By Chris Mosser

(LSM Jan/Feb 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 1)

Texas music is a unique beast. We are blessed to enjoy and take part in a vibrant and economically viable regional music scene all our own, bolstered by strong talent and storied venues, radio stations, TV programs, magazines, websites, record stores, and, last but by no means least, thousands of passionate, loyal fans. But sometimes that unbridled enthusiasm can sting, because some of the scene’s most hardcore fans will turn on an artist on a dime the moment they appear to be growing too big for their britches — that is, dare to dream of taking their career to the next level. A Texas artist selling out Billy Bob’s is cause for celebration, but a Texas artist moving up to the “big leagues” of Nashville is more often than not branded a “sellout.” There’s perhaps no single Texas artist who has encountered this reaction more famously and publicly than Pat Green.

While Texas country music can be traced all the way back to Bob Wills (and even further, if you want to get academic about it), the hugely popular scene as we know it today was sparked in large part by the aspirations of Green and fellow Texas Tech student Cory Morrow back in the mid-90s. Following in the footsteps of their heroes — Robert Earl Keen, Jerry Jeff Walker, Willie Nelson, Joe Ely and others — they began singing their own songs about Texas and dancehalls, graduating from Lubbock bars and frat parties to headlining the biggest outdoor festivals in the state. The mainstream music machine in Nashville, never blind to a potential profit, saw cash in the crowds and snapped Green up early last decade, producing the modern Texas music scene’s first bona-fide star. For Green, his dreams had come true, but the way forward would prove treacherous.

Green’s 2001 major-label debut, Three Days, measured up from both a quality standpoint and that of Texas legitimacy back home; with it, the enduring Green concert staples “Three Days,” “Take Me Out to a Dancehall” and “Southbound 35” took the Texas sound to a national audience. But the rest of his output over the ensuing decade, while selling respectably and producing a handful of country radio hits, managed to alienate the more purist elements of the Pat camp back in Texas with its increasingly glossy, “pro” production. The farther away Green seemed to stray from his gritty DIY roots, the more his less forgiving early fans back home dismissed him as a wayward prodigal son rather than cheer him as a triumphant ambassador of Texas music.

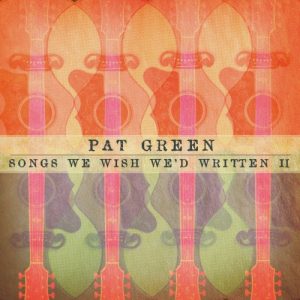

In the last couple of years, a battle-tested, older and wiser Green has returned to his native Texas, making his home in the Dallas area, just a piece up the same interstate highway he’s celebrated in song from his boyhood home of Waco. After a decade recording for major labels, he’s signed with the lower-profile but highly respected independent Sugar Hill Records for his next pair of releases. First out of the gate, due Feb. 28, will be Songs We Wish We’d Written II – a new collection of covers modeled after the similarly titled and themed collaboration he recorded with Morrow back in 2001, just before his major-label run. After that will come an as-yet untitled album of new originals that Green plans to wrap up by mid-year. We caught up with Green to chat about his plans via phone in December, in the midst of the proud papa’s busy day dropping his kids off at school.

In the last couple of years, a battle-tested, older and wiser Green has returned to his native Texas, making his home in the Dallas area, just a piece up the same interstate highway he’s celebrated in song from his boyhood home of Waco. After a decade recording for major labels, he’s signed with the lower-profile but highly respected independent Sugar Hill Records for his next pair of releases. First out of the gate, due Feb. 28, will be Songs We Wish We’d Written II – a new collection of covers modeled after the similarly titled and themed collaboration he recorded with Morrow back in 2001, just before his major-label run. After that will come an as-yet untitled album of new originals that Green plans to wrap up by mid-year. We caught up with Green to chat about his plans via phone in December, in the midst of the proud papa’s busy day dropping his kids off at school.

So, I hear from your publicist that you’re runnin’ a little late because you’ve been runnin’ kids around today. Tell me about balancing daddyhood with crazy musician life.

I tell you, I think it’s getting more difficult. I don’t think that’s a surprise but I didn’t know how difficult it was going to be emotionally. I think it’s human nature to want to be around your family and your children — especially, you know, if you happen to like them! I really just, I enjoy my children. You know, last night it was the campout in the bedroom; we built the fort with the sheets hung from the bedposts and all that, we watched a Santa Claus show … that’s what you miss, those moments where you’re totally with ’em. When you’re on the road away from the house, you’re thinking, you could be doing that. So that’s the hard part.

What sort of road runs do you expect to be doing in the near future: the long, multi-week tours or the shorter runs?

I stopped doing the real long stuff years ago, right after I left RCA — and all things really Nashville — a few years ago. At that point, I was like, you know, I don’t have to go out there and beat my head against the wall. I can do just as good business-wise being smart as I can being out there just to be out there. The long tours can be fun, but often they don’t really make your career go much further, and they often also end up losing money. I’ve learned how to be a smarter business person, and it can be hard to view music as a business — I think that’s why they call it “show-biz” — but anyway, we streamlined the touring process a few years ago, and the most we’ll be out at a stretch is around 10 days.

So with limiting the long runs, is there also a feeling that you’re happy with the playing field you’ve established?

Well, even though I didn’t become George Strait, I got as close to that as you can, and what I notice about being at the top of the pile, or close to it, is that people start taking shots at you. The vast majority want to see people succeed, but there’s another group out there who can’t stand the establishment and will take very public pot shots at you. These same people will say all kinds of positive things about people on their way up, but with someone who has achieved a certain level …

You’ve been a major target for that kind of thing.

But I’ve noticed that it’s only the negative energy that tries to go public. The positive energy just kind of sits there, with people who like what you’re doing. You know, I think a lot of people who go mass media just aren’t very positive people, for the most part.

The first new project you have coming out is Songs We Wish We’d Written II, so it makes sense to go back to the first volume, which came out in 2001 but I presume had roots going all the way back to your time in Lubbock, hanging with Cory Morrow.

Yeah! That was great.

That’s a well-worn story that’s approaching the level of lore, so we don’t need to re-tread it really.

[Laughs] Yeah, I’m with you.

But I still want to talk about that record you did together, the first Songs We Wish We’d Written. It’s become very much a seminal, cornerstone album of the genre, and it came out just a few months before your major-label debut, Three Days.

Right. Three Days was more of a collection of songs I had recorded previously, which was the reason we were able to get it out so quickly, because we didn’t have to record much new material.

So with the original Songs We Wish We’d Written, set the stage for me, in relation to where your career was headed. What was the mindset or the goal behind that collaboration? Was it just a buddy project?

Well, as I recall, Cory and I were playing golf at Barton Creek one day, and we got the inkling of the idea out on the golf course, so we went into Jim Bob’s, the bar out there, and had a couple of beers and started writing down what we’d do. So there wasn’t a plan or any unusual goal. At that time, both Cory and I were doing really well. I had attracted a major-label deal, “Carry On” was all over the radio, we were drawing multiple thousands of people to shows in the bigger markets in Texas. So, I felt reasonably confident that whatever Cory and I put out was gonna work.

Sure.

So we both knew Lloyd Maines, we both had bands living in Austin, so we could do this thing for close to zero dollars. There are quite a few songs on that record that got radio airplay and we had strong chart numbers once it was out. We considered it a great success.

So moving from Songs I to Songs II, which in title and intent seems obviously a sequel to that first record …

Right …

It seems that Songs I established sort of an impression of you and Cory as kind of a duo or a team.

Well, I think we were that year, but I don’t know that we’ve done just a whole lot of shows together since then. As far as being friends, we’ve been great friends since Lubbock.

Well, that works hand in hand with what I’m driving at: not so much that you were regular collaborators, but that your personal relationship was well known, and that first record gave the two of you a certain public impression of being tied together, kind of a Yin and Yang, as part of the initial core of the “Texas Music” scene, which at that point was just getting started and has now grown into a much bigger deal.

It sure has, it’s amazing to watch.

So, the big difference, from that perspective with the new record, is that Cory is only in on one song.

Yeah, he’s on one song, and we’ve certainly spoken quite a bit about it. You know, I’ve seen what’s been said on blogs and stuff … I love the conjecture of people who think up outlandish things because they don’t have any information, and they’d rather write something down rather than not at all.

Well, that’s where I wanted to go: How would you answer criticism that would relate to Cory having a lesser role on Songs II than he did on the first record?

I wouldn’t answer it. Cory and I are great friends and love each other, and this is a different project from the first one. I like going to see a sequel of a movie, too, but I think the cliché part of movie sequels is that they’re typically just like the first movie. With Cory and me, it’s just not a situation. We had a brief and understanding conversation about it where we agreed together, both of us, what his involvement would be. We still worked together on this one, but I’ve made more and new friends since 10 years ago, and I wanted with this record, this time around, to introduce songs that a lot of people have never heard. And you know, I wanted to do something quickly, honestly — to get some music out there. Because I hadn’t had anything out in so long, and I’m going into the studio in the next couple of months to record my new record, and I wanted something to be in the works to bring me back out into the public. I’ve been purposefully kind of shying away from the public for a few years, just to get my bearings. I mean, after being, four years on the road 250-days-plus touring with some of the biggest bands in the world, I really just wanted to find out who I was. Scrape off the top level and be me again.

I get that.

Honestly, we recorded the entire record over a total of four days in Austin last year and three or four days in Tyler a couple of months ago. The whole thing went really quick, and there wasn’t just a whole lot of thought behind it, but at the same time, the thought that did go into it was more along the lines of, let’s create something that’s not the first Songs We Wish We’d Written.

I can understand that. It surprises me to hear that this was such a quick project, though, because what I’ve heard so far sounds great. As of now, I’ve only heard two songs off it: “Austin” and “All Just to Get to You.”

I love both of those tunes for sure. Amazing songwriters, both of ’em.

Tell me first about “Austin.” The lyrics, if I didn’t know better and jumped to the conclusion that you had written that one, would seem almost autobiographical, in terms of coming back to Texas or to Austin in particular.

Yeah, I think that’s why the song fits, to be completely frank. That’s a Jon Randall song. Jon and I became friends many years ago, and Jon played it on my bus one night and I was just floored by it, and I told him that if I ever saw that song laying around not doing anything in the next couple of years, I would record it for my next record, and he said, “go for it.” But yeah, it felt great. It said everything I wanted it to say, and you know, I thought it would be a song that people would gravitate towards.

Right on. The other one, Joe Ely’s “All Just to Get to You” — the first thing that jumps to my mind is the common Lubbock connection that you share with Joe.

Sure.

I know you’ve known him for a long time. Tell me about your relationship.

I guess I tend to be a fan of Joe’s first. I watched him do a street dance in Lubbock one time where he did “Me and Billy the Kid,” and that blew me down. And you know, being the opening act, I weaseled my way into backstage a couple of times in those early years, which is how you get to know these guys. Joe was always super cool and kind, and I always thought he had such a great stage persona, I thought he was so much fun to watch, and that’s what really drew me to him. There’s lots of guys I love, but not many of ’em move like Joe moves. Everybody has stolen something from somebody, and I bet Joe got some of those moves from the Clash. He probably stole some of their rock ’n’ roll moves for his show, and I’ve certainly stolen a few of his licks for mine.

[Laughs] That’s great.

Yeah, with “Billy the Kid,” that was such an obvious pick for me, because at the time when I was coming up and Texas music was really young, I felt that accentuating the Texas side, the outlaw side, the cowboy side, was a vital part of capturing an audience that, at the time, had just been whitewashed with the Garth Brooks dimestore-cowboy thing, whatever you wanna call it.

The hat acts.

Yeah, everybody went and bought a hat before the show and became cowboys for a couple of hours. I felt that that was such an authentic song. And then “All Just to Get to You,” that song came out when I was a sophomore in college, I think.

Yeah. Off of his Letter to Laredo album.

Right. And that one also had “Gallo del Cielo,” and that’s another one I considered, because that’s a great song too with a great story; problem is, it’s 14 minutes long and all. But “All Just to Get to You,” with Springsteen singing the backups, that song really meant a whole lot to me when I was in college and learning to play guitar, and starting to become who I became. That particular song was just huge, and now that it’s 20 years old or so, I felt like it’s been given plenty of time to rest.

Cool. How about some others?

One of my favorites is a song that Waylon Payne played for me. Waylon’s been a part of the Texas music scene for a long time, though I don’t think he ever really tried to be, it’s just that he was there. His dad was Jodie Payne, who played in Willie Nelson’s band for a long time, and I met Waylon in Los Angeles at one of Willie’s shows, and I’ve never heard a guy who can sing like he can. And we ended up writing a couple of songs together, and we were signed to the same label for a little while, and we have the same birthday — it’s really kind of a strange thing. But he ended up singing all the harmonies on Wave On Wave, and so we became great buddies through all of that. He has a song called “Jesus On a Greyhound” [by Glen Ballard and Shelby Lynne] on one of his records that I’ve always been blown away by. It tells such a great picture of the way that I see God and Christ working in our lives; a lot of people are looking for the burning bush, and I haven’t seen a burning bush before, but I’ve seen a few burning leaves, you know? And that’s kind of how I envision God working in your life; you don’t always really know when He’s touched you. So that one’s about a guy running into Jesus on a bus ride.

Kinda sneakin’ in there.

Yeah, exactly. We didn’t change that song at all from his version, it’s just a great representation.

Waylon Payne’s definitely a guy who ought to be better known than he is.

For sure. I also got to do a classic Warren Haynes song with Monte Montgomery; we did “Soulshine.” When we were designing the record as quickly as we did it we thought, let’s bring in as many of these Austin cats as we can to come and do some of this stuff, and a few guys who were on the big scene, and I think we accomplished all the goals we set in that way. And so Monte came in and played guitar and sang on “Soulshine.” He’s a guy that, we’ve not toured together but we’ve done a bunch of shows, and I’ve always just been in awe of his talent ever since I first laid eyes on him. His mom is big in the Luckenbach world, and that’s where my wife and I got married, so there was a lot of connection in there for me and Monte.

Jack Ingram was the guy who introduced me to Todd Snider, and Jack’s one of my dearest friends on the planet, so when this project came up I called Jack up to come do a Todd song, so we did “I Am Too.” There’s also Lyle Lovett’s “If I Had a Boat,” which is the one I did with Cory. Tom Petty’s “Even The Losers” is one that I did solo. Ed Roland from Collective Soul came in, too. I met Ed at a charity deal we did together in Augusta, Ga., and I knew he wasn’t on a label at the time, and I asked him if I were to cut Collective Soul’s “The World I Know,” would he come and sing it with me, and he agreed, so that one’s on there, and it came out really great. There’s a Walt Wilkins song, too, “If It Weren’t For You” — that was really, really beautiful. Makes my wife cry.

Walt is a guy that I find really intriguing. He always has really interesting stuff to say. I know the two of you go back a ways. Tell me about you and Walt.

Walt was a friend of my brother’s back in the late ’80s when I was still in high school; they had met at church and become buddies. And I would come down to Austin to visit Dave from time to time and we’d go to church, so that was where I first got to hear Walt sing. Walt shortly after moved to Nashville to work as a professional songwriter, around 1990 I guess. And one of the first songs he wrote was “Songs About Texas,” and when I heard that song I just fell in love with it. This is when I was first learning to play, so I learned to play and sing that one. And then it wasn’t too long before my first two records and the first live records were out, so it’s time to do another record, and I wanted to write with Walt; you know, I wanted it to be a professional co-write, as opposed to just writing songs with buddies in the middle of the night. I wanted to write with someone who had been actually writing songs for professionals. So I contacted Walt through my brother, and we got together at his house in Nashville, and we wrote “Carry On.”

So, that was our first effort together, and it sure was an awesome outcome. That’s still a song that I love to play, right up there with “Wave On Wave.” You know, every night, one’s the first song and the other’s the last song. And a couple of years later, we’re doing bigger tours and stuff and Walt joined my band on acoustic guitar and harmony vocals, and he was in the band for about three years. We had a great time and did a lot of big shows, but he and Tina had a baby, and you know, he needed to go be a daddy, and I totally got it. He’s way into family.

I saw Walt and Tina play at Hill’s Café the other day, and their son Luke was playing the drums on a guitar case and doing a pretty good job! Walt’s a great daddy.

He’s just a great guy. He’s got a beautiful soul and I’ve got the utmost respect for him. We have similar tempers, too: When it comes out, it comes all the way out! He’s a dear friend. We hadn’t written together in years and years, but we finally got back together last year and wrote again, for this new record we’re gonna record. We wrote two songs, and one of ’em for sure will make it on there. I’m glad to have Walt back on my scene.

Speaking of that new record — I was under the impression that at least some of it had already been recorded. How far along is it, and what’s the Pat Green plan moving forward?

Well, we’ve demoed most of it, so in a sense it’s been recorded. Personally I think we might end up keeping some of the demos, because they came out so good. We’ll probably get going on it in March. As far as a plan, I’ve always been a strong believer in fate. You know, watching things unfold … it’s not that we don’t have a plan, but I do believe in an element of chance in things. About a year ago, I signed up with (manager) Enzo DiVincenzo, who also handles Stoney LaRue and the Randy Rogers Band and a bunch of others. I wanted to be with a stable of folks considered Texas music artists, because Texas is the backbone for me, the majority of my business is here at home. And even though Enzo offices in Nashville — because whether you like it or not, that’s where the music business lives, Nashville, L.A. or New York — nobody understands Texas music like Enzo does, so that’s why I’m with him. I wasn’t interested at all in a record label that wanted to be hands-on in the studio; I wanted to be with a label that would let me do what I want and let the chips fall where they may, and Sugar Hill/Vanguard having that faith in me was a huge bit of vindication for me. They’ve always been the tastiest, classiest label out there, with Alison Krauss, Robert Earl, Merle Haggard, Dolly Parton, Nickel Creek … to be in a corner with those guys is very exciting for me.

So lots of cool stuff going on and coming up. Anything else to cover?

Well … I hate to hear the negative talk regarding Cory and the new project.

I think what gets people talking at all about any of it is the level of importance that that first record has with the hardcore Texas music fans, and the fact that some of them can’t get over the obvious difference between it and the new one.

Well, don’t you think it should be different? I think there should be an obvious difference. I mean, it’s really hard to create, to me, a sequel to something that is that niche-oriented. To me you have to make an effort to make it different, or else, as I was telling Cory, if we did it exactly the same way, the complaint would be that it’s same-old-same-old. I just don’t understand people who feel they need to say negative stuff. I’m just a happy guy and I just don’t sit around and think about the negative. But, it does bother me.

I’ve tried to follow Willie Nelson’s lead. Willie’s never been worried about what someone might say about him … singing a No. 1 song with Toby Keith, for example. However, if I did that, people would gripe. But you know, if it went to No. 1, I would not give a shit.

[Laughs] Well, for what it’s worth, 99-percent of people don’t care about any of this other information. As long as the music’s good and you feel good about it, it doesn’t matter what anyone says, anyway.

True, that. Willie records with anyone he wants. It’s all about the music, and that’s the way I see it, too.

No Comment