” And then he plays additional guitar on three other songs, too. But one of the most fun things he did was … Tommy’s not the world’s greatest singer, per se, but there’s a lot of fun background vocals and yelling that he does, especially on “Intervention.” We were trying to do some banter at the end of the song where the guy who’s going through the intervention would say, like, “Give me back my beer!” or, “I’m not that bad, I can stop any time,” that kind of thing. And at the very end of the song, Tommy says something that I don’t even know what the fuck he’s even talking about, I think maybe it’s a drug dealer reference or something, but he says, “You got … you got Huggy Bear’s wallet phone number?”[Laughs]

It’s so perfect. And his voice is so distinctive. I like Tommy a lot. He actually had a lot to do, I think, with this record being all sloppy and raw and as unapologetically rock ’n’ roll as it is.

How long have you known him?

Tommy and I did a charity event in Philadelphia about five or six years ago, and we stayed in touch. We just hit it off. We stayed up all night long that night, and I actually bragged about it for a couple of years that I had to carry him and his wife at the time to their hotel room and pour them into their bed — that I’d matched him shot for shot and whatever. And then sure enough, when he came to Dallas when we were doing pre-production for this record, I stayed up thinking that I could match him again, and wound up falling down and breaking my elbow in the hotel room afterwards. So, thanks a lot Tommy! But I guess the moral of the story is, no matter what you think, you can never out-drink Tommy Stinson. So don’t even try.

I think it’s a trip that he’s been in Guns n’ Roses now for almost as long as Slash ever was.

Well he’s been in Guns n’ Roses longer than he was in the ‘Mats! Which is crazy.

You did another interview recently where you talked about Tommy inviting you out to catch a GNR show in Dallas and hang out with the band afterwards. Did you actually meet Axl Rose?

I saw Axl through an open dressing room door, and he was wearing a mumu and getting a foot rub from a small Asian woman. But I was not invited to meet him.

I’m actually an Axl defender and a still a big GNR fan, but that image of him sounds about right.

[Laughs] Yeah. It was a pretty good show, though. If you’ve seen them play recently, you’ve probably noticed that he has other people sing a bunch of songs, which gets a little old. But it was a pretty good show anyway.

I’ve noticed that on past records, the one or two songs that Murry sings and writes kind of stand out from yours, style wise — almost like interludes. But his song “The Ex of All You See” on Most Messed Up seems very much in the same vein as your songs on the record. Did he write it to match the mood or did it just happen to fit?

Murry brought a handful of really beautiful songs to the table, and if we had made a different record, I could imagine at least two or three Murry songs on the record. But when this record was sort of taking shape, he came to us and said, “Look, this record is so tight, and so conceptual in a way, that I don’t really see a bunch of my songs fitting on it. I just see this one song that would really make it rock.” Because he hasn’t had just one song on a record I don’t think since maybe our very first record. But that was his choice; he just really wanted this record to be what it is, a really tight, sort of high-concept thing, and he didn’t want to take it away so we would have to bring it back … I think he just wanted to maximize the punch of the message of the other songs on the record. Which is a testament again to how long we’ve been together and how the egos have kind of all mellowed a little. We’re like a little army, man, roaming around the country.

Were the sessions for Most Messed Up radically different from the ones for The Grand Theatre?

They were not radically different, because we were in the same studio withthe same producer (Salim Nourallah), and we did kind of the same thing, where we did some pre-production to work out the songs so that we could go in and cut them basically live off the floor. But we did it moreso than we did onThe Grand Theatre. On The Grand Theatre, we really left a lot of room for tons of overdubs, and I ended up having to re-sing a bunch of stuff. On this record, most of what you hear was cut live as we recorded to tape. Almost every single line of mine, and a lot of Ken’s guitar, too, and the whole rhythm section. And the imperfections are one of my favorite things about the record. I’m so sickened by the way music’s become this really clean, perfect sounding thing. Where’s the humanity in that? I’m sort of afraid for the future of music, because kids are going to listen to it and go, “ugh, why would I want to be part of something that a machine can do? Why would I devote my life to it?”

Looking back at The Grand Theatre — not to nitpick, but I was always disappointed that you didn’t just release all the songs from those sessions as a big “screw-it” double album, all at once, instead of in two installments. Was that ever the plan?

Yeah. Well, I wanted it to be a double album. I wanted it to be the whole big, commercial disaster, but New West Records apparently was trying to make money. Which is fine — I can’t begrudge them that. And in the end, it was good that we spread it out, because with The Grand Theatre Volume Two, some new songs came in and the songs that we had got a lot better. So it wouldn’t have been as fully realized if we had done it all at once. But yeah, I for sure wanted to do the double album.

You mentioned New West. You’re now with ATO, which I believe is the Old 97’s fifth label. Is there always a period of playing catch-up when you sign with a new label, just to bring everyone there up to speed? Does it feel like starting over?

I would say that so far it’s been easy and good. I don’t know if it’s more work for our manager … it probably is, but that’s good — they should earn their money! But I never had to do it so much. The Elektra to New West switch was really easy and painless, and we had some good years with them, and I still have some good friends at that label and there were no hard feelings at all. They were great. But it did make sense to switch for us, and I don’t think we could have picked a better label than ATO, with the way it skews toward youthful and rocking. We’re not ready to be an old-timey band. We’re not ready to make easy going, back porch, toe-tapping alt-country. In a way, I don’t know if it would be better for our career if we were; maybe oldsters are a better market for us to try and plumb. But, whatever. I love the roster ATO’s got, I love the people at the label, and it feels like such a perfect fit for us.

So I know you’re not looking to call it quits anytime soon, but this being the band’s 20th anniversary, is there any one moment in the Old 97’s history that stands out as a personal favorite?

Gosh. It’s funny, but I think my lack of nostalgia has probably helped in my career. I mean, it’s such a lame answer to say that it’s always the new record that’s the thing that I’m most excited about. But in the case of this record, I’m more excited even than usual. When we got back the masters for this record and I realized how successful we had been in translating these songs into this sort of statement of purpose, and how unlikely it is, for a band without massive success, to be able to do it for this long … that’s a huge feeling of accomplishment. And I take a great deal of pride in what we do. And then lately there’s been some moments of validation, critically and from my peers, and I feel good about right now, and I feel good about the future. For the last, I’d say five or 10 years, I’ve been really aware of the long game in a way that I hadn’t been before. I know that I would like to be the kind of songwriter that, you know, like right now, I want the 20 year olds to look up to and go, “I want to do that, I want to be able to do this for 20 years and still make good records.” And I look at Willie Nelson or Kris Kristofferson, and I think, I want to be that: I want to be that guy that people look up to when I’m an elder statesman and say, “He did it right.”

That kind of sounds an awful lot like Matthew McConaughey’s Oscar speech.

[Laughs] Yeah — I’m chasing myself! But I do feel pretty good about things right now. Knock wood … I’m about to be on tour for four straight months, so we’ll see how I feel after that.

No Comment