By Holly Gleason

(LSM July/Aug 2014/vol 7 – issue 4)

“That’s not anywhere in the So You Want to Be a Country Singer Handbook,” Miranda Lambert says, explaining the vertigo of sudden fame. Or more specifically, the kind of super fame that results when one very famous person marries another very famous person, a la Lambert and her husband, fellow country star and The Voice coach Blake Shelton. “It’s gone from being one thing — being people with songs on the radio, out on the road — to a whole other kind of interest.”

Of course, Lambert, 30, has long been a fascinator to the media and country music fans for her straight-talking, keep-walking, anti- Barbie sort of girly-yet-hardcore grrrl power. This is the firebrand Texan who once walked out of a session as a teenager because “it was too pop”; whose early songs like “Kerosene,” “Gunpowder & Lead,” and “Crazy Ex- Girlfriend” made her a RIAA-certified platinum blonde long before the chart-toppers started happening. But there’s a difference between being on the radar and literally blowing up the radar. And Lambert, once a feisty li’l thing who could draw a bit of attention for her art and attitude, has become a tabloid mainstay. For her marriage. For her weight. For her haircuts, her clothes, and heavens knows.

“Her celebrity right now is enormous,” affirms Cynthia Sanz, assistant managing editor of People magazine. “Ever since she and Blake got married, it’s been a supernova. People like them, and want to know more about them — all the time. That (kind of) fame thing can be very scary, and she can’t get away from it. That’s the reality. When she says anything, it’s going to be everywhere. Little things you thought meant nothing. And sometimes people interpreting it to fit their story instead of your intention …

“It can’t be easy seeing your life on the cover of tabloids every other week,” Sanz continues. “To let that roll of your back, you have to take a long look at yourself.”

It’s a long way from just being the daughter of two private investigators who just wanted to write gritty songs that matter. “It’s a lot like I expected,” Lambert admits of the full-force blast of a TMZ reality. “But the thing that surprises me the most is how fast the change happens.”

That new state of visibility is what no doubt drew her to “Priscilla,” from Platinum, her new album. Containing the lines “Golden gate, we had to put up a gate/to find time to procreate/or at least that’s what we read …,” the song reflects how jarring the media frenzy can be. Still, the learning curve hasn’t been as bumpy for this woman with a license to carry as you’d think.

“I realize at certain moments when people get in your face, and they’re looking for a reaction, I have to laugh it off,” Lambert offers. “What else? So you do. And you can be bugged, or you can realize you get to live your dream, too.”

Lambert is calling from the beauty shop chair in the cramped make-up room at The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, where she is in the midst of the usual big-star promotional tromp to set up her new album, set for release the next day. “This one isn’t too bad,” she says of the current publicity blitz. “But tomorrow is the 4:30 call (for Good Morning America) — that’s the one you dread all year.”

She’s not really tired, though; certainly not in the way you’d think someone who’s been chasing the dream with a major-label deal would be after nine years. If anything, she sounds almost charged — and with good reason. Platinum is Lambert’s fifth album, and its success is assured. The lead single, “Automatic,” which she’ll perform on Fallon later, is already in the country Top 5, and coming after “When We Were Us,” a No. 1 duet with Keith Urban, and heading into “Somethin’ Bad” with Carrie Underwood, both Lambert and the album have momentum in their favor. To wit: Platinum will debut at No. 1 on both the Billboard Top Country Albums chart and the magazine’s all-genre Top 200.

But right now, at least, in the last few hours before the album’s release, Lambert does have a hint of anxiety. Because beyond fame and sales figures, she still cares first and foremost about the music itself. Knowing this is the final push to deliver the baby, she continues, “It’s weird. I recorded this record in August, and it’s just now coming out. I’m ready for (Platinum) to be here, to know what they think of the record. It’s been building up and building up … I want some feedback! I want some people to hear it. I’m anxious, not in a bad way, but in a wanting to share it way — and that builds up. You wanna know.”

* * *

Musically, Platinum is a wild ride. Beyond ruing the lost way of doing things in “Automatic,” which has the same innocence as her very award-winning “The House That Built Me,” Lambert opens with the hard-to-hold truth of “Girls”; goes for a churning big-top put-down with “Two Rings Short”; snarls across the raucous cacophony of “Little Red Wagon”; Western swings with the Time Jumpers on “All That’s Left”; truculently winks ’n’ nudges through the coming-of-age (and saggage) admission “Gravity Is A Bitch”; and twangily homages junk-shop treasures in “Old Shit.” There’s also a late-70s Texas dancefloor lament, “Hard Staying Sober,” the laconic-yet-sultry country blues of “Holding Onto You,” and even a John Prine-evoking number, “Babies Making Babies,” that looks at teenage re-population without judgment, perhaps even kindness.

It’s a lot of songs and a lot of flavors. Still, it’s the sassily brazen “Platinum” and the pensive “Bathroom Sink” that stand out as the album’s two most defining tracks. Shamelessly embracing all of her worldly knowledge, physical attributes and sense of humor, the title track offers a game plan to all girls who aspire to make their way in the world, while “Bathroom Sink” — written by Lambert alone — is a raw moment of reckoning with the doubts and falters all women face.

“The one thing I can say about Miranda,” Frank Liddell, the producer she wanted to work with — and has — since her stint on Nashville Star, says, “is that every record she’s ever made is reflective of exactly where she is in her life at that moment. She is real and honest about her life, and you can hear it.

“She was married for one week when we started the last record,” he continues, referring to 2011’s Four the Record. “Literally — got married, went on a honeymoon and started on a record. You can hear that newness on it. Now she’s a celebrity; the microscope is always on her, and there’s a lot to deal with. But what’s even more interesting is, she’s still that girl from Lindale, Texas — now obviously a celebrity, but she hasn’t forgotten that. And all the songs on this record reflect that.”

Or, as Radney Foster, a celebrated Texas songwriter, says of the frisson between small-town girl and high-watt celebrity, “Not everybody’s married to a great big superstar, but I promise you there’s still plenty of petty jealousy at the country club in Tyler, Texas, the church group in Amarillo, or the PTA in Nacogdoches. So, there are lots of ways to relate to these songs.”

“When I was getting ready to start making this record,” Lambert says, “I did a little inventory: going back to Kerosene, listening to all the songs and all the things I’d said. I know I’ve changed a lot, but I have this common thread that runs through everything. It’s a female empowerment thread, no matter where you are in life; but also, there’s a vulnerability. I’ve always been honest in my music. I’d rather be honest even if it’s hurtful, because to start there, you can tell the truth. Because I don’t have a lot of fake in me, its just not an option — and it takes strength to be willing to say those things that are uncomfortable to say. You don’t know how it will be received, but you still have to suck it up and do it.”

“Bathroom Sink” unflinchingly captures that jagged edge of the truth. It’s about a woman staring down her reflection, the make-up mask that creates an illusion gone and the flaws only she can see revealed — along with the fractured reality of pressure, expectation, and the feeling of not quite ever being enough to go around. The song serves up hard truth about the way so many women treat themselves, and yet it is also unquestionably one of the most personal songs Lambert has ever shared on record.

“Everything in the song, that all came from me,” Lambert says quietly. “I’d just had an argument with my mom, and it’s all the things you want to say, the things you feel … and looking in the mirror, it just adds up.

“I was getting on a flight when it happened, so I wrote it in my phone. Then when I got to the bus, I picked up my guitar and went straight to the back. The idea my mom’s gonna be hurt was hard, but you know that’s what happened. Because you look in the mirror and see yourself without the make-up, you can’t hide. All the make-up and hairspray in the world may hide what’s underneath from people, but it’s still there. So how are you going to handle it? What are you going to say?

“Music is a way to make an excuse for yourself,” she explains. “You can get it all out when you’re writing: put it all down, be confrontational, because it’s a song.”

“She’s remarkably honest on this new record,” says Sanz, a fellow Texas woman who was born in San Antonio and graduated from the University of Texas’ journalism program. “The looking in the bathroom and seeing all that? Every woman does it, pretty much. Writing a song about it, let alone just admitting it? That’s what makes her who she is. And it’s interesting, because with her it is who she is as an artist as much as anything. In some cases, the music is second to the celebrity. But not with her. She’s always challenging herself. She puts out a record and it does well, and some people would do that [same thing] again — but she follows her heart.”

* * *

You’d think winning three consecutive Academy of Country Music Top Country Album Awards for Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Revolution, and Four the Record — as well as Revolution’s “The House That Built Me” and Four’s “Over You” winning almost every song and/or single award out there — would be pressure enough for an artist going into her next record. But this time around, the glare of Lambert’s celebrity was also in the studio. If the songs on Platinum are musically more diverse, perhaps a bit more grown-up, they are also informed by the sense of knowing that this time around, more so than ever before, people are really watching and listening.

“The interesting thing about this record is, we used pretty much the same cast of characters,” Liddell recounts. “I asked her if she wanted to use the same players, and she said, ‘Yes.’ It’s always throwing caution to the wind, and these guys understand that.

But you could feel it: everybody showed up not quite knowing what to expect. To do things different for different’s sake is never good. We’ve never done that with her. But the tracking this time, everyone felt more pressure than we ever had. The success was in the back of everybody’s minds.

“Every time she’s getting ready to make a record, she gets a little panicky,” the producer continues. “And I get that, too. You know, you can talk about it all you want, but then you have to put up. That’s the deal. I think the elephant in the living room really pushed us.”

Lambert’s albums have never been by- the-books Music Row propositions. Her lyrical attack is edgy, and the playing has always reflected that. But on Platinum, the stakes raised. Guitars really do lacerate, the beats hit hard; in a world of “you throw good for a girl,” Lambert’s record has the same velocity as Eric Church or Jason Aldean.

“Miranda’s always pushed buttons,” Liddell explains. “But you don’t just push ’em for the sake of it. Over the years, she’s pushed so many, so then where do you go? There’s more to (the way she looks at her music) than just ‘You can’t say that? Watch me …’ or ‘You can’t play that on a country record? I can!’

“In some ways, the pushing is in the approach. I think it’s the most musical record she’s even made.”

Sanz, who’s tracked Lambert’s career for People since the beginning, concurs. “She came out guns blazing, all the time. It was her thing. She’s mellowed a little. She’s 30, and she’s a superstar. Now, you know there’s a reason when she reaches for her gun.”

There’s also the influence of the Pistol Annies, Lambert’s all-girl trio with songwriter/ artists Ashley Monroe and Angaleena Presley. Like a sorority with songs, the three have great fun — but also push each other’s boundaries. Though Lambert’s success far eclipses that of her friends, there is no diva at the center in their dynamic. If anything, the Annies, whose Hell on Heels and Annie Up have been critically lauded and Country Album Chart-topping, provide an opportunity to take things even farther. Whether it’s the (al)luring “Hell on Heels,” the joyously hard-living “Taking Pills,” or the lament of “The Hunter’s Wife,” there’s a glimmer of humor beneath the audaciousness. Full-tilt to the extreme, the Annies land the truth in their confessions of wild living, gold- digging, small-town hypocrisy and the plight of a wife forgotten with a glimmer in their dark- kohled eyes.

“It was so much fun,” Lambert enthuses about the Pistol Annies. “Like a slumber party but more fun, because of the music … and it was so different from being a girl singer onstage with an all-guy band. Instead, it was a bunch of girls out making music and having fun, and sorta …”

Lambert doesn’t pause, but the gear shift in the answer is evident. “It gets a lot riskier because you’re not up there alone; you’ve got someone else up there saying it, too. It made me a little more comfortable, broadened my horizons. And all the things people say didn’t matter — the ‘it’s too country, it’s too rock ’n’ roll, too punk, too Texas,’ whatever … We let the lyrics speak ‘cause that’s the leveler in the end: What does the song say?”

Radney Foster recognized that quality in Lambert when he wrote with the 19-year-old fresh from Nashville Star. He was struck by her intent and her focus, as well as her charisma.

“She had all the goods,” he enthuses. “She sang like an angel; God reached down and gave her a thunderbolt for a voice. She had all that character, but she wasn’t trying to be recognizable, she just was.

“She figured out how edgy she wanted to be yet, or could be,” Foster continues. “She and Frank started experimenting, and our sweet bluegrass song didn’t fit. But even then, when we got together, all she wanted to do was write something very real. Miranda didn’t just want to write a hit song, that wasn’t the reason for her sitting down to write. Most modern country music is idealizing the world, creating some nostalgic vision, but that’s not real. But the world in Miranda’s songs — I know people who live there. When you step back and look at the real greats — Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Loretta — they were all real. Loretta Lynn is a singer-songwriter; she’s also a big country star, but it’s the writing. Same with Dolly Parton. I mean, you don’t get to ‘Jolene’ without being real.

“Miranda’s the same way,” he says.

Lambert notes that her candor, both in song and in person, isn’t always embraced or understood. “I think people take it the wrong way sometimes,” she admits. “It’s gotten me into trouble, saying things that I think.” But Sanz disagrees; in her professional opinion, Lambert’s refreshing frankness has only served to endear her to the public. As someone who gauges celebrity value for the nation’s top celebrity news weekly, Sanz’s job depends on assessing America’s hunger for different bold-faced commodities. And in a world of shock, gawk and gape, rare is the celeb wanted for something other than scandal, stupidity, or egregious excess.

“She’s certainly beautiful, but she says what she thinks … and people feel like they know her,” Sanz says. “When she talks, you get a sense of who she is, and what matters to her. She lives her life her way, and she doesn’t take crap from people. That’s not easy to do. She’s in a business where people want to shape her into something, and she has stayed true to herself. That courage … the ‘say what you think’ thing? There’s an old saying: ‘Texans are like tea bags. They do well in hot water.’ Miranda proves that all the time.”

Liddell concurs. “Miranda is unapolo- getically exactly who she is. When we cut ‘Baggage Claim,’ she said ‘shit.’ When it was a single, we had to edit it out … but there was never a question of whether to say it or not when we were recording. That’s not for effect, that’s just how she talks. That’s exactly what she’d say to someone whose crap she was over.”

* * *

If that’s what people notice, or have focused on, though, Lambert seems to land on the opposite polemic. For her it’s not the “oh, yeah” thrust of her songs that define her life, but more the “oh, wow …” moments. Making her way through a very complicated, very busy pair of careers — because Shelton and his career must always be factored in — there’s still a part of her amazed by the experiences she gets to have.

In “Holding On to You,” she sings of drinking with the Highwaymen and watching the Rolling Stones. In those moments, she is once again a 12-year-old girl gobsmacked by music. “There are moments where I go, ‘Am I really doing this right now?’” she confesses. “In those moments, it seems really unreal. Getting to perform with heroes like George Strait and Merle Haggard? Hanging out with Loretta Lynn and Sheryl Crow while making a video at (Loretta’s) house? I look and it’s like, ‘Wow … How did this happen?’”

She pauses, trying to measure it all. Finally she acknowledges the centrifugal force of her life, and how it has pinned her against those moments with such velocity from the next six things, it can be hard to fully embrace the experience.

“I’m learning to soak it all in,” she says. “The last 10 years, it was always trying to get to the next thing, next level, next milestone. ‘What’s next? What’s next?’ Because it does just keep coming at you, and you have to keep dealing with all of it. You can’t hit pause.” Marion Kraft, Lambert’s longtime manager, laughs thinking about the path, the alternative version of how one becomes a superstar without the standard radio hit/ radio hit/radio hit/tour paradigm. “Four years into her career, people were coming up and saying ‘Congratulations’ for her success. We didn’t get what they were talking about … We thought she was already successful ’cause she got to do what she loved! Years one and two, we thought we were successful once she had a little airplay and could go tour …

“You know, having more money and more hits, that’s not why she does it.”

Lambert, who knows she’s going to have to hang up soon, is thinking before she answers. The notion of that moment when everything changed is so cliché, and yet for some performers, there really is one moment when they realize what can be. And it’s not always winning that first Female Vocalist of the Year Award, or headlining a major tour or even earning that fourth platinum album.

Lambert understands, and she’s taking the question seriously. Because beyond the glam squads, red carpets, long bus hauls, true l-o-v-e with Blake, there is a truer, deeper reason why she does this.

“I see myself as a 12-year old girl at the George Strait Country Festival,” she says. “I thought he saw me, and I really believed it! George Strait saw me! That was so important. And I want my fans, when they come to the shows, to feel like that, too — the idea that I saw them.

“Parts of me are still that girl and parts of me are more world savvy,” she continues. “But I’m pretty much the same overall. Yes, I’m a little more business savvy than the little wide-eyed 12 year old, but that little girl is still the person I try to focus on. When you think about those fans, and you remember when you were just like them … those moments keep me in check! When I get tired, and maybe I’m not appreciating the little things, the reality of all of this, I think about what (country music and the stars) meant to me growing up, and I hang onto that.”

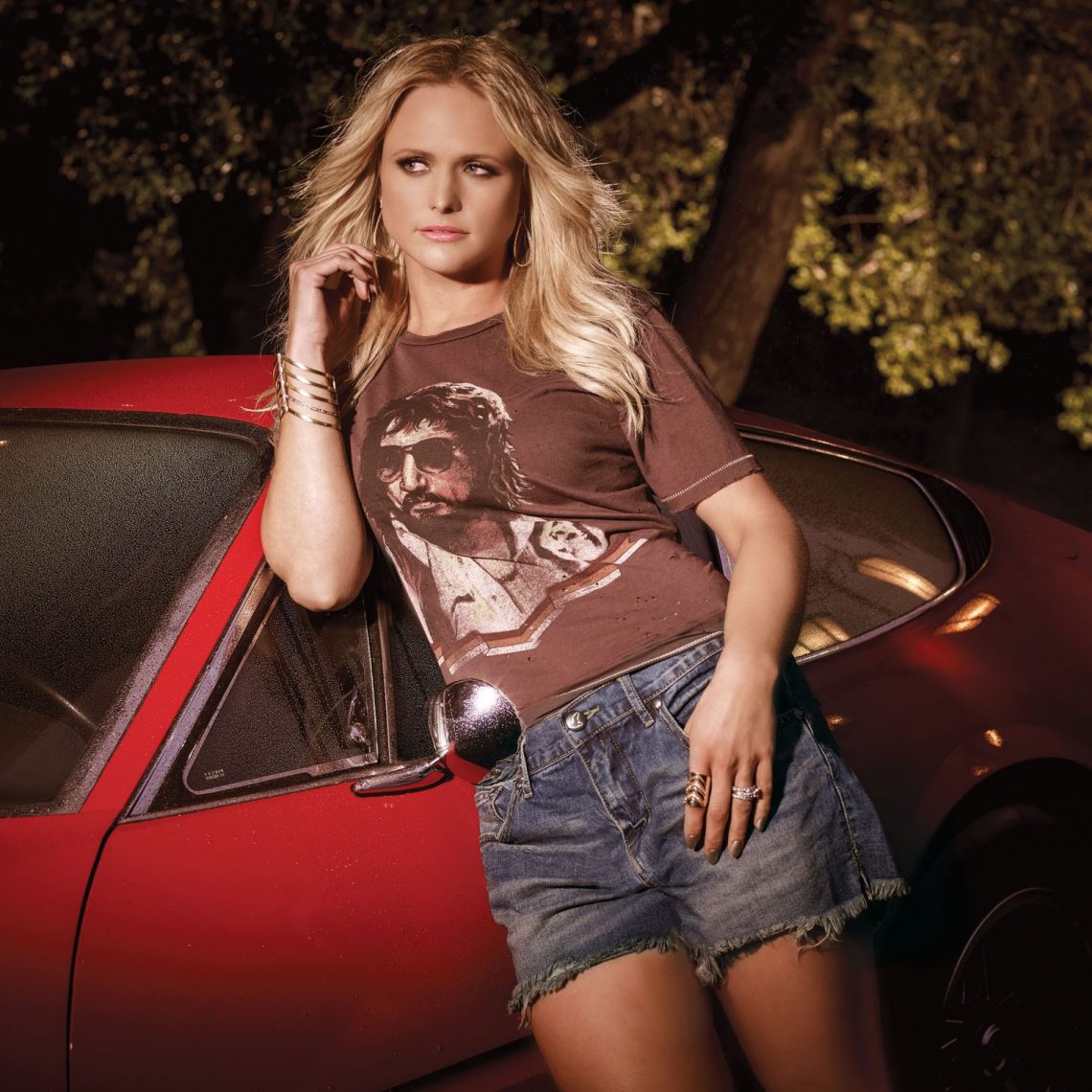

She’s a long way from the wheat-colored blonde with the two little braids hell-bent to sing, but Lambert doesn’t forget. She had a big dream, in some ways bigger than she knew — and she made it come true. With grit and determination, but also with a lot of pink, crossed pistols as a logo, big make-up and bigger hair and cut-offs, a don’t-mess- with-me attitude and infinite sweetness, she forged a whole new kind of country girl singer: brash and lovely, tart and sweet, redneck and sophisticated.

Lambert laughs when you point out the contradictions, reminds you all those things are her. She knows all those things are most women, too, and maybe that’s part of it. In a world of brokered femininity, where magazines tell girls who to be and how to measure up, Lambert doesn’t bother considering Madison Avenue’s take.

Thinking about all those 12-year-old girls and 20-something young ladies trying to sort it all out, even the 30- and 40-something women trying to make sense of what happened, she knows just what she’d tell ’em.

“Believe in who you are, and stick with it!” she says. “It’s gotten me through this life. It’s what keeps you from turning into someone you don’t now …

“You can be anything you want to be if you know who you are inside,” she insists. “My mama told me that growing up, and throughout all of this. Hang onto who you are, it’s the most important thing. And keep working.”

No Comment