By Thomas D. Mooney

Reidsville, North Carolina has always been there. The small, rural hometown of singer-songwriter BJ Barham has often lingered in the background, serving as a stark contrast for the bustling Raleigh that Barham and the rest of American Aquarium laid claim to in their early 20s. With every American Aquarium album, Barham went off exploring the vices of the road and big city. Over their six album catalog, Barham’s enthusiasm for road life and bad decisions was a rollercoaster. It swayed from the rush of establishing a band and playing night in and night out to resenting the never-ending highway to second-guessing themselves, and ultimately, rediscovering why they started in the first place. But all the while, for Barham, Reidsville represented a place to escape from.

In November of 2015, while the band was on a European tour, a series of terrorist attacks claimed the lives of more than 100 in Paris, France. With friends and family contacting Barham and company, an overwhelming rush of emotions flooded Barham. That was when he wrote the majority of Rockingham, his first solo album — aptly named after the county in which Reidsville is located in.

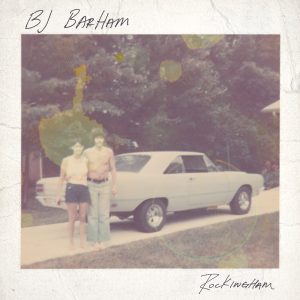

Rockingham (out Aug. 19) finds the songwriter going home and capturing the essence of small town life. While the vast majority of American Aquarium songs have always been autobiographical in nature, Rockingham’s charm is Barham’s bare bones storytelling while walking in other people’s shoes. Like its’ album and single covers, Barham’s Rockingham is a series of snapshots. The characters within its’ eight tracks are composite sketches of those close to Barham.

Rockingham (out Aug. 19) finds the songwriter going home and capturing the essence of small town life. While the vast majority of American Aquarium songs have always been autobiographical in nature, Rockingham’s charm is Barham’s bare bones storytelling while walking in other people’s shoes. Like its’ album and single covers, Barham’s Rockingham is a series of snapshots. The characters within its’ eight tracks are composite sketches of those close to Barham.

“It’s a stripped-down record about small town life,” says Barham. “I think those kind of records resonate with people because there’s way more small town people.”

Highlights such as “Unfortunate Kind” find Barham tackling heavy subject matters like he’s never done before. Like Jason Isbell’s “Elephant,” and John Fullbright’s “The High Road,” the song combines the raw emotions of losing someone close. In this case, the protagonist loses his wife of 39 years to dementia and sees them slowly fading away. Barham’s straightforward storytelling cuts to the bone in the simplest, but most effective of ways. The title track, “Rockingham,” is as close as Barham ventures towards the anthemic choruses American Aquarium is known for. Still, the simple acoustic guitar strumming, banjo plucking, and harmonica yelps feel comfortable, worn in, and warm.

Like Bruce Springsteen’s New Jersey, Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl, and Isbell’s Alabama, Barham too finds his muse in his home state. They’re all determined to write about the good, the bad, the ugly, and mundane of their home towns. Barham’s Rockingham does just that.

You were over in Europe when the Paris attacks happened. It was then when you wrote the bulk of Rockingham. That doesn’t really seep into the content of the album, but all of the people back home contacting you guys really gave you a reason to start writing.

Yeah. It’s one of those things. You never know where songs are going to come from. You can be inspired by the music you hear, the books that you’re reading, the things you’re seeing in the news. Like last night, I was on a run, saw something, and an idea popped in my head. It’s about allowing yourself to be open. It’s almost like a trap. If you leave that trap open long enough, you’re going to catch something. The problem is, if you leave a trap open and walk away, it can escape. But if you’re open, the muse hands out stuff every single day. I’m not really a religious person, but songwriting is something very spiritual for me — it’s a higher thing. After the attacks, there was an overwhelming amount of emotions. Not only are you worried about you being in an American band in Europe right then, but you’re also getting the text messages and phone calls from your parents and family. You realize a lot of people care about you and keep up with what you’re doing. Then you start thinking about things like if you’ve ever told your great aunt that you loved her and things of that nature. A lot of different emotions come through. Luckily, we had a couple days off and I jus sat in a room writing songs.

You wrote most of those in two days. Is that the most you’ve ever written in a 48 hour period?

A record has come out in two days. That’s never happened for me before. The most I’d ever written before was a couple songs in a week. This was one of those situations where entire songs were falling out one after another.

With American Aquarium, you’ve always been a pretty straightforward writer. With Rockingham, you’re somehow even more so. Getting these songs out so quickly, do you think that helped contribute to how direct and raw the album is?

100 percent. There’s no questioning on what I’m writing about. It’s to the bone. This litter of songs — I’ve referred to them as a litter a few times now — they came out so close together and with the same mindset, it was easy for me know it was going to be a record. Whether or not they’re different offshoots of those emotions, you can tell they all came from the same place. I added a couple of old American Aquarium songs to the mix to round out the record. It was for selfish reasons. The songs added, they’re songs American Aquarium doesn’t ever play. They’re songs that I personally think are good. They matched up perfectly with the others and now when I’m playing solo, it gives me an excuse to play them every night.

I’ve always wanted to do a solo record — and you can really see it on every record we’ve done. Any slow song on an American Aquarium record was the start of a solo record. I’d just abandon it so we could get another band record done. If you go back, Dances For the Lonely is “Betting Man” and “Tennessee.” Small Town Hymns is “Reidsville” and “Water in the Well.” Fast forward to Burn.Flicker.Die and it’s “Harmless Sparks” and “Northern Lights.” Songs like those, they became great band songs, but they were all the start of a solo record that never happened. This was the first time where so much poured out at once where I didn’t have to wait. The whole process went by so quickly. I wrote them in November. I wanted to record them in December, but Brad Cook, who produced the album, told me to wait. He told me to sit on them and refine them. We put together a band and the first week of February, we recorded. I met the band Monday. We rehearsed Tuesday and Wednesday. Thursday and Friday we recorded the record. Saturday, we mixed it. Sunday, we mastered it.

“I’ve always wanted to do a solo record — and you can really see it on every record we’ve done,” says BJ Barham. “Any slow song on an American Aquarium record was the start of a solo record.” (Photo by Alyssa Gafkjen)

You mentioned before how the album basically doesn’t have one plugged in instrument. It’s really a folk album in that sense.

Yeah. I think there’s a couple of pedal steel parts that are technically plugged in, but for the most part, it’s unplugged dobros, acoustic guitars, banjos, accordions, organs, and pianos. I wanted to be able to perform this record in someone’s living room or in a giant theater. I wanted it to feel real. There’s a lot of studio tricks out there. We’ve never been about studio tricks.

You’ve always been a first-person storyteller. Your songs, they’ve always had that autobiographical sense to them. These songs, you’ve stepped away from that and done other people’s stories. Have you been a little apprehensive to go down that road?

For sure. I didn’t know how — obviously, I do — but I don’t think I had the confidence to. This was very much so an exercise in fictional narrative. I always joke about how with American Aquarium, we put out a record and it’s almost like a yearbook of what I’ve done over those two years. You can almost watch the band go from the partying and womanizing band into the questioning why we’re doing this band and now finding success and pushing through. You can see that arc through the albums. It’s watching the rise and fall. It’s watching someone in their 20s being completely irresponsible, having to answer for their mistakes, and then finding a new reason. For me, that was getting married and getting sober. It’s finding this new way to express myself. American Aquarium has always been that outlet for me. So this solo record, it’s for me to make stories up. You’d think it’d be the complete opposite. [Laughs].

When I say fictional narrative, these characters are very real. They’re amalgamations of people I’ve met. One may be five people who I went to high school with. It’s just cooler as one character. A lot of these lines, they’re very real to me. Like the line in “Unfortunate Kind” about the wife burning the pecan pie the first week they got married, that’s a story my mom continuously tells — except with my mom, it was turnips. My dad loves turnips. Not turnip greens. Turnips. The root vegetable mashed up, add butter and salt. My dad loves them. My parents, they did it old school. They didn’t live together before they got married. The first week they were married, my mother called my grandmother asking what my dad’s favorite meal was. My mom apparently made the most horrendous dish of turnips. My mom could see my dad didn’t like it and it devastated her, but my dad, he asked for seconds and thirds. [Laughs] I always loved that story. 39 years, that’s how long my parents were married when I wrote the song, too. I plucked different pieces of my life and put them into these fictional narratives. They feel lived in.

That song, “Unfortunate Kind,” it feels so genuine and real. It feels so personal — like it was about your grandparents or something.

You know, when I got done with it, I played it for my wife and she just started bawling. I knew I was on to something then. I’ve never had anyone close affected by dementia or Alzheimer’s. It was really interesting to write the song solely based on how I’ve seen it effect others. People think love can be forever. That it can be impenetrable. But it’s not. Time comes around and defeats everything.

You’ve always written with nods to blue collar people. They’ve been details in your songs. With Rockingham being more so about your hometown of Reidsville and the people there, you take that more head on.

I tried putting myself into those characters’ shoes. It’s the first time I’ve ever done it. There is no guide book. It was trying to put myself into their shoes and write about how they felt and what they did. “American Tobacco Company” is about my grandfather and “Rockingham” is about my dad. They didn’t lead glamorous lives. My grandfather worked 40-plus years at a tobacco warehouse. My dad sells auto parts and has since he was 18 years old. It’s thankless work. He’s raised two boys who aren’t in prison and who are educated. He wins. He’s better than 90 percent of the dads in my hometown. He didn’t necessarily see himself doing that, but he took responsibility head on. It blows my mind. I think that’s just as inspiring as anything others are writing about. There’s so many country artists writing about things they don’t know. Maybe the things I know are pretty boring, but I find really inspiring things within them. I find something truly special about the love my parents have for each other. I think that’s better than any cheesy love story.

How well do you think Rockingham represents Reidsville? Do you think you covered all aspects of growing up and living there?

I think I painted it in a solid way. It has its good and its bad. It’s a small, rural farming town in the Piedmont region. Couple thousand people live there. Reidsville is a thousand other small towns in America. Very conservative — not necessarily in a bad way either. They just don’t like change. It’s the last place that change comes. Raleigh, there’s a lot more culture, art, and music. I’m playing the big fall festival there this year. Usually, they get a B-level country star. There’s a farmer’s market they shut down with a 2,000-person amphitheater. This year, I’m the headliner. “BJ Barham, the hometown boy done good” kind of thing. That’s kind of cool. A bunch of my family works for the local county government. It was all on the e-mail blasts about how the record was about Reidsville. It was really nice to see my hometown get really excited about a record.

No Comment