By Lynne Margolis

(Aug/Sept 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 4)

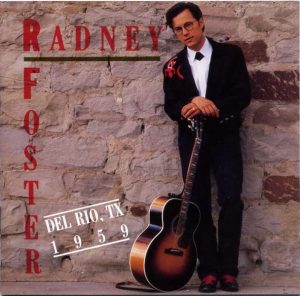

When Radney Foster posed for the photo gracing the cover of his first solo album, Del Rio, Texas 1959, he was a hot young Nashville act looking cool in a short-waisted, lizard-embroidered jacket, white button-down shirt and black jeans, his dark hair combed back and his hands resting on the headstock of a beautiful acoustic guitar. Leaning against a stone wall, he peered earnestly at the camera through round-rimmed specs.

When Radney Foster posed for the photo gracing the cover of his first solo album, Del Rio, Texas 1959, he was a hot young Nashville act looking cool in a short-waisted, lizard-embroidered jacket, white button-down shirt and black jeans, his dark hair combed back and his hands resting on the headstock of a beautiful acoustic guitar. Leaning against a stone wall, he peered earnestly at the camera through round-rimmed specs.

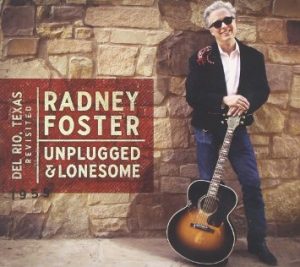

Twenty years later, in his latest cover photo, his hair is gray, but still thick. Leaning against a similar wall, he’s wearing the same jacket and holding that same, now-weathered Gibson. But sunglasses — and a big smile — have replaced the wire rims and serious look. His v-shaped continental tie is gone, his collar’s unbuttoned and he seems much more relaxed. One might say the same about the album on which this photo appears — Del Rio, Texas Revisited: Unplugged & Lonesome.

Twenty years later, in his latest cover photo, his hair is gray, but still thick. Leaning against a similar wall, he’s wearing the same jacket and holding that same, now-weathered Gibson. But sunglasses — and a big smile — have replaced the wire rims and serious look. His v-shaped continental tie is gone, his collar’s unbuttoned and he seems much more relaxed. One might say the same about the album on which this photo appears — Del Rio, Texas Revisited: Unplugged & Lonesome.

Though the Arista-issued original yielded four top-40 hits on Billboard magazine’s Country Singles chart — “Nobody Wins” reached No. 2 and “Just Call Me Lonesome” made No. 10 — Sony, which took over Arista parent BMG, couldn’t be persuaded to reissue the out-of-print disc. It finally agreed to do so in digital form, but Foster’s fans, who still request Del Rio songs every time he performs, had been seeking something more tangible.

So he decided to record the album all over again. It’s an increasingly common move among artists in the same boat. But Foster wasn’t about to deliver a “hacked” (his word) version of his past glory; most redos, he says, pale in comparison to the originals.

“So I just thought, ‘Let’s do it unplugged,’” he explains. “‘Let’s do something totally different with it.’

“It was a really big record for me,” Foster continues, his speech carrying only slight traces of his Southwest Texas roots under light Tennessee seasoning. For one thing, Del Rio proved he had an ear for more traditional country than he had created in his previous incarnation as half of the pop-infused duo Foster & Lloyd.

“As a songwriter, I think it set me on a path that I still travel today,” he adds. “Even though that was a mainstream country record, they gave me the freedom to have songs on there like ‘Old Silver’ or ‘Went For a Ride’ or ‘Hammer and Nails’ that were outside the norm of what one would think of as mainstream country.

“I mean, a 4½-minute Irish murder ballad is not gonna make it on country radio,” he notes, laughing. “Even to this day, young artists come up to me and say how big an influence that was on ’em. So I thought, ‘Well, let me go revisit this thing and think of it in a completely different manner.’”

Foster’s discussing the project via phone from his Nashville home, but in March, he spent an almost feverishly paced few days in Austin, laying tracks at the rustically elegant Cedar Creek Recording with producer Justin Tocket.

In the studio with him were original Del Rio producer Steve Fishell on dobro and Weissenborn; Dixie Chick Martie Maguire on fiddle and backing vocals; Jon Randall Stewart on guitar, mandolin and backing vocals; Michael Ramos on accordion and Wurlitzer organ; Matt Borer on percussion; and Glenn Fukunaga on bass. Fiddler Brady Black, of the Randy Rogers Band, also contributed. And they were, literally, in the studio with Foster, recording live. No one wore headphones; they played a song through and if they needed to, they did it again. With the level of musicianship involved, it went as smoothly as they thought it would.

In the studio: Steve Fishell, Mallory Warman, Radney Foster, and Martie Maguire.

(Photo by Lynne Margolis)

The live vibe

With candles glowing in the cutting room and natural light filling the control room, the rough-hewn wood and stone studio carried a casual ambiance during the sessions. A large dog wandered in and out of the lounge, where wholesome snacks filled a table and a TV played silently. Instead of studio pale, the players all appeared fit and healthy — and focused, despite an audience of fans and aspiring artists or producers who paid several hundred dollars apiece for the privilege of watching the proceedings as students of Fishell’s Music Producers Institute. The arrangement not only helped to finance the album, it also provided a live audience to give the proceedings even more immediacy — which was the intent behind recording it live in the first place.

“There’s nothing like having an audience of people there in front of you to make you really dig in hard,” Foster says. “I wanted that sense of aliveness. I knew I was getting great enough players that getting great performances wasn’t gonna be a problem.”

As for the decision to record without headphones, he explains, “In a headphone world, everyone’s separated, and it’s actually, for a singer, harder to hear pitch. And there’s something sort of magical when you get everyone playing in a circle in a room. There’s a kinetic energy that just happens; you don’t have that feeling of separation. There’s a bit of a feeling like you’re in a fishbowl whenever everyone’s in their own little clinical booths with headphones on. Recording with everyone, you have fewer options, because the recording is what it is. You can’t go back and fix it.”

Maguire concurs.

“I actually prefer it now,” she says. “It’s hard to do, but when you’re the last one to overdub and you’re in there by yourself, you just feel like the magic is over and you’re having to re-create it — and drink a lot of caffeine.”

In a group session, she says, “There’s something about the energy in the room; everybody’s kind of on edge. It’s like a live performance on a stage. You get one shot and you gotta be on your toes.

“It’s way more fun,” she adds. “And you end up playing off each other more, and I think the music benefits from that.”

The sessions almost had the feel of a house concert — except for all the recording gear, the glass windows separating artists from audience, and discussions about how or when someone should play. (At one point, Ramos was instructed “to sound as Flaco-esque as possible” on an accordion part for “Just Call Me Lonesome.” Otherwise, he was reminded, “the earth might fall farther off its axis.”)

Of course, he nailed the Bakersfield-influenced track — which, interestingly, had no fiddle in its first incarnation. Maguire, who says she listened to the album on cassette till she wore it out, later admitted she was surprised when Foster pointed out fiddle is a distinctive element of the Bakersfield sound.

“I’ve learned something,” she said afterward. She also admits feeling somewhat intimidated when Foster invited her to contribute, which he did during a February benefit Maguire’s other band, the Courtyard Hounds, played for a scholarship established in his late father’s honor. “I was very, very honored,” she says, “because I don’t think of myself as a studio player.”

But she already had a comfort level with some of the musicians; Fishell had produced some early Dixie Chicks albums, and Maguire grew up playing the bluegrass festival circuit with Randall. “It’s kind of like old-home week,” she observes. The Chicks also have recorded several of Foster’s songs, and his request for her participation led to a daylong, three-song writing session at her Austin studio.

“I’m hoping this is going to be the start of a songwriting relationship as well,” Maguire adds.

Updating the past

Asked why Fishell didn’t handle production this time out, Foster explains, “I didn’t want Steve and I to overthink it … I thought that maybe we might be too married to the original arrangements.

“The other thing is that Justin is such a great engineer sonically, I knew that was gonna make a big difference in how we did things. He really helped me think through how to do it completely without headphones, everyone in the same room.”

Tocket also had significant input regarding song arrangements.

“He was just really adamant that ‘A Fine Line’ get slowed down and not have any background vocals on it,” Foster notes. “He said the desperate nature of the lyric got lost in the big, sort of Springsteen rockerness of that original track. And he was right. He made a lot of great calls. He was the one who said ‘Louisiana Blue’ ought to have washboard on it. His wife’s from Lafayette; he’s spent a bunch of time down there, and … wanted to bring that entire influence to that song, which was really kind of cool.”

Unplugged & Lonesome differs from the original Del Rio in other ways as well. The song order has been switched somewhat; “Old Silver” is now the seventh track and “Went For A Ride” is now the final track. Which makes it No. 11, because Foster also added a new song, “Me and John R,” co-written by Stewart and Darden Smith.

“You always want to add some little lagniappe to things, you know, give the fans something extra,” Foster says of the decision. The song was carefully chosen to fit “the voice” of the original album as well as the updated version’s acoustic vibe.

Unlike when the remaining Beatles de-Spectored Let It Be and released it as Let It Be … Naked, it’s unlikely controversy will surround Foster’s revisitation. Fans of the original are likely to be thrilled with this new treatment; the songs are timeless, yet carry a new immediacy and warmth that’s completely attributable to the acoustic instrumentation and recording method. Some overdubs were added, such as Marc Broussard’s backing vocals on “Louisiana Blue,” Jack Ingram’s on “Hammer and Nails,” Dan Baird’s on “Don’t Say Goodbye” and Georgia Middleman’s on “Went for A Ride,” but just as Foster’s cover image is more relaxed, so is the music.

“It could have been a disaster,” Foster says, laughing. “And it wasn’t. It came up as a plum. And it was really, really fun to do. I think the excitement and the fun we were havin’ showed up in the music itself. And that’s what you want. That’s what you want every time.”

No Comment